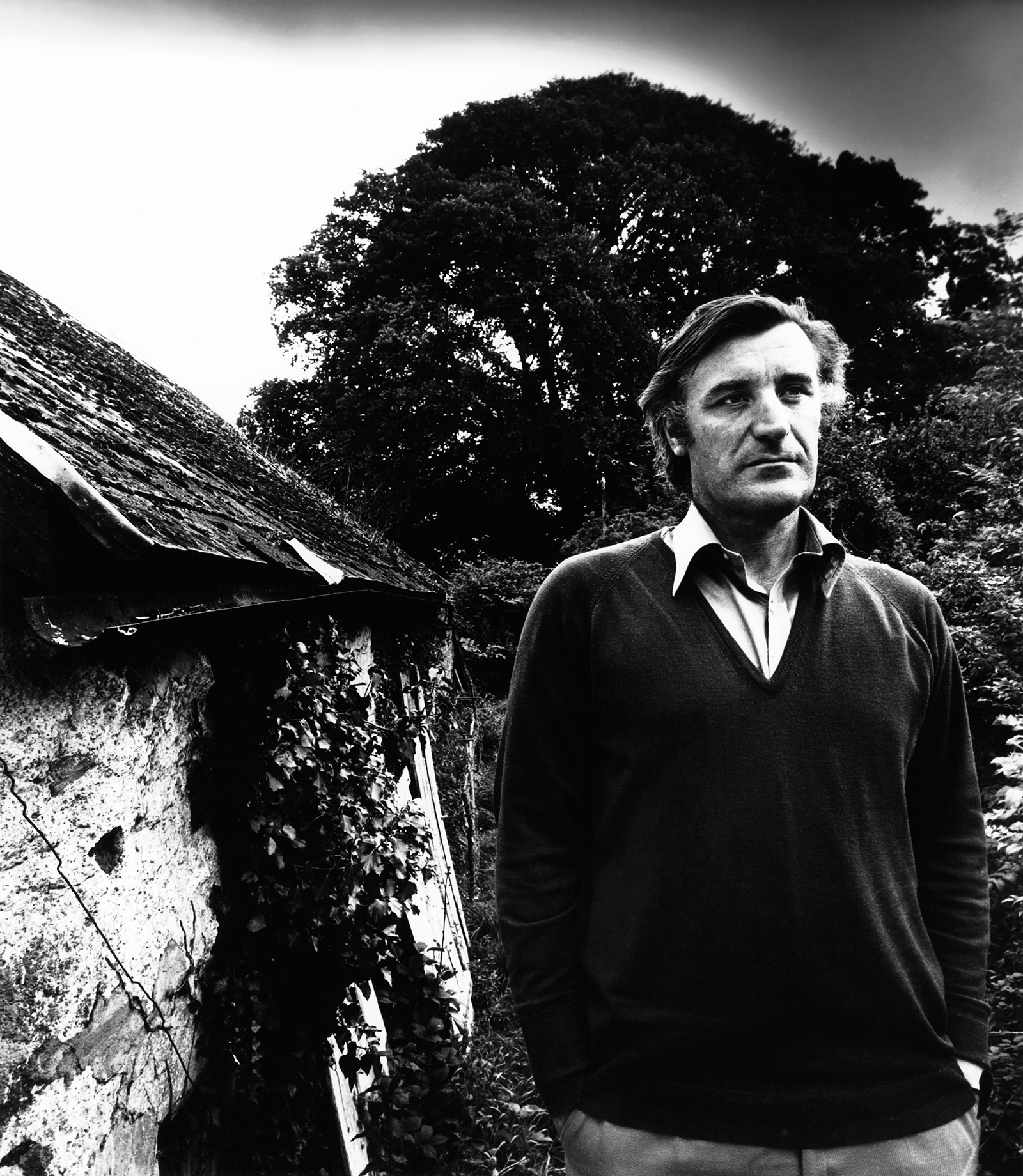

On page 313 of his biography of Ted Hughes, Jonathan Bate paraphrases a racy passage from the journal Sylvia Plath kept in the last months of her life:

On the day that she found Yeats’s house in Fitzroy Road, she rushed round in a fever of excitement to tell Al [Alvarez]. That evening, she noted in her journal with her usual acerbic wit, they were engaged in a certain activity when the telephone rang. She put her foot over his penis so that, as she phrased it, he was appropriately attired to receive the call.

