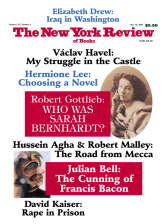

Sarah Bernhardt won’t go away. She was born in 1844 and died in 1923, long past her glory days and well out of our reach. Her few silent films are awkward and off-putting. Yet she remains the most famous actress the world has ever known. Books about her, films, plays, dance works, documentaries, exhibitions, merchandise—they keep on coming. Only last year, a big new biography was published in France—respectable, but essentially going over the same old ground. Also last year, the Jewish Museum in New York staged an exemplary Bernhardt exhibition, which demonstrated, among other things, why Bernhardt was the priestess of Art Nouveau, with her elaborately rich costumes, her splendid ornaments of gem-studded precious metals, and—obvious in the portraits, the photographs, the caricatures—the way she almost always stood and sat: in a pure Art Nouveau spiral.

Among the scores of books on Bernhardt, there have been two major biographies in English: by Ruth Brandon (1991), particularly perceptive on Sarah’s emotional life, and by Robert Fizdale and Arthur Gold (also 1991), brilliant on her artistic and social surround. And let’s at least acknowledge Françoise Sagan’s bizarre contribution, Dear Sarah Bernhardt (1988), a fictional exchange of letters between Sagan and the long-gone Sarah. (It turns out they had a lot to say to each other.)

Other fiction? At least a dozen novels, beginning in the nineteenth century with Edmond de Goncourt’s mean-spirited La Faustin, Félicien Champsaur’s Dinah Samuel (Sarah as lesbian), and the sensational roman à clef The Memoirs of Sarah Barnum by her one-time intimate Marie Colombier. And, as recently as 2004, Adam Braver’s Divine Sarah, a confused fantasy of Bernhardt doing drugs in L.A.

The movie The Incredible Sarah starring Glenda Jackson? Flee it. The French TV documentary with English voice-over by Susan Sontag? Not very illuminating. Jacqulyn Buglisi’s modern-dance work Against All Odds (I saw it only a few weeks ago in New York)? Unconvincing. On the other hand, totally unlikely and highly amusing: her star turn in one of the “Lucky Luke” books (like Tintin and Astérix, a hugely successful French series of graphic novels for kids). Sarah is setting out on the Wild West leg of her first American tour and President Rutherford B. Hayes entrusts her safety to Cowboy Luke.

And then there’s her presence in a variety of Hollywood movies, from Marilyn Monroe in The Seven Year Itch (“Every time I show my teeth on television, I’m appearing before more people than Sarah Bernhardt appeared before in her whole career”) to Judy Garland in Babes on Broadway to an aging Ginger Rogers as a very young Sarah, intoning “La Marseillaise” in The Barkleys of Broadway.

Merchandise? In the past few months eBay has brought me the 1986 “Dame aux Camélias” memorial plate (Limoges); one of several available embroidery patterns based on the famous Art Nouveau posters by Mucha; and a 1973 Mexican comic book called Sara, la Artista Dramática Más Famosa en la Historia del Teatro. So far I’ve resisted the book of Sarah Bernhardt paper dolls, the Madame Alexander Sarah Bernhardt doll, the “asymmetrical” Bernhardt earrings, and the “Heirloom” Sarah Bernhardt peony.

Why this ongoing attention to a French theatrical star of the distant past? You can ascribe it to Sarah’s rich and notorious private life, always ripe for retelling; to the central role she played in the history of the theater in particular and the culture of her time in general; to the unique way she grew into legend—morphing from a tarty little actress into the most famous French person of her century after Napoleon and the most admired Frenchwoman in history after Joan of Arc (whom she played—twice; she didn’t manage Napoleon, but one of her greatest triumphs was as his doomed son, L’Aiglon).

Her undying celebrity would not have surprised her: from her earliest years she was determined to be noticed, to conquer the world, and to do it her own way. When at the age of nine she was dared to jump a ditch and broke her wrist falling into it, she cried out in rage, “Yes, yes, and I’ll try it again if I’m dared to! I’m going to do exactly what I want all my life!” That’s when she decided on “Quand même” as her motto, and she never relinquished it. She decorated her stationery, her dishes, her silver with it; it was inscribed on the flag she flew over the little fort she bought and summered in on Belle-Isle, off the Brittany coast; it was as much a part of her legend as her scrawniness, her legion of lovers, the coffin she sometimes liked to sleep in. But how to translate it? “Even so”? “No matter what”? “All the same”? “Despite everything”? “Nevertheless”? “Against all odds”? “Whatever”?

