London. Late summer, 2015. The city’s habitual pearly gray daylight adds, it seems, an extra layer or patina of ardor and melancholy to the Canadian-born Agnes Martin’s extraordinary mid-to-late-career paintings—images made, for the most part, on square canvases measuring seventy-two inches, and filled with stripes of varying widths and hues that remain, twelve years after Martin’s death in 2004, at age ninety-two, some of the more significant creations about spirituality, beauty, and painting itself that modernism has ever known.

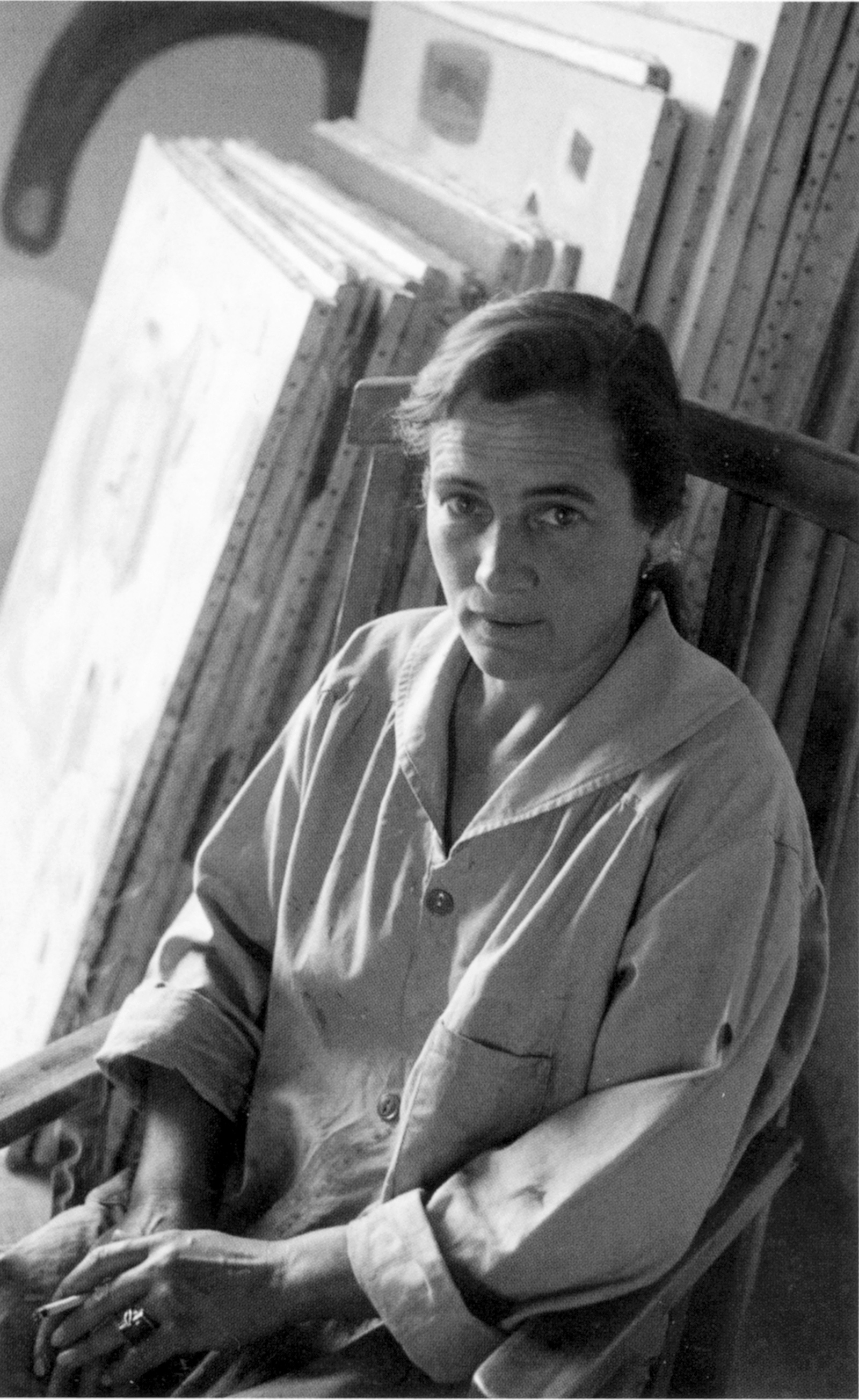

There’s a literary cast to Martin’s biography—the accidental and willed isolation of it—that reminds one of Christian carrying his burdens to the Wicket Gate, seeking enlightenment in John Bunyan’s religious allegory, The Pilgrim’s Progress, a text that exercised a considerable influence on Martin as a child. Born in Macklin, Saskatchewan, in 1912, she was the third of four children; her parents, Malcolm and Margaret Martin, farmed the vast, sometimes hard land. “It was so flat, you know, you could see the curves of the earth,” Martin recalled in Mary Lance’s intimate documentary, With My Back to the World (2002). “And when a train came into vision at nine o’clock in the morning, it was still leaving at noon…it took that long to get across the prairie.”

