1.

You would think first of all of a village fair: the entire community of Germantown, Northwest Philly, taking itself up on the brightest of bright sunny fall days and moving en masse, clumps of people—groups of young men in the obligatory hoodies and low-riding jeans, moms pushing strollers, dads lugging car seats, and everywhere children, from toddlers on up, being pulled along (“You’ll remember this all your life!”)—almost all of them African-American and all melding together, as they crowded toward the entrance to Vernon Park, into a full running, laughing stream. Hawkers hawked “Obamaniana”—the man’s face glowing on posters, some huge, floating above the crowd; his name carved in wood or stone; the Obama keychains and wallets and everywhere the volunteers with their blue buttons and their clipboards, making sure it all works smoothly.

Once in the park, enfolded in those several thousand happy people, there was the dancing. Over the loudspeakers, inevitably, “The Power of One!” and of course “Power to the People,” and beneath where I stood on the riser, among the generally bored press corps, two blond girls danced and laughed and bumped hips. I chat with a local volunteer, a middle-aged lady with a café au lait face, and when I ask her how it’s going she fixes me first of all with a slightly scolding look—how can you ask that?—and then says it simply and without doubt, “Oh, we’re gonna do it this time. This time it’s ours!”

Knowing politicians and his schedule of four appearances on this one bright day in Philly I’d been prepared to wait but it was only twenty minutes after the appointed time when after a series of very quick introductions from the young black mayor, Michael Nutter, and Senator Robert Casey, and the gravel-voiced bearish Governor Ed Rendell—hardly more than a minute each, a never-before-glimpsed discipline from politicians—he rose from a stairway at the back of the stage into an explosion of sound, grinning with pleasure in an open-collared white dress shirt and black dress slacks.

He seems slender and slight and young, astonishingly young, and you notice first of all, for it is impossible not to, the physical grace; he moves like an athlete much more than a politician, taking pleasure in his body: bursting up onto the stage, the lanky highly stylized movement, shoulders bent slightly concave, gathering everything into those constantly clapping hands, using the hands in their clapping to acknowledge the crowd, his head nodding all the while, as if he is drawing his energy only from them and showing that energy with his clapping and nodding, with the bursting energy of his body that is an embodiment of theirs, an embodied picture of what they’re giving him. He prances with evident pleasure around the little stage, moving his head in big theatrical nods, embracing each politician in turn, big full-bodied embraces, and again one thinks of an athlete on the sidelines or in the dugout: all of it is done with the unhindered pleasure of the body, all of it says confidence and pleasure, as if this, being bathed in the huge cheers, taking sustenance and energy from the wave of sounds and the shouts of his name, is the place where he breathes his true oxygen, where he really lives. He seems made to be precisely here—in the midst of these thousands of sun-drenched cheering people. On this perfect mid-October day, there is only him and them and what is between them.

“How’s it goin’, Northwest?” That salutation, and the enormous opening roar in response, tells you that he knows these people and they know him. “What a beautiful day the Lord has made!” It’s a black crowd and his speech immediately acquires, not broadly but noticeably, a tinge of blackness: the Southern tones, the slight mid-Carolina or mid-South softening, the falling final g’s. He knows these people, each one of them, that’s what the grin says—wherever he comes from he will be this day the local boy made good: theirs. They can take pleasure in that and he can, too, and he is telling them he knows it.

He goes quickly through the thanks to the local politicians and then moves into the stump speech, a stripped-down version for this heavily packed day, and I was impressed again by the absolute clarity and simplicity of the language. The transformational “post-partisanship” of the primaries is nowhere to be seen, burned away in the fires and fears of the financial crisis. Frank, rousing Democratic populism now: jobs and the hurt people are feeling. “Now’s not the time for fear,” he declares. “Now’s the time for leadership. The disastrous policies of the last four years cannot continue. We have seen the final verdict of Bush economics. We don’t need four more years of that.”

