To the Editors:

It is excellent to read about the fascinating and undeservedly neglected work of Albert Eckhout in Benjamin Moser’s perceptive essay [“Dutch Treat,” NYR, August 12], but I’d like to modify his optimistic statement (citing Hugh Honour) that Eckhout’s eight life-size portraits are “the first convincing European representations of American Indian physiognomy and physique.” Setting aside John White’s work in Virginia in the 1580s, the Eckhouts do indeed offer a pioneering and remarkable record from observation of artifacts and produce, as well as flora and fauna. But on internal evidence, they are probably not painted in situ. If you look carefully at the face of the Tapuya woman or of her Tupi counterpart, and likewise at their male companions, their faces and features become rather familiar: soft, rounded, even a little doughy, with an undefined nose, this kind of physiognomy looks out from any number of Dutch portraits of the same period.

Eckhout has arranged a splendid accumulation of evidence around the figures as if on a botanical plate (the banana plant, for example, is shown at every stage of its cultivation), and he has dressed and equipped his subjects in items from a princely cabinet of curiosities. It is likely, from these indications, that Eckhout brought back drawings, sketches, and objects, assembled the compositions in his studio to make the paintings, and then fell back on local models, coloring the pairs of emblematic inhabitants in graded shades of light- to reddish-brown (much damaged, with the primer showing through, when I was in Copenhagen to see the pictures). Happily, the couple of African-born figures are exceptions, for Eckhout does not seem to have substituted their faces or bodies. These two paintings are, like the portrait of Don Miguel de Castro attributed to him, much the most powerful and convincing of the eight full-scale portraits in the set.

I am not making fun of Eckhout or trying to diminish the value of his paintings. But they lie somewhere aslant the notion of historical evidence. The method of compiling an image can alert us to the fantastical, or at least mythic, aspects he brought to the interpretation of Brazilians. Benjamin Moser mentions “the exhibition’s most outrageous crowd-pleaser”—the Tapuya woman holding a severed arm in one hand while a severed leg pokes out of the beautifully painted basket on her back, looking out at the viewer as boldly as a burgher’s wife from her casement window. Between her legs, a dog with sharp teeth is lapping water, while just above his jaws, very near her ornamented pubis, a war party is streaming past, with Indians shown in full cry after some victim. These scenes are extremely unlikely to be the result of plein air picture-making, or any kind of direct observation.

Cannibalism in the Americas is a vexed historical question, but, without taking sides on the veracity of the accounts, it is worth pointing out that the chroniclers’ accounts are secondhand, repetitious of one another, and they delight in projecting images of savages barbecuing humans and other atrocities.

Eckhout’s evidence need not be discounted—of course not. But it is not transparent. With his unique material and flamboyant compositions, he is a most precious witness to aspects of the culture of the Americas, as reported by some of the earliest travelers. Ramon Pané, for example, was left behind by Columbus on the island of Hispaniola to gather information about the local inhabitants and, having been picked up and brought back to Spain in 1498, gave a detailed and extremely influential account of their ways, including methods of inducing trance through inhaling a plant called cohoba through their noses. In the tremendous Tapuya dance by Eckhout reproduced in your pages, the two women to the side are not hiding their merriment behind their hands, but probably joining in the general intoxication of the event.

Marina Warner

London, England

Benjamin Moser replies:

The excellent catalog of the recent Albert Eckhout exhibition agrees with Marina Warner’s suggestion that the paintings were not actually executed in Brazil, as was long believed, but in the Netherlands.

But it does not follow from there that Eckhout must have used local (Dutch) models. There are certainly similarities of pose with other Dutch paintings from the period—hardly surprising—but the Dutch physiognomy Ms. Warner thinks she discerns is in the eye of the beholder—not, I should add, of this beholder. A great number of Eckhout’s sketches survived, undoubtedly made from life, and in Brazil; in them, many of the characters in the finished paintings appear.

I never stated that the paintings are “the result of plein air picture-making.” Golden Age Holland was not Barbizon; I cannot think of a single seventeenth-century Dutch painting made en plein air. I do not understand Ms. Warner’s conclusion that because Eckhout’s works are not literal snapshots, they cannot be the result of “any kind of direct observation.” That is like saying that because Vermeer’s View of Delft is not an accurate topographical representation of that city, it cannot be the result of “any kind of direct observation.”

Ms. Warner also writes, with respect to the cannibalism of the Tapuyas, that “the chroniclers’ accounts are secondhand, repetitious of one another, and they delight in projecting images of savages barbecuing humans and other atrocities.” I assume she is here referring to the authors of written chronicles, not visual ones like Eckhout’s. If that is the case, I must rally to the defense of the marvelous chroniclers of Netherlands Brazil, especially the two most eminent, Manoel Calado and Caspar van Baerle, neither of whose accounts is secondhand or repetitious. Dutch Brazil is extremely well documented, and I know of no grounds to believe that the Tapuyas were not cannibals.

As for what the two Tapuya women are doing off to the side, Ms. Warner’s guess is as good as mine.

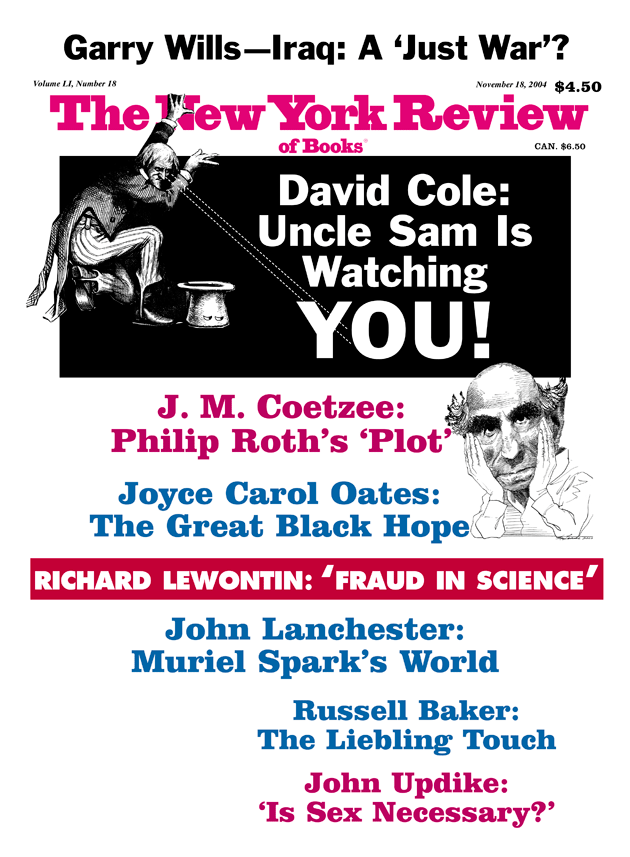

This Issue

November 18, 2004