Perhaps it takes an Irishman to offer Englishmen (and others) a convincing picture of the religion of the ordinary lay people of England in the age before the Reformation. Over four hundred years following the Elizabethan settlement the established Anglican church developed traditions of worship and practice, focused around the Book of Common Prayer, which became the core of the religious observance and experience of English parishes, a way of church life which their people, at varying levels of individual religiosity, learned to accept as natural. For them, and for British historians born of their stock, the Anglican way became what Eamon Duffy calls their “traditional religion.” Medieval Roman Catholicism, the outwardly very different “tradition” in religion, with a thousand-year history behind it, became difficult to remember, and harder still to relate to sympathetically. The evocation of that older, pre-Reformation tradition and of what its observances meant to the laity of its time is the theme of the first part of Dr. Duffy’s deeply imaginative, movingly written, and splendidly illustrated study.

That first part of the book is presented thematically, under four main sections, devoted respectively to the liturgy and the learning of the laity, their experience of the Holy, their modes of prayer, and their attitude to the deathbed passage from this world to the next. Following the revisionist lead of such scholars as J. J. Scarisbrick and John Bossy, Duffy gives here a highly positive account of the dynamism of the practices, observance, and prayer life of the “old religion” up to the very eve of the Reformation. He firmly rejects the traditional Protestant picture of a laity whose confidence in a corrupt and ignorant clergy and its excessive sacerdotal claims was already by that time undermined.

The second part of his book is devoted to the quest for an answer to the question that becomes pressing if this positive account is accepted: How was it that the new ways, ushered in during the decades following Henry VIII’s political breach with Rome, came to be accepted so widely, and with so little protest? Here Duffy’s approach becomes predominantly a narrative one, as it has to do. There is no other way by which the tale of the bitter, politically and theologically driven, attack on time-honored rituals and on objects of beauty—rood screens, images, paintings, sculptures—can be told, or the progress of its success charted. The title of Duffy’s book, The Stripping of the Altars, relates its two halves skillfully. The first thematic part explains why the stripping was such a mammoth task; the second how nevertheless it succeeded, and not just in its negative iconoclastic aim but in founding a new tradition that came in time to be loved as the old one had been. The story is a poignant one; it is a credit to the author’s historical integrity that he does not let that poignancy, which he clearly feels deeply, run away with his judgment.

In recent years, historians have laid much emphasis on the personal aspects of lay piety in the late Middle Ages; on its inward looking, affective quality; on the proliferation of licenses to the noble and genteel to build private chapels and to have their private confessors; on the fashion for devotional reading in the household, often of contemplative works in the vernacular. Duffy does not question the significance of these trends, but in the first part of his book he puts his own prime emphasis firmly on the communal aspects of religion, on the parish church, and on the liturgy that provided the backbone of its observance. The relation of the liturgical calendar to turning points in secular time—Christmas at midwinter, Easter in spring, Our Lady’s feast at harvest, Michaelmas and All Saints in the fall of the year—helped to promote a delicate and elaborate interweaving of worldly and otherworldly concerns in rituals and processions; the plow ceremonies on the first working day after Christmas are a good example. In this case no doubt there was a fertility rite somewhere in the background. But the proliferation and popularity of new feasts, such as Corpus Christi and, later, the Holy Name of Jesus, which had no very definable place in the round of the seasons, should caution historians against over-stressing the secular element in the interrelation of liturgy and calendar. We are dealing with genuinely religious not just traditional observance.

The most elaborate of all rituals were those of Holy Week, whose vivid ceremonies affirmed the place of the Passion at the heart of medieval Christianity. On Palm Sunday “palms” were distributed (actually branches of yew, willow, or box), and the Host was carried in procession to a cross in the churchyard before the Mass commenced; on Maundy Thursday the altars were stripped after Mass of their ornamental coverings, recalling the parting of Christ’s garments at the Passion; on Good Friday clergy and people assembled in church and crept barefoot on their knees to kiss the foot of a cross held aloft by two ministers, which after Mass was “buried” in a “sepulcher” on the north side of the chancel, together with a consecrated Host representing Christ’s body. On Easter Sunday all the lights of the church were lit, the Host was carried to the pyx above the High Altar, the cross raised from the sepulcher and carried to another altar, when the people once again crept to venerate it.

