The essential facts of Osama bin Laden’s demise—that he was shot dead by US Navy SEALs in a house in Abbottabad, Pakistan, during the early hours of May 2, 2011, local time—have been reliably established and stand beyond reasonable doubt. For many Americans and victims of al-Qaeda’s violence worldwide, they are the only facts that will ever matter. Bin Laden planned and funded terrorism operations that killed many hundreds of civilians not only in New York and Washington, D.C., on September 11, 2001, but also in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

Given his record, it is uncomfortable to suggest that there might be more to the subject of bin Laden’s killing than a straightforward story of justice delivered. And yet from the first hours after the Abbottabad raid, American government officials have made false, confusing, and incomplete public statements about what, exactly, happened at Abbottabad. They have also dissembled about how Operation Neptune Spear, as the raid was named, planned for the possibility that bin Laden might be taken alive and put on trial.

Mark Owen, a pseudonym used by a recently retired SEAL named Matt Bissonnette, was a team leader on the Abbottabad raid. In No Easy Day, he writes that he hopes “to set the record straight about one of the most important missions in US military history.” His book belongs to an expanding genre of memoirs by Special Forces veterans and retired Central Intelligence Agency operatives. The genre’s growth may seem incongruous with the imperative of secrecy in intelligence activity and in the work of elite, clandestine military units like the SEALs. Yet the recent memoir boom seems to have been encouraged by military and intelligence leaders. This is presumably because, besides adding to the historical record, such books enhance the global brands of the CIA and the Special Forces, and so they help in the recruiting and retention of spies and operatives, while glamorizing the agencies in ways that make it difficult for members of Congress to cut their budgets.

Typically, the authors of such memoirs submit their manuscripts before publication for official review, to scrub the works of classified information. Bissonnette declined to do so; he writes that he eliminated all secret information from his book on his own. The Pentagon has declared that Bissonnette is in breach of his legal obligations, but so far the government has taken no action against him. No Easy Day is in any event respectful about the Obama administration and friendly to the SEALs, promoting their accomplishments enthusiastically. It also offers many new and apparently reliable eyewitness details about bin Laden’s last minutes. It would be too much, however, to say that Bissonnette has set the record straight.

For one thing, the story of how bin Laden’s hideout was discovered and who protected the fugitive during the last decade of his exile remains riddled with holes and gaps. From the mid-1990s, the CIA led the effort to find bin Laden; a team of analysts, many of them women, persisted painstakingly until a few disparate clues about one of bin Laden’s couriers came together and the courier was located in Pakistan, according to the version given by the Obama administration after Neptune Spear and illuminated in reportorial depth by the journalist Peter Bergen in his recent book, Manhunt.1 Bissonnette writes of a female CIA analyst who traveled with the SEAL team to Afghanistan and told them she was “one hundred percent” sure they would find bin Laden at Abbottabad; she cried when the SEALs returned from the raid with his body.

Bissonnette has said that Neptune Spear’s authors at the Pentagon and in the White House, including President Obama, regarded capturing bin Laden alive as a desirable and serious goal, when the facts suggest that such planning was a thin fig leaf for an operation meant to kill, a fig leaf created mainly for appearances’ sake, on the advice of clever and careful lawyers. Why do the misleading statements and interpretive dissonance surrounding Operation Neptune Spear matter? The raid seems certain to join the likes of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination and Adolf Hitler’s suicide as a staple of popular and even scholarly history; it would be useful not to seed the initial record with errors and misunderstanding. More importantly, the mission illuminates America’s wider, continuing system of secret, violent counterterrorist operations in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and elsewhere—a high-tempo regime of drone strikes, night raids, and detention practices that is largely unaccountable to the public and draped in secrecy rules.

One disturbing aspect of the system involves the failure of the Obama administration and Congress to close the prison at Guantánamo Bay or to create adequate political support for putting terrorists on trial as criminals. This has gradually led Obama’s White House to discover that “killing was a lot easier than capturing,” as the journalist Daniel Klaidman puts it succinctly in Kill or Capture,2 his important and revelatory chronicle of the administration’s internal arguments about the legal and ethical dilemmas of counterterrorism.