Advertisement

The ease and simplicity of the message: things are bad now, real bad. Do you want that to continue or do you want things to get better? In this construction McCain is Bush. The two are identical and that identification, which handcuffs the Republican to the disaster wrought by the incumbent in the White House, and which is taken for granted here, is all you need to know.

In the midst of this he lets drop today’s “bite.” “I want to acknowledge,” he says, “that Senator McCain tried to tone down the rhetoric at his town hall meeting yesterday.” It is the line the traveling press, who know his stump speech by heart, have been waiting for. Looking across from my riser toward the reporters gathered at the long card tables arrayed on the grass, I see heads suddenly bend over laptops, fingers flying. The day before, in a town meeting in Lakeville, Minnesota, McCain had taken the microphone from an elderly woman who was saying she didn’t “trust Obama” because she had “read about him and he’s”—a big pause here—“an Arab.” McCain, who had been shaking his head, took the mike and said, “No ma’am, no ma’am, he’s a decent, family man, citizen, that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues, and that’s what this campaign is all about.” Earlier he had told another angry supporter, a man who had shouted that he would be “scared” to bring up his child in a country with a President Obama, that Obama was “a decent person, and a person that you do not have to be scared as president of the United States.”

Now Obama, in the midst of this increasingly raucous conversation with the crowd, has issued his answer and by the time I would return to my hotel room a few hours later there it would be leading that day’s news on all the cable networks. For the purposes of the “national campaign,” what the bloviators bloviate about, what the commentators comment about, what most Americans manage to glimpse of the campaign, this is what “really” happened that day: the campaigns continued to “dial back the rhetoric,” which in previous days “had grown increasingly poisonous.”

Indeed, the other bit of political news, which reinforced this now superseded “poisonous” plotline, had Congressman and civil rights hero John Lewis issuing a statement that seemed to compare the McCain campaign, in the increasing vehemence of its language, to George Wallace, whose overheated rhetoric had also led to an “atmosphere of hate,” and “because of this…, four little girls were killed on Sunday morning when a church was bombed in Birmingham, Alabama”—itself an overheated comparison Obama could now declare “inappropriate.”

Watching the day’s events, and their televised packaging, one is struck once again by the profound bifurcated strangeness of American politics. Impossible to know what is the “real” campaign. Was it that rousing event I was attending, full of uplifting words and calls to arms and inspiration, which so many children and young people will never forget? Or is it this battle of sound bites, carefully crafted each morning by the campaign “strategists” and tossed with casual precision by each candidate into the maw of the hungry press corps? Seen from Vernon Park the national campaign is a strange disembodied electronic cloud, floating out there in the ether, with an almost laughably tangential relation to what actually occurs before the people themselves. What would those who had attended the rally feel when they looked at their television sets that evening? Bewilderment? Disgust? Bemusement? Pity?

For the national campaign, on the other hand, for the commentators and bloviators and battalions of Democratic and Republican “strategists” ushered in and out of the television studios, the battle of the bites was the campaign, and that campaign had reached the point where “things were getting increasingly ugly.” There was no trace of this whatever at the event in Vernon Park, beyond that wisp of a sentence from the candidate acknowledging that his opponent had tried to “tone down the rhetoric…yesterday.” But he knew and every member of the campaign and press present knew—all the “professionals” knew—that this was all that had been said that day that would be part of the national campaign. And to all the commentators and strategists, and all the millions who that day would see and hear, on the cable stations and on talk radio and on the networks and the blogs only what they had produced, this was the real campaign, for which the rallies only existed as a kind of artificially constructed pageant. It was comprised of the cheering ranks of those who had already committed, out of which one could daily extract those tiny preformed packets of “news,” intended to persuade, via the electronic ether, those who had not.

