In response to:

The Real Thing from the January 9, 1997 issue

To the Editors:

In her article titled “The Real Thing” [NYR, January 9], Janet Malcolm wonders why it matters whether E.J. Bellocq was an asexual dwarf or a man of ordinary proportions and propensities. Surely she sees that John Szarkowski’s understanding of the Storyville photographs requires a Bellocq who was a freak. For Szarkowski, Bellocq’s deformities led him to empathize with the prostitutes, who were also outcasts. His small size and sexual passivity allowed them to open up to his camera in a way that would have been impossible with a potential customer. Bellocq’s pictures are “the real thing” precisely because Bellocq himself was not a real man.

When he mounted his Bellocq show in 1970, Szarkowski also had to deal with the problem that the photos were potentially offensive. By asserting that Bellocq’s interest in his subjects was not sexual, Szarkowski placed the photos within the tradition of the nude, out of the category of photographic pornography. Szarkowski’s evidence for a dwarf Bellocq was slim, but it was essential to his presentation.

But Szarkowski’s version does not explain the pictures. If they were intended as art, then why are they so different in style, composition, and feeling from the studio photography of the period? And, if what Bellocq and the prostitutes shared was their status as outcasts, then why do the women appear to be so happy?

On the other hand, if we accept the new evidence that Bellocq was physically ordinary, a simpler explanation presents itself. As Malcolm sees, the women pose for Bellocq with beautifully unguarded smiles, as if “sharing an extremely pleasant moment” with him. They are having fun being photographed. Malcolm quotes Susan Sontag’s observation that the pictures are “goodnatured and respectful.” Yet they are also sexually highly charged. The best explanation is that the subjects are Bellocq’s lovers, and the photos are a personal record of mutually enjoyable sexual relationships.

Once we posit that the pictures were not intended for exhibition or sale, the problem of Bellocq’s modern-seeming taste is also resolved. If Bellocq did not pose his subjects in the self-consciously “artistic” settings of his time, the simplest explanation—as Malcolm acknowledges—is that he was not trying to make art.

The new edition of Bellocq photos includes a number of previously unpublished prints in which the faces have been scratched out. In rhetorically heightened yet ambiguous language, Malcolm appears to propose a literal “defacer” (probably Bellocq himself) intent on metaphorically obliterating the humanity of his subjects. She ignores the obvious reason for scratching out a face in a sexually explicit photo: to disguise the identity of the subject. Some of these women may have emerged from the brothels to lead conventionally respectable lives.

When Malcolm describes the “savage black scrawls” that “cover” the faces in the modern prints made from these ruined negatives, she assumes that Bellocq printed them. She invokes the “violation and violence” of the contrast between the white linen bedclothes and the “indelible blackness of the blotch,” causing the viewer to recoil as if “before a scene of rape.” The defacer, says Malcolm, has “inscribed a chilling metaphor for the brutality of the enterprise that offers bodies for sale.” At long last, she concludes, we have arrived at “the real thing.”

But of course we have not. Bellocq made no black blotches covering women’s faces. He scraped away the emulsion of the reversed images on the plate negatives, leaving clear glass. A negative is not an intelligible image of anything at all, and does not become one until it is printed. Yet there is no evidence that Bellocq printed these plates, and it is unlikely that he did so. It is far too anachronistic to assume that he could have conceived of prints made from these ruined negatives as works of art in the modern fashion, or as having any value or meaning at all.

In 1970, John Szarkowski, although he could mount photos of prostitutes on the walls of the Museum of Modern Art, could not admit the possibility that they had enjoyed consensual sex with their photographer. Instead, he gave us Bellocq the dwarf—a tragic artist, powerless and outcast. In 1996, Janet Malcolm seems equally ill at ease with the comfortable sexual relationships that emerge from the photos, and so she conjures up Bellocq the defacer—an enraged male proclaiming his dominance over his powerless female subjects. This shift over the last quarter-century tells us something about the changing art-world clichés of our era. It tells us nothing about the reality of Bellocq’s own place and time, as we can see it in his engaging photographs.

Joseph L. Ruby

Silver Spring, Maryland

Janet Malcolm replies:

Joseph L. Ruby raises—or re-raises—an interesting question: Can you tell from a photograph whether the subject and the photographer have slept together? Georgia O’Keeffe, in her introduction to the 1978 collection of photographs of her (a number of them nude) by Alfred Stieglitz, writes: “When his photographs of me were first shown, it was in a room at the Anderson Galleries. Several men—after looking around awhile—asked Stieglitz if he would photograph their wives or girlfriends the way he photographed me. He was very amused and laughed about it. If they had known what a close relationship he would have needed to have to photograph their wives or girlfriends the way he photographed me—I think they wouldn’t have been interested.” We know from Edward Weston’s journals that some of his most famous nude photographs—of Tina Modotti, Sonya Noskowiak, and Charis Wilson, among others—were done as a kind of pre-coital exercise.

If these photographs tell us anything, it is that Bellocq probably did not sleep with his subjects. Whether he was a dwarf or of normal height has nothing to do with it. There are many photographers of normal height who do not sleep with their models. It is no disgrace to not sleep with your model. But as the Stieglitz and Weston photographs (and other photographs in this genre) confirm, a lover’s lot is not a happy one—O’Keeffe, Modotti, Noskowiak, and Wilson look very grave, almost grim—and the Storyville prostitutes’ look of cheerful insouciance practically spells out the uncomplicated platonic nature of their relationship to the photographer. The Bellocq pictures have a kind of holiday spirit—the sex workers on their day off. They are horsing around with a pal who has a camera.

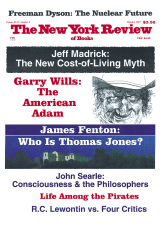

Ruby’s theory that the faces were scratched out on the plates to hide the identity of the models makes a lot of sense. I agree that it is the most obvious explanation. However, it leaves unanswered the question of why, in a number of cases, a woman is de-faced in one plate and left whole in another. In one picture (reproduced on the cover of The New York Review of January 9) a woman in a body-stocking is looking coolly out at the viewer, but in another, the same woman’s face has been scratched out.

In the final three paragraphs of his letter, Ruby leaves off speculating about matters that cannot be settled one way or the other—matters where his guess is as good as mine—and moves on to interpreting my text, as if it, too, was unknowable and therefore fair game for fantasy. To correct his bizarre misunderstanding of my essay would require the effort of writing a new one. I will let the old one speak for itself, reiterating only that of course the scratches were made on the plates and not on the prints, and of course the social and aesthetic statements made by the defaced photographs (a species of found object) are creations of the present.

This Issue

March 6, 1997