On September 3 of this year, an alarming headline ran across six columns of the “World” section of The Times of London: “US Suspends Police Training After Big Rise in Green-on-Blue Attacks.” The dateline was Afghanistan and the peg was that forty-five coalition troops had been killed by Afghan soldiers and police already this year, compared with thirty-five for all of 2011. The number has since risen to fifty-one and joint US–Afghan patrols have been canceled.

I remembered American soldiers in Vietnam wishing that either the Vietcong or Hanoi’s regulars were on their side rather than the Army of the Republic of [South] Vietnam (ARVN). They were notorious for knowing about upcoming ambushes and melting away just before they were sprung, or standing back on sentry duty to allow enemy soldiers to infiltrate American camps where they caused havoc before disappearing into the night. Already in 1954, early in the Eisenhower administration, Walter Robertson, the hard-line assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs, admitted to C.L. Sulzberger of The New York Times, “If only Ho Chi Minh were on our side we could do something about the situation. But unfortunately he is the enemy.”

From the early 1960s, American soldiers in Vietnam knew the truth about the situation in which over 58,000 of them were to die. Apart from a few who deserted or shot themselves badly enough to be invalided home, they had little choice. As Fredrik Logevall’s book Embers of War makes admirably clear, the choices were made by American presidents from Truman to Nixon who knew that Washington had determined, often for domestic American reasons, to back a corrupt and incompetent Vietnamese side, after having paid most of the bills for the French until their collapse in the mid-1950s. By that time, most Vietnamese despised the French.

In 1963, now no longer president, Dwight Eisenhower would write:

I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs, who did not agree that had an election been held as of the time of the fighting, possibly 80 percent of the population would have voted for the Communist Ho Chi Minh as their leader rather than [the French- appointed ex-emperor] Chief of State Bao Dai.

Since it was Eisenhower and his secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, who ensured that no free elections took place in Vietnam, they bear a heavy responsibility for the American deaths, and for the millions of Vietnamese who died in the American–Vietnamese war before it ended.

Fredrik Logevall teaches history at Cornell and his earlier book, Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam,1 showed him to be a considerable authority on Vietnam. Now the eight-hundred-plus pages of his Embers of War provide the most comprehensive account available of the French Vietnamese war, America’s involvement, and the beginning of the US-directed struggle.

