1.

A common factor in conventional war movies, whether they are made by Americans, Europeans, or Asians, is the lack of visible enemies. They are there, in the way Indians were there in old westerns, as fodder for the guns on our side, screaming Banzai! or Achtung! or Come on! before falling to the ground in heaps. What is missing, with rare exceptions, is any sense of individual difference, of character, of humanity in the enemy. And even the exceptions tend to fall into familiar types: the bumbling or sinister German, hissing about ways to make you talk, the loud, crass American, the snarling Japanese.

Colonel Saito, the camp commander in The Bridge on the River Kwai(1957), played by Sessue Hayakawa, shows some personal qualities, but they still fall within the well-trodden domain of the stoic samurai, growling his way to the inevitable ritual suicide. Then there are the epic battle films, such as Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), about the attack on Pearl Harbor, jointly directed by an American (Richard Fleischer) and two Japanese (Kinji Fukasaku and Toshio Masuda). We see historic figures barking orders on the bridges of aircraft carriers and the odd Japanese pilot baring his teeth as he approaches the USS Arizona, but there is no time in the midst of all the gunfire for intimacy.

There are reasons for this lack of enemy characters, both practical and propagandistic. It was hard in Hollywood, until recently, to find enough competent actors to play Japanese roles (or Vietnamese for that matter). Japanese soldiers were usually played by an assortment of Asian-Americans who shouted a few words in barely comprehensible Japanese. Hollywood could have done better but too few people cared. If finding convincing foreign actors was not easy in California, it was even harder in Japan. American soldiers in wartime Japanese propaganda films were often played by White Russians who hardly spoke English. Sometimes Japanese actors with wax noses and blond wigs had to do. And the stock GI in postwar Japanese movies, raping local girls and stomping across the tatami floors in his boots, is usually played by any available white male in need of some easy money. The same principle holds for Chinese movies, by the way, where most “Japanese devils” speak in heavy Chinese accents, and Americans in every accent known to Caucasian man.

The propagandistic reason is perhaps more important than the practical one. Most war movies have been about heroes, our heroes, and individual differences among the enemies were irrelevant, since their villainy could be taken for granted. In fact, showing individual character, or indeed any recognizable human qualities, would be a hindrance, since it would inject the murderousness of our heroes with a moral ambiguity that we would not wish to see. The whole point of feel-good propaganda is that the enemy has no personality; he is monolithic and thus inhuman.

Like the classic western, the war movie as patriotic myth has been challenged more and more since the heroic days of John Wayne and Robert Mitchum. Think of Catch-22 or Platoon or Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. And even before World War II, such films as All Quiet on the Western Front and La Grande Illusion treated the enemy as human beings. But Clint Eastwood is the first director, to my knowledge, who has made two films of the same battle, showing both sides from the perspective of individual soldiers with fully developed characters. Deftly, without polemics or heavy-handed messages, he has broken all the rules of the traditional patriotic war movie genre and created two superb films, one in English, the other in Japanese: Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima. The latter, in my view, is a masterpiece.

The choice of Iwo Jima, where the first US landing on Japanese soil took place in February 1945, makes perfect sense. Almost 7,000 Americans and 22,000 Japanese died in thirty-six days of fighting on that small volcanic island 650 miles from Tokyo. The famous photograph by Joe Rosenthal of six GIs hoisting the US flag on top of Mount Suribachi made the battle into an instant myth, heralding victory over Japan, just as enthusiasm and money for the war was running out in the US. This image, reproduced in every newspaper, on postage stamps, in sculptures, trinkets, posters, magazines, banners, monuments, and not long after the war in a movie starring John Wayne, was sold to the public as the epitome of American heroism and triumph. To raise morale and sell war bonds, three of the original six flag-raisers who survived, John “Doc” Bradley, Rene Gagnon, and Ira Hayes, were paraded around America like movie stars, mounting a papier-mâché Suribachi in a Chicago baseball stadium, being feted in Times Square, dining with senators and congressmen, meeting the President and finally, after the fighting was over, John Wayne himself.1

Advertisement

The gap between the real horror of Iwo Jima and the razzmatazz back home proved to be too much for Ira Hayes, a Pima Indian, who took to drink, and whose wretched life, beginning on an impoverished reservation and ending face down in a freezing ditch in Arizona, had its own mythical qualities, lamented in a ballad sung by Bob Dylan. Gagnon, too, although a willing huckster to begin with, died young as an alcoholic. And Bradley, whose story, written up in a best-selling book by his son James, holds Flags of Our Fathers together, had nightmares for the rest of his life.

