On October 8, Liu Xiaobo became the first Chinese to receive the Nobel Peace Prize and one of only three winners ever to receive it while in prison. The Oslo committee had already received a warning from Beijing not to give Liu the prize because he was a “criminal,” serving eleven years for “subversion of state power.” After Oslo made its announcement, Beijing labeled the award an “obscenity.” By Beijing’s standards it certainly is. Charter 08, a document that Liu helped write—and that was published in English for the first time in the January 15, 2009, issue of The New York Review1—was soon signed by ten thousand Chinese. It demanded that

We should make freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and academic freedom universal, thereby guaranteeing that citizens can be informed and can exercise their right of political supervision. These freedoms should be upheld by a Press Law that abolishes political restrictions on the press. The provision in the current Criminal Law that refers to “the crime of incitement to subvert state power” must be abolished. We should end the practice of viewing words as crimes.

The petition also said, “We must abolish the special privilege of one party to monopolize power and must guarantee principles of free and fair competition among political parties.”

Words can be fatal in China. Zhang Zhixin, a young Chinese woman, was executed in 1975 for “opposing the Great Helmsman Chairman Mao, opposing Mao Zedong thought, opposing the revolutionary proletarian line and piling offense upon offense.” To ensure that Zhang could not cry out at her execution, her vocal cords were cut.

In May 1989, in Tiananmen Square, I saw the then-thirty-three-year-old Liu, a university teacher, exhorting students to demand democracy above all, in addition to their calls for free speech and an end to corruption. On the night of June 4, Liu helped broker a deal with the army that permitted the last protesters in the square to escape the slaughter that had already taken hundreds of lives. He was immediately imprisoned for twenty months as a “black hand.” After his release Liu said, “I hope to be a sincere Chinese intellectual and writer. This can put me back into prison—which is what happens to people like me in China.”

It is indeed words that have put Liu back behind bars. Chinese state television went black before Oslo spoke. But enthusiastic crowds gathered outside Liu’s house in Beijing. If nothing else, the Prize ensures that, unlike Zhang Zhixin, Liu will not disappear in prison. Despite every effort to cow Oslo and silence Liu Xiaobo, Beijing has failed, and millions of Chinese will cheer. But within twenty-four hours of the award to Liu, twenty-four human rights activists were detained. Many others have been placed under house arrest, including Liu’s wife. She said that after she saw her husband and informed him that he had won the prize, he wept and said, “This is for the Tiananmen martyrs.”

This Issue

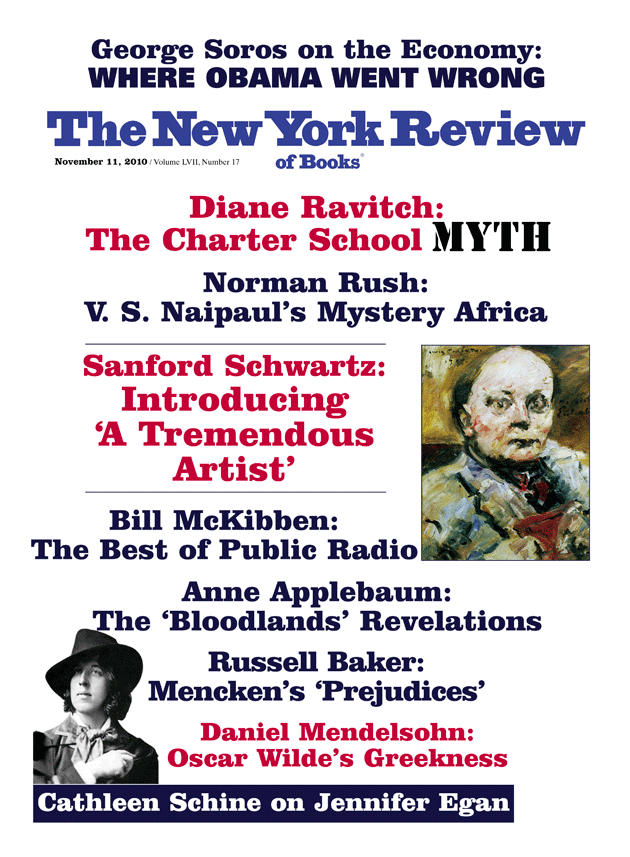

November 11, 2010

-

*

See Perry Link’s article in that issue, and subsequent correspondence and commentary in the issues of April 30, May 28, and August 15, 2009. See also Perry Link’;s blog posts on Liu Xiaobo and Charter 08 posted on December 21, 2009, and January 27, 2010. ↩