Advertisement

The liturgy of the pre-Reformation church was a Latin liturgy; part of the purpose of dramatic ceremony such as this was exegetical and instructional, to bring home the story and meaning of the feast celebrated to lay people who could not comprehend, word by word, the gospels, collects, and antiphons of the rite they were following. Drama was in these circumstances a natural adjunct of worship and religious instruction, and not only where there was a story to be told; the Paternoster Gild at York presented annually a play “setting forth the goodness of the Lord’s Prayer,” and the Corpus Christi Gild a Creed play in twelve pageants (forgiveness of sins, for instance, could be portrayed dramatically through the incident of Christ and the woman taken in adultery).

There were countless parallel ways in which the same ends could be achieved; gospel history, the Ten Commandments, the virtues and vices, or the seven works of mercy could all be as well illustrated in the “still life” of stained glass, sculpture, or wall painting as they could through drama. The great crucifix, or rood, above the screen that in every church divided chancel from nave and before which a light burned perpetually, proclaimed to all the centrality of the Passion and Christ’s atoning death. The sculptures and the figures of the saints painted on the panels of the rood screen reminded worshipers of the communion of the saints and of that wider communion between the living and the dead in Christ, in which the saints were their neighbors and helpers.

We find something of the same sort in the Primers or Books of Hours, the private prayer books of an increasingly literate laity, which the early printers, such as Caxton and Wynkyn de Worde, mass-produced to meet what was clearly an enormous demand and to which Duffy devotes close attention. Centered around the Little Office, the Hours of the Virgin of monastic observance, these books were in Latin, but the woodcut made it possible to produce abundantly illustrated primers at moderate prices, with devotional images matched to appropriate prayers and texts—and they sold abundantly. Most primers contained other material besides the hours, including vernacular para-phrases of rites and texts (often in verse) and prayers; to judge by what the printers provided there was an increasing demand in the early sixteenth century for such vernacular material.

The primers apart, there was a growing body of religious writing in English available to the laity, ranging from meditative works like the widely read Mirrour of the Blessed Lyfe of Jesu to catechetical treatises like the Arte or Crafte to Lyve Well, printed in 1505 by Wynkyn de Worde with profuse illustrations, depicting for instance Jesus teaching the apostles to pray (below its version of the Lord’s Prayer), Moses and Aaron by the Ten Commandments, the seven deadly sins with pictures of punishments fitting the crime. Vernacular literacy, we see, did not eliminate the demand for illustrations that would stimulate meditative or confessional reflection in traditional mode. No more did it devalue the esteem in which the Latin of the Sarum rite was held; the words of scripture and of the liturgy came from God, and were words of power, in a language perceived as higher and holier than the vernacular.

The popularity of the primers, the vogue of new feasts and cults such as those of the Holy Name or of the Five Wounds of Christ, together with the continuing centrality of the parish Mass and its ceremonies, and the sense (frequently attested in religious writing) of the blessing that flowed from the sight of the elevated Host, all affirm the hold on the people of traditional religion at the eve of the Reformation. Perhaps most striking of all in this context, given the subsequent Protestant rejection of traditional teaching about Purgatory, is the attitude of the laity to death and the hour of its coming.

As Duffy stresses, the historian needs to be careful not to exaggerate the morbidity of the pervasive emphasis on memento mori in the Christian culture of the late Middle Ages. Depictions of the danse macabre and the gross physicality of cadaver tombs, with their sculptured flesh rotting on the skeleton, had a positive spiritual purpose, “to bring home to the spectator the reality of his own mortality, and thereby to bring him to a sense of the urgency of his need for conversion.” Prayers for the dead were an effective expression of the kinship between the living community and that of those who had gone before, of their unity within the framework of salvation.