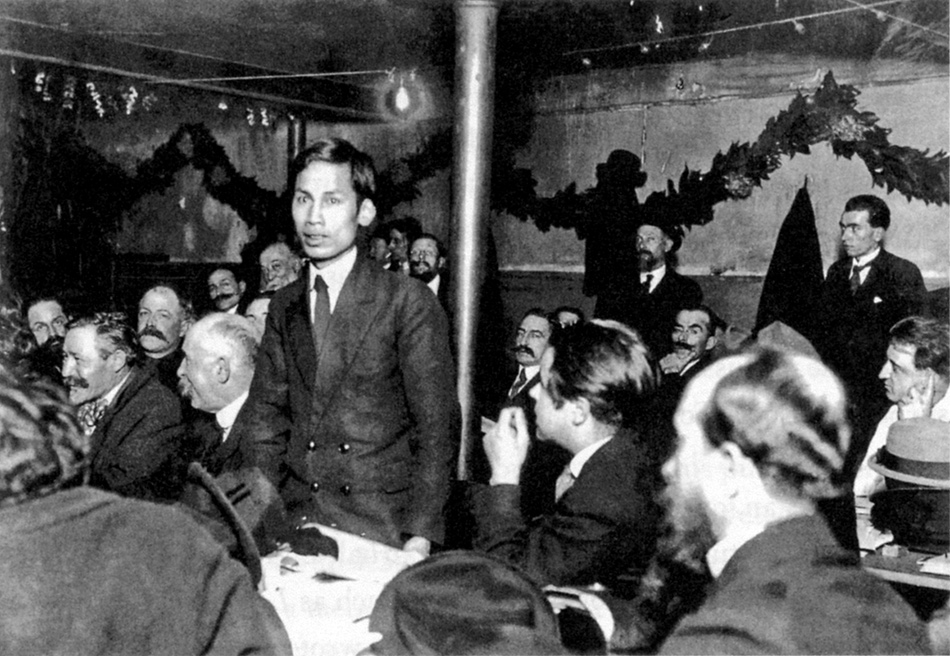

Quite rightly, Logevall begins this long and awful story by tracing the career of Ho Chi Minh, including the poignant photograph of the young Ho in Tours in 1920, appealing to French socialists to support his calls for Vietnamese independence. At Tours a majority of the delegates left the Socialist International to form the French Communist Party. As Sophie Quinn-Judge writes in her uniquely sourced biography of Ho:

Ho’s participation…made him one of the founding members of the French Communist Party….[He] gave his allegiance to a force which would dominate the rest of his life. The world communist movement would become both his family and his chief employer.2

Logevall recounts Ho’s years of hoping that the United States would support the cause of Vietnamese independence, noting his well-known use of the Declaration of Independence in his own speeches and in documents of the Viet Minh, the Communist national coalition he led from its creation in 1941. I doubt, however, that Ho, a master of international manipulation, would ever have abandoned communism. When American OSS teams landed in Communist-controlled areas of Vietnam during World War II, Ho pressed them on “whether Washington would intercede in Indochina or leave matters to the French….” (Carleton Chapman, a doctor with one of the teams and later dean of the Dartmouth Medical School, told me that when he examined Ho he found his tuberculosis to be so grave that he was certain the Viet Minh leader could not survive long.) But Ho also wrote pessimistic letters to an American friend, Charles Fenn, expressing fears that relations with Washington might become “more difficult.”

Ho had every reason for this fear. Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, Logevall writes, “brought to power a new administration, one with a markedly different assessment of what ought to happen in Indochina and in the colonial world generally.” Truman had little knowledge or experience of such matters and after 1949 focused on warding off McCarthy-inspired attacks on those who had “lost China.” Before long the State Department was making clear that it did not object to a full-scale French return to Indochina, as well as tepidly suggesting that Paris might support some local autonomy in its colony. Logevall writes:

Advertisement

In historical terms, it was a monumental decision by Truman, and like so many that US presidents would make in the decades to come, it had little to do with Vietnam herself—it was all about American priorities on the world stage.

By 1947, with the beginnings of the “Truman Doctrine,” Washington conflated the Indochinese conflict with the cold war, seeing it “in the context of the deepening confrontation with the Soviet Union.” This “marked the beginning of an anti-Communist crusade inside the United States” and “a staunch and undifferentiated anti-Communism [that] became the required posture of all aspiring politicians, whether Republican or Democrat.” And yet, as Logevall shows, throughout those years Stalin showed little interest in Ho Chi Minh’s appeals, as was the case to a lesser extent with Mao after 1949.

What Truman knew little about, and his successors ignored even when they suspected it, was

the strong anti-French and nationalist feelings among the vast majority of Vietnamese…. The pervasive anti-French animus enabled Viet Minh forces to assemble undetected, to withdraw when the enemy appeared in force, to hide their weapons, to expand their ranks, and to gather excellent intelligence concerning the strength, the maneuvers, and often even the plans of the French…. Women, children, the elderly, all contributed to the common cause.

The French authority on Indochina Paul Mus wrote in 1945, “In short, what the Vietnamese have preserved, through all the vicissitudes of their history, is a community of blood, of language, of sentiment.” In 1965 I saw a village puppet show in South Vietnam in which, to the delight of the watching peasants, traditionally dressed Vietnamese warriors were knocking about plainly Caucasian puppets. Watching with me was John Paul Vann, a ruthless American of long experience of Vietnam. “That’s us they’re smashing,” he remarked. Such attitudes, as Rory Stewart has shown in these pages,3 are very likely true in Afghanistan today.