Advertisement

Everything else they would never see. It existed only for the several thousand cheering people in Vernon Park on that bright morning in Germantown. They would never see, for instance, Obama’s riff on sweet potato pie. It came as he told a story about his campaigning “the other day in a little town in Ohio, with the governor there,” about how he and the governor suddenly felt hungry and “decided we’d stop right there and get some pie.” Now here began a little gem of a story, which had at its center the diner employees who wanted to take a picture with Obama, not least because, as they told him, their boss was a die-hard Republican and “they wanted to tweak him a little with that picture.” All this was heading toward a carefully choreographed finale, where the owner appeared personally with the pie for candidate and governor and Obama looked at the pie and looked at the pie-carrying die-hard Republican owner and “then I said to him”—perfectly elongated pause—“How’s business?”

This brought on great gales of laughter from the crowd. For the joke turned on a point already precisely made: How can even the most die-hard of die-hard Republicans, if he is thinking of his self-interest, how can he vote Republican this year? “If you beat your head against the wall,” Obama demanded of that faraway Republican with his pie, to a blizzard of “oh yeahs!” and “you got that right!” from the crowd, “and it hurts and hurts, how can you keep doing it?” But it was those two words, “How’s business?”—that casual greeting thrown at the Republican diner owner that showed that there simply could be no other choice this year—that showed the case proved, wrapped up, unassailable.

And yet what struck me in this little model of political art was a tiny riff the candidate effortlessly worked into it from his banter with the crowd. When Obama launched into his story with “Because I love pie,” a woman out in that sea of cheering, laughing people shouted back, ” I’ll make you pie, baby!” and to the general hooting laughter the candidate returned, “Oh yeah, you gonna make me pie?” Then, after a beat, amid even more raucous laughter, and several other female voices shouting out invitations, “You gonna make me sweet potato pie? ” More shouts and laughter. ” All you gonna make me pie?”

“Well you know I love sweet potato pie. And I think what we’re going to have to do here”—and the laughter and the shouting rose and as it did his voice rose above it—“what we’re going to have to do here is have a sweet potato pie contest.… That’s right. And in this contest, I’m gonna be the judge.” The laughter rose and you could hear not only the women but the deep laughter of the men taking delight in the double entendre that was not only about the women and their laughing, teasing offers and about their pie that that lanky confident smiling young man knew how to eat and enjoy and judge, but even more now, amazingly, as people came one by one to recognize, about something else. To those people gathered in Vernon Park that bright sun-drenched morning, it was an even more titillating and more pleasurable double entendre, for it was most clearly about something they’d never had but hoped and dreamed of having and now had begun to believe they were within the shortest of short distances of finally tasting. “Because you all know,” their candidate told them, “that I know sweet potato pie.”

2.

Two days later I made my way past the long lines of people moving slowly in the glare of the seaside sun, through the half-dozen brightly colored tables of McCain-Palin tchotchkes (“You’re going to a rally. You need a rally towel!” ), toward the glinting glass-skinned magnificence of the Virginia Beach Convention Center. The people moving in such good-natured and patient order were easy and handsome and prosperous, and if those in the urban precincts of Germantown had come to Senator Obama on foot in a vast pilgrimage of baby carriages and bicycles and skate boards, these enthusiasts for Senator John McCain and his superstar consort from Alaska, Governor Sarah Palin, came mostly in a glinting-bright armada of SUVs and pickup trucks and late-model sedans rolling in from the suburbs.

The crowd was white, blond, and well fed, with many sport shirts, much silver hair, and a good deal of makeup in evidence. Women were well coiffed, men well tanned, and everyone I spoke to unfailingly polite. But if the crowds in the two rallies were almost comically distinct and complementary, seeming to form a parody of the respective bases of the two political parties, both were plainly rooted in the middle class, with Obama’s urban followers shading downward, toward working class, and hoping to rise, and McCain’s suburbanites shading upward, toward the well-to-do, and fearing to fall. Like Obama, these confident and prosperous-looking men and women already had their sweet potato pie and did not want to lose it.

After the warm-up speeches delivered by the local politicians and after the entertainment, brought to you live by the inimitable brand-name voice and bearded, sun-glassed, cowboy-hatted figure of Hank (“Are You Ready for Some Football?! “) Williams Jr., who offered a memorable anthem to the stubborn survival of “true American values” in “Country Boy Can Survive”—

We say grace and we say ma’am

If they ain’t into that, we don’t give a damn.