By the time she was three, Martin’s father had died, according to one of several accounts, from injuries suffered during the Second Boer War, which had ended in 1902. After his death, the apparently hard and embittered Margaret moved her family a few hours east to Lumsden, where the remaining Martins settled, for a time, with Robert Kinnon, Margaret’s widowed father. The Scotch Presbyterian farmer was the young Martin’s first experience of love. “I felt ‘first’ with my grandfather,” Martin said to her last dealer, Arne Glimcher, a memory he includes in his cumbersome but visually interesting book.1 Martin continued: “I’ve never felt first with anybody else…. He was a man who tried to be virtuous, really tried…. He influenced me tremendously.”

Kinnon read, with Martin, the Bible, The Pilgrim’s Progress, and other religious texts. Kinnon’s arm’s-length ministrations (he was not physically affectionate) did not so much act as an antidote to Margaret’s coldness as become the kind of distance his granddaughter could bear—and eventually emulate. But in Margaret’s presence Martin felt a sense of constant defeat and, because of her mother, was forced to take self-reliance to a punishing, perverse degree. When Martin was six she suffered from tonsillitis. The most Margaret could manage by way of comfort was to give her daughter money for the streetcar; she’d have to deal with it on her own. She did, and, after the operation was performed, returned home, again by streetcar, alone.

In 1919 the Martins joined Robert Kinnon in Vancouver, where Margaret supported the family by buying, renovating, and reselling houses. As close as Martin was to one brother, she avoided after-school walks home with her siblings; already she tended to avoid any form of social life that distracted her from examining the state of her own mind and that which it fixed on at the time: looking at pictures, drawing, and swimming. As an adolescent Martin developed into a strong swimmer and qualified for the Canadian Olympic swimming team. “The rigors and routines of competitive swimming and, perhaps most strikingly, its combination of ambition and solitude, are all habits Martin would sustain,” writes Nancy Princenthal in her strange book—a biography whose subject is so resistant to being known that Princenthal’s work feels more like a sketch than a completed portrait. Added to that is Princenthal’s Martin-like scrupulosity. (The design of the book doesn’t help, either, especially the index; the print is so tiny there you need a magnifying glass to read it.) She does not enliven the narrative with the distracting what-ifs and maybes that can and often do give biographies a little oomph.

Instead, she leans too heavily on the “telling” bits of information—the real-life metaphors—that she assumes make Martin more lifelike, especially when it comes to her fabled iconoclasm. To wit: “More than in any other organized athletic pursuit, swimmers, even when part of a team, are profoundly alone when they practice and compete.” Had Martin not been a woman, would her “profoundly alone” persona have generated so much interest? And so much useless and ultimately romantic speculation about what it might mean? Elizabeth Hardwick articulated the status quo’s reaction to certain independent women when she wrote of how negatively they were perceived, wandering about “in their dreadful freedom like old oxen left behind, totally unprovided for.”

Martin was having none of that. “We have been very strenuously conditioned against solitude,” she observes in her wonderful collection of writing. “To be alone is considered to be a grievous and dangerous condition…. I suggest that people who like to be alone, who walk alone will perhaps be serious workers in the art field.”2 Being an art worker was, she felt, a privilege, and one’s apprenticeship took as long as it took; art was not a race. “To live truly and effectively the idea of achievement must be given up,” she wrote in 1981 in an open letter to the Whitney Museum of American Art. Put unsentimental piety first, turn your back on the world, and get on with it.

Advertisement

As an adolescent, during the early days of the Depression, Martin moved to Bellingham, Washington, to help care for a pregnant sister. After graduating from a local high school she enrolled, in 1933, in Washington State Normal School at Bellingham. She graduated three years later. After teaching in various public schools in Washington, Martin briefly accepted a swimming scholarship to UCLA before dropping out and moving, in 1941, to New York, to attend Columbia University’s Teachers College, where she studied fine arts and arts education.

