Characterized by the caprice and fatalism of fairy tales, the fiction of Shirley Jackson exerts a mordant, hypnotic spell. No matter how many times one has read “The Lottery,” Jackson’s most anthologized story and one of the classic works of American gothic literature, one is never quite prepared for its slow-gathering momentum, the way in which what appears initially to be random and casual is revealed to be as inevitable as water circling a drain. As the stark title “The Lottery” suggests an impersonal phenomenon, the story’s perspective is detached and reportorial; a kind of collective consciousness emerges from the inhabitants of a small unnamed New England–seeming town that finds expression in tonally neutral commentary reminiscent of Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony”:

The original paraphernalia for the lottery had been lost long ago, and the black box now resting on the stool had been put into use even before Old Man Warner, the oldest man in town, was born…. Because so much of the ritual had been forgotten or discarded, Mr. Summers [the “official” of the lottery] had been successful in having slips of paper substituted for the chips of wood that had been used for generations…. At one time, some people remembered, there had been a recital of some sort, performed by the official of the lottery, a perfunctory, tuneless chant that had been rattled off duly each year….

This consciousness is as visually selective as a cinematic camera eye, noting

for us, already in the second paragraph, ominous details amid so much that is ordinary, even banal: “Bobby Martin had already stuffed his pockets full of stones, and the other boys soon followed his example….”

Though we experience the crucial portion of the story through the eyes of the near-anonymous Mrs. Hutchinson, we never become acquainted with the housewife and mother who is to be sacrificed on the “full-summer day” in late June. Jackson’s protagonist, presumably a longtime resident of the village, should know exactly what is impending, if not for herself then for a neighbor or a relative, yet a curious amnesia seems to define her, as it defines her fellow villagers. A yearly ritual of sacrifice would have traumatized survivors but the families of Jackson’s village seem oddly intact and a vague unease is all that is suggested of trauma; children cheerfully gather stones that they may use to stone their own mothers, as if so abrupt an absence in a household could have no actual consequence. Unlike Jackson’s more subtly modulated and psychologically complex fiction (“The Daemon Lover,” “The Tooth,” “The Lovely House,” The Haunting of Hill House, We Have Always Lived in the Castle), “The Lottery” skims along, bound for a jarring climax, in the O. Henry tradition, and beyond that no tidying-up conclusion:

Tessie Hutchinson was in the center of a cleared space by now, and she held her hands out desperately as the villagers moved in on her. “It isn’t fair,” she said. A stone hit her on the side of the head.

Old Man Warner was saying, “Come on, come on, everyone.” Steve Adams was in the front of the crowd of villagers, with Mrs. Graves beside him.

“It isn’t fair, it isn’t right,” Mrs. Hutchinson screamed, and then they were upon her.

Unwittingly, we have seemed to participate in the last minutes of a woman’s life with no more anticipation than she had of what was imminent. Nor is there any suggestion that the victim will be missed, still less mourned, even by her family:

In this village, where there were only about three hundred people, the whole lottery took less than two hours, so it could begin at ten o’clock in the morning and still be through in time to allow the villagers to get home for noon dinner.

No one speculates on the meaning of the lottery, and no one seems much interested in its origin. Is Jackson’s story social satire, religious allegory, a resolutely unglamorous reimagining of ancient fertility rites? There is no explanation for what happens, except that it has happened before and is mandated to happen again.

Allegedly written quickly by Shirley Jackson in March 1948, at the age of thirty-two, and only minimally revised, “The Lottery” appeared in the June 26, 1948, issue of The New Yorker and precipitated a “torrent of letters” and attention, much of it scandalized and antagonistic; the bemused author kept a giant scrapbook (now preserved in her archive in the Library of Congress) containing nearly 150 letters from the summer of 1948 alone. That many of its original readers considered “The Lottery” to be nonfiction can be attributed to The New Yorker’s disinclination to identify fiction and nonfiction as it does today; a number of readers were frankly baffled, and a number huffily canceled their subscriptions.