And a country boy can survive….

—a pungent song of besieged resentment, determination, and transcendence lustily cheered by the several thousand SUV-driving country boys and girls in the hall, and later converted into more explicitly and topically political terms:

The left-wing liberal media has always been

A real close-knit family.

But most of the American people

Don’t believe ’em anyway, you see.

John and Sarah tell you just what they think

They’re not gonna blink,

And they don’t have radical friends

To whom their careers are linked….

After all this the McCains and the Palins mounted the stage, into an ocean of cheers and waving signs and chants. (” No Bama! No Bama! “) I was struck by the magnetic smiling beauty and charisma of Governor Palin—whose mix of proper white blouse, black skirt, and black glasses just failed to suppress and thus enhanced a pert, naughty-librarian sexiness of the sort evoked in a thousand Playboy photo spreads of the early Sixties—and by the crabbed, wounded, unavoidable physicality of John McCain. For this oft-proclaimed “most important election of our lifetimes,” some playful deity seems to have determined that the candidates shall serve as one another’s perfect mirror images: the first black major-party candidate versus the whitest of white men (“We need first of all to get McCain some sun,” one of his supporters joked mirthlessly to me afterward); the forty-seven-year-old versus the seventy-two-year-old (the widest difference in age—more than a generation—between presidential candidates in history); the cool lawyer-professor versus the daring naval aviator—and, above all, the young lithe basketball-playing athlete versus the crippled hero, the wounded Fisher King of the American post-Vietnam wasteland.

The prolonged suffering that determined McCain’s career is marked indelibly on his body. He is a politician who can’t make the gesture of embracing a crowd, who can’t even raise his arms. The burden of that acknowledgment is borne, inevitably, by his face, by his slightly uncomfortable smile and his endlessly blinking eyes. He does not seem at ease as the waves of applause flow over him. Obama’s frank pleasure, his gleeful imbibing of the crowd’s energy, is reflected here in the dark mirror of McCain’s inability to do what should be natural to any leader. Everyone in the hall knows the tale of how he was brutally deprived of it, McCain’s own Passion Story, chapter and verse.

Indeed, as the cheers rose, and even more after Palin’s call—“ Those of you who have served your country raise your hands! “—and the impenetrable forest of hands rose up in answer (leaving the press corps on its risers looking very isolated), it was clear not only that everyone here knew the story but that for them it meant something. Late the night before, driving from Philadelphia to Virginia Beach, I had listened again to a recording of McCain recounting it, intoning the horrors in a singsong, nearly affectless voice:

One guard would hold me while the others pounded away. Most blows were directed at my shoulders, chest and stomach. Occasionally, when I had fallen to the floor, they kicked me in the head. They cracked several of my ribs and broke a couple of teeth. My bad right leg [which had been broken, along with both arms, when he had ejected over Hanoi, and had never been set] was swollen and hurt the most of any of my injuries. Weakened by beatings and dysentery, and with my right leg again nearly useless, I found it almost impossible to stand.

On the third night, I lay in my own blood and waste, so tired and hurt that I could not move. The Prick came in with two other guards, lifted me to my feet, and gave me the worst beating I had yet experienced. At one point he slammed his fist into my face and knocked me across the room toward the waste bucket. I fell on the bucket, hitting it with my left arm, and breaking it again. They left me lying on the floor, moaning from the stabbing pain in my refractured arm.1

Oceana Air Station, a few miles up the road, had been McCain’s first duty station. The men and women here knew these beatings came in part because he had refused, unlike some others, to accept early release from the POW camp, and had refused, thus far, to sign a confession. To them McCain’s “story” and the campaign’s propensity to advert to it in order to deflect all criticism was not a running joke, as it had become for much of the press, but an unassailable monument to character and trustworthiness—notions that, they firmly believed, the “larger culture,” morally bankrupt as it now was, could acknowledge with nothing more than snickers. And when Rick Davis, McCain’s campaign manager, had said that “this election is not about issues. This election is about a composite view of what people take away from these candidates,” they had regarded this not as the scandalous self-revelation of a harshly negative Republican campaign which, devoid of ideas, had resorted to unremitting personal attacks, but as a simple, self-evident truth.

