Three years ago, the Covid-19 pandemic struck the United States, and the economy sputtered in the direction of collapse. Social distancing protocols caused businesses to shutter, and millions of Americans lost their jobs. Between February and April 2020, the unemployment rate doubled—then it doubled again. During the worst week of the Great Recession of the late Aughts, 661,000 Americans filed for unemployment insurance. During the week of March 16, 2020, more than 3.3 million Americans did.

The federal government responded to this free fall with bold and immediate relief. It expanded the time window in which laid-off workers could collect unemployment and, in a rare recognition of the inadequacy of the benefit, added supplementary payments. For four months, unemployed Americans received $600 a week on top of their regular stipend, nearly tripling the average amount of the benefit. (In August 2020 the government reduced the bonuses to $300 a week.)

Because of the generous unemployment benefits—alongside stimulus checks, rental assistance, an expanded Child Tax Credit, and other forms of relief—poverty did not increase during the worst economic downturn in nearly a century. It fell, and by a tremendous amount. The US economy lost millions of jobs during the pandemic, but there were roughly 16 million fewer Americans in poverty in 2021 than in 2018. Poverty fell for all racial and ethnic groups. It fell for people who lived in cities and those who lived in rural areas. It fell for the young and the old. It fell the most for children. Swift government action didn’t just prevent economic disaster; it helped to cut child poverty by more than half.