Advertisement

There was indeed much more than the individual “purchase of paradise” to funerary processions, to the countless and lavish bequests for lights to be lit on the day of passing and its anniversaries, to the expensive endowment of chantries and of masses for the departed, to funeral doles and charitable bequests that associated a testator’s last wishes with the acts of mercy. But there seems little room to question the hold of the contemporary beliefs about the life beyond the grave, about the pains of Purgatory, about the value of intercession and of indulgences. Purgatorial and associated beliefs colored the whole culture of pre-Reformation Christianity from its view of confession, of penance, and of the role of the saints as intercessors down to the very physical layout and furnishing of the churches in which people worshiped. The priest’s role at the deathbed of the faithful is for that reason one of the surest signs of the high esteem in which sacerdotal powers were held in the lay mind.

How was it, then, that, between 1530 and 1580, so much was swept away with relatively so little protest—and swept away brutally, with the destruction of images, the dismantling of rood screens, the banning of lights and ceremonies such as creeping to the cross, and the discontinuance of masses for the dead, the whitewashing of wall paintings, the “stripping of the altars”? The essence of Duffy’s explanation here rests on an amplification and substantial enlargement of the point that others such as Scarisbrick have stressed, that the English Reformation was a political Reformation, set off by a king’s need to deny Roman supremacy in order to obtain a divorce. It was directed from the top. There was an important theological side to it, of course; its ecclesiastical leaders, such bishops as Cranmer, Ridley, and Latimer, and their educated lay sympathizers in the circles of the Boleyns and of Thomas Cromwell, were religiously indignant at what they had come to see as the superstition, bordering on necromancy, inherent in traditional observance. They deplored the “idolatry” of “image worship,” the “false miracle” of transubstantiation, all that seemed to suggest a belief that human words and sacerdotal actions could direct the operation of God’s omnipotence.

Often they would have liked to move faster than the royal authority on which they relied would permit. Henry VIII’s theological conservatism, the uncertainties of Edward VI’s reign, and, later, Elizabeth’s unwillingness to “make windows into men’s souls” drew out the process of stripping the old and substituting the new. But when and as authority permitted, the reformers were able to strike, with the threat of severe penalties in the background, at just where traditional religion was most vulnerable, at its externals—at the church furniture of images, at books and vestments, and at the ceremony and pageantry of public observance and procession.

The reformers’ principal weapons were the Injunction and the Visitation. The injunctions backed by royal authority set the pace. Those of 1538 forbade for instance the burning of lights before images, condemned pilgrimages, and silenced the Angelus bell; those of 1547 ordered the removal from churches of all relics, images, and paintings as “monuments of feigned miracles, idolatry and superstition,” and banned parish processions. The visitations, parish by parish, carried out by bishops and their officials, made sure that each and every injunction had been obeyed. These visits offered protestant zealots the opportunity to push things, at the local level, a little further than the injunctions, strictly read, might seem to order. New protestant primers, with a monopoly of royal authorization, replaced the old; it was out of these that the Book of Common Prayer evolved.

In face of this onslaught, as Duffy eloquently explains, there was little parish priests and churchwardens, ordinary people with no wish to make martyrs of themselves or their neighbors, could do to resist. The orders came from above, and disobedience was likely to prove disadvantageous, if not dangerous. Of course there were protests, the Pilgrimage of Grace and the “Prayer Book” rebellion of 1549. By reminding the secular power of the political wisdom of soft-pedaling reforms they probably only made the triumph of the process the surer in the long run. It is significant that the authorities of Mary Tudor’s reign, in their attempt to reverse the process and reinstall Roman Catholicism, used precisely the same weapons: command and visitation. Duffy believes that, given time, these would have surely had effect as ultimately, after Elizabeth’s accession, protestant injunctions and scrutiny did.

Injunctions, of course, could not change hearts, only enforce outward acquiescence. As Duffy makes clear with a wealth of reference, there were many whose reactions surely if undramatically revealed their dismay at the assault on traditional ways, on imagery and ceremony with which they were affectionately familiar through long use. When the reaction came under Mary images that men had taken to their homes or hidden, vestments that they had bought at low prices when they were forcibly sold, paraphernalia of private chapels that had been lent to the parish and reclaimed ahead of visitations, were brought out again to refurbish the old rites now restored. Testators went back to invoking the Virgin and the saints in the preambles to their wills, where a few years before they would have avoided mentioning them lest this should lead to the questioning of the will itself, which had to be proved in the episcopal court.

