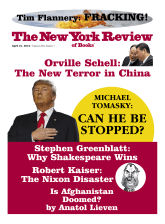

It appears to be happening. Donald John Trump is almost surely going to be the presidential nominee of the Republican Party. The man lives, according to the Daily News,1 in a three-story Louis XIV–style penthouse apartment at Fifth Avenue and 56th Street—as well as Palm Beach’s Mar-a-Lago, a sixty-room retreat in Westchester County, John Kluge’s bulging old estate in Virginia wine country, an afterthought-ish six-bedroom house in Beverly Hills, and nearly forty more Manhattan apartments that are available for his personal use. He is winning the nomination on the strength of the unshakable bond he has built with the white Republicans who consider themselves to be the most dispossessed of Americans.

It’s very clear by now that almost nothing can sunder this union. On March 3, Mitt Romney stepped forward to give a speech lambasting Trump. The 2016 front-runner, said the 2012 nominee, is “a phony, a fraud. His promises are as worthless as a degree from Trump University.” Aha, said members of the famous Republican establishment: maybe finally this will lay him low. Five days later, a poll found that the attack helped Trump—31 percent of registered GOP voters were more likely to support him in light of Romney’s speech, and just 20 percent were less likely.2

Rather more disturbing, one result of the violence that broke out on March 11 at a scheduled Trump rally on the campus of the University of Illinois at Chicago, where protesters and Trump supporters hurled epithets at one another and some fistfights took place, was that that violence also helped Trump. The candidate has spent weeks heaping verbal abuse on hecklers, walking his admirers right up to the edge of physical confrontation. On the very day that the Chicago fiasco unfolded, Trump was at a press conference in Palm Beach answering questions about violence at his rallies. Referring apparently to an earlier episode in North Carolina, where one of his white supporters sucker-punched a black protester, he said, “I thought it was very, very appropriate. [The protester] was swinging. He was hitting people. And the audience hit back. And that’s what we need a little bit more of.”

A videotape of that event had emerged, and needless to say, Trump was lying. The black protester was walking up a flight of stairs inside a sports arena with his arms at his side when seventy-eight-year-old John Franklin McGraw yelled “Hey!,” got the young man to look his way, and hit him in the face.

Monmouth University, which was conducting a poll of Republicans in Florida at the time, added a question to the survey: “As you may know, Donald Trump cancelled a rally in Chicago Friday night where protesters and his supporters got into confrontations. Does what happened there and Trump’s response to it make you more likely or less likely to support Trump, or does it have no impact on your vote for the Republican nomination?” Sixty-six percent said it would not affect their vote, but 22 percent said it made them more likely to back Trump, and only 11 percent said less likely.3

Each new outrage only confirms to his supporters that Trump is gleefully defying the establishment, and they love him for it. He lies daily, even hourly, and with complete impunity. He first vowed that he would look into paying the sucker-puncher’s legal costs; then a few days later denied he ever said that, even though it was there on video tape for all to hear. The Trump movement clearly has some elements of the fascistic, at least in affect and tone. He evidently does not call for a one-party dictatorship; but he has been willing to approve of force against the opposition; and he has expressed “belligerent nationalism, racism, and militarism,” as one basic definition has it.

Likewise, the kind of ardor he brings out in people is alarming. After Chicago, some Trump supporters took to Twitter to announce that they would be raising a private security force to “protect” Trump from the alleged hordes of violent protesters. The ugliness is undeniable and unprecedented. And yet Trump is seemingly unstoppable.

On March 15, the Trump campaign kept barreling forward, as he won states that he was half-expected to lose—Missouri, North Carolina—and destroyed Marco Rubio in Florida, chasing him from the race. He lost in Ohio, to John Kasich, but Kasich is the sitting governor of that state, with an approval rating above 60 percent. He might prove able to compete against Trump in some other states, mostly in the Ohio region; but he might also prove to be no more than a favorite-son candidate capable of winning his own state. Besides, Kasich’s continued presence in the race, alongside that of Ted Cruz, means that the GOP primary will remain a three-way contest, quite possibly through June, which in turn means that Trump can win important winner-take-all primaries with 34 percent of the vote and not the harder-to-attain, and more legitimizing, 51 percent.