Becoming a teacher was one way to serve the world or the memory of her mother or both. “Sounds like bragging but I think the best work I’ve done is as a disciplinarian,” Martin said in a 1989 interview with the historian Suzan Campbell. “I think I inherited that from my mother. I’m just a natural.” (Discipline, the question of or the need for it, is a recurring theme in Martin’s writing. “The authority-obedience state of being is not a ‘sometimes’ state but a continuous state of being. We are always in authority and always in obedience,” Martin wrote in 1977. Four years before that the critic and memoirist Jill Johnston published her remarkable essay, “Agnes Martin: Surrender and Solitude.” In it, Johnston describes a conversation she had with Martin: “she said she wanted to ask me something…it was certainly a difficult moment…all i can say is it concerned domination and i think whether i hadn’t experienced domination or being dominating. i thought possibly she was alluding to women as role players.”) After graduating in 1942, she continued to support herself teaching art to high school students while also working, variously, as a tennis coach, a waitress, a baker’s helper, and a dishwasher. “Whenever I was really starving I always washed dishes because I got closer to the food.” It wasn’t until she was thirty that she determined to become an artist herself.

The earliest pieces in the current retrospective—which opened in London last summer and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art this spring—are from 1952, by which time Martin had become a naturalized American citizen and, despite moving a great deal between the east and west coasts, had more or less settled in Taos, New Mexico. (She would call the place home from 1946 to 1957 or so.) And yet it’s interesting to look at plates in Princenthal’s book of Martin’s work before she started producing art in a more abstract vernacular, if only to see what she left behind and took with her as she struggled to attain her own style. The postwar images owe a great deal to the French Expressionist painter Georges Rouault and, to a certain extent, John Marin, the American Expressionist, whose lush but controlled watercolors evoke the rush and chaos of the natural world. (Marin was particularly fine when rendering water.)