So his body, crabbed, restricted, frozen as if in a body cast, seemed a kind of talisman to this crowd, and they cheered him as he hobbled about the little stage. When later he uttered the “takeaway lines” of that particular day, the lines that were destined to be extracted and vacuumed up into the electronic ether by the several score cameras and recorders bristling around me and arrayed that evening before the hundreds of millions of fellow citizens—

We have 22 days to go. We’re six points down. The national media has written us off. Senator Obama is measuring the drapes, and planning with Speaker Pelosi and Senator Reid to raise taxes, increase spending, take away your right to vote by secret ballot in labor elections, and concede defeat in Iraq. But they forgot to let you decide. My friends, we’ve got them just where we want them !

—when he uttered those last words, bringing on a great explosion of laughter and applause, they meant something very specific to this well-heeled, largely ex-military crowd. They meant that you don’t give up the struggle, even though most of the weak “popular culture” crowd would. That you fight for what you have. That, as McCain shouted out to them with increasing vehemence as the cheering rose, “we have to change direction now and we have to fight and you know and I know how to do that. I’ve been fighting for this country since I was 17 and I have the scars to prove it….”

They cheered lustily at this, for if anything they wanted him to fight still harder. ” Take the Gloves Off or You Will Lose! ” read one hand-lettered sign, its young female bearer pumping it up and down urgently in front of the candidate’s face, and I heard this sentiment expressed repeatedly, that McCain must fight harder, using “everything he had.” If one pointed out that as the financial crisis had spread its fear and Obama’s lead in the polls had begun steadily to grow, McCain’s campaign had in fact turned increasingly harsh, that the vast majority of his advertisements, and now his “robocalls,” were attacks on Obama, most focusing on his “association” with, as McCain put it, the “washed-up old terrorist,” Weatherman founder and now education professor William Ayers—if one pointed all this out the answer came back from his frustrated and fearful supporters that this was simply not enough, not in an election where “everything was at stake.”

Where, they asked, were the ads featuring the Reverend Jeremiah Wright Jr. exhorting his First Trinity congregation, at the time Barack Obama’s congregation, with the call that “God damn America!” and with all those other horrible words? Had I not seen the videos of these awful sermons? If it was true, they said, that McCain’s honor now led him to forbid his campaign the use of this particular image (which Hillary Clinton, after all, had exploited in the Pennsylvania primary with great success), if it was true that his campaign advisers were even now pushing him to use Wright and that the candidate still “wouldn’t budge,” then what good had this vaunted honor really done him?2 After all, shouldered with a historic financial crisis and an incumbent president as unpopular as any in history, he had already “gone negative” some time ago, and his reputation had long since been tarnished among a press corps and a public increasingly disgusted by the persistent references to Ayers, among others. Why Ayers and not Wright?

This was, needless to say, a rather utilitarian definition of honor, something far from the code McCain, with whatever contradictions, seemed to embrace. To McCain the distinction was clear: on the one hand a “domestic terrorist” who had tried to undermine and destroy his beloved country at the very moment he was suffering for it; on the other, a black preacher shouting out his righteous anger to a black congregation, whom he, McCain, could not and would not attack in order to destroy the country’s first major-party black candidate—even if it meant losing the election. The first “association” was by his lights ignoble and unpatriotic and Obama should be held to account. The second—well, he had said he would not run a “racist” campaign and he would not.