Advertisement

As for whether he can win a majority of delegates, the picture was still unclear after the March 15 voting. Harry Enten of the website FiveThirtyEight, which specializes in crunching political numbers, estimated on March 16 that Trump would fall just short of the 1,237 delegates needed to clinch the nomination.4 Enten noted that Trump had won 47 percent of the delegates allocated up to that point but would need to win 54 percent in the remaining contests to attain the magic number.

Trump of course knew this and, that same morning on CNN, delivered what may be his most chilling observation yet, a title for which the competition is stiff indeed, but consider:

I think we’ll win before getting to the convention, but I can tell you, if we didn’t and if we’re twenty votes short or if we’re a hundred short and we’re at 1,100 and somebody else is at five hundred or four hundred, because we’re way ahead of everybody, I don’t think you can say that we don’t get it automatically. I think it would be—I think you’d have riots…. If you disenfranchise those people and you say, well I’m sorry but you’re a hundred votes short, even though the next one is five hundred votes short, I think you would have problems like you’ve never seen before. I think bad things would happen, I really do. I believe that.

He added that he “wouldn’t lead it,” but of course he just had.

There is a rule in journalism that we should avoid comparisons with Hitler, and it’s a useful rule in general. But at the same time we should be alert to the history that is unfolding before our eyes. Without likening Trump personally to the Austrian corporal, let us at least not ignore certain similarities in their ascents to power. Writing about Hitler’s assumption of the chancellorship, Oswald Spengler observed: “That was no victory, for there were no opponents.”5 Something similar may be said today of two entities, the Republican Party and the media, especially television.

As long ago as last November, I was hearing from conservative sources that the big Republican money people were drawing up plans to mount an extensive campaign of attack ads against Trump designed to finish him off before Iowa. I was told that a few such meetings or conference calls took place. But nothing ever came of them. The different players had different ambitions, supported different candidates, or couldn’t agree on the best lines of attack.

The Republican Party itself, and chairman Reince Priebus, have been mostly feckless. The man who is on the cusp of winning their nomination has the open support of white supremacists. He has retweeted neo-Nazis. He hedged on distancing himself from the Ku Klux Klan. He has proven himself to be beneath the office in nearly every way imaginable. And yet leading Republicans hardly acknowledge these matters. The racial politics Trump has brought to the surface is something the party is particularly incapable of dealing with, since they all must know deep down that he is only doing openly what they have done more subtly for decades.

Trump’s primary opponents have in fairness used much tougher rhetoric against him. But they also did him a tremendous favor by staying in the race as long as they all did, splitting the anti-Trump vote. There was likely nothing to be done about this—each opponent, obviously, thought or thinks that his anti-Trump case is the strongest, and of course each wants to be president. That said, it must be understood that these men—Cruz, Kasich, Rubio, and Jeb Bush—all made a choice. They knew very well that by continuing to compete long after it was clear that the party should rally around one figure and hope for the best, they were clearing Trump’s path to the nomination.

Finally, the media. All of us who appear with regularity on any of the cable news channels have become familiar with the same phenomenon. If you’re scheduled to do a segment at a certain time and date, and it becomes apparent once you get to the studio that Trump might be speaking at any moment, you know there’s a very strong chance your segment won’t happen. The channel will cut away to Trump.

