The poster for Prima Facie, a one-woman play by Suzie Miller, shows two faces of the actress Jodie Comer. In one she is placid and wearing a barrister’s wig; in the other she’s screaming. A copy of the poster is folded up in the playbill handed to theatergoers. On its back are statistics detailing the prevalence and rare punishment of sexual assault in the United States. A vague call to arms is printed over Comer’s howl: “On the face of it something has to change.” Before the curtain rises, the theater thumps with songs from an album called Prioritise Pleasure by the British musician Self Esteem, who designed the show’s music. Choruses of women belt anthemic lines about reclaiming confidence after hardship and heartbreak.

The gripping, beautifully acted, didactic, and worrisome play that follows, which won England’s Olivier Award for Best New Play and has been nominated for four Tony Awards, is about an English lawyer named Tessa Ensler who is righteous about her work representing men accused of sexual assault, before she is assaulted herself. On the stand, she struggles to say what happened with the clarity that courtrooms demand. The play presents tenets of justice, like the presumption of innocence, in a grimmer light when they help acquit the man who raped her. The effect of this neatly constructed plot is to question whether the law is designed to give justice to women who have been sexually assaulted. Miller’s answer is that it is not.

A misprint on the back of the poster hints at what is amiss in this treatment of a familiar but important subject. It states that 97.5 percent of everyone arrested for sexual assault walks free. In fact, that’s the percentage of people who get away with committing the crime in the first place. The error is no fault of Miller’s, but it echoes a misdirection at the center of her script, which focuses narrowly on injustice in the courtroom, where a tiny portion of survivors end up. By suggesting that the reason rape goes unpunished is our onerous standards for testimony at trial, the play may make the audience wonder whether defendants simply have too many rights.