We assume that Bate is paraphrasing rather than quoting Plath’s entry because of the copyright law prohibiting quotation of unpublished writing without permission of the writer or of his or her estate. As Bate wrote in The Guardian in April 2014, in an angry article entitled “How the Actions of the Ted Hughes Estate Will Change My Biography,” the estate had abruptly withdrawn permission to quote after initially enthusiastically approving “my plan for what I called ‘a literary life.’”

But in fact, the action of the estate was not the reason for Bate’s resort to paraphrase. As readers familiar with the Hughes/Plath legend will realize or have already realized, Bate was paraphrasing words he could not possibly have read since Plath’s last journal was destroyed by Hughes soon after her suicide. (“I did not want her children to have to read it,” Hughes explained when he revealed his act of destruction in the introduction to a volume of Plath’s earlier journals.) What Bate was paraphrasing, he tells us, was Olwyn Hughes’s memory of what she had read in the journal before her brother destroyed it.

In the introduction to his book, Bate—who is a professor of English literature at Oxford and the author of numerous books on Shakespeare, along with a biography of John Clare—offers a “cardinal rule” of literary biography: “The work and how it came into being is what is worth writing about, what is to be respected. The life is invoked in order to illuminate the work; the biographical impulse must be at one with the literary-critical.” And: “The task of the literary biographer is not so much to enumerate all the available facts as to select those outer circumstances and transformative moments that shape the inner life in significant ways.” But these fine words—are just fine words. The revelation, if that’s what it is, of sex between Plath and Alvarez (in his autobiographical writings Alvarez indicated that there had never been any) illuminates neither Hughes’s work nor his inner life. It only makes plain, along with his prurience, Bate’s dislike of Alvarez. “At the time of Sylvia’s death, a contemporary noted that Alvarez had a ‘hangdog adoration of T.H.’ and expressed the opinion that he was ‘stuck in Freudianism like an American teenager,’” Bate writes, and, as if this wasn’t mean enough, adds: “Alvarez could make or break a poet, but his own poetry was thin gruel.” Bate’s malice is the glue that holds his incoherent book together—malice directed at other peripheral characters but chiefly directed at its subject. Bate wants to cut Hughes down to size and does so, interestingly, by blowing him up into a kind of extra-large sex maniac.

He starts the book with a chapter called “The Deposition.” In 1986 a psychiatrist named Jane Anderson, a friend of Plath’s on whom a character in The Bell Jar had been based, sued the makers of a film version of the novel, along with Hughes (who held the copyright of the book), for portraying her as a lesbian. The lawsuit was settled. It was a nuisance and expense for Hughes, but hardly a seminal event that merits the opening chapter of his biography. The purpose of the chapter is to introduce this piece of Anderson’s testimony:

[Sylvia] said that she had met a man who was a poet, with whom she was very much in love. She went on to say that this person, whom she described as a very sadistic man, was someone she cared about a great deal…. She also said that she thought she could manage him, manage his sadistic characteristics.

Q. Was she saying that he was sadistic towards her?

A. My recollection is she described him as someone who was very sadistic.

The stage is now set for the examples of Hughes’s sadism that give Bate’s book the sensational character that caused the estate to withdraw from it in horror. The most shocking of these examples is a scene of sex in a London hotel between Hughes and Assia Wevill, the beautiful woman with whom he began an affair in the last year of his marriage to Plath, and who killed herself and her four-year-old daughter with Hughes (by gas, presumably in imitation of Plath, after living with him intermittently for five years). At the hotel, Bate writes, Hughes’s “lovemaking was ‘so violent and animal’ that he ruptured her.” Bate’s source is a diary kept by Nathaniel Tarn, a poet, anthropologist, and psychoanalyst in whom, unbeknownst to each other, Assia and her husband David Wevill confided.