Advertisement

Neptune Spear must be understood in the wider setting Klaidman describes. Capturing terrorism suspects and delivering them to courtrooms became a declining priority during Obama’s first term. Few Americans may regret Osama bin Laden’s death, but more of them might be dismayed by some of the assumptions and bureaucratic habits of the counterterrorism regime that brought the al-Qaeda leader down.

The first public impression created of bin Laden’s killing was that of an Old West shootout: an outlaw, cornered, raised his gun against an arriving cavalry and was shot down. On Sunday night, May 1, 2011, Eastern Daylight Time, President Obama announced the news on national television. He said bin Laden had been killed “after a firefight.” Other administration officials, speaking that night on condition that they would not be named, said that bin Laden personally had resisted the attack, and they implied that he had wielded a weapon. These briefings led The New York Times, the national paper of record, to publish a main story whose first paragraph declared that bin Laden “was killed in a firefight with United States forces…. American officials said Bin Laden resisted and was shot in the head.”

The next afternoon, John Brennan, the assistant to the president for homeland security and counterterrorism, provided an on-the-record press briefing about the raid. No Easy Day makes clear that at the time Brennan spoke, few of the seventy-nine men who had participated in the mission had yet provided detailed accounts to their superiors of what they saw and did. This apparently explains why Brennan made a number of false statements at his briefing. Brennan also seemed determined to emphasize details that would diminish bin Laden’s worldwide reputation at the provocative moment of his killing.

Brennan said that bin Laden “was engaged in a firefight with those that entered the area of the house he was in. And whether or not he got off any rounds, I quite frankly don’t know.” He added that there was “a female who…was used as a shield to shield bin Laden from the incoming fire.” Brennan identified the woman as one of bin Laden’s wives. “She served as a shield,” he said. “Again, this is my understanding—and we’re still getting the reports back of exactly what happened.”

Brennan nonetheless extrapolated from the uncertain reports to make a larger point: “Here is bin Laden…hiding behind women who were put in front of him as a shield. I think it really just speaks to just how false his narrative has been over the years.”

Four days later, the White House corrected many of Brennan’s statements. Bin Laden had not been armed when he was killed, administration spokesmen conceded. He had not used any woman as a shield. Nor had there been a “firefight” in the house where he lived.

No Easy Day provides a clarifying, convincing account of how the shooting actually unfolded. The SEALs’ carefully rehearsed raid plan, overseen from the White House, was disrupted at the start. One of the two helicopters carrying the assault team crash-landed. The pilots of the second helicopter then landed in a different place from where they had originally intended. This led the SEALs to improvise as they carried out their assault.

Early on, Bissonnette and a colleague approached an outbuilding where they believed Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, a courier associated with bin Laden, might be residing with his family. The two SEALs pounded on the door with a sledgehammer. Someone fired out—this was the only hostile shooting the SEALs received during the entire raid. Bissonnette and his colleague, who spoke Arabic, shot back and appeared to kill a man who turned out to be al-Kuwaiti.

Immediately after this nerve-jangling exchange of gunfire, al-Kuwaiti’s wife called out from inside the building. She unlocked the door and walked out. Bissonnette recalls:

I could just make out the figure of a woman in the green glow of my night vision goggles. She had something in her arms and my finger slowly started applying pressure to my trigger. I could see our lasers dancing around her head. It would only take a split second to end her life if she was holding a bomb.

As the door continued to open, I saw that the bundle was a baby.

Bissonnette and his colleague admirably held fire. Three children trailed the woman into the courtyard and the SEALs ushered them to one side. The SEALs went inside, found al-Kuwaiti on the floor, and “squeezed off several rounds to make sure he was down.” But this initial exchange of fire suggested that they should expect violence as the assault proceeded, in Bissonnette’s telling.

Advertisement

Another team of SEALs now entered the first floor of the main house. One of them spotted al-Kuwaiti’s brother, Abrar, as he poked his head into a hallway. They shot him, followed him into a side room, and shot him again as he was “struggling” while lying on the floor. During this sequence, according to Bissonnette, Abrar’s wife “jumped in the way to shield him” and the SEALs shot her dead, too.