Advertisement

“Quand même” may not be translatable, but the message is clear: “Nothing can stop me!” And nothing did—not war, illness, scandal, bankruptcy. Sarah was not only “divine,” she was indefatigable, reckless, tireless, brave, commanding. She has to reach New Orleans for a performance while floods are threatening a bridge over a swollen river? She bribes the engineer of her private train to make the desperate attempt, and moments after they’re safely across, they hear the bridge crash into the river. When she’s a seventeen-year-old debutante at the Comédie-Française, she explodes when a veteran actress slaps her little sister backstage and slaps her back, refuses to apologize, and is gone from the company. Marie Colombier publishes that scandalous roman à clef? With her son, Maurice, and her current lover, she invades Marie’s apartment, wreaks havoc, and slashes her with a whip. Quand même.

She was provocative, generous, maddening, fun to be with—and untruthful: self-dramatizing, embroidering, storytelling. That bridge on the way to New Orleans? Maybe, although in three different accounts—her own, her granddaughter’s, her grandson-in-law’s—it’s a different river and a different destination each time. Basic facts? We can’t be certain what year she was born, what street she was born on, or even who her father was—a young law student named Édouard Bernhardt (or was he her mother’s brother)? A naval officer from Le Havre named Morel? Paris’s Hôtel de Ville, where the relevant municipal data were kept, went up in flames during the Commune. It’s not even 100 percent certain that the father of her beloved Maurice (she was twenty when he was born) was the Belgian Prince de Ligne. Her story is that the Prince wanted to marry her, but his stuffy aristocratic family said “Non“—shades of La Dame aux Camélias; Marie Colombier’s far more likely story is that when Sarah invaded the Prince’s mansion in Paris with the news of her pregnancy, he showed her to the door, remarking that when you sit on a patch of thorns, you can’t tell which particular thorn has scratched you.

And is it remotely possible that on her first Atlantic crossing, in 1880, she saved the life of Abraham Lincoln’s widow by grabbing her when a huge wave struck the ship and Mrs. L. was about to plunge headfirst down a dangerous staircase? “A thrill of anguish ran through me,” writes Sarah in her autobiography, My Double Life,

for I had just done this unhappy woman the only service I ought not to have done her—I had saved her from death. Her husband had been assassinated by an actor, Booth, and it was an actress who had now prevented her from joining her beloved husband. I went back to my cabin and stayed there two days….

We can turn to Dumas fils, author of La Dame aux Camélias (she played it almost three thousand times), for the ultimate word on Sarah’s veracity. Referring to her notorious thinness—the physical quality that most defined her, that was endlessly derided and caricatured in her early years—he said affectionately, “You know, she’s such a liar, she may even be fat!”

In regard to her childhood we have only her memoirs to go by, and though they’re factually preposterous, they come across as emotionally true. Yes, her demi-mondaine mother, known as Youle, sent her off semi-permanently to a farm in Brittany (her first language was Breton), but did she really fall into a fire only to be saved by some neighbors who threw her “all smoking, into a pail of milk”? When eventually she was brought to Paris by her nurse-turned-concierge, was she really lost to her mother, like a child in Dickens or Les Misérables, and only retrieved when her Aunt Rosine happened to alight from her carriage in the sordid courtyard where tiny Sarah was playing? And did she then really fling herself from a window, breaking her arm and her kneecap, to prevent Rosine from leaving without her?

Yet however fanciful her autobiography is, it has verve and charm—what Max Beerbohm called its “peculiar fire and salt…[its] rushing spontaneity.” She’s completely believable in the portrait she sketches of herself as a child installed at a fashionable convent school: turbulent, savage, imperious. (Those poor nuns!) And we sense all too keenly her anguish at having been abandoned by her adored mother: adored, but not adoring. From the first, Youle dealt with her as an impediment, not a beloved child. The favorite was Sarah’s half-sister Jeanne (father unknown), who was placid, conventionally pretty (Sarah never looked like anyone else), and easy to control. Not even the strict and withholding Youle, who was even coldly dismissive of her acting, could control Sarah—nobody ever could.

