Anyone who is bothered by the marked absence of elephants from the woods and forests of America has only to turn to the pages of that great eighteenth-century naturalist, Buffon, to find the reason for this sad lacuna. Nature in America is less active, less varied, and less vigorous than in Europe because America is a new continent. Therefore the best it can manage in the line of pachyderms is the modest tapir. With time, perhaps, things may change—not that the tapir can ever hope to grow into an elephant, but at least those European breeds which, like the sheep and goat, have made the transatlantic crossing will no longer actually decrease in size in their new environment.

Buffon was a large man—a fact which may help to explain his predilection for the bigger animals as representing a higher level on the scale of creation. But within the large frame there dwelled a generous spirit, and when he moved from American quadrupeds to bipeds he treated the latter with relative moderation. The natives of America could not, of course, escape the general rule that governed the natural phenomena of the New World. “The savage is feeble and small in his organs of generation; he has neither body hair nor beard, and no ardour for the female of his kind. Although lighter than the European, on account of his habit of running more, he is nevertheless much less strong in body; …he lacks vivacity, and is lifeless in his soul.”

But Buffon was ready enough to leave the question there. Not so, however, the abbé Cornelius de Pauw. In his Recherches philosophiques sur les Américains of 1768, this querulous dogmatist, suitably fortified by the rationalism of the eighteenth century at its most irrational, was unwilling to allow the human inhabitants of the New World the benefits of Buffon’s doubts. For De Pauw the native American, so far from being an immature animal or an overgrown child, was a degenerate being; and this was because De Pauw’s America was not young but corrupt. In that debased environment only insects and reptiles prospered, and even these suffered from notable deficiencies, for “the American crocodiles and alligators have neither the impetuosity nor the fury of those of Africa.”

Not surprisingly De Pauw’s provocative assertions conjured up a storm of protest on both sides of the Atlantic. The virility of American men, the ardor of American women, the fecundity of American animals—all these became the subjects of furious and often erudite debate. Was America youthful or degenerate, innocent or corrupt? For the eccentric Lord Kames, South Carolina was the only exception to the general rule: “Europeans there die so fast that they have not time to degenerate.” For Benjamin West, on the other hand, a Mohawk was comparable to the Apollo Belvedere, while Thomas Jefferson assembled a formidable array of statistics to refute the pernicious thesis of American degeneracy.

This great American debate, which long outlasted its eighteenth-century proponents, and indeed has continued into our own times, if in a somewhat debased and diluted form, is the subject of Antonello Gerbi’s vast and fascinating book, The Dispute of the New World. A summary version of this first made its appearance in Spanish in 1943, but inflation then set in, and it re-emerged as an eight-hundred-page Italian volume in 1955. Now at last, updated and admirably translated by Dr. Jeremy Moyle, we have it in English; and none too soon, for this is a book which should be on the shelf of everyone who is curious not only about the European image of America but also about the history of man’s attitude to man. Dr. Gerbi’s study is a monument both to erudition and to fastidious wit; the outcome of years of reading and reflection by a historian of ideas who is at once playful and wise.

In method his book may have its defects, belonging as it does to the portmanteau school of intellectual history, which places comprehensiveness before selectivity. Indeed there are moments when the reader, plunged into yet another controversy between long-forgotten polemicists, is likely to feel that Dr. Gerbi has succumbed to Buffon’s notion that perfection is directly correlated to size. But as a volume to be sampled rather than read at a sitting, and as a compendium of strange ideas and erudite digressions, The Dispute of the New World is a triumph. Even if Dr. Gerbi himself is almost painfully aware of the research still to be undertaken and of the books he has not read, he has succeeded in writing a book that will never have to be written again. The feat is sufficiently rare to deserve an accolade.

But why should anyone bother with these six hundred tightly packed pages which set out to resurrect the often outrageous contributions of ill-informed dogmatists to a controversy that now appears as dead as the dodo? Apart from the insight they provide into some of the more startling vagaries of the human mind, there are at least two good reasons for taking the history of these often wild ideas more seriously than the ideas themselves. The first is the close relationship that existed, at some moments more than others, between attitudes and action. The second is the revelation of the degree to which Europe’s vision of America reflected and still reflects its vision of itself.

