On July 14, 1958, Abdul al-Karim Qassim led a coup in Iraq that toppled King Faisal II, an uncle of the Jordanian monarch, King Hussein. Fearful that the nationalists and antimonarchists in Jordan might carry out a similar coup against his regime, Hussein declared martial law and ordered the arrest of large numbers of known nationalist leaders.

One of those leaders was my father, the Palestinian lawyer Aziz Shehadeh. He spent two scorching months that summer at the desert prison of Al Jafr. I don’t remember his return home after that ordeal. I have a memory of seeing a photograph of him with a dark beard covering his face, a shaved head, and large, fiery, dark brown eyes. Was it taken at the desert prison and smuggled out, or was it a false memory, a trick of the imagination? Yet he must have had a long beard, although I don’t recall him with one. My sister told me he was whisked away, probably by my mother, as soon as he arrived home and rushed off to the barber for a shave so that we would not see him bearded. But I have no memory of that either.

How is it that I remember none of this? How is it that his unjust imprisonment under such harsh conditions didn’t make my father a hero in my eyes? Years later I would realize that my attitude toward my father was never one of admiration. Not being aware of the extent and sheer number of battles he fought during his lifetime of legal and political struggle for Palestinian rights, I never understood the measure of his anger, disappointment, and unhappiness. In time I could have come to show more kindness and understanding toward him. He was healthy and took good care of himself. Yet his death in 1985 at the hands of a murderer—a squatter on land in Hebron belonging to the Anglican Church who may have acted as an Israeli collaborator, against whom my father was handling an eviction case—left no more time for that.