Advertisement

The depth of the psychic wounds she received as a sensitive child with no father and a rejecting mother reveals itself not only in the elaborations of her memoirs but in The I dol of Paris, a trashy semi-autobiographical novel she produced late in life. Her heroine, Espérance, is not only a beautiful budding actress of genius but has ideal parents: a distinguished professor of philosophy about to be inducted into the Académie Française and a loving, tender mother—they live and breathe to attend to her every whim. As a novel it’s ludicrous, but as an act of wish-fulfillment it’s fascinating—and saddening. Clearly, despite the unparalleled triumph of her life, she never got over having been an unwanted and unloved child.

When she was twelve, Sarah took her first communion and officially became a Catholic, despite the fact that her mother was Jewish, of German-Dutch stock. In the convent she also learned the manners and speech of well-bred Parisians—she could pass for a lady. But she wasn’t a lady, so what was she to do with her life? The turning point came when she was fifteen—out of the convent, fit for no occupation, and a drag on her mother’s life and finances. The illegitimate daughter of a courtesan, Sarah could hardly marry into society, and she was adamant about not marrying into the dreary petit-bourgeois world some of her relatives would have settled for.

Youle and Rosine were comfortably established in their demi-mondaine world, making the rounds of Europe’s fashionable spas with their wealthy “protectors,” entertaining many of the great figures of the Second Empire—Rossini, Dumas père, the Emperor Louis-Napoléon’s doctor, and, most important by far, the Duc de Morny, one of Rosine’s lovers (and maybe one of Youle’s as well) and the most powerful man in France other than his half-brother, the Emperor himself.

Something had to be done about Sarah, and a family conference was held to decide her fate. Among those present were her godfather, her upstairs neighbor the angelic Madame Guérard, who was to become her greatest friend and protectress, and—in attendance on Rosine—Morny who, after endless discussion, casually remarked, “Take my advice. Send her to the Conservatoire.” It was settled, and Sarah—who claims she had never been to a theater and had notions of becoming a nun—was soon feverishly preparing to audition.

The outcome was never really in doubt, given Morny’s influence. Even so, the audition had to proceed according to the rules. When Sarah’s turn came, she was asked who was going to cue her, but no one had informed her of this requirement. “Then I’ll recite La Fontaine’s Les Deux Pigeons.” Recite rather than perform a scene? Uproar! She triumphed, however, her voice so ravishing, her diction so exquisite that, against custom, she was accepted on the spot. Her life was ready to begin.

But unlike her alter ego Espérance, Sarah had a hard road to travel before she prevailed. She did well though not brilliantly at her studies. Her short first stay at the Comédie-Française was less than distinguished, although she was certainly noticed, if only for that notorious thinness and the uncontrollable red-blonde hair. The first review she received from the all-powerful critic Francisque Sarcey, on the occasion of her debut as Racine’s Iphigénie, was hardly auspicious:

Mlle. Bernhardt…is a tall, attractive young woman with a slender waist and a most pleasing face…. She carries herself well and pronounces her words with perfect clarity. That is all that can be said for the moment.

Some days later, on the occasion of her appearance in Les Femmes Savantes, he had more to say: “That Mlle. Bernhardt is inadequate is unimportant…. It is natural that there are some beginners who do not succeed.”

She was gone from the Comédie-Française in a matter of months, and for three years there was no work apart from a few scattered and frivolous engagements. How did she live? She was on her own, with her baby, Maurice, and Madame Guérard—and a circle of affluent and influential men whom she “entertained” and who contributed to her expenses, even clubbing together to buy her the famous coffin she was so eager to acquire.

It was only in 1866 that she found herself back in the theatrical mainstream, offered a place at the Odéon, France’s second official theater. An affair with its young administrator, some early reversals, the growing band of vociferous Left Bank students who made her their favorite, and then success in Dumas père’s Kean, bigger success in François Coppée’s Le Passant (her first trouser role), and finally, in 1872, the first immense success of her career, in a revival of Victor Hugo’s Ruy Blas.