Advertisement

Dr. Gerbi begins his study with Buffon and De Pauw, although he allows himself a number of backward glances as he follows the great debate. But these backward glances are themselves sufficient to indicate that, even if the thesis of the “weakness” or “immaturity” of the Americas first acquired a scientific formulation in the eighteenth century, it belonged to a general European discussion about the nature of the New World and its inhabitants which stretched right back to Columbus and the moment of discovery. Gerbi himself quotes a revealing remark by Queen Isabella, who, on being informed by Columbus that the trees in the Indies did not have deep roots, was moved to reply that “this land, where the trees are not firmly rooted, must produce men of little truthfulness and less constancy.”

This remarkable regal pronouncement, which presumably derived from the environmental and climatic theories of classical antiquity, shows how Europeans tended from the beginning to see America with a double vision. On the one hand the New World was genuinely new—a veritable garden of Eden before the fall of man. Its inhabitants were innocent and uncorrupted beings, holding all things in common, and as yet unspoiled by the European vices of greed and litigation. On the other hand, the New World was a strange and treacherous world, whose trees had shallow roots, and whose peoples led primitive and barbarous lives, shamelessly exposing their nakedness, and eating reptiles and insects (or, still worse, each other).

This double vision proved to be of critical importance for the evolution of European attitudes to the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Arriving in the New World with their own stock of mental furniture and their inherited preconceptions, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europeans tended to see its inhabitants less as they were than as they expected them to be. And where reality did impinge, it often acted either to confirm prejudice or to encourage disappointment. If the native of the Americas was conceived of in advance as a noble savage, a closer acquaintance with the frequently shell-shocked victims of European conquest was liable to lead to disillusionment. If, on the other hand, the prior image was that of the ignoble savage, the very strangeness of native customs was liable to reinforce that image in culturally self-confident European minds. The image in turn provided a useful justification for European rule—as many settlers, and not least the promoters of the colonization of Virginia, were quick to grasp.

The Indians of North America must not be allowed to remain a “rude, barbarous and naked people,” but must instead be brought to (English-style) “civilitie.” This was the message that went forth from London in the 1620s, and provided a rationale for the efforts of the struggling colony. The story of these efforts has now been racily retold by Alden Vaughan in his American Genesis, which approaches them through a biographical account of Captain John Smith. Smith’s career, both before and after his arrival in America, is a colorful one, and Vaughan makes the most of it; but perhaps its greatest interest lies in watching how a man who had dealt in his time with Transylvanians and Tartars turned his rough expertise on the North American Indians.

Perhaps because he came to the New World with fewer illusions than most of his compatriots, Smith proved a tough and resourceful colonist. He had a proper respect for the Indians’ cunning and their warrior skills, but for him they were no more than dangerous adversaries, to be outwitted and subdued. He was impressed, as no Englishman could fail to be impressed, by the majestic figure of Powhatan, but showed not a trace of sympathetic understanding for the Indian way of life. The two worlds met in utter incomprehension when Smith attempted to get Powhatan to acknowledge his subjection to the English crown. “A foule trouble there was,” wrote Smith, “to make him kneele to receive his Crowne, he neither knowing the majesty nor meaning of a Crowne, nor bending of the knee….” What clearer indication of total barbarism?

The precariously stable relationship which Smith temporarily succeeded in establishing between the colonists and the Indians was a relationship based on fear; and, as such, a pattern for all too many of the relationships between the European and the non-European world. But, fortunately for the record, the story of Europe’s overseas conquests is not exclusively defined by arrogance. Alongside the arrogance there has run a strain of guilt, which has consistently prevented the uncritical acceptance of what was done by Europeans in the name of civility and of Christianity. Against the cry of superiority has run the counter-cry of conscience, and nowhere was this cry more powerfully uttered than in the Hispanic world of the sixteenth century.

Advertisement

Ever since 1597, when the Mexican archbishop of Santo Domingo praised Bartolomé de Las Casas as “the apostle of the Indians,” the great Spanish Dominican has stood as a symbol of Europe’s uneasiness at its own colonial record. It is hardly surprising that the twentieth century, profoundly preoccupied with imperialism and the problems of decolonization, should have produced an immense concentration of studies on the words and works of Las Casas.