Bissonnette then joined a line of colleagues as they climbed the stairs of the main house. On the second floor, a team member in front of him preemptively shot dead bin Laden’s son, Khalid. As Bissonnette stepped past the body, he saw an AK-47 assault rifle propped nearby. “We had planned for more of a fight,” he writes. Later, when they inspected Khalid’s assault rifle, they found a round in the chamber. Khalid “was prepared to fight, but in the end, he hadn’t gotten much of an opportunity.”

Bissonnette continued up toward the third floor. There was another SEAL in front of him; he could not see around the point man very well. Near the top of the stairs, he heard the distinctive sound of firing from the lead SEAL’s rifle, which was equipped with a silencer. “The point man had seen a man peeking out of the door on the right side of the hallway…. I couldn’t tell from my position if the rounds hit the target or not. The man disappeared into the dark room.”

They went inside and found “two women standing over a man lying at the foot of a bed.” The man on the floor was bin Laden, although the SEALs did not know that for certain then, Bissonnette writes. He recounts how the attack ended:

The point man’s shots had entered the right side of [bin Laden’s] head. Blood and brains spilled out of the side of his skull. In his death throes, he was still twitching and convulsing. Another assaulter and I trained our lasers on his chest and fired several rounds. The bullets tore into him, slamming his body into the floor until he was motionless.

Bin Laden, then, was the third of three men the SEALs shot dead, or finished off, while they were lying on the floor. Perhaps al-Kuwaiti, Abrar, and bin Laden had been mortally wounded by the initial shots that struck them, but no effort was made to determine their prospects for survival. Bin Laden had stored a gun on a shelf nearby but it contained no ammunition; there has been no evidence that he tried to get hold of it; he was neither armed nor aggressive at the moment of his death.

Bissonnette offers no direct explanation for the additional shooting of the downed men, but he implies that the action is a standard SEAL tactic motivated by self-defense. Evidently, the protocols for the Abbottabad raid instructed the assaulters to assume that any wounded men they encountered might be able to trigger a suicide explosive vest or wield a hidden weapon, and so the SEALs were authorized or even encouraged to shoot wounded men until they were dead.

No Easy Day makes clear, however, that the protocols also encouraged the SEALs to show restraint toward women and children, even though it would be reasonable to assume that the wives of a radical like bin Laden might be dangerous—al-Qaeda has sponsored female suicide bombers and bin Laden’s wives included well-educated and feisty women who might well have chosen to shoot back on their own accord. It seems likely that President Obama ordered the SEALs to assume any men they encountered would be implacably dangerous and should be preemptively killed at the slightest provocation, but that he also asked the SEALs to spare the women where possible. If these were indeed the orders, the SEALs followed them under pressure with professional precision. Bissonnette does not discuss in detail what orders he had.

A number of Obama’s cabinet members and advisers said publicly after the raid that they were prepared to take bin Laden into custody, if it were possible to do so. No Easy Day adds emphasis to this claim. During a recent interview broadcast on 60 Minutes, the CBS correspondent Scott Pelley asked Bissonnette, “Was the plan to kill Osama bin Laden or capture him?” His question elicited the following exchange:

Bissonnette: This was absolutely not a kill-only mission. It was made very clear to us throughout our training for this that, “Hey, if given the opportunity, this is not an assassination. You will capture him alive, if feasible.”

Pelley: That was the preferred thing?

Bissonnette: Yes.

Pelley: To take him alive, if you could?

Bissonnette: Yeah, yeah. I mean, we’re not there to assassinate somebody. We weren’t sent in to murder him. This was, “Hey, kill or capture.”

This claim that capturing bin Laden was “the preferred thing” is not easy to reconcile with the on-site decision to shoot bullets into his writhing body. Nor is it easy to reconcile with the declaration by Obama’s attorney general, Eric H. Holder Jr., when he was asked in 2010 if the United States might ever find itself in the position of offering constitutional legal protections to bin Laden. Holder said, “You’re talking about a hypothetical that will never occur. The reality is that we will be reading Miranda rights to the corpse of Osama bin Laden.”

At his press briefing on May 2, John Brennan said the question of whether to kill or capture bin Laden had been discussed “extensively in a number of meetings in the White House and with the president” during the mission’s planning. Obama decided to prepare for the possibility of bin Laden’s capture, but only if “he didn’t present any threat,” Brennan recounted. “The president put a premium on making sure that our personnel were protected and we were not going to give bin Laden or any of his cohorts the opportunity to carry out lethal fire on our forces.” And yet, “if we had the opportunity to take bin Laden alive…the individuals involved were able and prepared to do that.”