The critics, led by Sarcey, were ecstatic over her nobility and beauty, the perfection of her poetry. Ruy Blas had two immediate consequences. First, a secret fling with Hugo, a mere forty-two years her senior (for a moment it even looked as if there might be a baby). And, of more consequence, the capitulation of the Comédie-Française. There was no way that France’s most important theater could ignore France’s most acclaimed young actress. Her contract with the Odéon? She broke it, paying a large fine. Ten years after her ignominious departure from the Comédie, Sarah was back. As the critic Théodore de Banville put it, “Poetry has entered the domain of dramatic art. Or, if you like, the wolf has entered the sheepfold.”

She stayed for just under eight years. At last, at the advanced age of thirty, she played Phèdre, confirming her position as the greatest tragedienne since Rachel. She was now the theater’s biggest attraction—by the time the company was negotiating a season in London, the English impresarios refused to proceed unless she was part of the deal. And in London she carried everything before her. “It would require some ingenuity,” wrote Henry James,

to give an idea of the intensity, the ecstasy, the insanity as some people would say, of curiosity and enthusiasm provoked by Mlle. Bernhardt…. I strongly suspect that she will find a triumphant career in the Western world. She is too American not to succeed in America. The people who have brought to the highest development the arts and graces of publicity will recognize a kindred spirit in a figure so admirably adapted for conspicuity.

(James was to use her as his model for Miriam Rooth, the heroine of The Tragic Muse, just as Proust would use her as his model for Berma.)

James was prophetic. Returning to Paris, Sarah found excuses for being offended by the Comédie’s management, breaking yet another contract and instantly forming her own company for a whirlwind tour of the Continent before setting out for America. The die was cast. From 1880 until her death, she remained in sole control of her career. She chose her plays, her co-actors, her managers. She ran her own theaters. She oversaw the lighting, she commissioned the scenery and costumes, often she directed. And, perhaps not surprisingly, when she took command of her life, her previously fragile health miraculously righted itself. Only her agonizing stage fright—le trac—stayed with her to the end.

This American tour, the first of nine, lasted six months (short by her future standards; one world tour lasted two and a half years), and America rewarded her with money and fame. Wherever she appeared there was sensation (much of it about her exotic menagerie, which at various times included a lynx, a lion, a baby alligator that died from being fed too much champagne, and a boa constrictor which killed itself by swallowing a sofa cushion). And of course there was gossip (much of puritanical America was scandalized by her unconventional, and highly public, love life, to say nothing of her illegitimate child). In countless magazines and newspapers everything about her was both breathlessly reported and gleefully parodied. A typical verse, from Puck:

Sadie!

Woman of vigorous aspirations and remarkable thinness!

I hail you. I, Walt Whitman, son of thunder, child of the ages, I hail you.

I am the boss poet, and I recognize in you an element of bossness that approximates you to me….

The Worcester Evening Gazette condensed La Dame aux Camélias for its busy readers:

ACT I—PARIS

He—You are sick. I love you.

She—Don’t. You can’t afford it.

ACT II—PARIS

She—I think I love you. But good-bye; the Count is coming.

He—That man? Then I see you no more. But no! An idea! Let us fly to the country.

ACT III—THE COUNTRY

His Father—You ruin my son! Leave him.

She—He loves me.

His Father—You are a good woman. I respect you. Leave him.

She—I go.

ACT IV—PARIS

She—You again? I never loved you.

He—Fly with me, or I die.

She—I love you; but good-bye now.

ACT V—PARIS

She—(Very sick.) Is it you? Is God so good?

He—Pardon me. My father sent me.

She—I pardon you. I love you. I die. [Dies. Tears. Sensation. Curtain.]

But the critics and the audience weren’t only condemning or laughing; they also found in her acting—and celebrated—a realism, an emotional truth that was absent from the more extravagant melodramatic style of the American theater at that time.