Advertisement

Tarn would write down what they said to him and his papers, including the diary, found their way to an archive at Stanford University, where anyone can read them. Bate was not the first to do so. The scene of the violent and animal sex appeared in a biography of Assia Wevill, A Lover of Unreason, by Yehuda Koren and Eilat Negev. Bate writes condescendingly of Koren and Negev as “touchingly literalistic” in their interpretation of a poem of Hughes about Assia, but he is not above quoting from their interview with David Wevill in which he told them that Assia told him that Sylvia caught Hughes kissing her in the kitchen of his and Plath’s Devon house during their first visit to the couple.

Like the evidence of Olwyn’s memory, the evidence of Tarn’s diary or of David Wevill’s interview is not evidence of the highest order of trustworthiness. The standing that the blabbings of contemporaries have in biographical narratives is surely one of the genre’s most problematic conventions. People can say anything they want about a dead person. The dead cannot sue. This may be the least of their troubles, but it can be excruciating for spouses and offspring to read what they know to be untrue and not be able to do anything about it except issue complaints that fall upon uninterested ears.

Hughes’s widow Carol recently issued such a complaint, in the form of a press release written by the estate’s lawyer, Damon Parker, citing eighteen factual errors in the sixteen pages of the book she had been able to bring herself to read. The “most offensive” of these errors concerned Bate’s account of the car trip Carol Hughes and Plath and Hughes’s son Nicholas made from London to Devon with the hearse carrying Ted Hughes’s coffin: “The body was returned to Devon, the accompanying party stopping, as Ted the gastronome would have wanted, for a good lunch on the way.” Parker quotes an outraged Carol Hughes: “The idea that Nicholas and I would be enjoying a ‘good lunch’ while Ted lay dead in the hearse outside is a slur suggesting utter disrespect, and one I consider to be in extremely poor taste.”

If poor taste is uncongenial to Mrs. Hughes, she will do well to continue not reading Bate’s biography. Among the specimens of tastelessness lodged in the book like the threepenny coins in a Christmas pudding, none may surpass Bate’s quotation from Erica Jong in her book Seducing the Demon: Writing for My Life, about meeting Hughes in New York and resisting his advances (“He was fiercely sexy, with a vampirish, warlock appeal…. He did the wildman-from-the moors-thing on me full force”), after which “I taxied home to my husband on the West Side, my head full of the hottest fantasies. Of course we f—— our brains out with me imagining Ted.”

But beyond tastelessness there is Bate’s cluelessness about what you can and cannot do if you want to be regarded as an honest and serious writer. Here is what he does with an article in the Daily Mail called “Ted Hughes, My Secret Lover” by a woman from Australia named Jill Barber. Barber wrote: “His first act of love was to hold me tenderly, mopping my brow with a wet flannel as I threw up the cheap champagne into his sink…. He lay me on the bed and tenderly unbuttoned and unzipped me and gazed admiringly at me…. He was rough, passionate and forceful.” Bate writes: “He mopped her brow with a wet flannel as she threw up the cheap champagne into his sink, then he tenderly unbuttoned and unzipped her, gazed admiringly at her body and made forceful love to her.”

In 2000 Bate came to Faber and Faber, which acts as agent for the Ted Hughes estate, proposing to write an authorized biography of Hughes, who was “the obvious choice for my next literary biography after I had done with two of his favourite poets, Shakespeare and John Clare.” He was told that Hughes had left instructions opposing an authorized biography, so that was that. But in 2009, emboldened by Carol Hughes’s sale to the British Library of documents that Hughes had held back when he sold his papers to Emory University in Atlanta, and by the publication of a book of his letters, Bate approached Faber and Faber again and proposed to write not a biography, but a work of literary criticism in which the life would merely figure.1

Advertisement

This time the estate accepted. In his Guardian piece Bate recalled a delightful initial lunch with an editor from Faber and Faber and Carol (who “expressed herself ‘totally happy with my idea of using the life to illuminate the work’”) at a restaurant “in, of all places, Rugby Street—where Ted first made love to Sylvia Plath. I took this to be my symbolic anointing.” After the deal hideously unraveled, Damon Parker wrote in The Guardian:

At the risk of disillusioning him, there was no significance to the restaurant or the street chosen for a lunch with Mrs. Hughes and the poetry editor. The restaurant just happened to be a favourite haunt of Faber & Faber executives at that time. Nor was there any “symbolic anointing” of him in anyone’s mind other than his own.