On primary nights, this is even more pronounced. On March 8, when Trump won in Michigan and Mississippi and Bernie Sanders scored his upset in Michigan, all three cable networks carried Trump’s full forty-five-minute, rambling monologue (such election-night speeches usually run around fifteen minutes). They skipped over Hillary Clinton’s and John Kasich’s speeches, although MSNBC broadcast Clinton’s speech in its entirety—but only on tape delay, after Trump was finished.6

Advertisement

In mid-March, mediaQuant, a firm that tracks media coverage of candidates and assigns a dollar value to that coverage based on advertising rates, compared how much each candidate had spent on “paid” media (television ads) and how much each candidate had been given in “free” media (news coverage). Bush, for example, had spent $82 million on paid media and received $214 million in free media. For Rubio, those respective numbers were $55 million and $204 million. For Cruz, $22 million and $313 million. For Sanders, $28 million and $321 million. For Clinton, $28 million and $746 million (in her case, much of that free media was negative, relating to the State Department e-mails).

And Trump? He’d spent not more than $10 million on paid media and received $1.9 billion in free media. That’s nearly triple the other three major Republican candidates combined.7

CBS head Les Moonves, who joined what was once called the Tiffany Network as head of the entertainment division in the 1980s and who lately has been pulling down around $60 million a year in compensation, let the cat out of the bag when he spoke in late February at something called the Morgan Stanley Technology, Media, and Telecom Conference in San Francisco. This is not a meeting dedicated to a discussion of news gathering as a public trust. Rather, it is a convocation at which Morgan Stanley analysts discuss how, “from virtual and augmented reality to 5G and autonomous cars, the pulse of digital experience is speeding up” (so says the conference website). And it was here that Moonves said that the Trump phenomenon “may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” adding:

Man, who would have expected the ride we’re all having right now?… The money’s rolling in and this is fun…. I’ve never seen anything like this, and this is going to be a very good year for us. Sorry. It’s a terrible thing to say. But, bring it on, Donald. Keep going. Donald’s place in this election is a good thing.8

Eleven days later, a CBS reporter got caught in the middle of the mayhem at the Trump Chicago event and was thrown to the ground and arrested.

On the Democratic side, the Ides of March took most but not quite all of the drama out of the proceedings. Bernie Sanders’s win the week before in Michigan was, arguably, the biggest upset in the history of modern presidential primaries.9 That Sanders could win in a large, diverse, and clearly important state appeared to have the potential to reshape the race radically. Sanders attacked Clinton effectively on the ill effects on employment of trade deals, which she had supported throughout her career until her recent turnabout on the Trans-Pacific Partnership. She had no answer. Clinton had also been hurt in Michigan by the fact that her lead seemed so insurmountable—twenty-plus points—that many of her voters either stayed home or decided to vote Republican to block Trump (it was an open primary).

So Democrats were braced for a March 15 result that kept the waters muddy, but instead, they cleared up. Clinton won all five contests. The biggest surprise came in Ohio, which she had led narrowly but ended up winning by a startling 57 to 43 percent. Sanders was supposed to have strength in the state’s whiter, more rural areas—oddly enough, exactly the areas where she had throttled Barack Obama eight years ago. But he carried only thirteen of Ohio’s eighty-eight counties. And among nonwhite voters, Clinton continues to benefit from the higher incomes blacks and other minorities achieved under Bill Clinton’s administration.

People puzzled over how Ohio could have been so different from Michigan. One explanation may be that Ohioans simply don’t feel as gutted by deindustrialization as Michiganders do. But I think that Joshua Holland, studying the exit polls and writing in The Nation, put his finger on something that may have been a bigger factor. The Chicago riot happened between Michigan and Ohio. It seems possible that what Democrats saw on their television screens scared them into rethinking their suppositions about the campaign and caused them to lean more in the direction of choosing the candidate they considered better able to beat Trump10:

Exit polls show that on March 15, Clinton’s argument won the day with primary voters. Across all five states, two-thirds of them said that Clinton was the better bet to defeat Donald Trump, and Clinton won the support of 80 percent of those who said that electability and experience were the most important attribute in a candidate.

