Since the theme of Evita is fame, it’s worth noting that during the early Thirties, when Eva Duarte was a skinny, sickly young outcast living on the Argentine pampas, the two consolations in her life were reciting florid poems about death and buying a fan magazine for the glamorous stills and the news that it brought of her favorite Hollywood actress. From our late-century perspective, her choice, Norma Shearer, looks odd. Today we easily remember actresses who came along just two or three years later. Bette Davis, Barbara Stanwyck: we remember their fierceness, their elegantly hunched posture, the way they wore chorus-girl shorts or antebellum gowns. Compared with them Evita’s heroine seems like something primordial, a one-cell precursor of the real stars who were about to arrive.

What did Evita respond to? Norma Shearer was versatile, hard-working: she could play drawing-room wits, tough divorcées, even Shakespeare’s Juliet. Several biographies mention that Evita especially loved the costume epic Marie Antoinette; it was just the kind of grandiose, tear-jerking part she would take on a few years later, in an Argentine radio series on Great Women of History.1 And then there’s the suggestive fact that Shearer was married to Irving Thalberg, the enigmatic “genius” president of MGM, who used his pull to get his wife studio billing as “First Lady of the Screen”; perhaps the young Evita already sensed the benefits of marrying power.

Still, without being exactly plain, Shearer was short, with humdrum brown hair and a squint, and she didn’t carry a strong personality from film to film. To single her out for worship, you would probably have to believe that fame and success beget greatness, and not the other way around. If you were young and ambitious and your own life was painful to contemplate, you might overlook a certain blankness, an utter lack of introspection, that special quality defined by Lillian Hellman as “mind unclouded by thought.”

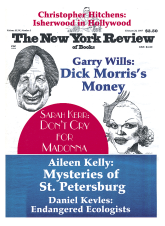

Shearer’s star faded away. But her dogged spirit, such as it was, survives. Consider the promotional campaign for the new movie Evita, which led off in November when Madonna posed for the covers of Vogue and Vanity Fair. One was first struck in the photographs by the absence of bustiers, provocatively positioned crosses, and otherwise suggestive dress we had come to expect from Madonna. She wore elegant tailored 1940s suits and hats, and she pulled her hair back in Evita’s austere signature chignon. She also wore brown contact lenses, which aided her effort to resemble Evita but gave her face a vaguely nonhuman, mannequin sheen. Both magazine covers mentioned the fact of her new motherhood (Vanity Fair promised “Private Diaries” inside and spoke of “dreams and heartache”), but she did not look ready to confide warmly. She did look slightly tired, almost enough to make you wonder whether a real person was bursting out. But in fact the fatigue seemed more a message that while she was tired she wanted to show us how hard she was working.

Hard work has been the movie’s selling point. Evita has arrived with the astonishingly well-coordinated efforts of publishers and the press and the fashion world (magazine covers, new books, a Christian Dior revival, a line of cosmetics from Estee Lauder). It also arrives with pained reports on the number of directors (ten) proposed over the years and the parade of stars (sixteen, from Charo to Meryl Streep) who at some point nearly signed to play the title role. But these stories fold into the actual story of the driven yet suffering heroine to create a larger fable about surmounting obstacles. The movie even takes spiritual authority from them, as if this project, like a Gothic cathedral, couldn’t have been rushed.

And because at a minimum great effort can be an affecting thing, I went to see Evita as a skeptic, but was also prepared to be moved. Which is lucky: the movie opens at the exact moment of the heroine’s death, 8:25 PM, July 26, 1952, and within seconds it asks us to grieve.

The heartstring-puller here at the start is Andrew Lloyd Webber’s music. He composed it for the stage twenty years ago and it still reflects the cynical-maudlin mood of the post-Watergate years-sadness stemming from the corrosive sense that everything is a hoax, and an eagerness to flout authority. A pretty choral requiem echoes English liturgical music, but strips it of God, retaining the yearning quality of a rock ballad. A dirge theme is suddenly interrupted by a guitar, which is played with the exaggerated vibrato style favored, briefly and long ago, by Eric Clapton.