That this distinction was lost not only on his opponents but on some of his more aggressive supporters, who in their bewilderment and fear saw le déluge approaching, was perhaps not surprising. Listening to these bitter words from this man in his red “McCain- Palin Country First” T-shirt, gazing over his shoulder at the white-haired candidate turning and lumbering about the stage with his arms stiffly extended at the waist, a haunting line of Kafka’s floated into my mind: “The condemned man has to have the law he has transgressed inscribed on his body.”3 Was that contradictory and confounding and self-aggrandizing sense of honor, marked as it was on his broken rigid body, the “honor” that led him to forswear the black preacher while flaunting the “broken-down terrorist,” to be McCain’s pride, his burden, and his tragedy all at once?

Later, out in the bright glare of the seaside light, as the crowds flowed back toward the endless parking lots, I spotted bouncing along the sidewalk one of the more innovative home-made signs—“The Obamanation Ends Here!” it declared in an admirable rainbow of handpainted colors—and I asked its smiling creator, a forty-four-year-old Air Force veteran named Brad Crum, what exactly he feared in “The Obamanation.”

“I think there’ll be a lot of moves toward socialism,” he told me, growing serious. “I’ve been all around the world, Spain, Germany”—he had served twenty-five years, as an electronics technician, and was about to start work for the FAA:

I’ve seen it. I know it doesn’t work. You hear what he’s been saying? Health care for everyone? Sounds good but taxes would have to be so high it wouldn’t be worth it.

I grew up in East Kentucky. I knew a lot of people there whose ambition was really in the end just to game the system. You know, to get a job and then get on the draw….

The people with him, including a woman carrying a “Gun Totin’ Lipstick Wearin’ Women 4 McCain/Palin” sign, nodded, a bit sheepishly. Just as their understanding of McCain was a deeply personal one—they knew him, understood what he represented and what he would protect them from—their sense of what Obama stood for was murky and dark, fearful. They were bewildered by him, mistrusted him: Where had he come from, after all? What had he ever done? What accomplishments did he have that could compare to what McCain had achieved, what he had suffered? McCain had served right here. His father and grandfather had been admirals. In Meridian, Mississippi, there was an air station, McCain Field, named for his grandfather. And who was…Barack Obama?

I thought for a moment of telling them about the Kansas grandparents and the years in Chicago. Then I remembered the recording of Obama’s rich voice filling the dark car as I sped down the interstate highway from Philadelphia the night before, reciting the litany from Dreams from My Father, when his Kenyan “Granny,” whom as a young man he seeks out in the upcountry town of Kisumu, tells him the story of his origins:

First there was Miwiru, It’s not known who came before. Miwiru sired Sigoma, Sigoma sired Owiny, Owiny sired Kisodhi, Kisodhi sired Ogelo, Ogelo sired Otondi, Otondi sired Obongo, Obongo sired Okoth, and Okoth sired Opiquo. The women who bore them, their names are forgotten, for that was the way of our people….4

We are a long way here from Virginia Beach—or rather, in any event, from white Virginia Beach—and even farther from the known and cherished formalities of the old military culture of McCain’s father in prewar Pearl Harbor:

Newly arrived officers, dressed in white uniforms, took their wives, who were attired in white gloves and hats, to call on the families of fellow officers every Wednesday and Saturday between four and six o’clock. The husband laid two calling cards on the receiving tray, one for the officer in residence and the other for the lady of the house. His wife offered a single card for her hostess, for it was inappropriate for an officer’s wife to call on another officer.5

One might have said, I suppose, that the evident differences here, as clear and glaring as black and white, masked many striking parallels—that here were two accomplished men obsessed with origins, with their fathers, men overshadowed by the myths of those who had sired them and with the worlds that they had made. Men who couldn’t help struggling with the past. One might even have pointed to more fortuitous crossing points—McCain’s sepia-colored Pearl Harbor, for example, a later version of which is also lodged firmly in the memories of Obama, who writes of the “appeal that the military bases back in Hawaii had always held for me as a young boy, with their tidy streets and well-oiled machinery, the crisp uniforms and crisper salutes.” It may not be white gloves and visiting cards, and the view of the young black outsider is not that of the young white admiral’s son; but given the litany of Granny in Kisumu, it is much closer than one might think possible.