The Sanders people would argue with that—and did, vigorously, but apparently not persuasively. He will continue to win contests. In particular, he’ll sweep the caucuses in the red states, because the only Democrats left in places like Utah and Idaho—where Sanders thumped Clinton on March 22, as she easily carried the more important Arizona—are trial lawyers, college professors, teachers, and hipsters who’ve managed to carve out their little slice of bohemia even in Salt Lake City and Boise. He will have the money to make heavy advertising buys, and he will continue to draw large crowds, and he may yet win a surprising state or two or even three. But the argument he was making before March 15—that in fact he had demonstrated more national appeal than Clinton had—was rendered moot.

Most of all, the delegate numbers are such that, observers agree, he cannot catch up. The magic number on the Democratic side is 2,383. The Democrats also have “superdelegates,” which the Republicans do not—roughly seven hundred elected officials and Democratic National Committee members who each get a delegate vote. Superdelegates exist on the Democratic side because, after the party radically democratized its nomination process in the 1970s, some began to fret that the party had introduced a little too much democracy and decided to create a mechanism whereby the party elders still had some say in the nomination.

Many of these grandees have already endorsed Clinton, and few have backed Sanders. But what the superdelegates really do in the end is validate the voters’ selection. They have little choice. Can you imagine the controversy that would explode if Candidate A had amassed 2,100 delegates and Candidate B 1,800, but the party panjandrums collectively threw the nomination to Candidate B? This validation of a leader worked to Clinton’s detriment in 2008, when Barack Obama led her narrowly among amassed delegates, and there was no chance the superdelegates were going to take the nomination out of the hands of the party’s first African-American nominee.

This year, it will work to her advantage. Before March 15, Sanders said repeatedly that superdelegates must honor the decisions of the voters. Online petitions were launched to that effect that immediately drew tens of thousands of signatures. At that point Sanders was anticipating the prospect of winning more states but was still facing the opposition of the party elites. But after the March 15 results, Sanders’s argument works in favor of Clinton.11

The question during the spring and summer will be the extent to which Sanders decides to cooperate with the party of which he’s never been a member in confirming the choice of a candidate whose views on some of the issues he cares most about are anathema to him. My mind races back to 1992 and the curiously similar situation involving the current front-runner’s husband and Jerry Brown. The California governor is now a (somewhat) mellowed septuagenarian. But Brown in 1992 had fashioned himself the left-leaning insurgent candidate. Then as now, a Clinton got the better of the insurgent, more or less locking things up by mid-March. Brown did not go away gently. He refused to endorse Bill Clinton during the primaries. His speaking spot at the convention was hotly debated, but he was given one, and even then he refused to endorse Clinton; he didn’t even mention his name. What will Bernie do? So far, most of his criticisms of Clinton have been on policy from the left. If he starts attacking her integrity, say—that is, foreshadowing attacks the Republicans will make this fall—he will have crossed an unfortunate line.

Clinton has made some formally friendly statements about Sanders. She will need his ungrudging approbation. Among younger voters, Sanders has beaten her by about four to one. These voters have no living memory of her tenure as First Lady, of the right-wing witch hunt against her, or of the ways in which she was a mold-breaking first spouse. They have no wish to recognize why the 1994 crime bill, vilified in our times by the Black Lives Matter movement as racist, might have seemed a necessary and acceptable compromise then.12 She has shown, shall we say, a limited capacity to communicate these matters to younger voters. She will require his help to get a healthy turnout among them.

It is conceivable—not more than that—that Trump can be stopped. He would need to end the primary season short of the support of a majority of delegates—which means, probably, that Kasich must beat him in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Indiana, and even California, an unlikely outcome. At the convention pledged delegates are released after the first ballot. If he does not win on that ballot and public opinion polls at that time are showing that Kasich would be a stronger candidate against Clinton than Trump would—as they surely will—then one can imagine panicked Republicans risking the wrath of Trump and his angry army by changing their votes and turning against him. But it seems a long shot. He will be so far ahead. The rules are the rules. But if we’ve learned anything this year, it’s that Trump can change the rules.

