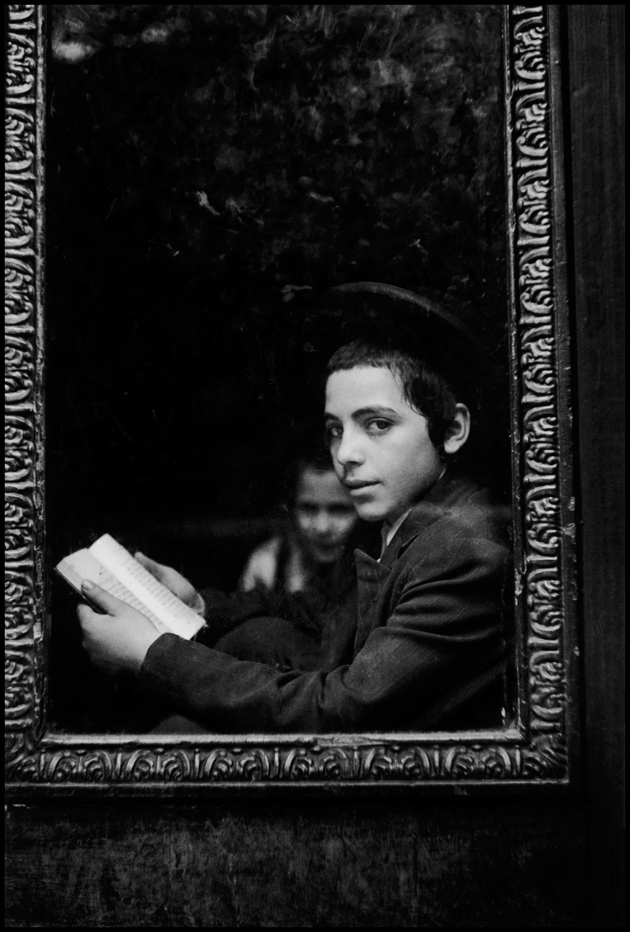

I never knew Toni Avegael. She was born in Antwerp in February 1926 and lived there most of her life. We were related: she was my father’s first cousin. I well remember her older sister Lily: a tall, sad lady whom my parents and I used to visit in a little house somewhere in northwest London. We have long since lost touch, which is a pity.

I am reminded of the Avegael sisters (there was a middle girl, Bella) whenever I ask myself—or am asked—what it means to be Jewish. There is no general-purpose answer to this question: it is always a matter of what it means to be Jewish for me—something quite distinct from what it means for my fellow Jews. To outsiders, such concerns are mysterious. A Protestant who does not believe in the Scriptures, a Catholic who abjures the authority of the Pope in Rome, or a Muslim for whom Muhammad is not the Prophet: these are incoherent categories. But a Jew who rejects the authority of the rabbis is still Jewish (even if only by the rabbis’ own matrilineal definition): who is to tell him otherwise?

I reject the authority of the rabbis—all of them (and for this I have rabbinical authority on my side). I participate in no Jewish community life, nor do I practice Jewish rituals. I don’t make a point of socializing with Jews in particular—and for the most part I haven’t married them. I am not a “lapsed” Jew, having never conformed to requirements in the first place. I don’t “love Israel” (either in the modern sense or in the original generic meaning of loving the Jewish people), and I don’t care if the sentiment is reciprocated. But whenever anyone asks me whether or not I am Jewish, I unhesitatingly respond in the affirmative and would be ashamed to do otherwise.

The ostensible paradox of this condition is clearer to me since coming to New York: the curiosities of Jewish identity are more salient here. Most American Jews of my acquaintance are not particularly well informed about Jewish culture or history; they are blithely ignorant of Yiddish or Hebrew and rarely attend religious ceremonies. When they do, they behave in ways that strike me as curious.

Shortly after arriving in New York, I was invited to a bar mitzvah. On my way to the synagogue, I realized I had forgotten my hat and returned home to recover it—only to observe that almost no one else covered his head during the brief, exiguous excuse for a religious ceremony. To be sure, this was a “Reform” synagogue and I should have known better: Reform Jews (known in England as “liberals”) have been optionally topless in synagogue for over half a century. All the same, the contrast between unctuous performance of ritual and selective departure from established traditions struck me then and strikes me now as a clue to the compensatory quality of American Jewish identity.

Some years ago I attended a gala benefit dinner in Manhattan for prominent celebrities in the arts and journalism. Halfway through the ceremonies, a middle-aged man leaned across the table and glared at me: “Are you Tony Judt? You really must stop writing these terrible things about Israel!” Primed for such interrogations, I asked him what was so terrible about what I had written. “I don’t know. You may be right—I’ve never been to Israel. But we Jews must stick together: we may need Israel one day.” The return of eliminationist anti-Semitism was just a matter of time: New York might become unlivable.

I find it odd—and told him so—that American Jews should have taken out a territorial insurance policy in the Middle East lest we find ourselves back in Poland in 1942. But even more curious was the setting for this exchange: the overwhelming majority of the awardees that evening were Jewish. Jews in America are more successful, integrated, respected, and influential than at any place or time in the history of the community. Why then is contemporary Jewish identity in the US so obsessively attached to the recollection—and anticipation—of its own disappearance?

Had Hitler never happened, Judaism might indeed have fallen into deliquescence. With the breakdown of Jewish isolation in the course of the later nineteenth century throughout much of Europe, the religious, communitarian, and ritualistic boundaries of Judaism were eroding: centuries of ignorance and mutually enforced separation were coming to a close. Assimilation—by migration, marriage, and cultural dilution—was well underway.