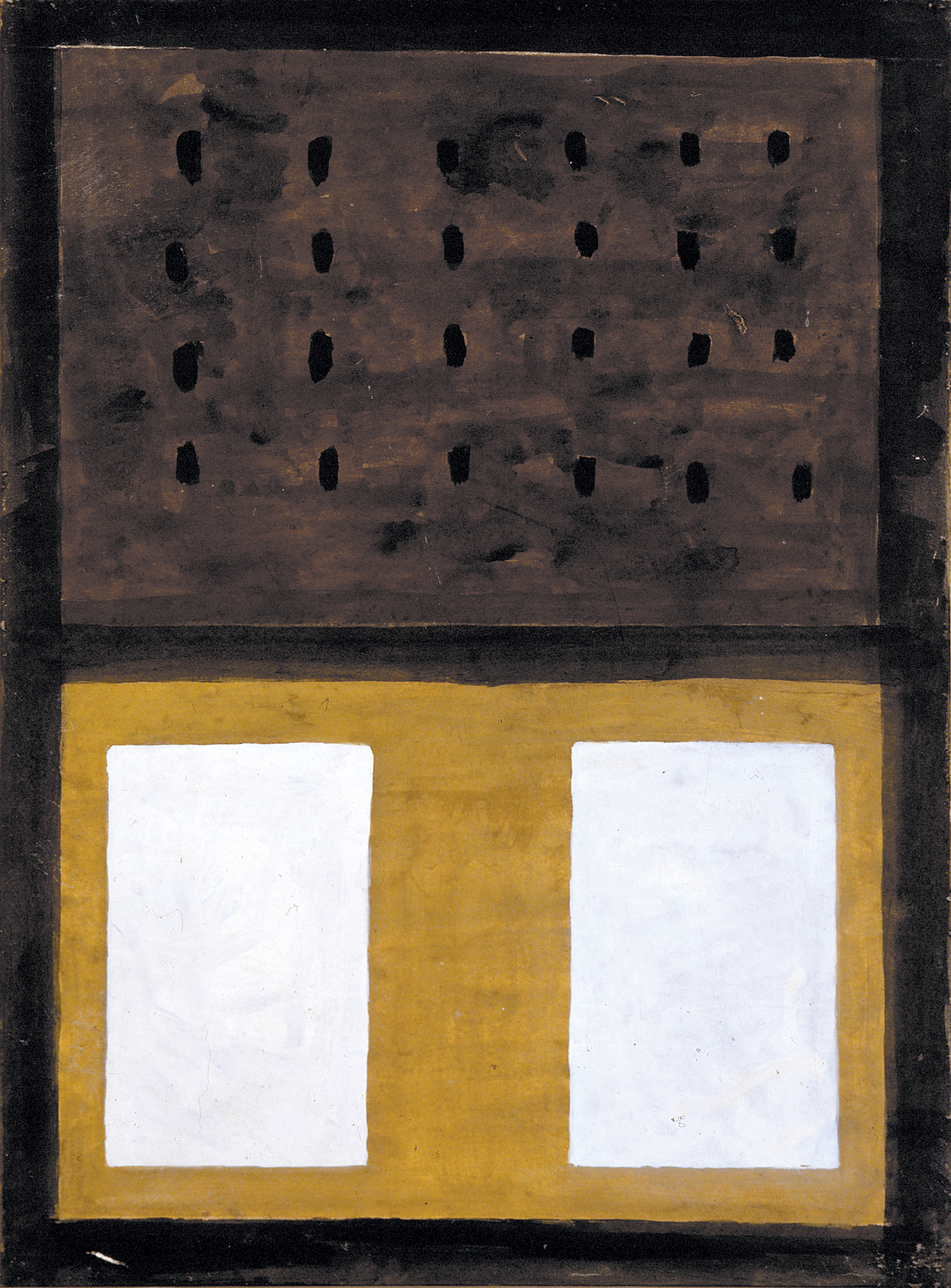

Martin’s awkward early mountain scenes and Nude (1947), a small canvas that depicts a topless, tawny woman sporting hoop earrings, display a certain interesting energy, but these images are illustrations, not paintings. Even as her work moved away from the representational to the abstract—a shift that started in 1949 with dull, muddy pieces, such as that year’s Untitled—a heaviness pervades the work, as if Martin could not shake her influences and struggled with their weight. Eventually she worked through her post-Marin influences, such as Abstract Expressionist stars like Adolph Gottlieb and Stuart Davis, but it took years—years where she destroyed canvas after canvas. Tiffany Bell and Frances Morris—the loving curators who put the London survey of her work together—include 1954’s Untitled, with its Adolph Gottlieb–like shapes and a few other paintings of its kind, the better to show what it looked like as Martin moved away from the body and into drawing something more ineffable—nature, or more specifically, the cosmos at the heart of the natural world.

Walking through the show, one can see how ultimately unsuited Martin was to be a hard-core Abstract Expressionist; the movement was too noisy, and what did she have to do with bop, the Beats, that wall of sound and bodies that wanted to shout the squares down in favor of “kicks”? Martin was interested not in discord but in harmony. While Jackson Pollock said he was nature, Martin strove to represent how nature made her feel or should make us feel—humble, free. Nature was to her what it was to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “transparent eye” in his transcendentalist masterpiece, “Nature” (1836)—a space unrivaled in its ability to inspire and transform.

Advertisement

Emerson’s idealism—“Nature is made to conspire with spirit to emancipate us”—was not unlike Martin’s. Often, in her lovely, empathic writing, she tries to communicate what being an artist must mean if one is going to make real work: becoming a conduit of the beautiful, that which cannot be explained. In her 1989 piece, “Beauty Is the Mystery of Life,” Martin wrote:

When a beautiful rose dies beauty does not die because it is not really in the rose. Beauty is an awareness in the mind. It is a mental and emotional response that we make. We respond to life as though it were perfect. When we go into a forest we do not see the fallen rotting trees. We are inspired by a multitude of uprising trees…. The goal of life is happiness and to respond to life as though it were perfect is the way to happiness. It is also the way to positive art work.

Still, Martin would not be able to create “positive” artwork for years to come; the journey was long. Despite the strong presence of artists like Franz Kline in her abstractions of the early-to-mid-1950s, Betty Parsons, the legendary Manhattan-based art dealer, saw enough in Martin’s canvases to take her on in 1957; she also encouraged the artist to move to New York.

Parsons was right. By the time Martin settled in her loft on South Street, near the East River, in 1961, she’d found her own way, become her own master. Martin was one of the few women on the scene in Coenties Slip, a world that was dominated by gay men, including Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Ellsworth Kelly. Princenthal writes well about the milieu, and how Kelly, along with Lenore Tawney, a weaver and collagist, befriended the withdrawn Martin. (Tawney may have been a lover of Martin’s as well.) Certainly this reasonably safe “queer” environment contributed to Martin’s becoming more herself. Living among younger artists who made work that challenged the painters Martin grew up revering no doubt encouraged her to find her way, too.