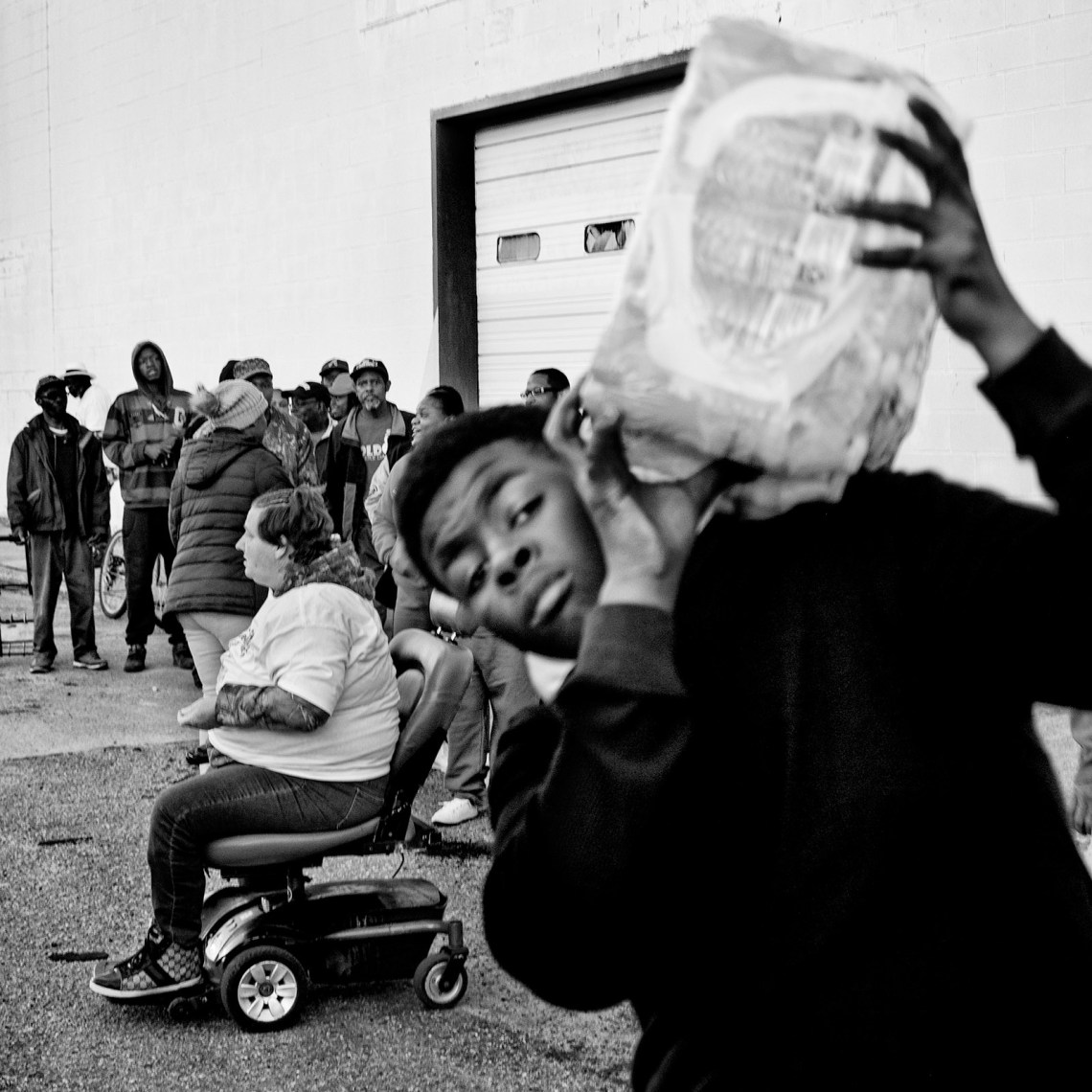

After years of inaction, the United States had finally made a major dent in the poverty rate. But a vocal subset of Americans seemed troubled that the government was doing so much to help. In particular they blamed the souped-up unemployment checks for the nation’s sluggish economic recovery. David Rouzer, a Republican congressman from North Carolina, tweeted a picture of a closed Hardee’s with the caption “This is what happens when you extend unemployment benefits for too long and add a $1400 stimulus payment to it.” Kevin McCarthy, then the House minority leader, wrote that Democrats “have demonized work so Americans would become dependent on big government.” Reporters fanned out across the country and interviewed small business owners who attributed their hiring headaches to the federal aid. “We had employees that still chose to take the unemployment and not stay on, which I thought was just unbelievable,” said Colin Davis, the owner of Chico Hot Springs Resort in Montana. “I just—when did everyone get so lazy?” It sounded obvious: America wasn’t getting back to work because we were paying people to stay home.

This hypothesis, as it turned out, was wrong. In June and July 2021, twenty-five states stopped some or all of the emergency benefits rolled out during the pandemic, including expanded unemployment insurance. This created an opportunity to see whether those states enjoyed a significant jump in their employment rates. But when the Labor Department released the August data, we learned that the five states with the fastest job growth (Alaska, Hawaii, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Vermont) had retained some or all of the benefits. States that had cut unemployment benefits did not experience significant job growth.

Why did we so readily embrace a story that blamed high unemployment on government aid when so many other explanations were available to us? Why didn’t we figure people weren’t returning to work because they didn’t want to get sick and die? Or because their jobs were lousy to begin with? Or because their children’s schools had closed, and they lacked reliable childcare? When asked why many Americans weren’t returning to work as fast as some people would have liked, why was our answer Because they are getting $300 extra each week?

Perhaps it’s because we’ve been trained since the earliest days of capitalism to see the poor as idle and unmotivated. The world’s first capitalists faced a problem that titans of industry still confront: how to get the masses to file into their mills and slaughterhouses to work for as little pay as the law and market allow. In his 1786 treatise A Dissertation on the Poor Laws: By a Well-Wisher to Mankind, the English doctor and clergyman Joseph Townsend proposed an answer. “The poor know little of the motives which stimulate the higher ranks to action—pride, honour, and ambition,” he wrote. “In general it is only hunger which can spur and goad them on to labour.”

But once you got the poor into factories, you needed laws to protect your property and lawmen to arrest trespassers and court systems to prosecute them and prisons to hold them. Big money required big government. But big government could also hand out bread. Early converts to capitalism saw aid to the poor not merely as bad policy but as an existential threat, something that could sever the reliance of workers on owners. Realizing this, early capitalists decried the corrosive effects of government aid. In 1704 the English writer Daniel Defoe published a pamphlet arguing that the poor would not work for wages if they were given alms. This argument was repeated over and over again by leading thinkers, including Thomas Malthus in his famous 1798 treatise, An Essay on the Principle of Population.

Advertisement

Fast-forward to the modern era and you still hear the same neurotic arguments. When President Franklin Roosevelt, originator of the American safety net, in 1935 called welfare a drug and “subtle destroyer of the human spirit”; or when Arizona senator Barry Goldwater complained in 1961 about “professional chiselers walking up and down the streets who don’t work and have no intention of working”; or when Ronald Reagan, campaigning for the presidential nomination in the late 1970s, kept telling audiences about a public housing complex in New York City where “you can get an apartment with eleven-foot ceilings, with a twenty-foot balcony”; or when in 1980 the American Psychiatric Association made “dependent personality disorder” an official diagnostic category; or when the conservative writer Charles Murray wrote in his influential 1984 book, Losing Ground, that “we tried to provide more for the poor and produced more poor instead”; or when President Bill Clinton in 1996 announced his plan to “end welfare as we know it” because the program created a “cycle of dependency that has existed for millions and millions of our fellow citizens, exiling them from the world of work”; or when President Donald Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers issued a report endorsing work requirements for the nation’s largest welfare programs and claiming that America’s welfare policies have brought about a “decline in self-sufficiency,” they were rehashing an old story—call it the propaganda of capitalism—that has been handed down from one generation to the next: that our medicine (aid to the poor) is poison.