The soundtrack is as dated in its own way as Doris Day, and it bears little relation to the sober, hardworking Madonna that has been advertised. But while it goes on something else is happening on screen, something that isn’t a leftover from the stage play: in a montage of mourning, the city, Buenos Aires, 1952, is recreated inch by inch. In his introductory essay to a book of still photographs from the film, the director, Alan Parker, describes his preparation for the funeral scene:

Advertisement

We had analyzed the documentary footage of the actual mammoth event and were anxious to replicate it down to the smallest details…. The call sheet read as follows: 4,000 crowd to include: 50 mounted police, plus horses; 200 soldiers; 50 army officers; 50 foot police; 60 sailors; 60 nurses; 300 working-class women; 100 upper-class women; 51 descamisados; 20 naval officers; 12 naval police, 300 working-class men; 15 palace guards; 8 pallbearers; 60 navy cadets; 60 army cadets; 300 middle-class women; 300 middle-class men; 100 aristo men; 100 boys; 100 girls; 200 male background; 200 female background; 1,400 miscellaneous background; gun carriage; coffin; 4 army motorcycles; 2 police motorcycles; 6 Bren carriers; 2 half-track military vehicles; 2 fox tanks; 4 army trucks; CGT float, etc. etc.

Twenty years ago the Argentines banned the musical, and many of them were afraid that the movie would play with the facts of Evita’s life. But in Alan Parker, they have an obsessive worthy of their obsession. 2

History is not a problem: all the central episodes are here, and in general they are not played for scandal. (The song that comes closest to controversy, “And the Money Kept Rolling In (And Out),” is about the financial workings of a charitable foundation.) In a scene intercut with Evita’s funeral, we see a tearful seven-year-old Evita trying to get into her father’s funeral but rebuffed by the father’s smug legal wife, because she and her siblings are illegitimate-a humiliation that forever sealed her “sense of outrage against injustice.” Madonna becomes Evita at fifteen. We watch her leave the town of Junín for Buenos Aires and scramble to fame, and although the film perpetuates unproven rumors that she slept her way into magazine layouts, shows, sponsorship by a soap company, and every job on up to First Lady, the sequence that shows this is clinical, perfunctory, and basically sympathetic. The June 4 revolution, a revolving-door coup that went through three presidents in one day, enabling Perón to take power, is efficiently rendered. So is his quick response to an earthquake in the Andean town of San Juan, which boosted his popularity and introduced him, at a benefit for the victims, to Evita.

Musicals usually take place against an abstracted backdrop so as to magnify feelings-the girl’s longing for her lover, the jealous man’s rage. Evita does the reverse. It is still entirely sung, as it was on stage, but because Parker wanted a naturalistic effect, the music was taped in London, and the film was later shot in Argentina (and Hungary for a few scenes) to a pre-recorded playback. Not surprisingly, this results in exquisite dubbing and somewhat canned performances.

Adding to the remoteness is the handling of the second male lead, after Perón. In the 1978 original, apparently at the insistence of the director, Hal Prince, Che was explicitly the Argentine-born guerrilla leader, Che Guevara. He walked onstage with his beret and rifle to comment on Evita’s progress as she begins to rally workers and women and trades her vulgar-actress dress for Christian Dior and jewels.3

For the film version, Che is still a theatrical device, a one-man chorus. He still points out Evita’s maniacal ambition,but also suggests a tenderness for her beneath his hard, didactic shell. But Parker turns him into more of a narrator, cutting away to scenes around Buenos Aires to give a sense of social conditions in 1940s Argentina: the arrogance of the army; the morbidity and prissy selfishness of Perón’s enemies in the aristocracy; the energy of Perón’s supporters, the olive-skinned peasants and immigrants who swept into Buenos Aires in the first part of the century; the sinister readiness of all sides to commit violence. More important, in the movie Che has dropped his last name and become-this phrase appears in Parker’s essay and in the press kit that Disney sent out, as if the description were the result of a committee meeting-Che, the “Brechtian everyman.” In mob scenes this new chameleon Che is a virile, dishevelled worker, but when the camera pans across a polo match he’s a dandy dressed in white linen.