Also notable, according to Logevall, was the French intelligence system, which was able to identify with 80 percent accuracy the Viet Minh’s order of battle and predict when major Viet Minh operations would take place. But because this information was never available to units in the field, they were “often victims of the most brutal surprises.” As was true in the American period as well, “it didn’t take French commanders long to realize that many Vietnamese agents had contacts on both sides; one could never be assured of their loyalty.” One of the best-known Vietnamese journalists working in Saigon turned out, after Hanoi’s victory, to be a Viet Minh spy.

Logevall ably surveys decades of scholarship and reporting on the jockeying for advantage at Geneva in 1954, after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu. He contends that near the end of the siege, when a French defeat was certain, the US offered the French nuclear weapons; the French declined largely because such a weapon would have wiped out their own beleaguered garrison. At Geneva, he shows, it was Beijing that persuaded the victorious Viet Minh to agree to a temporary division of Vietnam at the 17th parallel, which was intended to lead to national elections and unification in 1956, an agreement never agreed to by Eisenhower and Dulles, who were to scupper both the temporary nature of the division and the election by ensuring that the government they helped install was not temporary.

In his earlier book Choosing War, an equally solid study, Logevall considered whether at any point during the war, until the Viet Minh had plainly won, there had been “any [serious] interest in negotiations…. At no point during…1964 were American leaders hemmed in on Vietnam…. They always possessed a real choice. Neither domestic nor international considerations compelled them to escalate the war.” This is overdrawn. In both books Logevall is at pains to show that domestic considerations about not looking weak animated each American administration. As I mentioned above, he writes in Embers, “It had little to do with Vietnam itself—it was all about American priorities on the world stage.” This was the reality behind the endless repetitions of the domino theory, that if Vietnam “went,” the rest of Southeast Asia, and possibly beyond, would “go,” too.

Choosing War, substantial and well documented though it is, is less satisfying than Embers of War. It focuses on the years 1963–1965 and so it barely explains how the US got into the situation described in David Halberstam’s The Making of a Quagmire or Daniel Ellsberg’s “The Quagmire Myth and the Stalemate Machine.” In that vital regard Logevall’s Embers of War tells the whole story of the First Vietnam War and the beginning of the second, from the time of Ho Chi Minh’s early years in France.

Advertisement

From the start, as Logevall convincingly shows, the US link to the French was a tangle. He notes the various strands. There was the fear that if France carried the burden in Indochina alone, it could not afford to meet its military and economic obligations in Europe. Washington also feared that Paris might negotiate with the Viet Minh. But there was a concern as well in Washington that Americans must avoid looking like colonialists. In a particularly disgusting—unsourced—document in 1950, it was observed that “much of the stigma of colonialism can be removed if, where necessary, yellow men will be killed by yellow men rather than by white men alone.”

This was the illusion of finding Vietnamese soldiers who would enthusiastically fight the Viet Minh, a proposition leading under US direction to the formation and enlargement of the ARVN. Those were the soldiers so feared by many US troops. That could now be seen by some as similar to raising hopes that someday, in Afghanistan, Afghan soldiers, also increasingly feared as treacherous, will fight the Taliban without Americans at their sides.

Yet Logevall writes that

France’s war was also America’s war—Washington footed much of the bill, supplied most of the weaponry, and pressed Paris leaders to hang tough when their will faltered.

But not too privately, American leaders felt contempt for their French allies. They thought of them, Logevall observes, as cowardly and unimaginative forces, “who had fought badly in Indochina and deserved to lose.” This was an undeserved contempt, he says, because the French Expeditionary Force—made up in great part of troops brought in from other colonies like Morocco and Algeria and Foreign Legionnaires, many of whom were German—“fought with bravery and determination and skill.” This reality was ignored by the Americans, who saw themselves as “the good guys, militarily invincible, who selflessly had come to help the Vietnamese in their hour of need and would then go home”—again, the delusion seen in Afghanistan.