*

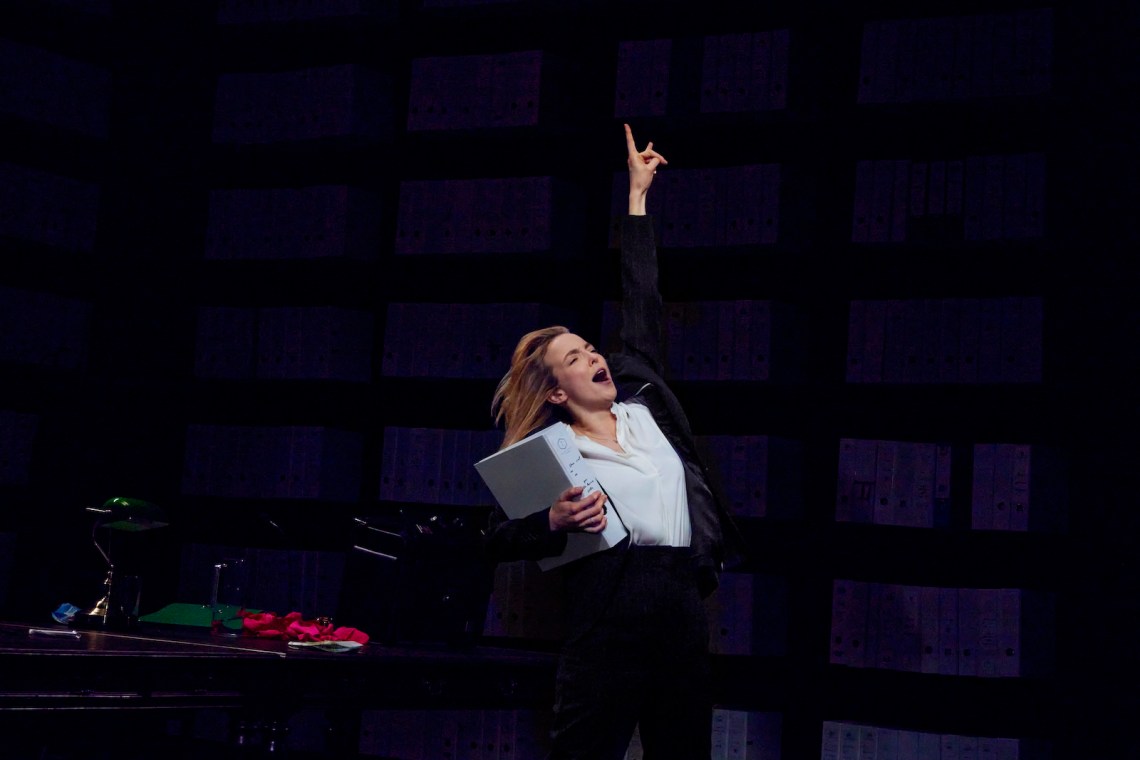

Tessa Ensler has left behind a mother who cleans and a brother who brawls. We meet her after she graduates from England’s top law school, wearing a suit that hangs loose, her blonde hair blown out, swaggering around her office, and showing off how she cross-examines. “I let him feel his control, feel safe. Then, tip-toe, tip-toe,” she says, before catching the imaginary witness in a contradiction: “Bang! I fire four questions like bullets. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Face, shock. Utter annihilation.” She has demolished the witness’s credibility and her client goes free. It is a perfect role for Comer, famous for her portrayal of a psychopathic assassin in Killing Eve, where it was just as fun to watch her kill.