Who we think benefits from that aid also deeply affects our views. Americans tend to believe (wrongly) that most welfare recipients are Black. And many Americans continue to believe Blacks have a poor work ethic. Anti-Black racism hardens Americans’ antagonism toward social benefits.

When welfare dependency dominated public debate in the 1980s and 1990s, researchers set out to study the issue. They found that most young mothers on welfare stopped relying on it within two years of starting the program. Most of those mothers returned to welfare sometime down the road, leaning on it for limited periods between jobs or after a divorce. Those who stayed on the rolls for long stretches were the exception to the rule. A review of the research in Science concluded that “the welfare system does not foster reliance on welfare so much as it acts as insurance against temporary misfortune.”

Today the problem isn’t welfare dependency but welfare avoidance. Simply put, many poor families don’t take advantage of aid that’s available to them. Only a quarter of families who qualify for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families apply for it. Less than half (48 percent) of elderly Americans who qualify for food stamps sign up to receive them. One in five parents eligible for government health insurance (in the form of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program) does not enroll, just as one in five workers who qualify for the Earned Income Tax Credit does not claim it. At the height of the Great Recession, one in ten Americans was out of work, but among that group only one in three drew unemployment.

There are no official estimates of the total amount of government aid that goes unclaimed by low-income Americans, but the number is in the hundreds of billions of dollars a year. Roughly seven million people who could receive the Earned Income Tax Credit don’t claim it, collectively passing up $17.3 billion annually. Combine that with the amount of money unclaimed each year by people who deny themselves food stamps ($13.4 billion), government health insurance ($62.2 billion), unemployment insurance when between jobs ($9.9 billion), and Supplemental Security Income ($38.9 billion), and you are already up to nearly $142 billion in unused aid.

We used to believe that welfare avoidance came down to stigma, that people weren’t signing up for aid because they found the experience too shaming. But research has started to chip away at this theory. Take-up rates of means-tested programs like food stamps are similar to those of some more universal (and less stigmatized) social insurance programs, like unemployment. When the government switched from food stamps in the form of actual stamps that you would conspicuously hand to a grocery store cashier to discreet Electronic Benefits Transfer cards that looked like any other debit card, there wasn’t a conclusive uptick in applications.

Advertisement

If the answer isn’t stigma, what is going on? The evidence indicates that low-income Americans are not taking full advantage of government programs for a much more banal reason: we’ve made it hard and confusing. People very simply often don’t know about aid designated for them or are burdened by the application process. When it comes to increasing enrollment in social programs, the most successful behavioral adjustments have been those that simply raised awareness and cut through red tape and hassle.

One intervention tripled the rate of elderly people getting food stamps by providing information about the program and offering sign-up assistance. Elderly households received a letter informing them they could apply for food stamps along with a number to call. Those who dialed the number were connected to a benefits specialist who helped callers fill out the application and collect the necessary documentation.

Another initiative significantly increased the number of workers who claimed the Earned Income Tax Credit just by sending out mailers, reducing the amount of text on the application, and using a more readable font. No kidding: using Frutiger font—that sturdy, confident typeface adorning Swiss road signs and prescription labels—helped bring millions more dollars to low-income working families.

The irony is that while politicians and pundits fume about long-term welfare addiction among the poor, members of the protected classes have grown increasingly dependent on their welfare programs. If you count all benefits offered, America’s welfare state (as a share of its gross domestic product) is the second biggest in the world, after France’s. But that’s true only if you include things like government-subsidized retirement benefits provided by employers, student loans and 529 college savings plans, child tax credits, and homeowner subsidies: benefits disproportionately flowing to Americans well above the poverty line. If you put aside these tax breaks and judge the United States solely by the share of its GDP allocated to programs directed at low-income citizens, then our investment in poverty reduction is much smaller than that of other rich nations. The American welfare state is lopsided.