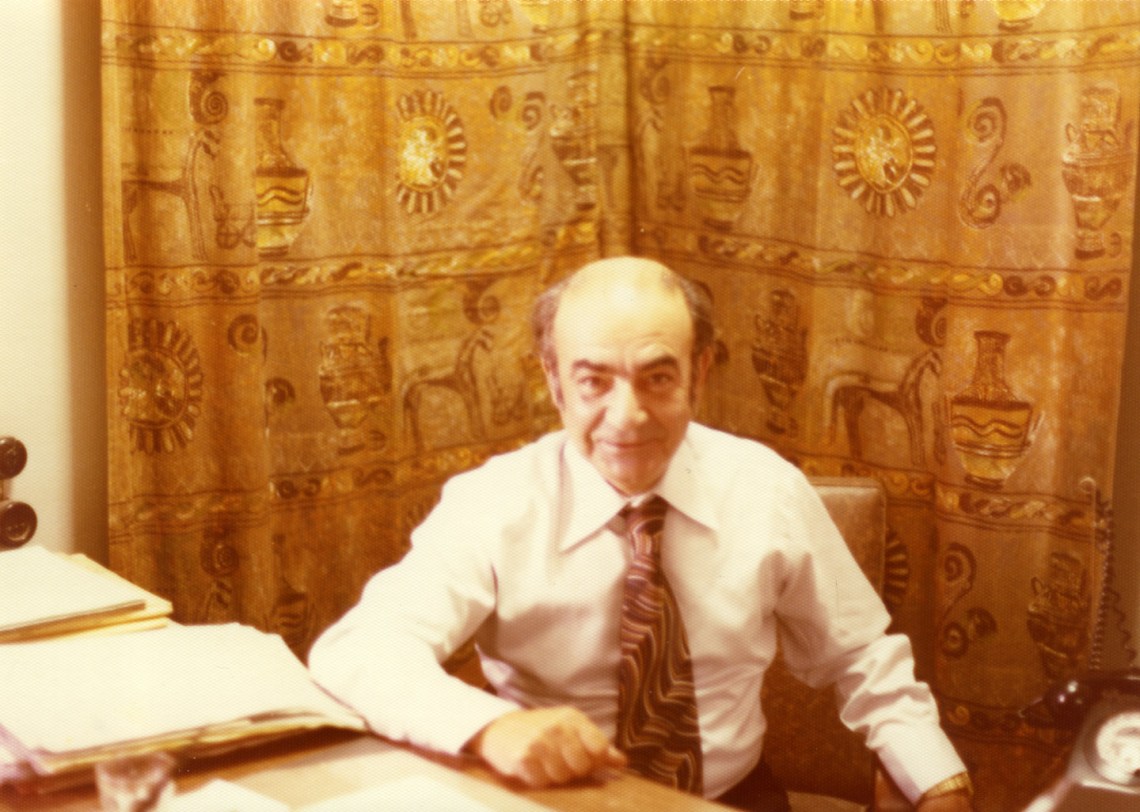

My father was seventy-three when he was murdered, a few years older than I am now. But to the man of thirty-four I was then he seemed very old, someone to whom I could not relate. When the time came for finalizing the cover for my new book, We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I, the designer chose a picture of my father with his arm around my cousin Walid, thinking it was me. When I pointed out the mistake, the designer asked for a similar picture of me embracing my father. I searched all the family photos; none was to be found. It was a sad confirmation of what I had lost in never having gained that closeness with my father, who was an emotional and loving man. Why, when we worked on similar issues, were we so unable to communicate? Why, with our respective experiences of Palestine, his after the Nakba and mine after the 1967 war, did we not see the similarities in our trajectories and help each other understand and endure?

During my father’s final year, I could see how busy he was putting his papers in order. I wondered whether he was preparing to write his memoirs, but it seems he didn’t intend to. All of those files remained in his house until I eventually moved them to mine. Two years ago, as I have recounted in these pages, I decided to open them: file after file, neat and well-organized, documenting his political engagements. They included his assiduous work on the return of the refugees to the homes from which they were forced in 1948; his petition to the British Labour Party against the British commander of the Jordanian army, Glubb Pasha, under whose brutal rule he was living; and a number of precedent-setting legal cases.

*

My father lived for thirteen years in Jaffa, where he established his law practice and later his matrimonial home. When he was forced to leave in April 1948 he was certain that in the worst case—even if other parts of Palestine were lost to the Jewish state—the city, which according to the 1947 UN Partition Scheme was part of the Arab state, would return to Arab hands. In his file on the return of the refugees I read how his hopes were raised on December 11, 1948. That day the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 194, which stated that “refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return.” On the same day, the UN established the Palestine Conciliation Commission to carry the resolution out. Knowing that they could not leave the task to the UN alone, a group of Palestinians, my father among them, established the Ramallah Refugee Congress (later called the Arab Refugee Congress), which represented 300,000 refugees. Its main aim was to “uphold the right of the refugees to return to their homes.”

Advertisement

In April 1949 the Congress was invited to represent Palestine at the Lausanne Conference, which was convened by the UN Palestine Conciliation Commission to resolve disputes arising from the war, especially concerning refugees. My father and three of his colleagues travelled to Lausanne but were not accepted by Israel as a separate delegation. They were stateless, and Israel only negotiated with states.

For several years my father and others continued to look for ways to return home to Palestine. Unbeknownst to them, secret negotiations had been underway since 1947, before the British Mandate of Palestine ended, between King Abdullah and the Zionist leaders, both of whom hoped to prevent the birth of a Palestinian state under their common enemy, Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Palestinian head of the Arab Higher Committee. The British government, for its part, was exploring the possibility that the Arab parts of Palestine, which it believed would be unviable as an Arab Palestine on their own, could be fused with the newly established Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan. At a secret meeting in London in February 1948, Ernest Bevin, the UK foreign secretary, gave King Abdullah the green light to snatch part of Palestine, provided that the king’s forces stayed out of the areas that the UN partition plan allotted to the Jews.

I can almost hear father’s impassioned voice summing up the steps he and other Palestinian leaders had taken to ensure the return of the refugees to their homes and property: We took our case to Lausanne. There Israel refused to negotiate with us and the Arab states continued denying us the right to speak for ourselves: they wanted to speak for us, to do what was in their interest, not in ours. And yet we addressed the UN Palestine Conciliation Commission and later US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles when he visited, all to no avail. We wrote to the President of the United States in 1952. We organized and spoke out, sparing no effort to do what we thought was right, and yet in the end the initiative was snatched out of our hands and we were left at the mercy of a leadership that we did not trust. It was a battle waged to determine who would represent the refugees, and Jordan won. The Jordanians ended up betraying us to pursue their own dreams of expanding their territory until it encompassed the western bank of the River Jordan, only to lose the West Bank, including eastern Jerusalem, in the 1967 war, in which they made little effort to fight back.

The experience and knowledge my father accumulated during his years of political activity convinced him that the Palestinians could not rely on the Arab states. They needed to take the initiative to call for the establishment of a state of their own. The central struggle, he resolved, should be for self-determination. Only as a state would Palestinians acquire the standing they needed to regain their legitimate rights.

The beginning of the Israeli occupation in 1967 marked a fundamental change in my father. No longer was he apathetic about politics, as he had become in the late 1950s when he was living under Jordan’s rule. He found new energy and once again applied himself to political work. A few weeks after Israel occupied the West Bank, eastern Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, he submitted a proposal to establish a Palestinian state next to Israel along the 1947 partition borders, with its capital in the Arab section of Jerusalem, and hold negotiations over all other outstanding issues.