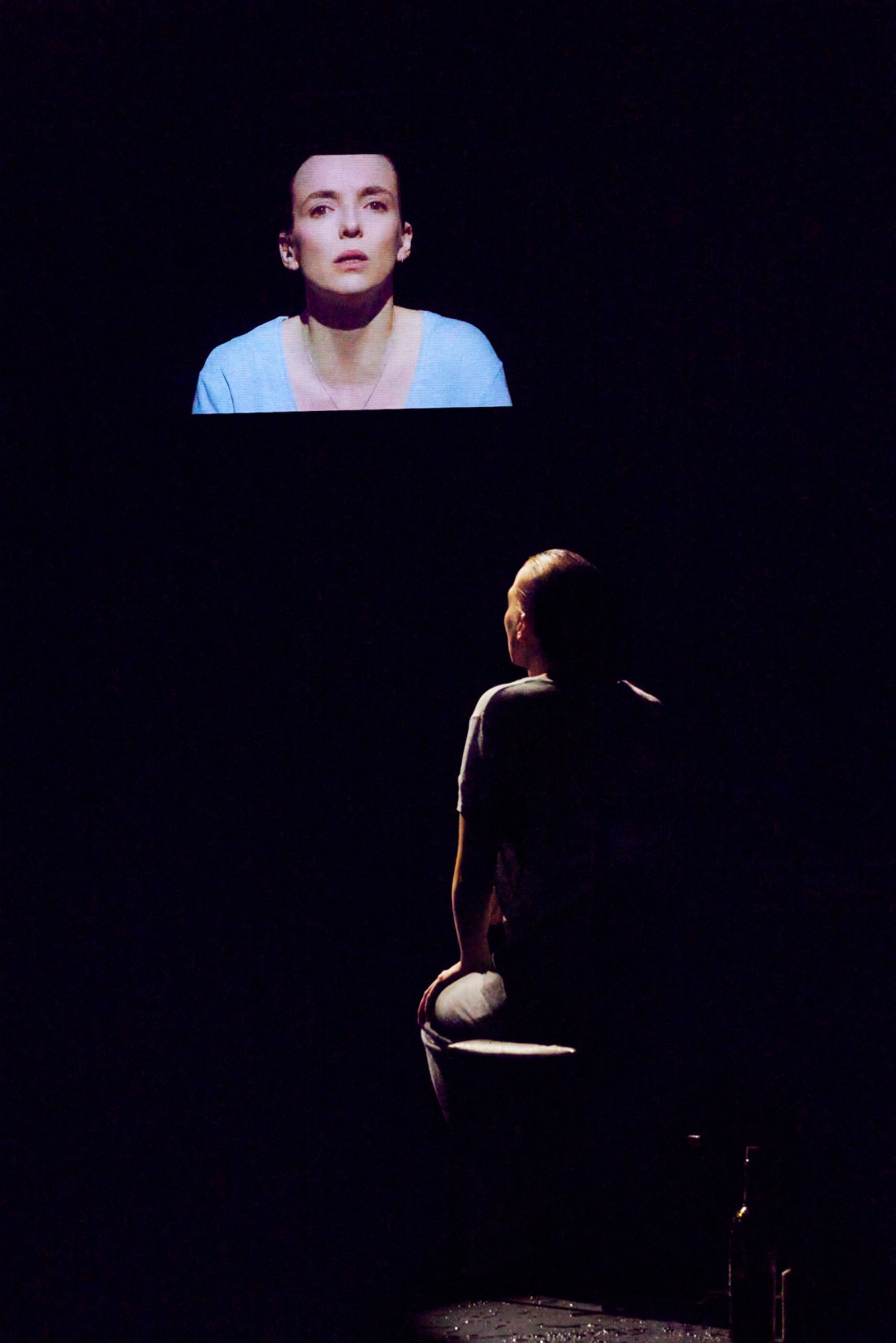

Under what is called the “cab rank rule” in English law, Tessa must accept whatever criminal cases her schedule allows. She also believes defending men accused of rape is virtuous, because “due process is everything” and the presumption of innocence forms the “bedrock of how you keep a society civilized.” Tessa sees it as her duty to test the state’s story for weaknesses. That Comer can convey this philosophy without lecturing is one of many wonders in her performance. She transforms a stage empty except for tables, lamps, chairs, and many rows of binders into a courtroom, train, club, apartment, and childhood home. The set is framed by a sleek, thin square of white light that flashes to accentuate moments of suspense.

Tessa’s unflinching certainty about her values signals that they are due for a challenge. She changes into a green cocktail dress onstage, discreetly slipping off her trousers from underneath, and narrates a date with a fellow barrister. “Julian meets me at the Japanese place on the corner. We talk about work, life, books, everything.” She describes how the two go back to her apartment, feed each other gelato, “kiss in icy bliss,” have sex, and doze off. “It’s nice,” she says a few times. Then she runs to throw up in the bathroom. (Comer drapes herself over a chair and heaves. Even her vomiting is virtuosic.) After Julian carries her back to bed, he starts kissing her. She tells him no and that she needs to brush her teeth, but he “keeps kissing me.”

I move my face. His hands are all over me. I feel sick still. Somewhere in the corners of my mind, I hear him say: “Just lay there and let me make love to you.” I squirm again. I feel his hands and legs pushing against me. I am suddenly very awake. He is on top of me but his hand is on my face.

The invisible rape is almost too clear.