The most telling change in Sarah’s career during this period was her new repertory. At the Comédie-Française she was mostly interpreting the classics. Now she was appearing almost exclusively in what was known as boulevard drama: Adrienne Lecouvreur, Frou-Frou, La Dame aux Camélias. And then, in 1882, came the first of the blood-and-thunder vehicles Victorien Sardou concocted for her: Fédora (Russian nihilists), to be followed by Théodora (Byzantine empress), La Tosca, Cléopâtre, Gismonda, La Sorcière, in almost all of which roles she perished in the final scene. In fact, her deaths—by poison, by strangulation, by disease, by suicide—were perhaps her strongest suit: drawn out, accurately differentiated, grippingly realistic. And since the subtleties of her diction could mean little to the foreign audiences before whom she now mostly performed, she depended more and more on glamorous costumes and scenery and personal adornment; on her genius for striking gestures and poses (no wonder Edmond Rostand famously acclaimed her “Reine de l’attitude et Princesse des gestes“); on her projected sexuality; and of course on the famous voice—la voix d’or, as Hugo dubbed it—which appears in reality to have been more silvery than golden. (Rachel’s had been a voice of bronze.)

Throughout her early career, it was indeed Rachel—also Jewish, and with a comparably conspicuous private life—to whom she was constantly compared, especially in regard to their highly different approaches to Phèdre. The critic for the Times of London clarified that difference: while Rachel’s Phèdre inspired awe, Sarah’s inspired sympathy; her Phèdre was a tormented woman in the throes of passion rather than a statuesque emblem of antique tragedy. As for Rachel’s favorite Corneille, he was not for Sarah. His noble heroines were too invested in la gloire, not enough in l’amour.

During the latter part of Sarah’s career, it was Eleanora Duse to whom she was constantly compared, but now, ironically, it was Sarah who was considered artificial, Duse the apostle of the natural. Their repertories overlapped to a certain degree, but Sarah kept away from Duse’s Ibsen, Duse from Sarah’s classic heroines. The critic Desmond McCarthy put it this way: “The art of Sarah Bernhardt made us first conscious of the beauty of emotions and passions, while that of Duse was a revelation of the beauty of human character.” When the rival divas’ paths crossed, they were scrupulously polite; in private, equally bitchy. But essentially Duse was an irrelevancy to Sarah. As Maurice Baring explained, “She took herself for granted as being the greatest actress in the world, as Queen Victoria took for granted that she was Queen of England.”

Duse, certainly, never attempted the trouser roles that Bernhardt so enjoyed. (“I don’t prefer men’s roles,” she said; “I prefer men’s minds.”) Among her men: Musset’s Lorenzaccio, Rostand’s L’Aiglon (L’Aiglon was twenty, Sarah fifty-six), Pelléas, Werther, Judas, and of course Hamlet. Far from being the Romantic era’s indecisive weakling, her Prince of Denmark was virile and determined (not unlike Madame herself). Some critics were impressed. Not Max Beerbohm, who ended his review by saying, “Yes! the only compliment one can consciously pay her is that her Hamlet was, from first to last, très grande dame.”

Her progress, if that’s what it was, from the classicism of the Comédie-Française to the melodrama of Sardou (or, as Shaw called it, Sardoodledom) can be likened to the more or less contemporaneous “progress” in operatic style from bel canto to verismo. Lytton Strachey explained her artistic choices wryly yet sympathetically:

This extraordinary genius was really to be seen at her most characteristic in plays of inferior quality. They gave her what she wanted. She did not want—she did not understand—great drama; what she did want were opportunities for acting; and this was the combination which the Toscas, the Camélias, and the rest of them, so happily provided. In them the whole of her enormous virtuosity in the representation of passion had full play; she could contrive thrill after thrill, she could seize and tear the nerves of her audiences, she could touch, she could terrify, to the very top of her astonishing bent. In them, above all, she could ply her personality to the utmost.

As for her private life—not that it was ever very private—as a matter of course she slept with almost all her leading men, most clamorously with her male vis-à-vis at the Comédie-Française, Jean Mounet-Sully—a lion of a man. (In his old age he was to remark, “Up to the age of sixty I thought it was a bone.”) He was determined to marry her, she would have none of it, and their incendiary relationship crashed and burned. The most notorious of her leading men, whom she had turned into an actor, was the man she shocked her world by marrying—Aristides Damala, a handsome, aristocratic Greek who proved to be a disaster both as actor and husband. Congenitally unfaithful, envious of her fame, dishonest financially, he was to die young of morphine addiction. Sarah mourned him, for years referring to herself as the Widow Damala.