Some Republicans and conservative activists are also trying to hatch an independent conservative candidacy. There are many obstacles to such a scheme, starting with how many state ballots such a candidate could qualify for, and ending with the question of whether such a person wouldn’t simply ensure a Clinton victory by splitting the center-right vote.

It would seem that Clinton should be able to beat Trump. In recent polls matching the two of them against each other, she leads him consistently—nationally by eight or nine points, and in crucial states by fairly comfortable margins, like eight in Florida and five or six in Ohio.13 A number of Republicans would declare for her—including remaining moderates, and foreign policy neoconservatives, who fear Trump’s wanton tendencies and hope against hope that Clinton is an ally (about this they are wrong), or will, in sponsoring more assertive policies abroad, at least be more palatable from their perspective than Obama (about this they are alas right). Latino turnout against Trump should set records.

But it’s quite early for all such speculations. The more immediate concern is how much more deeply Trump can distort the political process. That process certainly wasn’t anything to brag about pre-Trump, and as frightening as he is, he has made a few observations that are true and reasonable, notably that the political system has been utterly incapable of doing anything for at least the last fifteen years to help most of the people who have flocked to him.

Clinton should be mindful of these spare legitimate strands of Trumpismus, strands that Sanders in his very different way has sought to identify and appeal to, and think of ways to reach the millions of people who live in shelled-out communities and have made no economic progress. Many, probably most of them, are motivated more by hate and fear, and they’ll stick with Trump. But it would still be an error to write them off. That will only push them en bloc into the demagogue’s embrace. He shouldn’t be allowed to win any more victories for lack of opponents.

-

1

See Katherine Clarke, “Take a Peek Inside Donald Trump’s Vast Portfolio of Private Homes,” New York Daily News, July 27, 2015. ↩

-

2

See Donovan Slack, “Poll: Romney Helps More Than Hurts Trump with Republicans,” USA Today, March 8, 2016. ↩

-

3

See Philip Bump, “Surprise! Voters Don’t Seem to Hold Violence at Trump Rallies Against Him,” The Washington Post, March 14, 2016. ↩

-

4

See Harry Enten, “It’s Still Not Clear That Donald Trump Will Get a Majority of Delegates,” FiveThirtyEight, March 16, 2016. ↩

-

5

Quoted in Joachim C. Fest, Hitler (Harcourt Brace, 1974), p. 387. ↩

-

6

See Hadas Gold, “Trump Infomercial Captivates Networks,” Politico, March 9, 2016. ↩

-

7

See, for example, Nicholas Confessore and Karen Yourish, “Measuring Donald Trump’s Mammoth Advantage in Free Media,” The New York Times, March 15, 2016. ↩

-

8

See Paul Bond, “Leslie Moonves on Donald Trump: ‘It May Not Be Good for America, But It’s Damn Good for CBS,’” The Hollywood Reporter, February 29, 2016. ↩

-

9

So suggested FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver, who tweeted the night of March 8 that the Sanders win was on track to be an even bigger upset than Gary Hart’s 1984 victory in New Hampshire over Walter Mondale, which Silver said had held the record for being at greatest variance with the pre-balloting polls. ↩

-

10

See Joshua Holland, “Did the Chaos and Violence at Trump’s Rallies Push Clinton Over the Top on Tuesday?” The Nation, March 16, 2016. ↩

-

11

There is a further irony here in the fact that Tad Devine, Sanders’s top strategist, participated in devising the superdelegate scheme after the 1980 election. ↩

-

12

The crime bill passed in 1994, when crime rates were much higher than today. In the House of Representatives, for example, about three quarters of all Democrats (188–64) and two thirds of the members of the Congressional Black Caucus (23–11) voted for the bill. Bernie Sanders voted for it as well. ↩

-

13

270towin.com allows the visitor to focus on possible head-to-head matchups, and my national numbers come from that site. RealClearPolitics posts all the latest polls; my Florida and Ohio numbers are from there. ↩