The UN partition plan of 1947 had recognized the rights of the Palestinians to a state, just like Israel’s. Why not invoke this now, he argued, and declare a state according to that partition plan, and negotiate peace with Israel? Self-determination is a fundamental right of every nation, so why deny it to the Palestinians? When he visited Jaffa after 1967 he saw that it was basically unchanged, looking more or less just as it had when they had left it in 1948. It was not too late for a Palestinian state, according to the partition plan that had left Jaffa under Arab control. He got the support of fifty prominent Palestinian leaders from different parts of the occupied territories, handed the proposal to two Israeli emissaries to present to the Israeli government, and awaited a response.

All my father’s previous work on the Palestinian case led him to this bold and courageous conclusion. But it went against the revolutionary zeal that was sweeping the Palestinian diaspora in the immediate aftermath of the war. As soon as his plan became known, insults and accusations were hurled at him from all sides for proposing the establishment of a Palestinian state next to Israel. As a sixteen-year-old, unaware of my father’s political activities after the Nakba, I wanted to give vent to the raw hatred I felt toward Israel as the occupier of our land. But I couldn’t. I had to be calm, unemotional, resilient, and supportive of my father.

Advertisement

Later I would come to appreciate how strongly my father believed that it was incumbent upon him to speak and act. He was a pioneer, ahead of his peers. Surely the future has vindicated his belief that it would be difficult, and possibly even futile, to try to win rights without the backing of a state. In 1967 there was not yet a single Israeli settlement in the occupied territories. Now the establishment of a Palestinian state next to Israel has become the official PLO strategy. Yet after more than half a million Israeli Jews have moved to live in settlements in the West Bank, this goal is now unattainable.

*

There were more revelations in my father’s papers. One file documented a 1954 case he argued before the district court in Jordan against Barclays Bank for refusing to allow Palestinian clients to withdraw their money from branches in Israel. When Israel declared itself a state it ordered “all commercial banks operating within its territory,” as the historian Sreemati Mitter has written, “to ‘freeze the accounts of all their Arab customers and to stop all transactions on all Arab accounts.’” This meant that the refugees were unable to withdraw money they had deposited with the Arab and Barclays banks branches in areas now under Israeli control from any branch outside Israel. The order further impoverished Palestinians who had lost all their business, houses, land, and properties to Israel in the Nakba.

My father’s case against the bank succeeded in releasing these assets. But when he travelled to London to work out procedures for the release of the funds, the Jordanian foreign minister claimed that the negotiations had taken place with Israel, which the minister said amounted to an act of treason. My father got word that every border guard in Jordan had been ordered to arrest him immediately upon his return—his reward for winning the case. He had to spend twenty-seven months in exile in London, Rome, and Beirut before he was allowed to return home to Ramallah.

In another bulky file lay a memorandum dated June 23, 1955, that my father and his colleague Muhammad El Yahya wrote to members of the British Labour Party during his exile in London. In it they complained about the activities of Glubb Pasha, whom they accused of the fraud and harsh measures adopted during the Jordanian parliamentary elections of 1954. Reading this memo, I marveled at my father’s fearlessness. And yet his efforts at lobbying the British to remove their man in Jordan seemed overly optimistic. With all he knew of the British and their behavior during the Mandate, when they tortured prisoners, demolished homes, and hanged rebels, how could he expect justice from them? Why would they want to change their policies and remove their agent in Jordan just because of my father’s accusations?

It is to be regretted that the blocked accounts case was not celebrated by the authorities in Jordan. Nor did it inspire others to use the law in the struggle against Israel: after 1967 the Palestinian leadership took no notice of the case as an example of what could be done to fight illegal Israeli actions. This failure to consider the law as one form of struggle meant that the PLO neglected to follow and confront the changes Israel made to the local law in the West Bank during the first twenty-five years of its occupation. When negotiations took place in Oslo between Israel and the PLO in 1993 the Palestinian negotiators were unable to reverse these changes, which enabled Israel to establish more Jewish settlements and link them to the other side of the Green Line. My father would have been appalled at the total absence of legal grounding for the talks.

*

It took decades for the possibility of legally opposing the occupation to take root. I was part of that struggle. Through my organization Al-Haq we challenged Israel’s violations of international law, its land grabs, and its illegal policy of settling Israelis in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and we raised cases against some of the proposed changes in the law. I also attended UN meetings on “the question of Palestine” in far-flung corners of the world. How similar my work was to what my father had done three decades earlier! And yet my father never commented on the similarity between our two struggles and took little interest in my human rights work.