Advertisement

It is true that, as Ruth Franklin notes in her appropriately titled biography Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, the victim of the lottery is “chosen at random”; yet it hardly seems accidental that Mrs. Hutchinson happens to be a housewife and a mother, so distracted by domestic tasks that she nearly misses the lottery: “Wouldn’t have me leave m’dishes in the sink, now, would you, Joe?” The story was written while Jackson was pregnant with her third child and preoccupied with care of her young children and her very demanding husband; published more than a decade before Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963), “The Lottery” depicts a world in which women, clad in “faded house dresses,” are defined solely by their families. Franklin writes:

Though “The Lottery” has an anachronistic quality, with an atmosphere at once timeless and archaic, in fact it describes the world in which Jackson lived, the world of American women in the late 1940s, who were controlled by men in myriad ways large and small: financial, professional, sexual.

According to Franklin, Jackson had told a friend that the story “had to do with anti-Semitism”; its theme is “strikingly consonant” with the French Holocaust survivor David Rousset’s L’Univers concentrationnaire (1946), “which argues that the concentration camps were organized according to a carefully planned system that relied on the willingness of prisoners to harm each other.” “The Lottery” more obviously drew upon Jackson’s discomfort with living among her neighbors in North Bennington, Vermont, as the wife of a high-profile New York Jewish intellectual who behaved most unconventionally herself.

But it was years later, after a much-publicized feud with the teacher of her third-grade daughter, that Jackson and her family were subjected to verbal harassment and vandalism in Bennington, including “even swastikas soaped on the windows”—painful material to be tilled into the rich soil of We Have Always Lived in the Castle. In his preface to The Magic of Shirley Jackson (1966), her husband, Stanley Edgar Hyman, remarked that Jackson “was always proud that the Union of South Africa banned ‘The Lottery,’ and she felt that they at least understood the story.”

