In response to:

The Lessons of the Master from the November 20, 2008 issue

To the Editors:

On Elizabeth Hardwick’s advice, “Never ever speak to them dear. They always get it wrong,” I did not cooperate with Patrick French’s book [The World Is What It Is: The Authorized Biography of V.S. Naipaul]; nor have I read it. There are a number of things wrong in Ian Buruma’s review of it [NYR, November 20, 2008].

Gillon Aitken was not dispatched to Buenos Aires checkbook in hand. (I wish he had been.)

There was one pregnancy and one that turned out not to be. I heard nothing about Pat raising the child.

The majority of my letters to Vidia were written because he had a habit of saying “please write me a little letter.” If he chose to leave them unopened, that was his business.

Not mentioned in Ian Buruma’s review is an error by Patrick French: no one has ever called me Margarita.

Vidia says I didn’t mind the abuse. I certainly did mind.

Margaret Murray

Buenos Aires, Argentina

To the Editors:

Ian Buruma tells us that he declined the invitation to write the life of V.S. Naipaul. Based on his review of Patrick French’s The World Is What It Is, I think we should all be glad of this.

Mr. Buruma does not say that Naipaul’s favorite word of contempt is “nigger.” But Mr. French makes this plain in his book, quoting Naipaul’s use of it on a number of occasions. In Mr. Buruma’s euphemistic telling, Naipaul’s “views…suggest a less than friendly attitude toward black people.” Naipaul’s viciousness and racism is never directly quoted, though there is plenty of it in the biography—and in Naipaul’s work. Mr. Buruma skirts the issue by calling this cruel man “fastidious and difficult,” ” piquant,” a “trickster,”…or an example of “bad boy behavior.”

And then there is “a most peculiar occasion”—the funeral of Patricia Naipaul, the hated and abused wife, whose decades of suffering at Naipaul’s hands are recorded by Mr. French. Naipaul had recently dumped his mistress of twenty-four years, had proposed marriage to someone he’d known a matter of months, indeed while his wife lay dying of cancer. And immediately after the cremation, Naipaul chitchats about the fineness of the white wine being served and rubbishes the culture of his new wife’s homeland (“barbarism”) as Mr. Buruma listens. “Most peculiar”? I would say appalling.

It is false and fatuous to say that Mr. French’s book represents “almost the invention of a new genre: the confessional biography.” There is no confession here, only inadvertence. It is an authorized biography by a persistent biographer that got out of hand. Mr. Buruma quotes Naipaul’s apparent disclosures, to support the myth of Naipaul’s candor. The real news in the book is that Pat Naipaul was able to speak from beyond the grave in the form of twenty-four notebooks kept over a period of twenty-odd years in which she closely documented her husband’s infidelities, screaming fits, hypocrisies, and his physical and mental abuse of her—which all of us who knew him were well aware of but were restrained from publishing by Naipaul’s lawyers. There is no proof in Mr. French’s book that Naipaul had ever read these journals; he held his wife in such low esteem that it is unlikely that he would have read them. Mr. French found the journals quite by chance in boxes that were sold by the pound by Naipaul to the University of Tulsa and “closed to public access.”

By characterizing the book as confessional, and saying “the truth is not skimped in Patrick French’s excellent book,” Mr. Buruma gives the impression that this biography is exhaustive. It is an extremely good book but there is more to say—if anyone had the stomach for it. There are many people who knew Naipaul well who were not interviewed by Mr. French (either refused to or were deceased), important among them his brother Shiva; Shiva’s widow, Jenny Naipaul; Derek Walcott; and his longtime (and later rejected) friend, Lawrence O’Keefe.

Mr. Buruma calls my book Sir Vidia’s Shadow a “rather bitter memoir.” He is entitled to his opinion. I think of it as an unsparing and accurate portrait of the man, minus the instances of racism and physical abuse that I was forbidden by lawyers to publish. Mr. Buruma speaks of Naipaul’s “great modesty.” In thirty years of knowing the man I was never privileged to observe this. I mainly saw his sadness, his tantrums, his envy, his meanness, his greed, and his uncontrollable anger. But I never saw Naipaul attack anyone stronger than himself; he talked big and insultingly but when he lashed out it was always against the weak—women who loved him, his wife, and waiters: people who couldn’t hit back, the true mark of the coward.

Advertisement

Naipaul’s lover, partner, and traveling companion of twenty-four years, Margaret Murray, refused to speak to Mr. French. She has not given any interviews nor has she spoken publicly about Naipaul. Ms. Murray was—even Naipaul says so—the most important woman in Naipaul’s life, his driver, his cook, his sexual and emotional support, the object of his desire and his sadism—for Naipaul pretty much the same thing, as the biography makes painfully clear. Ms. Murray’s letters to Naipaul are paraphrased by Mr. French. As a woman in love, she is misrepresented by such letters, which are abject and craving attention from Naipaul, who abused his wife but refused to divorce her. The hundreds of letters that Naipaul wrote to Ms. Murray have not been seen by Mr. French, nor by anyone but Ms. Murray. The result is not exactly Hamlet without the prince but it is certainly Hamlet without Ophelia.

Paul Theroux

Haleiwa, Hawaii

Ian Buruma replies:

That the wounds inflicted by V.S. Naipaul on people who loved him are still tender is amply demonstrated by the letters above. Margaret Murray has every reason to feel hurt, yet writes with a tone of fortitude and even a hint of flinty humor. Paul Theroux merely sounds bilious. There is something odd about this. If Naipaul was quite the monster he describes, why did Mr. Theroux spend decades of his life fawning over him, to the point, in Patrick French’s words, of offering, in his letters, “racist jokes and titbits of praise”?

But then the demolition of an idol by a disillusioned worshiper is never an edifying sight, and in the case of an aging writer a trifle undignified too.

I cannot presume to argue with Ms. Murray about her past. With one exception, the statements she disputes were made by V.S. Naipaul or Patrick French. I certainly never referred to her as Margarita. She would not have been aware of plans to have her child raised by Pat, because Naipaul never informed her of them. In French’s account, he discussed this possibility with relative strangers at a dinner party in New Zealand.

One error however is absolutely mine, for which I am sorry. French does not state that Naipaul’s agent Gillon Aitken flew to Buenos Aires to sort out his client’s private financial obligations. He claims this transaction took place in London. But this, too, is disputed by Margaret Murray, who surely knows best.

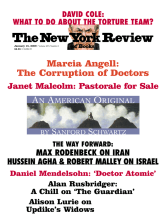

This Issue

January 15, 2009