Even so, she turned at once to new lovers, having already “entertained” such eminences as Edward, Prince of Wales; Gustave Doré (who helped her with her not inconsiderable career as a sculptor); d’Annunzio (a slap at Duse); Pierre Loti; the elegant Charles Haas, on whom Proust modeled Swann; and the ultra-homosexual Robert de Montesquieu, Proust’s Charlus, whom she mischievously initiated into heterosexual sex, reducing him to twenty-four hours of vomiting. There had been scores—hundreds?—of others, presumably the last of whom was the beautiful young Lou Tellegen, a gift to her from her close colleague the very homosexual Édouard de Max. Questioned about Tellegen (she was sixty-six), she replied, “To my last breath I will live as I have lived.” Tellegen wrote lovingly—and discreetly—about their relationship in his autobiography, Women Have Been Kind.

Despite all this activity, however, for most of her life she apparently couldn’t achieve orgasm. (Marie Colombier called her “an untuned piano, an Achilles vulnerable everywhere except in the right place.” Another witticism given wide currency: “She doesn’t have a clitoris, she has a corn.”) Unquestionably the most important man in her life, the one she loved passionately from start to finish, was not a lover but her son, Maurice, whom she raised to be an aristocrat, a blade, and whom she spoiled, cosseted, and adored.

Her friends and acquaintances? Everyone. In America she drops in on Edison, beards Longfellow in his home. (“Can you read my poetry?” “Yes. I read your ‘He-a-vatere.'” “My—Oh yes—’Hiawatha.’ But you surely do not understand that?” “Yes, yes, indeed I do. Chaque mot.”) In England she’s on the best of terms with Ellen Terry, Henry Irving, and Mrs. Patrick Campbell, to whose Mélisande she played Pelléas (in French), as well as with Queen Alexandra and, later, Queen Mary. Oscar Wilde writes Salome for her—the censors squelched it. As she proceeds on her ceaseless world tours she’s feted by kings, tsars, emperors. When she sinks to the floor in the deepest of curtsies before Tsar Alexander III, he protests, “No, no, it is We who must bow to you.”

Her admirers? To name a few: Mark Twain (“There are five kinds of actresses: bad actresses, fair actresses, good actresses, great actresses—and then there is Sarah Bernhardt”); Freud (“After the first words of her lovely, vibrant voice I felt I had known her for years”); D.H. Lawrence (“She represents the primeval passion of woman, and she is fascinating to an extraordinary degree”).

Her detractors? Chekhov, Turgenev, and most famously George Bernard Shaw, who derided what her acting had become by the time he was reviewing, in the 1890s—“a worn out hack tragedienne”—although he later confessed, “I could never as a dramatic critic be fair to Sarah B., because she was exactly like my Aunt Georgina.”

The route she traversed from scandal to national heroine—the symbol of La France—is a complicated one. In 1870, during the siege of Paris, the theaters are shut down, and she turns the Odéon into a hospital for wounded soldiers, nursing the men indefatigably (and knowledgeably). She’s a violent Dreyfusard, rallying to support Zola, for the only time in her life breaking with Maurice. She violently opposes capital punishment—“I hate the death penalty! It’s a vestige of cowardly barbarism”—although she attends four executions, no doubt to take notes on how people die. When begged by the German ambassador to Belgium to perform in Germany—she can name her price!—the sum she names is five billion francs, the exact sum Germany extracted from France as war reparations.

In a word, she loves and identifies with France. Yet she always boasts of “my beloved blood of Israel,” even though for years her Jewishness—and what was seen as her natural Jewish tendency to money-grubbing—are the objects of ugly caricature and slander. And France comes to love her. “France has only one ambassador—Sarah Bernhardt!” says the French ambassador to Russia at a formal dinner. When she dies, her funeral cortege is followed by hundreds of thousands of people.

Her bravery never faltered. In 1915, after years of agonizing pain in her knee, she decides to have her leg amputated. (She’s seventy.) Firing off telegrams to her friends—“Tomorrow they’re taking my leg off. Think of me, and book me some lectures for April”—she not only survives the operation, she refuses a prosthetic device (the legend of her stomping around the stage on a wooden leg is pure fable) and arranges to have herself carried everywhere in a made-to-order sedan chair. This is how she manages her final American tour—to ninety-nine towns. And this is how in 1917 she’s transported to the front, in easy hearing distance of the guns, so that she can recite patriotic poetry to the troops.