During the past decade, in my own discussions with American counterterrorism policymakers and intelligence analysts, I have heard many officials in the George W. Bush and the Obama administrations state that it would be better, as a matter of counterterrorism policy, to kill bin Laden, rather than to capture him and put him on trial, whether in a federal courtroom or before a military commission. These officials feared the provocative spectacle of a bin Laden trial and particularly the violent attacks it might induce.

Clearly, killing bin Laden outright was a formal policy of the George W. Bush administration. President Bush said publicly that he wanted bin Laden “dead or alive.” Yet Cofer Black, the director of the Counterterrorism Center at the CIA at the time of the September 11 attacks, acting on Bush’s instructions, told the first CIA operatives dispatched to Afghanistan to hunt for bin Laden, as the leader of that mission recalled it:

I want to give you your marching orders, and I want to make them very clear…. I don’t want bin Laden and his thugs captured, I want them dead. Alive and in prison here in the United States, they’ll become a symbol, a rallying point for other terrorists…. They must be killed. I want to see photos of their heads on pikes. I want bin Laden’s head shipped back in a box filled with dry ice. I want to be able to show bin Laden’s head to the president. I promised him I would do that.3

President Obama, in contrast, never said publicly whether he favored putting bin Laden on trial or killing him. In early 2009, in a speech at the National Archives, Obama announced that he would end the policy of using interrogation methods judged to be torture by the International Red Cross, and that he would close Guantánamo’s prison. He indicated that he would be open to trying some terrorists before military commissions, rather than dispatching all of Guantánamo’s inmates to federal courtrooms, but he declared that we “cannot keep this country safe unless we enlist the power of our most fundamental values.” He promised policies based on “an abiding confidence in the rule of law and due process.” He added that “fidelity to our values” is the “reason why enemy soldiers have surrendered to us in battle, knowing they’d receive better treatment from America’s Armed Forces than from their own government.”

In the years since, the president has struggled to live up to those pledges. In the one case where he took a major political risk to try a high-profile al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorist in federal court, his decision ended badly. In late 2009, on the recommendation of Attorney General Holder, Obama ordered Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the bin Laden ally who masterminded the September 11 attacks, transferred from Guantánamo to stand trial in the Southern District of New York. Republicans accused Obama of going soft and whipped up a political backlash that forced the president to retreat; Mohammed is now facing a trial before a military commission at Guantánamo.

In planning for Abbottabad, White House lawyers would almost certainly have assured Obama that it would be legal to kill bin Laden outright. The “Authorization for the Use of Military Force” enacted by Congress a week after the September 11 attacks provided for the use of deadly force against al-Qaeda’s leaders. Also, under international and American laws arising from the rights of self-defense, if a terrorist is actively planning deadly operations, it can be legal to strike first. We know from White House disclosures that Obama seriously considered bombing the Abbottabad compound to smithereens. He demurred out of concern that it might not be clear after the attack whether bin Laden had been there at all. Yet if the president had decided on bombing, he would surely have justified his decision by pointing to the principles of self-defense, just as he uses this doctrine to justify the dozens of drone strikes he has authorized against suspected militants in countries where the United States is not formally at war.

The Abbottabad raid, as it was ultimately designed, seems to have brought into play different questions of international and American law concerning the requirement of soldiers to accept surrenders when they are offered. Having chosen to go in on the ground, Obama evidently did not wish to design a mission that precluded the theoretical possibility that bin Laden might surrender. Instead, he approved rules of engagement that made bin Laden’s surrender all but impossible.

As the SEALs prepared, Bissonnette writes, a lawyer from either the Department of Defense or the White House instructed them, speaking of bin Laden, “If he is naked with his hands up, you’re not going to engage him. I’m not going to tell you how to do your job. What we’re saying is if he does not pose a threat, you will detain him.” Klaidman, too, quotes a Pentagon official as saying, after the fact, “The only way bin Laden was going to be taken alive was if he was naked, had his hands in the air, was waving a white flag, and was unambiguously shouting, ‘I surrender.’”