The puritan complaint in 1584 that “three parts at least of the people” were still “wedded to their old superstition” was probably an accurate perception. But time, as well as authority, was on the side of reform. In 1584 a man needed to be nearly seventy to remember clearly the days when old ways had seemed securely traditional. In the meantime the resonances of the English prose of Cranmer’s prayer books and of the Great Bible’s translation of scripture had been nursing new loyalties, which aided the development over time of a new Anglican angle of vision on what the beauty of holiness could mean.

Eamon Duffy’s analysis, in his richly detailed book, of what happened at the Reformation to the religion of the laity of England for me carries conviction. It rests heavily on his assumption that pragmatism was a governing consideration in the ecclesiastical conduct of Tudor lay folk; that, reluctant as they may have been, they saw the wisdom of bowing to royal injunctions with power behind them in matters of externals—and so bowed, putting aside their often real nostalgia for old ways. This seems a sure perception about the way that lay folk are likely to react in the face of orders about the externals of their religion.

Ironically, this is at the same time the grounds for my single reservation about this splendid study, which concerns not its conclusions but its balance. So vivid is Duffy’s evocation of the traditional religion of the laity of the pre-Reformation age and so sensitive is he in his empathy with their piety that it is easy to mistake him to be implying that the English people of the fifteenth century were somehow more pious and less pragmatic than their Tudor descendants. Of course they were not. As anyone who has had any scholarly acquaintance with their secular dealings with one another knows well, they were as practical and worldly as any other generation. As William Langland wrote in Richard II’s reign, “The most part of the people who live and die on this earth find all that they value in this world and desire no better; they have no thought of another heaven.” If the world beyond the grave had not been to the men of his day, just as much as to those of Shakespeare’s, “an undiscovered country,” the protestant attack on the purgatorial belief that colored so much of late medieval religion could not have carried so much before it as easily as it did.

Duffy says a little too much for a strictly even balance about the heart-warming aspects of the piety of the late medieval age, too little of its coolnesses. He says a little too much about the heart-chilling aspects of reform, and too little about the new insights of the reformers. But that slight imbalance is only a consequence of the range and originality of his book; he has concentrated on the things that most need saying. We protestants (I speak for myself here) do need reminding from time to time that Chesterton’s indignant cry against the sixteenth-century reform, “And Christian hateth Mary that God kissed in Galilee,” has more to it than Edwardian religious neo-Romanticism; it contains an uncomfortably accurate historical perception.

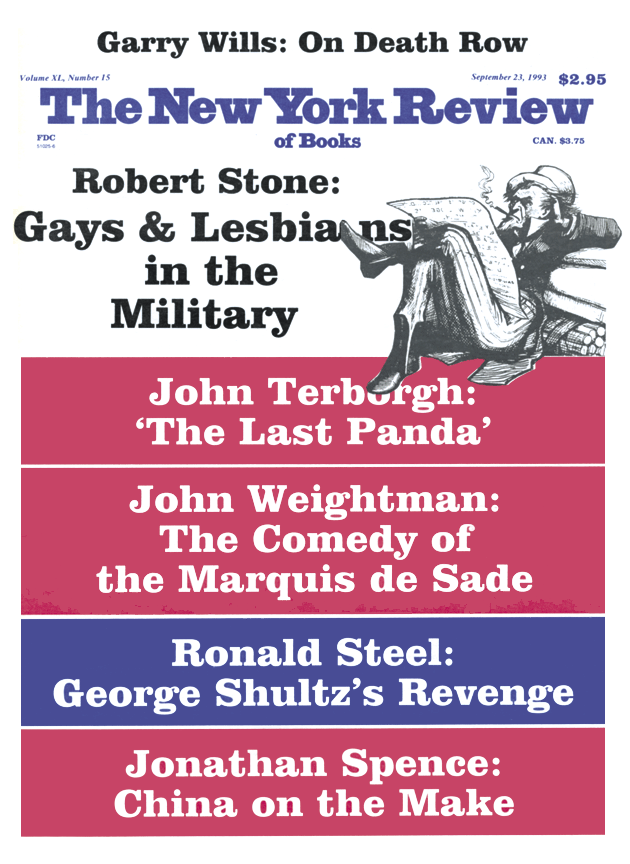

This Issue

September 23, 1993