To the end she goes on working. She’s rehearsing a play by Sacha Guitry when she collapses from the uremia that has tormented her for years. Carried to her house, which she never leaves again, she persists with the last of her movies—they come to film her at home. Then coma, and death—in Maurice’s arms.

One of the last people to interview her was Alexander Woollcott, two months before she died. She’s thinking of another American tour, she tells him, but this time not a long one, since she’s “much too old for such cross-country junketing…. Of course, I shall play Boston and New York and Philadelphia and Baltimore and Washington. And perhaps Buffalo and Cleveland and Detroit and Kansas City and St. Louis and Denver and San Francisco….”

Of course. How could she stop? Like Pavlova, like Nureyev, she was a driven performer, endlessly working at her art, eternally touring. “I love, I adore my profession,” she said.

I serve it constantly. I never stop acting. I’ve always acted—always and everywhere, in all sorts of places, at every instant—always, always. I am my own double. I act in restaurants when I ask for more bread. I act when I ask Julia Bartet’s husband how his wife is feeling. Blessed work that fills me with drunken joy and peace, how much I owe to you!

This Issue

May 10, 2007

-

Additional books on Sarah Bernhardt drawn on for this article:

Madame Sarah

by May Agate

Home and Van Thal, 223 pp. (1945) Sarah Bernhardt

by Sir George Arthur

London: Heinemann, 178 pp. (1923) Sarah Bernhardt: A French Actress on the English Stage

by Elaine Aston

Berg, 173 pp. (1989) Sarah Bernhardt: La Premiëre Star du Thètre Face aux Photographes

by Michële Auer

Neuchå?tel: Photogalerie, 255 pp. (2000) Sarah Bernhardt

by Maurice Baring

Benjamin Blom, 162 pp. (1933; reissued 1969) Around Theatres

by Max Beerbohm

Knopf, 2 volumes, 749 pp. (1930) Sarah Bernhardt: My Grandmother

by Lysiane Bernhardt,

translated from the French by Vyvyan Holland

Hurst and Blackett, 232 pp. (1949) The Art of the Theatre

by Sarah Bernhardt,

translated from the French by H. J. Stenning,

with a preface by James Agate

Benjamin Blom, 224 pp. (1924) Memories of My Life

by Sarah Bernhardt

Benjamin Blom, 456 pp. (1908; reissued 1968) The Real Sarah Bernhardt

by Mme. Pierre Berton,

translated from the French by Basil Woon

Boni and Liveright, 361 pp. (1924) Divine Sarah

by Adam Braver

William Morrow, 256 pp. (2004) Tragic Muse: Rachel of the Comèdie-Franáaise

by Rachel M. Brownstein

Knopf, 318 pp. (1993) Sarah Bernhardt

by Andrè Castelot

Paris: Le Livre Contemporain, 249 pp. (1961) Dinah Samuel

by Fèlicien Champsaur,

with an introduction by Jean de Palacio

Paris: Sèguier, 573 pp. (1999) Portraits-Souvenir

by Jean Cocteau

Paris: Grasset, 249 pp. (1935) Dieux des Planches

by Bèatrix Dussane

Paris: Flammarion, 224 pp. (1964) Sarah Bernhardt

by William Emboden,

with an introduction by Sir John Gielgud

Macmillan, 176 pp. (1975) Such Sweet Compulsion

by Geraldine Ferrar

Greystone, 303 pp. (1938) Come to the Dazzle: Sarah Bernhardt's Australian Tour

by Corille Fraser

Sydney: Currency, 358 pp. (1998) Sarah Bernhardt

by G. G. Geller,

translated from the French by E. S. G. Potter

London: Duckworth, 272 pp. (1933) Le Faustin

by Edmond de Goncourt,

translated from the French by G. P. Monkshood and Ernest Tristan

H. Fertig, 250 pp. (1976) Portraits de Sarah Bernhardt

edited by Noîlle Guibert

Paris: Bibliothëque Nationale de France, 207 pp. (2000) Sarah Bernhardt: Impressions