The estate and Faber and Faber had begun to smell a rat early on. “The tone and style of a draft article Professor Bate wanted to submit to a respected literary magazine here soon after he was commissioned, based on his initial researches, led to concerns that he seemed to be straying from his agreed remit,” Damon Parker wrote in reply to my inquiry about what had got their wind up. (He could say nothing further about the article.) Also

despite what had been previously agreed Professor Bate then resisted repeated requests to see some of his work in progress, from that time in 2010 right up until the Estate withdrew support for his book in late 2013…. The Estate could no longer cooperate once it seemed increasingly likely that his book would be rather different in tone and content from the work of serious scholarship which he had initially proposed.

Bate and Faber and Faber parted company and HarperCollins became the book’s publisher.

Bate’s claim that withdrawal of permission to quote forced him to write the distasteful book he has written is hard to credit. In “How the Actions of the Ted Hughes Estate Will Change My Biography,” he writes of the “pages and pages of detailed analysis of the multiple drafts of the poems” that will now “have to go,” and of how “the new version will be much more biographical.” What Bate writes about Hughes’s poetry in the HarperCollins text is of staggering superficiality. He tells you what he does and doesn’t like. When he likes a poem he uses terms like “aching beauty” and “achingly sad.” When he dislikes a poem he will talk of Hughes “operating on auto-pilot, writing nature notes instead of penetrating to the forces behind nature and in himself.”

It is odd to read that last awkward phrase. Bate should be the last person to complain about the absence of unseen forces. For the mystical and mythic influences that inform Hughes’s understanding of imaginative literature and shape his poetic practice, Bate has only contempt, writing of his “sometimes bonkers ideas about astrology and the occult; his use of ancient ideas and obscure literary sources as a way of explaining, even justifying, what most reasonable people would simply describe as bad behavior.”

In a letter of 1989 to his friend Lucas Myers, published in Letters of Ted Hughes,2 Hughes writes about how “pitifully little” he is producing and goes on to

wonder sometimes if things might have gone differently without the events of 63 & 69 [the years of Plath’s and Wevill’s suicides]. I have an idea of those two episodes as giant steel doors shutting down over great parts of myself, leaving me that much less, just what was left, to live on. No doubt a more resolute artist would have penetrated the steel doors—but I believe big physical changes happen at those times, big self-anaesthesias. Maybe life isn’t long enough to wake up from them.

Hughes’s feeling of not writing enough is common among writers, sometimes even among the most prolific. In Hughes’s case it was certainly delusory. The posthumous volume of Hughes’s collected poems is over a thousand pages long and there are five volumes of prose and seven volumes of translations. But without question Hughes suffered blows greater than those it is given to most writers to suffer. His life had been ruined not just once, but twice. It has the character not of actual human existence but of a dark fable about a hero born under a malign star.

That it was Bate of all people who was chosen to write Hughes’s biography only heightens our sense of Hughes’s preternatural unluckiness; though the choice might not have surprised him. Ancient stories about innocents delivered into the hands of enemies disguised as friends were well known to him, as was The Aspern Papers. He emerges from his letters as a man blessed with a brilliant mind and a warm and open nature, who seemed to take a deeper interest in other people’s feelings and wishes than the rest of us are able to do and who never said anything trite or obvious or pious or self-serving. Of course, this is Hughes’s epistolary persona, the persona he created the way novelists create characters. The question of what he was “really” like remains unanswered, as it should. If anything is our own business, it is our pathetic native self. Biographers, in their pride, think otherwise. Readers, in their curiosity, encourage them in their impertinence. Surely Hughes’s family, if not his shade, deserve better than Bate’s squalid findings about Hughes’s sex life and priggish theories about his psychology.

This Issue

February 11, 2016

‘The EU Is on the Verge of Collapse’

The Collision Sport on Trial

-

1

As it happens, such a work had already appeared: Neil Roberts’s valuable Ted Hughes: A Literary Life (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). ↩

-

2

Selected and edited by Christopher Reid (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), beautifully reviewed in these pages by Mark Ford, November 6, 2008. ↩