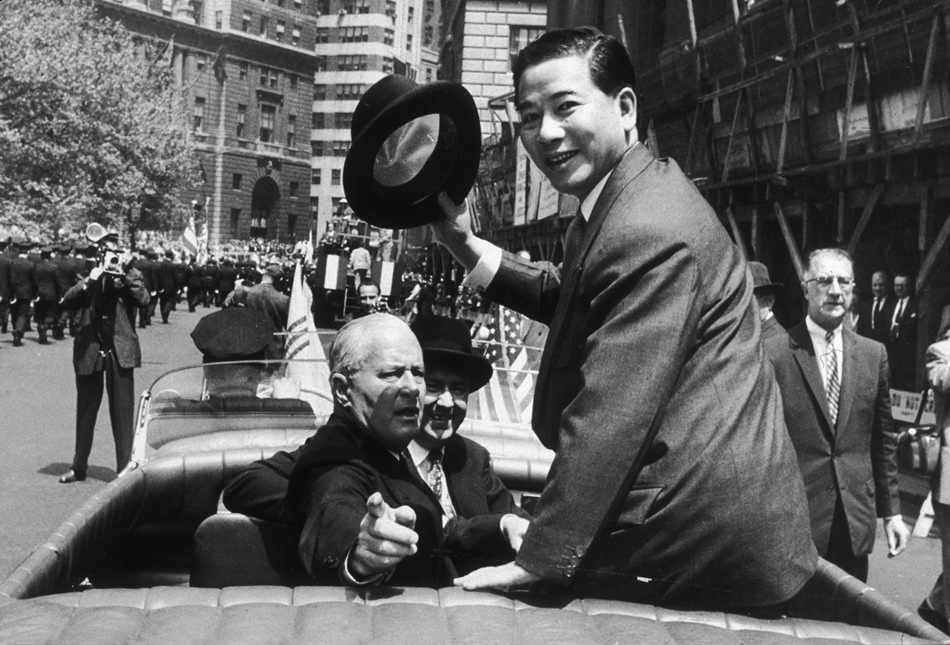

The muddle is further shown in the US agreeing to the French bringing the rigid, suspicious Ngo Dinh Diem onto the scene as president of South Vietnam, and clinging closely to him—despite a brief discussion of deposing him. Diem’s visit to the US in 1957

crystallized the self-congratulatory perception in the popular mind of Ngo Dinh Diem as the lionhearted fighter, the devout Christian in suit and tie, the Miracle Man of Asia, fighting off the rapacious Communists with America’s selfless help.

The New York Times and The Washington Post, years later critics of the war, enthusiastically joined in this praise, although Life magazine, whose publisher Henry Luce was Diem’s greatest American champion, admitted:

Diem and Vietnam still have plenty of problems…. For all its electoral and constitutional show, South Vietnam appears in many ways to be as much of a police state as its Viet Minh rival to the north, and Diem may easily be mistaken for another dictator.

This was a view shared by many of the Saigon journalists. But in 1963, when Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu appeared to be negotiating a settlement with Hanoi, Washington connived in their murder. (The coup against Diem in 1963 is recounted in detail in Choosing War.)

In his epilogue, Logevall sums up with some passion the roots of the disaster that led to and deepened the Second Vietnam War:

Ultimately, Kennedy and Johnson found what their predecessors in the White House as well as a long line of leaders in the French Fourth Republic had found: that in Vietnam, the path of least immediate resistance, especially in domestic political terms, was to stand firm, to maintain the commitment, and to press on, in the hope that somehow things would turn out fine (or at last be bequeathed to a successor). As Democrats, JFK and LBJ felt the need to contend with the ghosts of McCarthy and the charge they were “soft on Communism.” …All Democrats…sought to avoid a repeat of the “Who lost China?” debate, this time over Vietnam.