In 1983, at a conference in Jakarta, I met his star trainee in Jaffa, Muhammad El Farra, who had become assistant secretary general of the League of Arab States. When I got back and talked to my father he was unenthusiastic about the conference and didn’t want to hear about it. I could not understand why. Now I realize what a farce those gatherings were. We would present papers about what was taking place in the occupied territories and then argue endlessly about a concluding statement, as if everything rested upon it. But none of it really mattered, neither the papers nor the resolutions. They were read by no one and ended up gathering dust on the shelves of the UN. My father knew this but spared me the revelation. He never told me how his own efforts had ended. Did he perhaps assume I knew? But how could I? We were not in sync. I had been lagging behind by some thirty years.

I was in my prime, going full speed ahead with my work, thinking the world of myself. Having been a slow developer, I was beginning to realize my potential and experience the young manhood that had been interrupted by the start of the Israeli occupation in 1967. I did not want anyone stopping me or casting doubt on the work in which I was so enthusiastically engaged. I believed then that I was breaking new ground in legal resistance against Israel. I had no idea that my father had done the same years earlier. Nor did I know that it was from him that I got my public spirit and the sense of responsibility that made me regard the failures of my people as a personal flaw for which I must bear the blame. It was this that pushed me to write all those articles and books about Israel’s policies in the occupied territories, to explain, to document, to advocate.

For years I lived as a son whose world was ruled by a fundamentally benevolent father with whom I was temporarily fighting. I was sure that we were moving, always moving, toward a happy family and that one day we would all live in harmony. When he died I had to wake up from my fantasy. There was not enough time for the rebellion and the dream. The rebellion had consumed all the available time. I turned around to ask my stage manager when the second act would start and found that there was none. I was alone. There was no second act and no stage manager. What hadn’t happened in the first act would never happen. Life moves in real time.

The period after my father’s murder was the most shattering and arduous of my life, due not only to the emotional impact of losing him but also to the long and futile process of following the Israeli investigation of the murder, which has continued to this day. Most recently I have petitioned the Israeli high court to instruct the police to explain why they refuse to allow me to review the investigation file. It was also a time when I was witnessing the slow transformation of our country and the destruction of our future in it. The building of Israeli settlements and their roads, water, and electricity was devastating the landscape. These were years filled with anxiety and worry about our future. We watched our world being changed before our eyes, the area left for us constantly shrinking, rendering ever more remote the possibility of establishing the Palestinian state there that my father had envisioned.

As I was finishing my book, I had an imaginary conversation with my father. I informed him that history had proven him wrong. The occupier has won. The word “occupation” has been dropped from Israel’s vocabulary. The curriculum taught in their schools tells students that the Land of Israel is theirs and that the Palestinians have no rights over that land. Last year the world watched as 25,000 Israelis marched through the Old City declaring that Jerusalem is for Israelis alone, shouting “death to Arabs,” and, according to one report, “banging on the metal shutters of Palestinian shops and restaurants with sticks and flagpoles.” By the time the marchers reached the Western Wall, “Israeli flag stickers and graffiti featuring the Star of David in blue paint and pen had been left behind on doors and walls as well as in the plaza in front of Damascus Gate.”

On February 26, in the Palestinian town of Huwara, two settlers from the nearby Har Bracha settlement were murdered by a Palestinian militant. That night some four hundred settlers went on a five-hour rampage of revenge without being stopped by the Israeli army or police. One Palestinian was killed and many more injured, including four left in serious condition. At least fifteen houses were burned, one with the family still inside. Twenty-five cars were set on fire. Commenting on the pogrom, Israel’s national security minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir, said, “Our enemies need to hear a message of settlement, but also one of crushing them one by one.”

“You underestimated Israel’s power, resourcefulness, and long-term planning,” I want to tell my father. I imagine this would be his response: You say they’ve won because they deny the Palestinians any rights over the land and have dropped you out of their consciousness. This only means that they’ve succeeded in deceiving you as well. You think that because they’ve made you invisible, they’ve won? It pains me to hear you put it like that. This is a recipe for perpetual war. Don’t you realize that the only victory is the achievement of peace between our two peoples? How it saddens me to see that the only relations between you are those of master and slave: relations of hatred and exploitation. And yet you call their denial of Palestinians their victory. The only real victory is when we’ve both won.