In her book The Government-Citizen Disconnect (2018), the political scientist Suzanne Mettler reports that 96 percent of American adults have relied on a major government program at some point in their lives. Rich, middle-class, and poor families depend on different kinds of programs, but the average rich and middle-class family draws on the same number of government benefits as the average poor family.

Student loans look like they were issued by a bank, but the only reason banks hand out money to eighteen-year-olds with no jobs, no credit, and no collateral is because the federal government guarantees the loans and pays half their interest. Financial advisers can help you sign up for 529 plans, but those plans’ generous tax benefits will cost the federal government an estimated $28.5 billion between 2017 and 2026. In 2020 the federal government spent more than $193 billion on homeowner subsidies, a figure that far exceeded the $53 billion allocated to housing assistance for low-income families. For most Americans under the age of sixty-five, health insurance appears to come from their jobs, but supporting this arrangement is one of the single largest tax breaks issued by the federal government, one that exempts the cost of employer-sponsored health insurance from taxable incomes. It is estimated that in 2022 this benefit cost the government $316 billion.

Today, the biggest beneficiaries of federal aid are affluent families. In total, the United States spent $1.8 trillion on tax breaks in 2021. I can’t tell you how many times someone has informed me that we should reduce military spending and redirect the savings to the poor. I’ve met far fewer people who have suggested we boost aid to the poor by reducing tax breaks that mostly benefit the upper class, even though we spend over twice as much on them as on the military and national defense.

According to recent data compiling spending on social insurance, means-tested programs, tax benefits, and financial aid for higher education, the average household in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution receives roughly $25,733 in government benefits a year, while the average household in the top 20 percent receives about $35,363. Every year, the richest American families receive almost 40 percent more in government subsidies than the poorest American families.

But the rich pay more taxes, one might say. They do—but that isn’t the same thing as paying a larger share of taxes. The federal income tax is progressive, meaning that tax burdens grow as incomes increase, but other taxes are regressive, forcing the poor to hand over a larger share of their earnings. Take sales taxes. These hit the poor hardest, for two reasons articulated by the economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman in their book The Triumph of Injustice (2019). First, poor families can’t afford to save, but rich families can and do. Families that spend all of their money every year will automatically dedicate a higher share of their income to sales tax than families who spend only a portion of theirs. Second, when rich families do spend money, they consume more services than poor families, who spend their money on goods (gas, food), which are subject to more sales tax. The progressive design of the federal income tax is offset by the regressive nature of other taxes, including the fact that wealth (in the form of capital gains) is taxed at a lower rate than wages.

Saez and Zucman show that when all taxes are accounted for, we’re all effectively taxed at the same rate. On average, poor Americans dedicate approximately 25 percent of their income to taxes, while rich families are taxed at an effective rate of 28 percent, just slightly higher.

The American government gives the most help to those who need it least. This is the true nature of our welfare state.

The implications are felt in our bank accounts, but more deeply in our psychology and civic spirit. Studies have found that Americans who claimed the Earned Income Tax Credit weren’t more likely to see themselves as government beneficiaries than those with a similar background who didn’t or couldn’t claim the benefit. But people who received cash welfare through such programs as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families did see themselves as beneficiaries of government aid. Similarly, those who relied on student loans or drew on 529 plans were not more likely to recognize the government’s role in their lives than people from similar walks of life who didn’t rely on these programs. But Americans who benefited from the GI Bill had a clear sense that they had been granted new opportunities through state action. Americans who rely on the most visible social programs (like public housing or food stamps) are also the most likely to recognize that the government has been a force for good in their lives, but Americans who rely on the most invisible programs (namely tax breaks) are the least likely to believe that the government has given them a leg up.

Families who benefit most from government largesse in the form of tax breaks harbor the strongest antigovernment sentiments. Overwhelmingly, voters who claim tax breaks are the very ones who oppose deeper investments in programs like affordable housing, just as those who received employer-sponsored health insurance were the ones pushing to repeal the Affordable Care Act. It’s one of the more maddening paradoxes of political life.

How do we square this? How do we reconcile the fact that enormous government tax benefits go unnoticed by middle- and upper-class families who claim them, which breeds resentment among those families toward a government perceived to be giving handouts to poor families, which in turn leads well-off voters to mobilize against government spending on the poor while also protecting their own tax breaks that supposedly aren’t even noticed in the first place?