Older readers will read this book with admiration for Logevall’s copious sources in English, French, and Vietnamese (in translation) and agree with his analysis. They will agree because they learned much about these wars in the 1960s and early 1970s from many of the sources he lists in the bibliographies of both his books. I would not, as Samuel Johnson said of a bulky book, have wished it longer. Logevall includes a number of set pieces, among them one on Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, the best novel about the Americans in Vietnam. Based on Greene’s visits to Vietnam, it is hate-filled and revealing both of the situation and of Greene himself. A few pages, instead of eighteen, would have illustrated Greene’s points and tempted readers to read the book.

The same is true of Logevall’s account of the Viet Minh’s victorious siege of the French bastion at Dien Bien Phu in 1954; this brought the war to very near its end and led to attempts at real negotiations at Geneva and an agreement that the Americans refused to accept. He notes the possible disagreement between Vo Nguyen Giap, the commander of the Viet Minh forces, and his Chinese advisers about whether to order an all-out frontal assault on the French, and he states, too, that Giap, after enormous efforts involving thousands of specially equipped bicycles, sited his artillery—most of the Viet Minh’s heavy weapons had been captured by the Chinese from the Americans in Korea—on the forward slopes of the surrounding hills, enabling the Viet Minh to fire pointblank into the French garrison. Since the story of Dien Bien Phu was well told in the 1960s by Bernard Fall and Jules Roy, as Logevall’s copious footnotes show, here too a shorter account would have left out little, and interested readers could turn to both of their books.

This is not to assert that Logevall obscures or misses the main points; on the contrary, he makes them well but sometimes at too great a length. Somewhat fuller footnotes and a more compact text would have tightened his narrative.

Logevall claims that until Embers of War there was no “full-fledged international account of how the whole saga began.” This depends on what is meant by “full-fledged.” Footnote 8 in his preface lists a large number. Indeed, the footnotes to his first chapters show how much was available two generations ago, and it is those books, articles, newspaper accounts, and speeches that informed the millions in the US and Western Europe who signed huge newspaper appeals, marched, shouted, burned their draft cards, and went to prison. How did those millions learn what animated them except by reading or listening to those who had read and those who had been to Vietnam, like Robert Browne of Fairleigh Dickinson University, who had served as an AID official in Cambodia and Vietnam in the late 1950s and early 1960s and told eager audiences the truth about Washington’s activities? Reading the dispatches from the likes of Homer Bigart, David Halberstam (who changed his mind after initially supporting the war), and Neil Sheehan informed us. So did books and speeches by George McT. Kahin, Bernard Fall, Jean Lacouture, Philippe Devillers, Paul Mus, Frances FitzGerald, Robert Shaplen, and Howard Zinn, and the years of articles by various writers in this journal, stretching back to the 1960s, which earned it the nickname “The New York Review of Vietnam.”

In Choosing War Logevall writes that he was born in 1963, the same year that Presidents Kennedy and Ngo Dinh Diem were murdered,

about as far removed from the scene of the fighting as one could be. I had no memories of the Vietnam War or the controversy surrounding it (even the considerable internal Swedish debate over the struggle in the late 1960s and early 1970s went completely by my young mind).

He describes, too, how as a graduate student in the US he was determined “to fulfill the historians’s obligation to explore what people did—in the context of their own time.” But he says further that it was precisely such an investigation that led him to question “not merely the practicality of the chosen course, but also the morality of it.” Hence his dire prediction that it could happen again.

He somewhat weakens this prediction by criticizing the “‘heroes’…who understood already in 1964 the essential futility of what the United States was trying to do in South Vietnam.” His “flawed” heroes include leaders in allied governments, US senators, some State Department and CIA officers, and “dozens of editorial writers and columnists across the United States.” He criticizes them for not “identifying alternative solutions and the means to achieve them.” This was not the case. Many of those he mentions urged negotiations with the North, when a negotiated outcome validating the participation in government of the Vietnamese Communists was the deepest fear in Washington and its reason for the murder of Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother. But the members of the peace movement wanted the US to leave Vietnam. Many of them were the authorities cited in Logevall’s footnotes. And there were the raucous cries “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh” that offended many Americans unable to make up their minds. But these shouts were only less respectable versions of the admissions of President Eisenhower and his assistant secretary of state Walter Robertson that Ho Chi Minh could have been a powerful ally.