Here, after all, was one of the first Europeans to experience in his relations with non-Europeans that crisis of conscience that was to affect so many others down the course of the centuries. Arriving in Hispaniola in 1502 from his native Seville as a priest who was supposed to promote the Christianization of the natives, he soon became more interested in his agricultural and mining enterprises than in the religious instruction of his flock. But in 1514, after being denied absolution, he found his road to Damascus, and underwent a conversion experience which led him to join the Dominican order and devote his remaining fifty-two years to crusading on behalf of the oppressed Indians of America.

In letter and in person he pressed his case tirelessly at the court of Charles V and Philip II; he obtained permission to undertake a peaceful colonizing project, which proved a fiasco; he aroused the bitter hostility of the Spanish colonists, both as bishop of Chiapas and as a lobbyist in Spain, by his attempts to prevent the exploitation of the Indians and secure legislation to improve their well-being; and he produced some eighty writings—some of them extremely voluminous—to publicize his cause. The passionate commitment, the gift for publicity, the skill in exercising pressure on a vacillating government—all these make the great Dominican very much a figure for our times. If conquistadors like Cortés and Pizarro were the heroes of the imperialist Europe of the nineteenth century, Las Casas could hardly fail to be the hero of the anti-imperialist Europe of the twentieth.

The Northern Illinois University Press has now swollen the rapidly expanding library of Lascasiana with three handsomely produced volumes in identical format. The first of these, which appeared in 1971, is a large volume of essays by different hands, entitled Bartolomé de Las Casas in History. This is an intelligent compilation by two noted historians of Spanish America, Juan Friede and Benjamin Keen, of studies of different aspects of Las Casas’s life and thought, most of them specially commissioned for the occasion. To those who already know the work of such great Las Casas scholars as Marcel Bataillon and Manuel Giménez Fernández (who passionately and somewhat incongruously identified Ferdinand the Catholic and his officials with Franco and his henchmen), the volume will contain few surprises. But it usefully presents the English-speaking reader with a summary of the present state of thinking and research about this formidable and most complex defender of the non-European against European domination.

Las Casas’s energy in pursuit of a cause was proverbial, his life was long, and his literary production almost overwhelming. Anyone who plunges into this great waterfall of words needs at least a touch of the crusading fervor, and the stamina, of Las Casas himself. Fortunately neither has been found wanting in that great American doyen of Las Casas studies, Professor Lewis Hanke, who has done more than anyone else in this century to make the “apostle of the Indians” known to the Anglo-Saxon world. Hanke has been a stout champion of Las Casas both in season and out of season, intrepidly defending his hero from the slings and arrows of his fellow historians, and from the thunderbolts hurled by Spaniards of the right against the great betrayer of their national ideal. Now, in All Mankind Is One, which he alleges is positively his last pronouncement on Las Casas before turning his unabated energies to other Spanish-American fields, he has the satisfaction of introducing and summarizing the last known major work of Las Casas to have remained unpublished.

This work, In Defense of the Indians, which has been translated from the surviving Latin manuscript into English by the Reverend Stafford Poole, is of the greatest historical interest because of the circumstances in which it was produced. In 1550, in one of the most remarkable episodes in the history of European colonization, the Emperor Charles V ordered that all conquests in the New World should be suspended until a verdict had been reached by a group of theologians and royal officials on the methods and merits of conquest. The case for and against the use of armed force against the indigenous peoples of America was put, respectively, by Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda and Bartolomé de Las Casas.

On the first day Sepúlveda spoke for three hours, summarizing his treatise, the Demócrates Segundo, which only found its way into print in the late nineteenth century. On the second day the seventy-six-year-old Las Casas characteristically launched into a public reading of every word of his monumental In Defense of the Indians—a process which went on for five days, no doubt to the exhaustion of the judges. These may be forgiven for asking one of their number to provide them with a summary, and it is this summary by De Soto that has had to stand as the expression of Las Casas’s side of the argument until the present publication of the original treatise.