Again, the theatrical crudity of the original is avoided-what we get instead is a numbing literal-mindedness, as if this were a sung newsreel. To be fair, Tim Rice’s lyrics already paved part of the way: “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina,” the famously beautiful song that Evita sings to a crowd outside the presidential palace, aspires to the pathos and hummability of Puccini, but the words are about one person’s relationship to abstract millions. Still, the stage play was written in an era when politics was considered a razzle-dazzle game like show business; it combined flippancy with the sad Bohème-ian twist of Evita’s early death to create a camp tragedy.

Advertisement

The movie is even-keeled, grim. It is a story about ambition and fame told by people who take these things very seriously.4 But it doesn’t bother to show us the star rising to stardom on her special, unique energy, because it assumes what the stage play could not. It assumes that we already care about Evita because we’ve heard so much about her-because, historically speaking, the play already made her a star. So after all the painstaking verisimilitude the movie neglects its characters. Evita the woman shrinks. It’s the background we react to-especially the crowd, with its power to applaud or boo.

The impulse to fall back on the story of how people responded to Evita is easy to understand, because her own personality was so amorphous and her story is shot through with holes. Anti-Peronists slandered her, and she herself was not above lying. Also, her emotional, paranoid rhetoric, for example this radio speech from 1944, did not invite analysis:

The Revolution did not come without reason. It came because something painful and hard had grown in the country, deep down where there is hate and passion and the sense of the injustice that makes the blood rush to one’s hands and head.

Even the biographies, in trying to puzzle out who Evita was-the latest is Eva Perón by Alicia Dujovne Ortiz-tend to get lost speculating over the truth or untruth of hearsay, concentrating on what is difficult to know: Did she actively aid Nazis in Argentina or was she just complacently acquainted with a few of them? Did her political convictions extend beyond a furious identification with the downtrodden? Why, after the Rainbow Tour of 1947-her glorious trip to the Continent, where she glittered like a queen, giddily throwing money at crowds of people devastated by the war-why after this triumph did she seem altered, more sober, ready to get down to hard work on behalf of Argentina’s poor? And a related question: At what point did she begin to guess and when did she know for certain that she was mortally ill?

What the biographies agree on and what they offer that is entirely missing from the film is a vivid sense of Evita’s uncanny physical presence.5 People reacted physically to this woman who spoke of blood rushing to her hands and head, and they remembered the experience long afterward. Friends from her acting days were struck by her exceptionally tiny breasts, buck teeth, and pale, translucent skin that was always clammy and cold to the touch. Perón recalled that at their first meeting, “her hands were reddened with tension, her fingers knit tightly together, she was a mass of nerves.” Even after she bleached her hair and her beauty became saintly, ethereal, her appearance continued to unsettle. In retrospect, people wondered if the cancer that caused her death at thirty-three made her cheekbones more elegant and gave her a luminosity she had lacked before. Many men came to see her as incomparably beautiful-with the strange qualification that she had less sex appeal than any other woman on earth.

At least some of Evita’s magnetism during her lifetime drew on this morbid physicality-a powerful aura that grew to horrific proportions after her death. Evita’s last wish was that no man should touch her body, but hours after she died she was turned over to an embalmer, a vain obsessive who had become famous in mortuary circles by arranging the hands of the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla to look as if they were alive and playing “El Amor Brujo.” Every day, all day, this man devoted himself to Evita, faithfully draining blood from her heels, pumping bile out of her abdomen, filling her with glycerine and formaldehyde, and coating her with scented oils. He worked for a year, until he was satisfied that she was “incorruptible.”

This story and the weirder story of what followed are told in Santa Evita, an extremely entertaining if depressing novel by Tomás Eloy Martínez. The novel is based on fact. It’s an ingenious distillation of and meditation on years of interviews and detective work by the author (he puts himself into the story as narrator). And ithas the unstoppable momentum of someone pouring out an upsetting secret. The weirder story that it tells begins three years after Evita’s death, when plans were laid to overthrow Perón, and the new junta, knowing the symbolic power of Evita’s body, assigned a colonel to make sure it never again came to light. This colonel, a spy, a lecturer on secrecy and rumor, and an admirer of Kant and Edmund Burke, ended up hijacking the mummy and hatched a plan to keep it moving and out of sight.