Standing in the glaring sun, beads of sweat trickling down my face, with my friend holding his “The Obamanation Ends Here!” sign, I thought of offering these reflections and seeing what response they would bring. I held my tongue. They would think, I knew, that I had not been listening. They offered a simple and rough-hewn story. They had worked hard to get from East Kentucky to here. They had worked hard for what they had. Why should they let Obama, with his prettied-up socialism, open the door for others—others who had never worked as hard—to take a much easier route? Especially when that much easier route would be paved with their taxes, with the sacrifices that they and their families had already made? “Like my idea of community organizing,” Obama writes of the late Mayor Harold Washington of Chicago, “he held on to a promise of collective redemption.”

These people in the parking lot holding their homemade signs bleached by the sun did not believe in “collective redemption.” They believed in patriotism. And to them—unlike, perhaps, to those I had seen in Northwest Philly—“collective redemption” and “patriotism” meant very different things. Obama could talk and talk, spinning those long and beautiful sentences, reasoning so unassailably with that golden tongue (“He certainly has the symbolism down pat,” as one McCain supporter told me grimly); but whether he said so or not, what he really wanted to do was to take things away. They, too, knew their pie—and they feared they could see whose fingers were reaching for it now.

— October 23, 2008

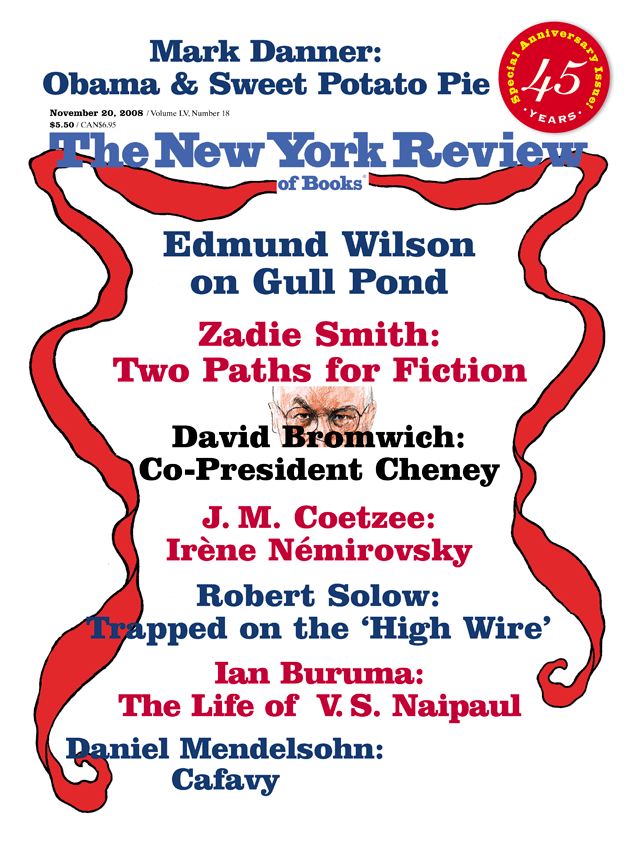

This Issue

November 20, 2008

The Co-President at Work

At Gull Pond

Two Paths for the Novel

-

1

See John McCain, with Mark Salter, Faith of My Fathers: A Family Memoir (Random House, 1999), pp. 242–243. ↩

-

2

See, for example, Tucker Carlson: “This spring, McCain said he wouldn’t use Wright as a campaign issue, and so far he’s stuck to that pledge…. The campaign hasn’t run a single ad featuring Wright, and neither have the RNC or pro-McCain 527s. Late last week, senior McCain advisers broached the topic with their candidate, but McCain wouldn’t budge.” “Bring Back Reverend Wright,” The Daily Beast, October 13, 2008. ↩

-

3

See Franz Kafka, “In the Penal Colony,” in Metamorphosis and Other Stories, translated by Michael Hofmann (Penguin Classics, 2007). ↩

-

4

See Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance (Three Rivers, 1995), p. 394. ↩

-

5

See McCain, Faith of My Fathers, p. 65. ↩