It must be confessed that anyone who picks up In Defense of the Indians in the hope of rapid enlightenment is likely to feel the deepest sympathy for the unfortunate judges. Las Casas never used one word where he could use three, and he batters away at his opponents with more vigor than finesse. And yet what a superb vindication of an oppressed people Las Casas managed to produce! Couched in the language of scholastic controversy, its method and its content inevitably seem alien and remote to the modern reader. But the message shines through, and now and again a vivid phrase comes ringing down the centuries. “Men want to be taught, not forced.” “Has an Indian ever received a benefit from a Spaniard?”

At least to our eyes the moral victory lies with Las Casas. But to the judges the issue seems to have been less clear-cut. The debate apparently ended in a draw, and no formal verdict was ever returned. Some of the principles for which Las Casas had fought with such determination were, however, embodied in the ordinance promulgated by Philip II in 1573 to regulate new conquests. But it was one of the great tragedies of Hispanic colonization that theory and practice were always poles apart.

Although the debate was superficially concerned with the justice of military conquest, in reality it presented two opposing views of the native peoples of America. Sepúlveda, employing Aristotelian arguments, was attempting to justify European domination on the grounds of the natural inferiority of the Indian. Las Casas, operating within the same intellectual frame, was attempting to prove from his first-hand knowledge of the New World and its peoples that they were neither bestial nor barbarous. In the circumstances, it is not surprising that Sepúlveda should have been hailed as a hero by the colonists—or, for that matter, that Las Casas should at certain moments of his career have won the sympathetic attention of an emperor deeply concerned to prevent the establishment of a New World feudalism by the settler community. The ideas of both the great protagonists, however theoretical their presentation, were in fact intimately related to the problems of colonial rule and to the American reality.

This great Valladolid debate of the mid-sixteenth century was in reality the precursor of Dr. Gerbi’s great debate of the mid-eighteenth century. In both debates the same themes recur—childishness and barbarism, degeneracy and innocence. The size and strength of the American Indian were as much matters of dispute for Las Casas and Sepúlveda as for Jefferson and De Pauw. And in both instances the debate was passionate because Europe, even more than America, was being put on trial. America, more than any other continent, was Europe’s own creation. As such, it was bound to reflect in a very special way the hopes, the ambitions, and the disappointments of those who had created it. Had Europe made America, or destroyed it? Or a bit of both? With what justification, and to whose benefit, had it killed and colonized? Was Europe Captain John Smith, armed with all the self-righteousness of cultural and ethnic superiority? Or was it Bartolomé de Las Casas, deeply troubled by the awareness of a collective guilt? Or, again, was it after all perhaps a bit of both?

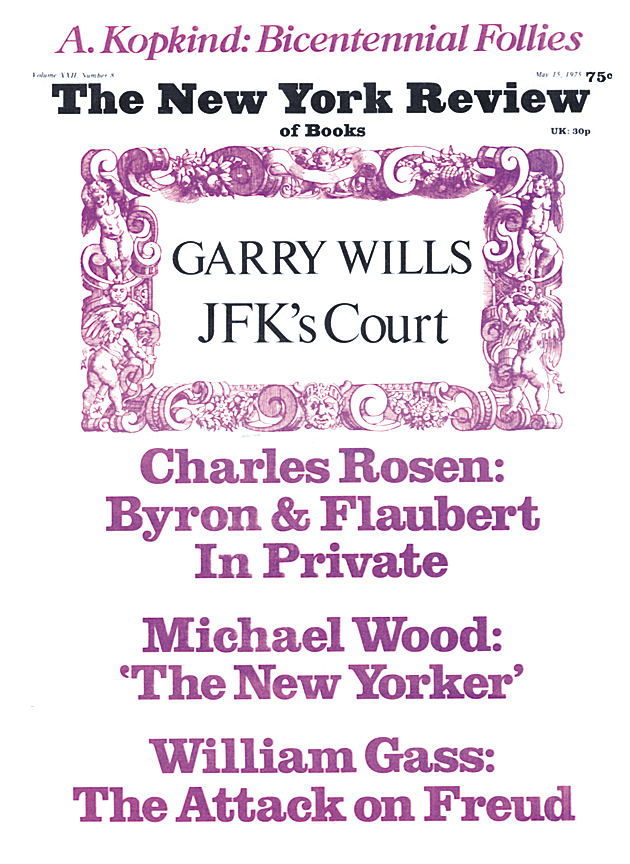

This Issue

May 15, 1975