What if, however improbably, bin Laden had done this? Obama’s team apparently planned to hold him on a US Navy ship at sea for a number of weeks and interrogate him about any active terrorist plots he might know about. After that, the administration probably would have shipped bin Laden to Guantánamo, reversing its policy to accept no new prisoners at that discredited facility.

This fantastical-sounding plan reflects upon the broader counterterrorism system’s current paralysis over the detention of suspects. Klaidman describes a telling example, little examined, that occurred at the same time as the Obama administration planned for Abbottabad. On April 19, 2011, Navy SEALs boarded a fishing boat in the Gulf of Aden and arrested Ahmed Abdulkadir Warsame, a British-educated, alleged liaison between the al-Qaeda affiliate in Yemen and al-Shabab, the militant group in Somalia. Warsame was an alleged gunrunner who knew about transnational terrorism plots; he was also “the first significant terrorist captured overseas since Obama had become president,” as Klaidman reports.

The SEALs transferred Warsame to the USS Boxer, which had been “outfitted as a kind of floating prison.” For the next two months—before and after the Abbottabad raid—the White House held “no less than a dozen secret principals or deputies meetings to resolve the case.”

They could not decide what to do with Warsame, however. If they put him on trial in federal court in New York, they would invite a repeat of the Khalid Sheikh Mohammed debacle, on the cusp of an election year. Yet if they put Warsame on trial before a military commission in a navy brig or at Guantánamo, they would signal to “the left and civil libertarians that the administration had given up on its commitment to using civilian courts to enforce the laws against terrorists…. It was no accident that Warsame was Obama’s only major capture,” Klaidman concludes, because the prolonged stalemate about what to do with him proved the rule that killing terrorist suspects was much easier than shouldering the political risks of putting them on trial.

In the end, the Obama administration secretly held Warsame at sea for seventy days, then transferred him to face criminal trial in New York federal court. As Brennan put it during the final deliberations, after Abbottabad, according to Klaidman: “We’ve proved we can kill terrorists. Now we have to prove we can capture them consistent with our values.”

Klaidman judges the outcome “textbook Obama…nuanced and lawyerly.” But the nuances obscure an obvious conclusion: the Obama administration’s terrorist-targeting and detention system is heavily biased toward killing, inconsonant with constitutional and democratic principles, and unsustainable. The president has become personally invested in a system of targeted killing of dozens of suspected militants annually by drone strikes and Special Forces raids where the legal standards employed to designate targets for lethal action or to review periodic reports of mistakes are entirely secret.4

When he ordered the mission that killed bin Laden, Obama slew a dragon at once dangerous and shrouded by myth. Bissonnette expressed a kind of contempt for bin Laden for not fighting back:

I think in the end, he taught a lot of people to do—you know, martyr themselves and he masterminded the 9/11 attacks. But in the end, he wasn’t even willing to roger up himself with a gun and put up a fight. So I think that speaks for itself.

Operation Neptune Spear succeeded on its own terms but it has exposed how far the grinding machinery of American counterterrorism operations has drifted from the ideals Obama enunciated in his National Archives speech. If Obama is elected to a second term, he will have the political space to reset his kill list policies, to restore to greater primacy missions that seek to capture terrorists and diminish and expose them by putting them on trial for their crimes. Such a change of course would require a fuller measure of political courage than that needed to order the SEALs to Abbottabad.

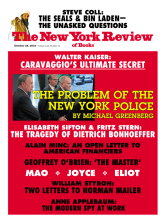

This Issue

October 25, 2012

The Problem of the New York Police

Two Letters to Norman Mailer

-

1

Manhunt: The Ten-Year Search for Bin Laden from 9/11 to Abbottabad (Crown, 2012). ↩

-

2

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012; reviewed in these pages by David Cole, July 12, 2012. ↩

-

3

Gary Schroen, a retired CIA officer who led the first mission to Afghanistan after the September 11 attacks, quotes Black in his memoir, First In: An Insider’s Account of How the CIA Spearheaded the War on Terror in Afghanistan (Presidio, 2005), p. 38. ↩

-

4

See Jo Becker and Scott Shane, “Secret ‘Kill List’ Proves a Test of Obama’s Principles and Will,” The New York Times, May 29, 2012. ↩