Princenthal discusses Tawney’s love of order and line as a possible influence on Martin’s early grids, but I think Martin’s emotionally distant neighbor, Jasper Johns, must have helped point her in her new direction as well, and by example: his painting Gray Numbers (1958) and drawing 0–9 (1960) are rooted in the grid and, by extension, in a conception of the modern, certainly as defined by the art historian Rosalind Krauss. (Of course Martin was not by that point interested in numbers, or indeed anything remotely recognizable. She preferred work that was, she said, “free from any expression of the environment.”)

Still, finding the grid was important. In her seminal 1979 essay, “Grids,” Krauss writes that the grid emphasized the “modernity of modern art,” with its emphasis on the thing as opposed to representation.3 The grid, Krauss wrote, was framed by the “will to silence,…hostility to literature, to narrative, to discourse” while rejecting the “shame” of belief or religiosity. In the world of modern art, for Krauss, there was only making—and change through destruction. (Rauschenberg’s assemblages could be viewed as artifacts of making and unmaking in a single piece.)

Martin contradicted all that nihilism. She used the grid as a forum for belief—a space where the viewer as well as the artist could contemplate the hand making the thing being observed. In her well-considered 1971 appreciation of the artist, Kasha Linville wrote:

Once you are caught in one of her paintings, it is an almost painful effort to pull back from the private experience she triggers to examine the way the picture is made. The desire to simply let yourself flow through it, or let it flow through you, is much stronger…. Her paintings exert themselves differently, depending on their line, their pattern, and the quality of the ground color on the canvas. Some are less lyrical, evincing aggression or tension…. Others suggest spaciousness or vast space, again without using illusionistic devices or the egotistical implication of infinitely extendible surface.

One pauses at the extraordinary line “the egotistical implication of infinitely extendible surface.” Unlike her male predecessors, not to mention contemporaries, Martin didn’t use the grid as a means of describing the infinite—the infinite “I” of being an artist. Instead, her work ends at the canvases’ edge.One begins and then one finishes; the grace is in the doing. Her touch was her personality; looking at canvases such as Friendship, of 1963 (made of incised gold leaf), or the ghostly Grass of 1967, one sees various lines that begin with verve, grow faint and then run out, slowly and calmly, like a swimmer beginning strong and then using wide, unhurried strokes once they see the shore. “Line is where she speaks most personally,” Linville said. “It is her vocabulary as the grids are her syntax.”

As Martin found her voice as an artist, she began hearing voices. In 1962 she suffered her first schizophrenic episode. (She was afflicted by the disease for the rest of her life. Eventually, with the help of a sympathetic doctor who collected her work, she was able to manage it.) Perhaps prompted by what she would call “her voices,” Martin stopped painting in 1967 and left New York. (Before leaving town she wrote to the curator Sam Wagstaff, who was then working at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford: “I am staying unsettled and trying not to talk for three years. I want to do it very much.”)

For the next eighteen months the painter traveled around the US and Canada in a pickup truck. At the end of 1968, beginning of 1969, she resettled on a mesa outside Cuba, New Mexico, before building a home and studio in Galisteo where she lived for the rest of her life without radio, television, or newspapers: the world’s babble was a distraction from sharpening one’s vision. “When we realize that we can see life we gradually give up the things that stand in the way of our complete awareness,” she wrote in her 1989 piece for Artspace, “The Current of the River of Life Moves Us.” “As we paint we move along step by step. We realize that we are guided in our work by awareness of life.”

Morris and Bell’s show is a commendable map that reveals Martin making her way, step by step, her pilgrim-like progress measured against all those flat skies, fields, trees, bodies of water, barely expressed emotions that made up her home. Before she left New York and gave up making work for seven years, Martin made a series of drawings and paintings, starting in 1963, that bled color out of her art. The horizontal grays of Morning (1965) and Grass (1967) are as solid as the sky—or rutted earth—and, like Tundra (1967), the last canvas she completed before she gave away most of her possessions, are opaque and specific, all at the same time. In those works and others she was trying to make mystery a solid object. When she returned to her art in 1973, the title she gave to the graphically strong, stark, black-and-white prints she produced first said it all, certainly with respect to the atmosphere that New Mexico could provide her with, day after day as she worked out there, blissfully alone: On a Clear Day.