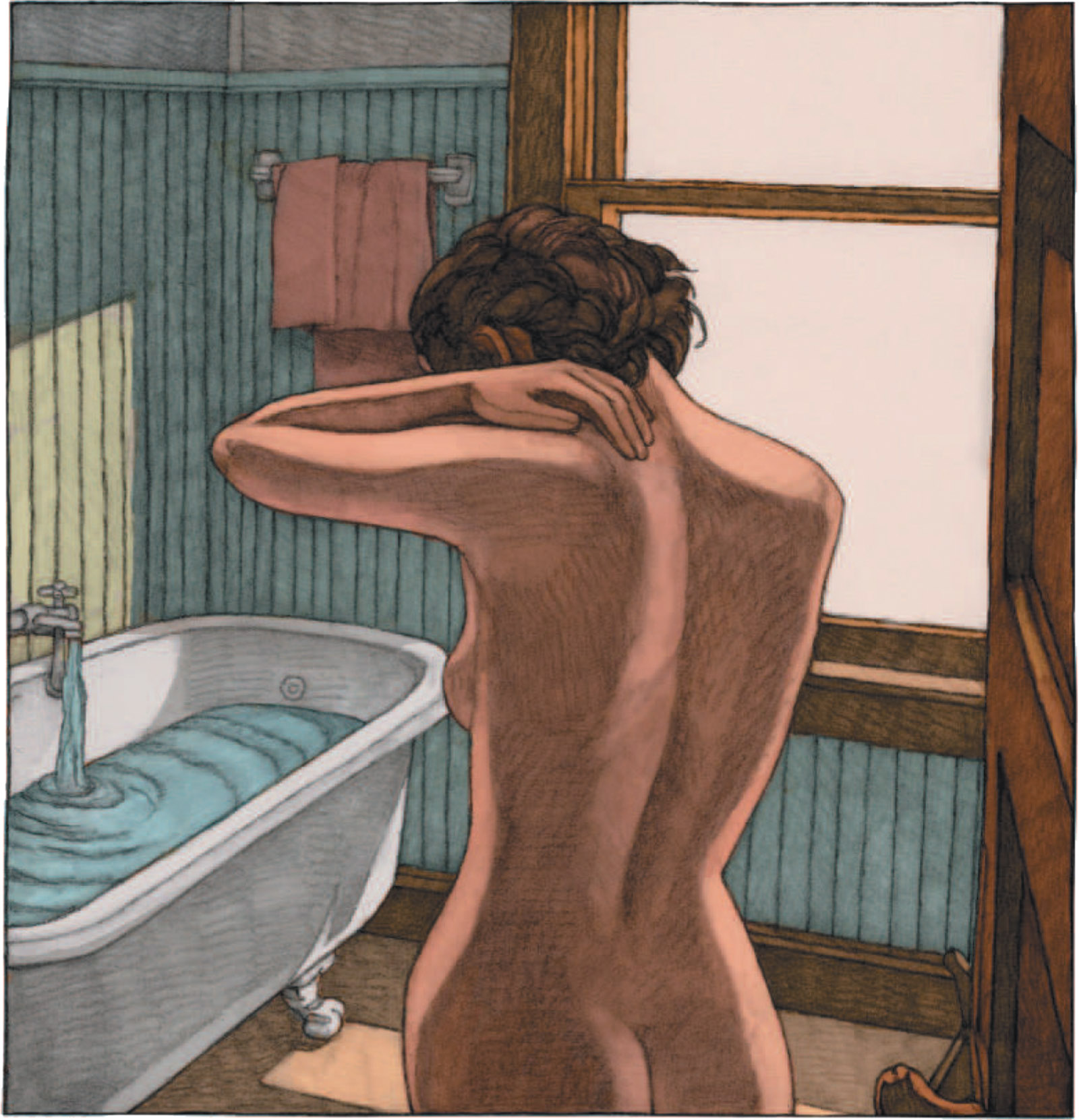

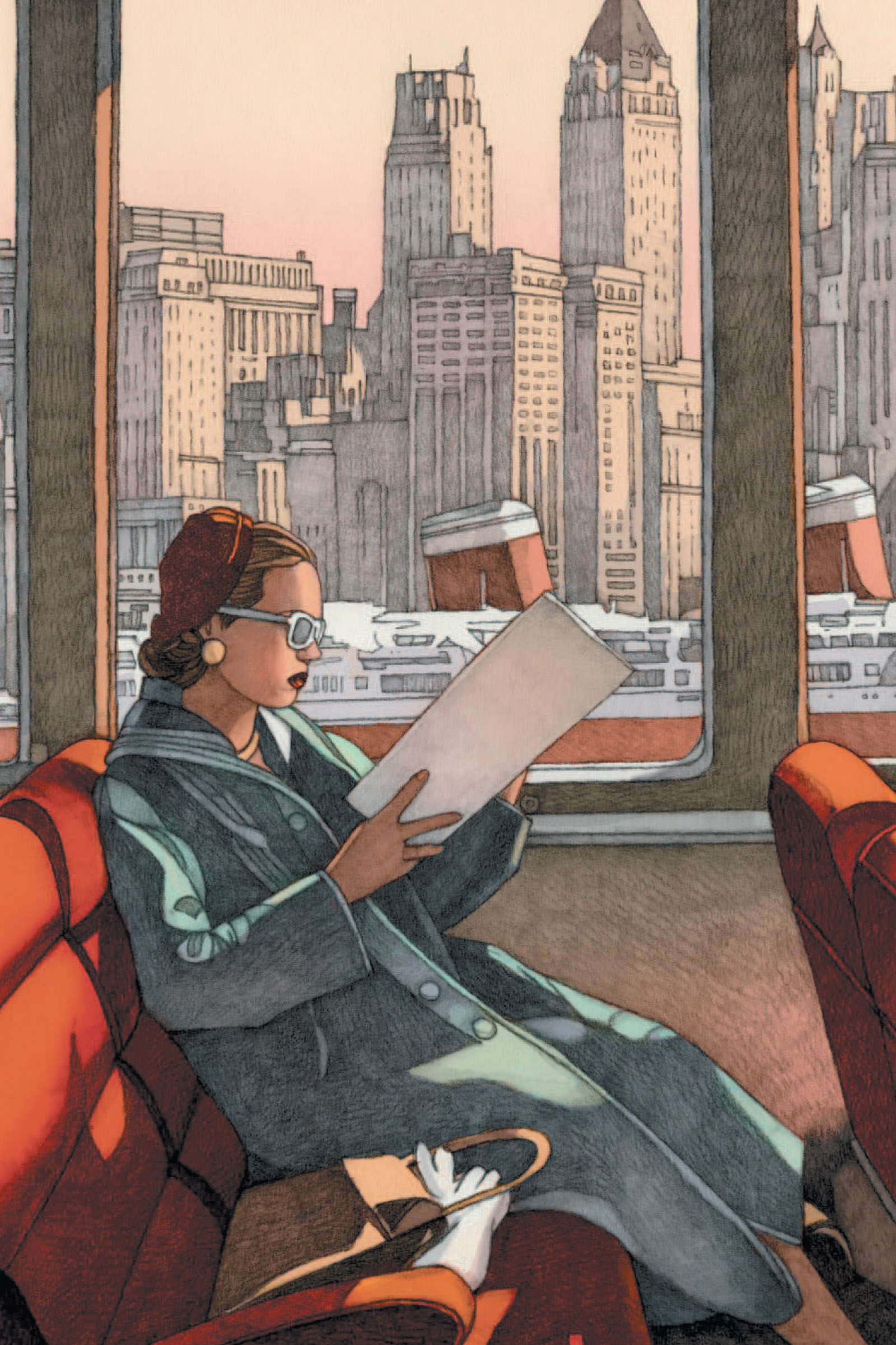

Nearly seventy years after the first publication of “The Lottery,” Jackson’s grandson Miles Hyman has created a “graphic adaptation” in dreamlike slow motion, expanding the story’s eleven condensed pages to 160. Hyman’s colors are subdued, muted, and otherworldly, as if we are gazing into the past; as action intensifies all colors shift to sepia, but a harsh and charmless sepia, as in a particularly dour comic strip of another era. Hyman’s most inspired, or audacious, idea is to provide background for the action of June 27 in a prequel dramatizing the evening of June 26 when the grim-faced town elders responsible for the lottery meet to prepare ballots for the drawing, and a tenderly erotic visualization of Tessie Hutchinson on the morning of her death, disrobing, gazing at herself in a mirror, and bathing—for the final time (see illustration on page 47). In an astonishing act of sympathy, Hyman presents Tessie Hutchinson as intensely female; it is perhaps only when the victim-to-be is naked and alone that she acquires a singular identity, if only to surrender it soon. The final illustration depicts the town without any people at all—not a scene in Jackson’s story, but hauntingly effective here.

Shirley Jackson was born on December 14, 1916, in San Francisco, of well-to-do and socially ambitious parents. She would die at the age of forty-eight, of “heart failure” in her sleep, on August 8, 1965, in North Bennington, survived by her husband (to whom she was married in 1940; he would outlive her by five years) and four young children (Laurence, Joanne, Sarah, Barry).

Through her adult life Jackson managed, while maintaining a legendarily gregarious and intellectually intense household, to publish six novels, of which two (The Haunting of Hill House, We Have Always Lived in the Castle) are classics of American gothic fiction; a collection of unnervingly original, thematically linked stories, The Lottery: The Adventures of James Harris; and warmly humorous, best-selling memoirs of family life titled Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons, for which, in many quarters, she was best known. Inevitably, much has been made