But there is another reason, apart from patriotic mythology, why Iwo Jima was a good choice, for there, trapped in the black volcanic sand, the Americans really did fight a faceless enemy. Led by Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the Japanese had dug themselves into a vast warren of caves, tunnels, and pillboxes. Unsupported by any sea or air power, they were under orders to fight to the death, hoping against hope that this would deter an invasion of Japan. Lethal but invisible, they spent days and nights in sauna-like conditions, with food and water supplies running out fast, killing as many enemies as they could before, in many cases, blowing themselves up. No wonder the Marines thought of their enemies as rats who had to be burned out of their holes with flamethrowers. Many Americans on Iwo Jima had the words “Rodent Exterminator” stenciled on their helmets.2

You realize that Eastwood has made a highly unusual war movie right from the beginning of Flags of Our Fathers, when the US Navy steams toward Iwo Jima in full force. Not yet realizing quite what’s in store for them, the young soldiers still have time to cheer the US bombers streaking overhead, as though they are at a football game—just as the audience is invited to do in more conventional pictures. One man, in his excitement, falls overboard. The good-natured laughter of his buddies suddenly freezes when they realize that no ship is going to stop for one individual Marine thrashing about in the ocean. The war machine rolls on. “So much for leaving no man behind,” mutters “Doc” (Ryan Phillippe) under his breath.

Much is made in the film of the fact that these soldiers did not think of themselves as heroes. They were ordinary young men sent into a hellish place, from which all bright color has been drained in the film, as though the sulfurous landscape itself is dead. All you could do, in the words of Ira Hayes, was to “try and stop getting shot.” Although the story is centered around “Doc,” the most interesting character in the film is Ira, beautifully acted by Adam Beach, who grew up on an Indian reservation himself. Of the three, Hayes was the most dedicated soldier. Military service offered an escape from poverty and degradation. The US Marine Corps was the first and only American institution where he felt accepted. Nicknamed Chief Falling Cloud, he was popular with his fellow soldiers, and he repaid them with his loyalty.

This is shown in the movie in various ways. Hayes never wanted to leave his unit to join the promotional hoopla in the US. He is the one who cracks up at an official function when he meets the mother of Sergeant Strank (Barry Pepper), one of the flag-raisers who was killed soon afterward. “Mike, Mike,” he sobs, “he was a hero. Best Marine I ever met.” That Hayes survived, only to be paraded around football stadiums and reception halls in order to sell war bonds, fills him with shame.

There are moments in the film when the phoniness triggers horrifying visions for the survivors. Firecrackers and roaring crowds sound like mortars and gunfire, and memories come flooding back of buddies left behind screaming. At an official banquet, where “the heroes” are served a dessert in the shape of Mount Suribachi with the flag raised on top, the hovering waiter whispers “chocolate or strawberry?” before covering the sugary scene with blood-red sauce. That some bars still refuse to serve Hayes, as an Indian, adds to his sense of displacement and humiliation. Drunk and brawling, he is called a “disgrace to his uniform” by one of the military promoters, and finally he gets sent back to the battle front, the only place he felt respected, and in some way, perhaps, at home.

Despite his sympathetic depiction of Hayes, Eastwood has been accused of racism for not including black soldiers in Flags of Our Fathers.3 There were, in fact, more than nine hundred African-Americans among the 110,000 men on Iwo Jima. If Eastwood had followed the conventions of postwar war pictures, he might have included at least one by dividing the heroes among various ethnic types: the doughty WASP, the slow-talking southerner, the wise guy from Brooklyn, the tough black from Chicago. But Eastwood is not dealing in types. He shows how a few men, who actually existed, tried to cope with a terrible experience.

Advertisement

The problem with any film trying to make us feel the horror of war is that it is an impossible enterprise. Watching combat on a screen, no matter how skillful the camerawork, acting, soundtrack, or digital simulation, can never make us feel what it was really like on Iwo Jima. The harder a film tries to reconstruct reality, the more one is aware of the futility. Steven Spielberg, Eastwood’s co-producer, was a technical wizard in Saving Private Ryan and Schindler’s List, but, mercifully, the real experience of Normandy and especially Auschwitz still remains wholly beyond our grasp. But Eastwood does manage to provide a hint (and a hint is all that is feasible) of the way war affects an ordinary soldier: the terror, the cruelty, but also the moments of selflessness, even grace.