Shouting “out” may seem naive, trusting, or even dishonest, especially when we reflect on what happened in Vietnam after the Viet Minh took over. The Vietcong—the National Liberation Front—with its own history and deep southern roots had been shuffled off the scene even at the victory parade after Saigon fell. The monks who had played such an important part in shaking the legitimacy of the Thieu-Ky regime were detained, and a harsh system of camps imprisoned those deemed to be enemies of the new unified Vietnam. The Hanoi regime is repressive, concerned with its own control and advantage. In 1990 I wrote in these pages:

Many of the [North] Vietnamese to whom visitors manage to talk in private also feel they have been cheated out of victory, although they were the victors; and more deeply, as [Morley] Safer shows, many feel a recurrent grievance at having been cheated out of the decent society they hoped for. Their country is poor and oppressive, and hundreds of thousands of people, some of them interviewed by Larry Engelmann and James Freeman in their books on the Vietnamese, have risked drowning, piracy, and rape to flee abroad.4

In 2010, Mai Elliott, an expert on Vietnam, wrote to me, “The war veterans feel that they have made horrendous sacrifices only to see themselves marginalized and to see the Party and military elite enrich themselves.” Broad dissatisfaction was obvious in Hong Kong; increasing numbers of Vietnamese “boat people” risked a long and dangerous ocean trip to reach a measure of freedom there, even in the British detention camps, from which many were—shamefully—flown back to Vietnam.

In Embers of War Logevall writes:

My goal in this book is to help a new generation of readers relive this extraordinary story: a twentieth-century epic featuring life-and-death decisions made under profound pressure…and a remarkable cast of larger-than-life characters….

This reduces a vast disaster for the Vietnamese people and a gigantic crime by generations of senior officials in France and Washington to promotional lingo.

But Logevall is far more profound than that. Readers who remember the debates during the Vietnam War, he rightly says, will experience déjà vu when reading his new book:

The soldierly complaints about the difficulty of telling friend from foe, and about the poor fighting spirit among “our” as compared to “their” indigenous troops…; the solemn warnings against disengagement…all these refrains, ubiquitous in 1966 and 1967 (and in 2004 and 2005), could be heard also in 1948 and 1949.

In 1965 Charles de Gaulle, who had had a leading part in reclaiming French control of Indochina after World War II, predicted, wholly accurately, that “unless the Johnson administration moved to halt the war immediately, the struggle would go on for ten years and completely dishonor the United States.” In April 1991, when challenged about his role in the war, ex–Defense Secretary Robert McNamara admitted, “I was wrong! My God, I was wrong.”5

In 1999, in the final paragraph of Choosing War, Logevall said with acute prescience, “And there is this, finally, to say about America’s avoidable debacle in Vietnam: something very much like it could happen again.” His two books, especially Embers of War, tell the deeply immoral story of the Vietnam wars convincingly and more fully than any others. Since many of the others, some written over fifty years ago, are excellent, this is a considerable achievement.

-

1

University of California Press, 1999; see my review in these pages, May 25, 2000. ↩

-

2

Ho Chi Minh: The Missing Years, 1919–1941 (University of California Press, 2003), pp. 31, 33. ↩

-

3

“Afghanistan: What Could Work,” The New York Review, January 14, 2010. ↩

-

4

“The War That Will Not End,” The New York Review, August 16, 1990. ↩

-

5

Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History (Viking, 1983; Penguin, 1991), p. 24. Earlier editions do not have this quote. ↩