Advertisement

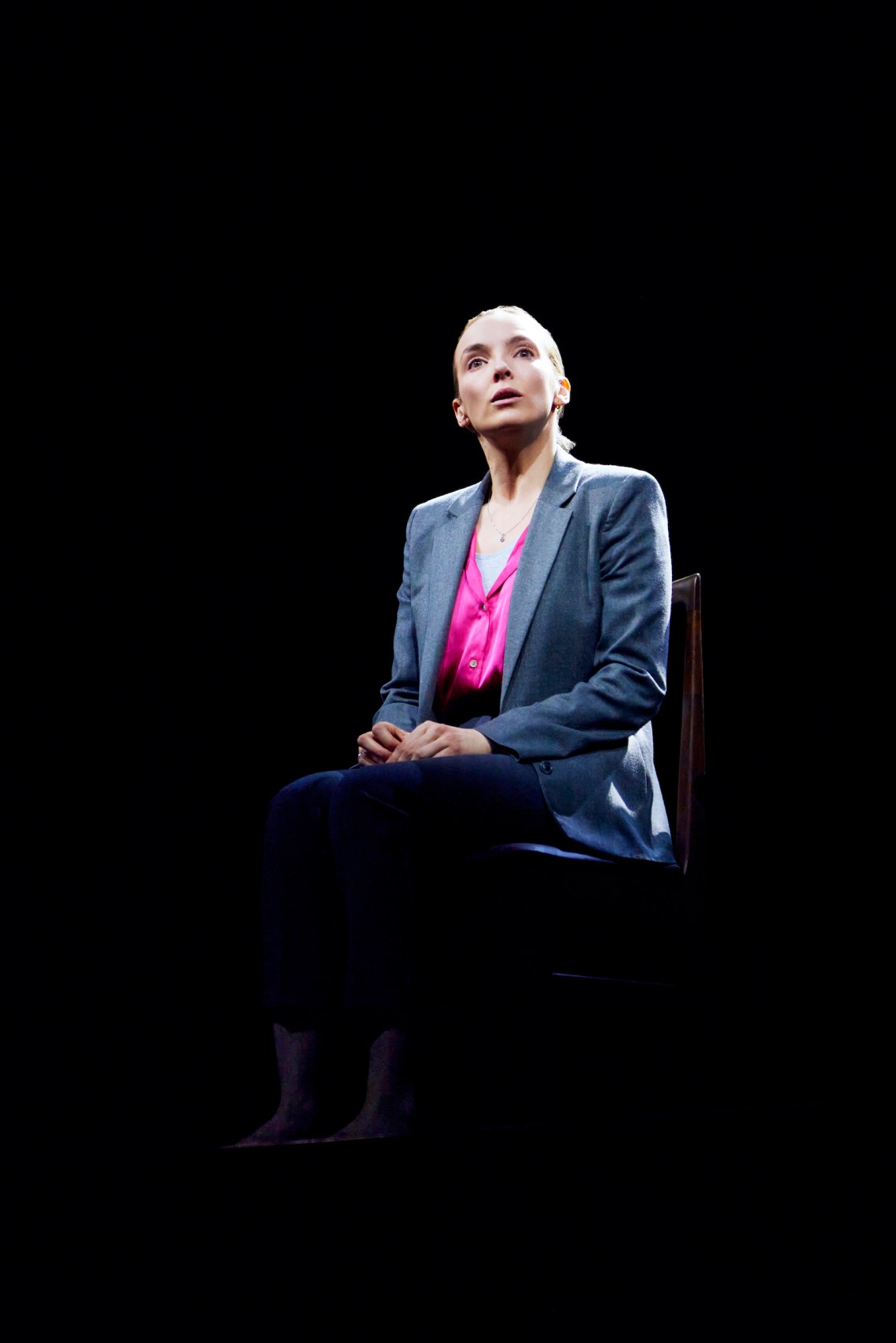

Afterward, she walks out into the rain. Her damp hair is pulled into a bun for the play’s second half, while she reports the assault and presses for Julian’s prosecution. The two years that she must wait for his trial are depicted through a digital count of passing days, projected onto the back wall of the stage. Tessa knows her story is vulnerable because it is the kind she has dismantled in court many times. She was drunk, invited Julian to her apartment, took off her clothes, and had willingly slept with him. Julian’s defense attorney can spin this as evidence that she consented, or at least that Julian reasonably believed that she had. Testifying at his trial—she sits on a chair atop a desk, to replicate the witness stand—the sharp-tongued barrister becomes halting and unsure. During her cross-examination, we only hear her answers: “Yes I think so.… I don’t know. Maybe my idea.… Um, I don’t remember.… Um, I don’t understand.” It is Julian’s silence against her ums and scrambled mind. The jury finds him not guilty.

*

Tessa’s experience on the stand is enlightening. It makes her reconsider whether muddled testimony means that a witness is lying. When the law refuses to recognize her rape, she must rethink whether there is no “real truth, only legal truth.” During Julian’s trial she looks straight at the audience and the lights go up inside the John Golden Theatre for a speech that is more sermon than soliloquy. “Now I know,” she says, “the lived experience of sexual assault is not remembered in a neat, consistent, scientific parcel.”

Her argument is that cross-examination catches contradictions that unfairly impeach a rape victim’s credibility. If she misremembers “peripheral details” or gets “rattled by reliving the nightmare in court,” her shakiness provides easy fodder for doubt. “It is because of this that she is so often disbelieved,” Tessa says about a hypothetical victim. She blames the “male-defined system of truth” for failing to credit accusations of rape that are true but spottily remembered, and wonders whether consistency should be the “litmus test of credibility” in sexual assault trials.

This may remind American audiences of other public displays of disbelief. When Christine Blasey Ford testified to the Senate Judiciary Committee in September 2018 about her assault by then–Supreme Court candidate Brett Kavanaugh when they were both teenagers, Republicans attacked her credibility. “She can’t tell me the house,” Lindsey Graham told reporters, “she can’t tell me the month of the year.” An assessment from Republican senators said that Ford had “no memory of key details,” including “how she got from the party back to her house,” and claimed that this raised “significant questions” about her story.

Ford acknowledged blur in her memory. Like Tessa, she could not recall every detail, though the central one was vivid: “the uproarious laughter” between Kavanaugh and his friend as they assaulted her. The law professor Deborah Tuerkheimer writes about the hearing in her 2021 book, Credible: Why We Doubt Accusers and Protect Abusers. She quotes a psychologist who explains that, in moments of acute stress, the brain’s hippocampus tends to encode and store peripheral details incompletely. This well-documented phenomenon was mentioned by Senate Democrats at Ford’s hearing to clarify why she could not remember everything.