In retrospect, the interim consequences can be confusing. In Germany, many Jews thought of themselves as Germans—and were resented for just that reason. In Central Europe, notably in the unrepresentative urban triangle of Prague-Budapest-Vienna, a secularized Jewish intelligentsia—influential in the liberal professions—established a distinctive basis for postcommunitarian Jewish life. But the world of Kafka, Kraus, and Zweig was brittle: dependent upon the unique circumstances of a disintegrating liberal empire, it was helpless in the face of the tempests of ethnonationalism. For those in search of cultural roots, it offers little beyond regret and nostalgia. The dominant trajectory for Jews in those years was assimilation.

Advertisement

I can see this in my own family. My grandparents came out of the shtetl and into unfriendly alien environments—an experience that temporarily reinforced a defensive Jewish self-awareness. But for their children, those same environments represented normal life. My parents’ generation of European Jews neglected their Yiddish, frustrated the expectations of their immigrant families, and spurned communitarian rituals and restrictions. As late as the 1930s, it was reasonable to suppose that their own children—my generation—would be left with little more than a handful of memories of “the old country”: something like the pasta-and-St.-Patrick’s-Day nostalgia of Italian-Americans or Irish-Americans, and with about as much meaning.

But things turned out differently. A generation of emancipated young Jews, many of whom had fondly imagined themselves fully integrated into a post-communitarian world, was forcibly re-introduced to Judaism as civic identity: one that they were no longer free to decline. Religion—once the foundation of Jewish experience—was pushed ever further to the margin. In Hitler’s wake, Zionism (hitherto a sectarian minority preference) became a realistic option. Jewishness became a secular attribute, externally attributed.

Ever since, Jewish identity in contemporary America has had a curious dybbuk-like quality: it lives on by virtue of a double, near-death experience. The result is a sensitivity to past suffering that can appear disproportionate even to fellow Jews. Shortly after publishing an essay on Israel’s future, I was invited to London for an interview with The Jewish Chronicle—the local Jewish paper of record. I went with trepidation, anticipating further aspersions upon my imperfect identification with the Chosen People. To my surprise, the editor turned off the microphone: “Before we start,” she began, “I’d like to ask you something. How can you stand to live among those awful American Jews?”

And yet, maybe those “awful American Jews” are onto something despite themselves. For what can it mean—following the decline of faith, the abatement of persecution, and the fragmentation of community—to insist upon one’s Jewishness? A “Jewish” state where one has no intention of living and whose intolerant clerisy excludes ever more Jews from official recognition? An “ethnic” membership criterion that one would be embarrassed to invoke for any other purpose?

There was a time when being Jewish was a lived condition. In the US today, religion no longer defines us: just 46 percent of Jews belong to a synagogue, only 27 percent attend at least once a month, and no more than 21 percent of the synagogue members (10 percent of the whole) are Orthodox. In short, the “old believers” are but a minority.1 Modern-day Jews live on preserved memory. Being Jewish largely consists of remembering what it once meant to be Jewish. Indeed, of all the rabbinical injunctions, the most enduring and distinctive is Zakhor!—Remember! But most Jews have internalized this injunction without any very secure sense of what it requires of them. We are the people who remember…something.

What, then, should we remember? Great-grandma’s latkes back in Pilvistock? I doubt it: shorn of setting and symbols, they are nothing but apple cakes. Childhood tales of Cossack terrors (I recall them well)? What possible resonance could these have to a generation who has never known a Cossack? Memory is a poor foundation for any collective enterprise. The authority of historical injunction, lacking contemporary iteration, grows obscure.

In this sense, American Jews are instinctively correct to indulge their Holocaust obsession: it provides reference, liturgy, example, and moral instruction—as well as historical proximity. And yet they are making a terrible mistake: they have confused a means of remembering with a reason to do so. Are we really Jews for no better reason than that Hitler sought to exterminate our grandparents? If we fail to rise above this consideration, our grandchildren will have little cause to identify with us.

In Israel today, the Holocaust is officially invoked as a reminder of how hateful non-Jews can be. Its commemoration in the diaspora is doubly exploited: to justify uncompromising Israelophilia and to service lachrymose self-regard. This seems to me a vicious abuse of memory. But what if the Holocaust served instead to bring us closer, so far as possible, to a truer understanding of the tradition we evoke?

Here, remembering becomes part of a broader social obligation by no means confined to Jews. We acknowledge readily enough our duties to our contemporaries; but what of our obligations to those who came before us? We talk glibly of what we owe the future—but what of our debt to the past? Except in crassly practical ways—preserving institutions or edifices—we can only service that debt to the full by remembering and conveying beyond ourselves the duty to remember.

Advertisement

Unlike my table companion, I don’t expect Hitler to return. And I refuse to remember his crimes as an occasion to close off conversation: to repackage Jewishness as a defensive indifference to doubt or self-criticism and a retreat into self-pity. I choose to invoke a Jewish past that is impervious to orthodoxy: that opens conversations rather than closes them. Judaism for me is a sensibility of collective self-questioning and uncomfortable truth-telling: the dafka-like2 quality of awkwardness and dissent for which we were once known. It is not enough to stand at a tangent to other peoples’ conventions; we should also be the most unforgiving critics of our own. I feel a debt of responsibility to this past. It is why I am Jewish.

Toni Avegael was transported to Auschwitz in 1942 and gassed to death there as a Jew. I am named after her.

—This piece is part of a continuing series of memoirs by Tony Judt.