Eastwood gives us glimpses of some of the cruelty: the casual murder of two Japanese POWs by GIs who are too bored to guard them; the tearing apart of an American soldier dragged into a cave by a group of half-crazed Japanese; the remains of Japanese soldiers splattered on the rocks after they detonate hand grenades against their own bodies. But although Eastwood is very good at showing the gap between the sickening reality of war and the stories we make up afterward, he does not deny the possibility of heroic acts. We see how “Doc” Bradley risks his life in lethal crossfire by crawling out of his hole to help a wounded soldier. It is an act that has nothing to do with patriotism, “fighting for freedom,” or anything of the kind, and everything to do with simple decency, which is rare enough to be called heroic.

Bradley evidently never talked to his children about his wartime experiences, and when the press called him on anniversaries, he told his son to say he was away on a fishing trip. But in the film, near the end of his life, gasping for breath in a hospital bed, he tells his son of one memory of Iwo Jima. It is the last, haunting image of the movie. Men like Bradley, in his son’s words, “fought for their country, but died for their friends,” and we “should remember them the way they were, the way my dad remembered them.” We then see “Doc” and his friends strip to their underpants and run into the sea, splashing about and yelling in youthful exuberance at the sheer pleasure of still being alive, at least for a few more hours, or perhaps days. In that simple scene, where not a shot is being fired, you feel something of the horror of the wanton destruction of human beings whose adult lives had barely begun.

2.

Empathy is harder to muster for enemy soldiers, especially soldiers from strange countries, whose languages we don’t speak. One might be appalled by the mass murder of Japanese in Hiroshima or Nagasaki, just as one deplores the deaths of Bangladeshis in a terrible flood, or villagers in Darfur. But as long as they have no recognizable faces, their suffering remains almost abstract, a question of numbers. To make a convincing film about people in an unfamiliar culture is very difficult. European directors in the US often have a hard time catching the spirit of the place. For a foreign director to make a Japanese film without any false notes or cultural slip-ups, a film in which the characters, who speak in subtitled Japanese, are wholly convincing and thoroughly alive, is an extraordinary feat. Several filmmakers, from the pre-war Nazi propagandist Arnold Fanck to the great Josef von Sternberg, have tried. To my mind, Clint Eastwood is the first to have pulled it off.

Letters from Iwo Jima opens and closes with scenes of Japanese researchers digging in the caves for anything left behind by the soldiers who died there. They find a sack full of unposted letters from soldiers to their families. The narrative of the movie is based on some of these letters, as well as the remarkable letters written and illustrated by General Kuribayashi, published several years ago in Japan.4 Some of the letters to his family were actually written in the 1920s and 1930s, when he lived and traveled in North America as a military attaché. They are used as a device to flash back to an earlier, more peaceful life of a humane aristocrat who liked and understood America well enough to realize the folly of going to war against it. Perhaps for this reason, he was sidelined for much of the war by more militant officers, and given the thankless task at the end of fighting a suicidal battle.

Ken Watanabe plays the part of Kuribayashi with just the right degree of noblesse oblige toward his men and contempt for the less imaginative and sometimes brutal officers who regard him as a soft America-lover. It was Kuribayashi’s idea, carried out against a great deal of obstruction, that the Japanese should dig themselves in rather than stage futile banzai charges on the beaches. Although he was quite aware of the ultimate fate of his army, he saw no merit in wanton self-destruction. Unusually for a senior Japanese officer in World War II, the general intervenes when he sees a sergeant abusing men in his platoon. Common soldiers were used to being treated brutally. But there is nothing sentimental about the portrayal of Kuribayashi. He is not a closet pacifist but a professional Japanese soldier, who wrote to his wife:

I may not return alive from this assignment, but let me assure you that I shall fight to the best of my ability, so that no disgrace will be brought upon our family. I will fight as a son of Kuribayashi, the Samurai, and will behave in such a manner as to deserve the name of Kuribayashi. May ancestors guide me.5

The only other character in the story with any personal knowledge of the enemy is Baron Takeichi Nishi (Tsuyoshi Ihara), a dashing equestrian who won an Olympic medal in Los Angeles in 1932 and entertained Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks at his house in Tokyo. Instead of hacking a wounded GI to pieces, as some of his men might have done, he reminisces in English about the good old days, telling the dying American of his Hollywood connections. “No kidding,” says the GI, shortly before he expires. Nishi has the hearty manners of a sporting Englishman. He is rather like the Erich von Stroheim character in Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion, a member of the international aristocracy, at home in any place where wine, horses, and women have an acceptable pedigree.