by Reynaldo Hahn,

translated and with an introduction by Ethel Thompson

London: Elkin Mathews and Marrot, 114 pp. (1932) After the Lions

by Ronald Harwood

Amber Lane, 64 pp. (1983) Our Lady of the Snows: Sarah Bernhardt in Canada

by Ramon Hathorn

Peter Lang, 327 pp. (1996) Sarah Bernhardt

by Jules Huret,

translated from the French by G. A. Raper and with a preface by Edmond Rostand

Lippincott, 192 pp. (1899) The Memoirs of Sarah Bernhardt: Early Childhood Through the First American Tour and Her Novella, In the Clouds

edited and with an introduction by Sandy Lesberg

Peebles, 256 pp. (1977) Sarah Bernhardt: LíArt et la Vie

by Jacques Lorcey,

with a preface by Alain Feydeau

Paris: Sèguier, 159 pp. (2005) Drama

by Desmond MacCarthy

Putnam, 376 pp. (1940) Melodies and Memories

by Nellie Melba

London: Butterworth, 335 pp. (1925) Sarah Bernhardt in the Theatre of Films and Sound Recordings

by David W. Menefee,

with a foreword by Kevin Brownlow

McFarland, 160 pp. (2003) Souvenirs de ma Vie

by Marguerite Moreno,

with a preface by Colette

Paris: Phèbus, 328 pp. (2002) Lucky Luke: Sarah Bernhardt

drawings by Morris,

with text by X. Fauche and J. Lèturgie

Paris: Dargaud, 46 pp. (1982) Sara, la Artista Dramtica Ms Famosa en la Historia del Teatro

comic book in the Mujeres Cèlebres series

Mexico: Organizaciûn Editorial Novaro, 32 pp. (1973) La Divine: Le Roman de Sarah Bernhardt

by Michel Peyramaure

Paris: Laffont, 475 pp. (2002) Fils de Rèjane: Souvenirs, 1895-1920

by Jacques Porel

Paris: Plon, 377 pp. (1951) Fils de Rèjane: Souvenirs, 1920-1950

by Jacques Porel

Paris: Plon, 303 pp. (1952) My Blue Notebooks

by Liane de Pougy,

translated from the French by Diana Athill,

with a preface by R. P. Rzewuski

Harper and Row, 288 pp. (1979) Sarah Bernhardt: Une Vie au Thètre

by Ernest Pronier

Geneva: Editions Alex Jullien, 414 pp. (1941) Henry James: Essays on Art and Drama

edited by Peter Rawlings

Scolar/Ashgate, 537 pp. (1996) Journal, 1887-1910

by Jules Renard,

edited by Lèon Guichard and Gilbert Sigaux

Paris: Bibliothëque de la Plèiade, 1,426 pp. (1965) Sarah Bernhardt: Artist and Woman

by A. L. Renner

A. Blanck, 101 pp. (1896) Sarah Bernhardt

by Joanna Richardson

London: Max Reinhardt, 207 pp. (1959) Time Was

by W. Graham Robertson,

with a foreword by Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson

London: Hamish Hamilton, 344 pp. (1931) Sarah Bernhardt

by Maurice Rostand

Paris: Calmann-Lëvy, 123 pp. (1953) I Knew Sarah Bernhardt

by Suze Rueff

London: Frederick Muller, 240 pp. (1951) Eleanora Duse: A Biography

by Helen Sheehy

Knopf, 380 pp. (2003) Sarah Bernhardt Vue par les Nadar

by Pierre Spivakoff

Paris: Herscher, 97 pp. (1982) Biographical Essays

by Lytton Strachey

Harcourt, Brace, 295 pp. (1969) The Bernhardt Hamlet: Culture and Context

by Gerda Taranow

Peter Lang, 266 pp. (1996) Women Have Been Kind

by Lou Tellegen

Vanguard, 305 pp. (1931) Ladies, Lovers and Other People

by Elisabeth Finley Thomas and Edward C. Caswell

Longmans, Green, 279 pp. (1935) The Fabulous Life of Sarah Bernhardt

by Louis Verneuil,

translated from the French by Ernest Boyd

Harper and Brothers, 312 pp. (1942) Duse: A Biography

by William Weaver

London: Thames and Hudson, 383 pp. (1984) Shadows of the Stage

by William Winter

Macmillan, 367 pp. (1893) The Flower in Drama and Glamour: Theatre Essays and Criticism

by Stark Young

Scribner, 223 pp. (1955)