And here it begins to dawn on us that we are, in fact, dealing with a foreign country, that although we Americans have our serial killers and church-burnings, we don’t yet indulge in this particular pathology. Evita’s corpse is deposited behind the screen of a movie theater that plays Abbott and Costello movies; the daughter of the theater owner becomes attached to her and calls her “Sweetie.” After this, the body is moved around. It seems to have certain powers: as if by whim it might emit noxious odors, or have an inviting smell, like fresh flowers or herbs; sometimes it glows in the dark. And it ruins lives. One army officer who stores Evita in his attic falls in love with her, and when his pregnant wife climbs upstairs to see what is going on he panics and shoots her. The mastermind colonel ends up a destitute drunk, convinced that Evita has been stolen from him and buried on the moon.

Eloy Martínez is a movie buff, and the novel has a cinematic feel: the narrator, moved equally by pity and disgust, serves pretty much the same function as Joseph Cotten trying to decipher the mystery of Citizen Kane. But the novel leaves us without a rosebud. “Little by little Evita began to turn into a story that, before it ended, kindled another. She ceased to be what she said and what she did to become what people say she said and what people say she did.” The heroine must remain a mystery. The real subject is her afterlife in public memory.

So we’re back, again, to the mystery of fame. This is the place where the Argentine fixation on Evita and the American interest in her intersect. Of course the two interests are different:the first is urgent and based on visceral, often violent memories, the second casual, curious but detached.

The movie will satisfy neither. Still there is something almost moving in its enormous, misplaced gamble that the subject and scale of this project are enough, and that all the striving has been worth it. This poignance is best captured in the new Webber-Rice song, “You Must Love Me,” that has been added near the end, by which point the audience is exhausted from the unvaried flow that has gone before. Madonna/Evita, lying sick and depleted in a hospital bed and singing in the soft, fluttery voice she adopts for emotive passages, asks unanswerable questions (Where do we go from here? Why are you by my side?) and repeats the song’s title over and over:a command, then finally a desperate request for reassurance. She wants her husband to love her. But as happens so often in this movie we sense that it’s our love that she’s asking for. What a pity she’s failed to win it.

This Issue

February 20, 1997

-

1

This coincidence, like the early attraction to death poems, is one of many places where the pathetic youth seems to foreshadow the famous fate; another is the coincidence that the girl’s father and brother were named Juan, like her future husband, and her mother was Juana. ↩

-

2

Even so, there have been protests in Argentina over the production’s Englishness. The score and lyrics are by two Englishmen who have colonized an international grab bag of subjects, from Victor Hugo to Vietnam to the Gospels. Alan Parker is also English (though his first movie, Bugsy Malone, a musical homage to 1930s gangster flicks that starred children as the thugs and the molls, shows a man obsessed, perhaps unhealthily, with American culture). And then there’s Jonathan Pryce, who plays Juan Perón; his Englishness is particularly awkward when you consider Argentina’s recent trouncing in the Falklands, and the fact that Perón’s most loathed enemy, the aristocracy, was a hotbed of Anglophilia. (Jonathan Pryce presents Americans with a different but related problem: Perón rose to power on his appeal to the poor, but Pryce is best known here as the spokesman for Infiniti, the luxury car. In the latest commercial he stands outside a masked ball-a decadent, grotesque display of wealth-and invitingly cocks an eyebrow.) ↩

-

3

According to Jon Lee Anderson, who will publish a biography of Che Guevara this spring, Che and Evita never met. At best their interaction was one-way, consisting of a letter Che wrote to Evita in care of her foundation-a letter which would have been one out of many thousands-requesting money for a jeep in which to drive around South America. There is no known reply. ↩

-

4

Alan Parker is also the director of Fame, a kind of Stage Door set in a performing-arts school. ↩

-

5

There’s also no sign of Juan Perón’s constant rash from psoriasis, which required daily medicinal concealer and may suggest some stress-related misdirection of energy. ↩