Memory, that dubiously reliable prompter, persuades me that when first I sighted the child Qubilah Shabazz, she was a baby on television and her father was cradling her against his chest with a right arm as soft as his tongue was hard. It was early in the Sixties and Mr. Malcolm’s family had come to greet his return from abroad home to Babylon. The journalists were having at him to comment on an unverified report of the kidnapping of white settlers in the Congo. Mr. Malcolm was replying to the general effect that he knew of nothing that had happened to these people and that, if anything untoward had, he was confident that they must have asked for it. Each of his words froze to ice on the spot; and all the while this enchanting infant sat and smiled in the comfort, the warmth, and the peace of his restored embrace.

While I could not suspect him of using Qubilah as a prop, I would fairly have excused him if he had. Malcolm X’s special genius was for preserving his message intact in the prison of the sound bite. He was one of those complicated men in whom nature has mixed the tender with the fierce; and he was conscripted to conveying the whole of that mystery within thirty seconds. And there on the screen before strangers, he and his daughter had brought it off with the warmth of her face to express his tender side and the coldness of his voice to summon the ferocity that duty commands for an ambassador from another and alienated shore.

Mrs. Malcolm did not bring her daughters along when she came to criminal court to testify in the 1966 trial of the three men who had been indicted for his murder. She made a most majestic presence but no very useful witness, because she had been too occupied with settling her children into their portion of the Audubon Ballroom’s balcony to notice the approaching horror upon its stage. On her dismissal, she commenced an erectly regal progress toward the door and then paused beside the defense table as though she needed to collect herself.

A court officer offered his help and she declined it and simply said, almost as if to apologize, “They killed my husband.” Defense counsel protested and the late Justice Charles Marks replied that he hadn’t heard anything. He would have to have been as deaf as the bench upon which he sat not to have heard words whose echoes were still resounding from the walls of the court-room like the aftercrash of the Hammer of God. I am too unfamiliar with queens to know whether they die proudly, but I am convinced on the evidence of this, the only one ever accessible to my observation, that they can destroy totally and never abate the stateliness of their bearing when they do.

The defendants were found guilty, and thanks to Justice Marks’s temporary disability, the terrible blow Mrs. Shabazz had dealt them went unrecorded in the trial transcript, and the appellate division was spared what might have been a bump on its easy road to affirming their conviction.

Mrs. Shabazz was delivered shortly after of twins, and raised all her girls by herself with sufficient reserves of energy to earn her doctorate and to send them off to the suns and storms of the grown-ups’ world. She never lost her certainty that she had been widowed by servants of Elijah Muhammad. Those who have been there are the least disposed to entertain theories of grand conspiracy, because they understand that the conspiracies that make for tragedies like theirs are only too often the petty doing of people they know.

It cannot yet be said whether or not Qubilah Shabazz hated Louis Farrakhan enough to scheme upon his murder. But every degree of hatred short of vengeance in blood deserves a full pardon for any wife or child of Mr. Malcolm’s who may have felt it. Farrakhan qualifies as hateful not because he may have contrived Mr. Malcolm’s assassination but because he so shamelessly and thoroughly enjoyed it then and even now.

Once in a while he will repair for absolution to one of those television confession boxes and come as close to penitence as may be said to show itself when conceding that his savage cries for Mr. Malcolm’s head may have been a lapse from the proprieties of public discourse. But set him before his flock and it becomes his delight to flourish what he takes to be Mr. Malcolm’s condign punishment as a cautionary exhibit for such of the faithful as might be straying toward heresy.

He is the enemy who insists upon reminding you of the wound he inflicted; and to conceive of this creature preening and swelling over and over on the Shabazz television set is to sense protractedly cruel violations of the Shabazz home.

Advertisement

Qubilah Shabazz might have given way to the hatred that Farrakhan so persists in rousing and re-rousing; but, if she did, it is unlikely that she would have been stirred toward action without the dosages of stimuli and urgements dealt her for six months by a para-agent for the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Farrakhan will no doubt torment the Shabazzes from here to the grave; but mightn’t these cops cease their afflictions? The New York Police Department assigned a guard patrol to Malcolm X’s meetings and then withdrew it to a place three blocks away from the final one, which their own undercover operatives had warned them could be fatal. The only plausible explanation for this display of willed indifference is that, when one perceived set of nuisances is disposed to relieve the cops of another, it is politic to let them both be. Police work is boring and policemen need a bit of sport. In this instance, the FBI’s taste for such appears to have been of the low order that has fun playing at the transformation of a justifiably aggrieved young woman into a shopper for a contract killing.

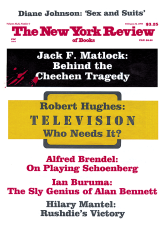

This Issue

February 16, 1995