The extent of Prima Facie’s argument is that women don’t get justice because expectations of testimony clash with how rape is experienced and recalled. But that is a small part of a much bigger story. The fragmentation of memory also afflicts other survivors of trauma, like soldiers, police officers, and victims of nonsexual crimes, who do not face the same routine skepticism. We can and do credit imperfect testimony. The question remains why we are less likely to do so when women talk about sexual assault. Lindsay Graham had reasons for finding holes in Ford’s story—among other things, he wanted a Court that would constrain women’s freedom by taking away the right to abortion. Judges and jurors won’t have such instrumental motives, but none will be free from biases, assumptions, insecurities, and investment in a world that favors men. To fully grasp the problem the play takes on, you have to look beyond legal standards.

This is especially true since most sexual assaults don’t make it to court. In the United States, less than a third are reported; in England, it is estimated to be a sixth. Even fewer lead to arrests, and fewer still result in criminal charges. Taking those numbers seriously may lead to different conclusions than Tessa’s. The fact that so many rape kits go untested, for instance, suggests that police do not merely disbelieve women but deprioritize sex crimes. In her recent book Becoming Abolitionists, the American activist and lawyer Derecka Purnell notes that much sexual violence is committed by the partners and spouses of victims. She recalls women from her church who did not call the cops because they relied on their partners for financial support and help raising children. Those structural problems would not be solved by changes to criminal law.

Advertisement

While Prima Facie takes aim at the “male-defined system of truth” in the courtroom, it never questions our reliance on the other systems—policing and prisons—that men have built. After a London Met officer raped and murdered a woman named Sarah Everard two years ago, several feminist groups there organized against a bill that would give police more money. They argued that law enforcement, rather than protecting women, too often abused them. The reality of that kind of violence is far removed from this play. At the end, Tessa describes looking out into the courtroom at Julian’s trial and catching the eyes of a kind female police officer who had squeezed her arm “like a friend, a sister.” She says that looking at the officer makes her “feel something good.”

*

Tessa’s bluster and confidence in the play’s first half recalls an interview with Donna Rotunno, a lawyer who has represented Harvey Weinstein and many other men accused of sexual assault. Rotunno tried to justify her work to Megan Twohey, who helped break the story about Weinstein for The New York Times. Rotunno said that she was just looking for “fairness,” that cross-examining alleged victims merely helped “a trier of fact, whether that be a judge or a jury, determine if they think their story is credible,” and that the Constitution guaranteed the right to confront witnesses. At the end of the interview Twohey asked Rotunno if she had ever been sexually assaulted. She said no, then paused, then elaborated: “Because I would never put myself in that position.” Prima Facie suggests the perils of that hubris, and its lesson about the gaps in traumatic memory encourages us not to silence victims who cannot tell their stories perfectly.

But you can too easily leave the theater thinking that the reason men get away with sexual assault—rather than structural inequality or cultural norms outside of the courtroom—is that alleged victims are probed too hard at trial. The plot is structured like a moral makeover, from a “before” in which Tessa is passionate about due process to an “after” that makes that commitment look naive. As if anticipating the objection, Miller, the playwright, has insisted in interviews that she still believes defendants must be innocent until proven guilty. In declaring merely that “something must change,” though, the play leaves the audience to ponder changes that would diminish the rights of the accused.

According to an interview with Playbill, Miller is part of a group of barristers called TESSA that is discussing changes to sexual assault law in the UK. One of their proposals is for defendants plausibly accused of assault to have to prove their innocence. Once a complainant presented evidence that she had not consented, the burden would shift to the defendant to demonstrate why he thought that she had. That change would imperil the presumption of innocence, to say nothing of the right to remain silent.

Prima Facie chafes against its form. To make its point within the confines of dramatic logic, it forces its main character into trauma that transforms her. This could be mistaken, troublingly, to imply that she needed to be raped to learn a lesson. A more fundamental problem is that expanding one character’s arc into a broad proclamation saddles the play with a burden it cannot sustain. Tessa’s story suggests one answer to the delicate, essential question of how to believe more women within a system that sends people to prison. Other stories—a woman locked up for defending herself against a man who tyrannized her, a man wrongfully convicted of rape—would suggest other answers. A one-woman show may not be the best vehicle for claims that put so much on the line. At least this play isn’t.