As I see it, there are three possibilities. The first is that many of us understandably have a hard time viewing a tax break as something akin to a government check. We see taxation as a burden and tax breaks as the state allowing us to keep more of what is rightfully ours. Psychologists have shown that we tend to feel losses more acutely than gains. The pain of losing $1,000 is stronger than the satisfaction of winning that amount. It’s no different with taxes. We’re apt to think much more about the taxes we have to pay than about the money delivered to us through tax breaks.

This is by design—the result of the United States intentionally making tax filing exasperating and time-consuming. In Japan, Great Britain, Estonia, the Netherlands, and several other countries, citizens don’t file taxes; the government does it automatically. Taxpayers check the government’s math, sign the form, and mail it back. The process can be completed in a matter of minutes, and more important, it better ensures that citizens pay the taxes they owe and receive the benefits owed to them. If Japanese taxpayers believe their government has overcharged them, they can appeal their bill, but most don’t. There’s no reason Americans’ taxes couldn’t be collected this way, except for the fact that corporate lobbyists and many Republican lawmakers want the process to be painful. “Taxes should hurt,” President Reagan famously said.

This is a case where the packaging is just as important as the gift. But both welfare checks and tax breaks boost a household’s income, contribute to the deficit, and are designed to incentivize behavior, like seeing a doctor (Medicaid) or saving for college (529 plans). We could flip the delivery system to achieve the same ends, extending welfare to the poor by cutting payroll taxes for low-income workers (as France has) while replacing the mortgage interest deduction with a check mailed to homeowners each month. Same difference.

Given this, I suspect there might be another reason for our unwillingness to acknowledge the invisible welfare state: entitlement. Maybe middle- and upper-class Americans believe they—but not the poor—deserve government help. This has been a long-standing explanation among liberal thinkers: that Americans’ hardwired belief in meritocracy drives them to conflate material success with deservingness. I don’t buy it. We are bombarded with too much clear evidence to the contrary. Do we really believe the top one percent are more deserving than the rest of the country? Do we have the audacity to point to housekeepers with skin peeling from chemicals or berry pickers who can no longer stand up straight or the millions of other poor working Americans and claim that they are stuck at the bottom because they are lazy?

Even in our personal lives, we see people getting ahead not because of their gumption and effort but because they are tall or attractive or know a guy or received a fat inheritance. Our lives are tangibly shaped in countless ways—not only by things beyond our control but also by the relentless irrationality of the world. Every day we confront the capriciousness of life—the unfair, stupid ways our future is determined by background or chance.

Most of us believe that working hard helps us get ahead—because of course it does—but most of us also recognize that advantages flow from being white or having highly educated parents or knowing the right people. We sense that our bootstraps can be pulled up only so far, that self-help platitudes about grit and self-control and putting in the hours is fine advice for our children but no substitute for a theory of how the world works. Most Democrats and Republicans alike today believe that poverty is caused by unfair circumstances, not by a lack of work ethic.

This brings us to the third possible explanation for why we accept the current state of affairs: we like it.

It’s the rudest explanation, I know, which is probably why we cloak it behind all sorts of justifications and quick evasions. But as the civil rights activist Ella Baker once put it, “Those who are well-heeled don’t want to get un-well-heeled,” no matter how they came by their coin. Tax breaks are nice if you can get them. In 2020 the mortgage interest deduction allowed more than 13 million Americans to keep $24.7 billion. Homeowners with annual family incomes below $20,000 enjoyed $4 million in savings, and those with annual incomes above $200,000 enjoyed $15.5 billion. Also in 2020, more than 11 million taxpayers deducted interest on their student loans, saving low-income borrowers $12 million and those with incomes between $100,000 and $200,000 $432 million. In all, the top 20 percent of income earners receives six times what the bottom 20 percent receives in tax breaks.

We have chosen to prioritize the subsidization of affluence over the alleviation of poverty. And then we have the gall—the shamelessness, really—to fabricate stories about poor people’s dependence on government aid and shoot down proposals to reduce poverty because they would cost too much. Glancing at the price tag of some program that would cut child poverty in half or give all Americans access to a doctor, we ask, “But how can we afford it?” How can we afford it? What a sinful question. What a selfish, dishonest question, one asked as if the answer weren’t staring us straight in the face. We could afford it if the well-off among us took less from the government. We could afford it if we designed our welfare state to expand opportunity and not guard fortunes.

This Issue

April 20, 2023

A Formative Loss

300 Years of ‘Too Big to Jail’