The ordinary Japanese soldier, trained to jump up at the mere mention of the emperor, to think of foreigners as devils, and to exalt violent death as the highest honor, is harder for a modern audience to comprehend. He seems faceless, because Japanese military policy was to stamp out all signs of individual character, more than was the case with US Marines. Even under normal conditions the tendency in Japan is to “knock in the nail that sticks out.” During the war this tendency became extreme. Any sign of unusual behavior was liable to be punished by the thuggish Kempeitai (military police) or Tokkotai (special higher police). In one of the few scenes in Letters from Iwo Jima that takes place in Japan, we see a Kempeitai officer ordering a young recruit to shoot someone’s pet dog, as a test of his toughness. When the recruit tries to spare the dog, he is dismissed and sent to die on Iwo Jima.

This recruit, named Shimizu (Ryo Kase), is one of the soldiers in Eastwood’s film whose mask of blind obedience and suicidal fanaticism fails to hide a more reflective, even compassionate nature. When another young soldier, Saigo (Kazunari Ninomiya), refuses to kill himself with a hand grenade after the others in his platoon have all committed suicide, Shimizu threatens to shoot him for his treachery. But in fact he, too, feels that he is too young to blow his brains out in a doomed war, and they decide to save their own lives by surrendering to the Americans. Shimizu goes first, but is killed by his American guard. Saigo fails to move, which saves him.

The hesitant voicing of growing doubts, the dangerous signs of humanity, are expressed in dialogues between the young soldiers that could easily have slipped into mawkishness, but in fact are intensely moving. Kuribayashi, the compassionate general, may have doubted the wisdom of going to war, but he remains a professional soldier; war is his business; he never doubts his duty to carry on until death. Saigo, acted by a teenage pop idol, is a baker in civilian life, with a pregnant wife waiting at home. He was dragged into the conflict without wanting to be part of it. When the neighborhood committee comes around to his house with his draft card, congratulating him on the honor of being ordered to die for his country, Saigo cannot disguise his anguish. Ninomiya, the teen star, is absolutely convincing in this part, for you realize how very young many of these men were, and how ill-suited to be turned into killing machines.

Saigo, indeed, is very different from Ira Hayes, who found a home and a purpose in the Marines. Like Shimizu, the aspiring Kempeitai who couldn’t bring himself to kill a child’s pet dog, Saigo is out of place, used as fodder in a war that doesn’t make sense to him. Others around him have internalized the fanaticism of the Japanese militarized state. Lieutenant Ito, for example, played with a little too much histrionic effect by the young Kabuki actor Shido Nakamura, is obsessed with driving his men to suicide. Others, like soldiers everywhere, use war as an opportunity for licensed sadism. Saigo and Shimizu are interesting, because they continue to think for themselves, despite every attempt to stop them from doing so. Unlike Baron Nishi or Kuribayashi, they have no knowledge of the world outside Japan. But their personal integrity remains intact in what is otherwise a depiction of Hell.

In the real Battle of Iwo Jima, of the 22,000 Japanese left to defend the island only about one thousand survived. Some surrendered, others were caught before they could kill -themselves. In the movie, Saigo is the only one of his unit to live on. We don’t know how the real General Kuribayashi died. There are stories that he died a samurai’s death by his sword. Possibly he was torched or blown up in his cave. In Eastwood’s film, he leads a suicidal charge into the American camp, which almost certainly did not happen. Saigo is with him, but is knocked down by the Marines who capture him. In the final shot of Letters from Iwo Jima, we see him on the ground in a long line of wounded American soldiers, his face turned toward the camera. Lying under his army blanket, waiting to be taken off the island of death, Saigo is no different from the Americans lined up beside him, and yet it is unmistakably him; and that is the point of Eastwood’s remarkable movie.

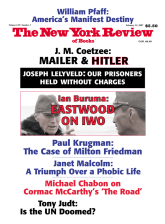

This Issue

February 15, 2007

-

1

Bradley, Gagnon, and Hayes actually played themselves, alongside John Wayne, in the 1949 movie Sands of Iwo Jima. ↩

-

2

John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (Pantheon, 1986), p. 92. ↩

-

3

See, for example, Earl Ofari Hutchinson in The Huffington Post, October 24, 2006. ↩

-

4

“Gyokusai Soshireikan” no Etegami(Tokyo: Shogakukan, 2002). ↩

-

5

Quoted in Thomas J. Morgan, “Former Marines Remember the Most Dangerous Spot on the Planet,” The Providence Journal, June 28, 1999. ↩