of this seeming bifurcation in Jackson’s work; obituaries expressed naive wonder that the “motherly-looking” woman of the family memoirs could write “chillingly horrifying” short fiction. As Hyman wryly notes, “This seems to me to be the most elementary misunderstanding of what a writer is and how a writer works, on the order of expecting Herman Melville to be a big white whale.”

Advertisement

Jackson was a naturally gifted short-story writer for whom the form was a continuous challenge and delight. Her first story, “Janice,” published in a Syracuse University literary magazine in 1938 when she was a freshman, is nearly as accomplished, for all its brevity, as her more mature work; when her future husband, a fellow undergraduate at Syracuse, read “Janice” he demanded to know who the author was and vowed that he would marry her, which he did within two years. Through her career Jackson’s stories appeared in remarkably diverse magazines—The New Yorker, Ladies’ Home Journal, Vogue, Good Housekeeping, Mademoiselle, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction—and were frequently anthologized in The Best American Short Stories and The O. Henry Prize Stories, at that time widely read and reviewed. Though Hyman complained that Jackson “received no awards or prizes, grants or fellowships” and was routinely left off lists of distinguished writers, the inclusion in these volumes constituted a substantial literary honor, and The Haunting of Hill House was nominated for a National Book Award in 1960.

Following Jackson’s premature death, both her published and unpublished work has appeared in a succession of volumes, among them The Magic of Shirley Jackson (The Bird’s Nest, Life Among the Savages, Raising Demons, eleven short stories), selected by Stanley Edgar Hyman, and the Library of America volume Shirley Jackson: Novels and Stories, which I edited. Apart from numerous critical studies of her work there have been two excellent biographies: Judy Oppenheimer’s Private Demons: The Life of Shirley Jackson* and now Ruth Franklin’s Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, which builds upon Oppenheimer’s pioneering work with new material provided by Laurence Hyman, a cache of sixty recently discovered pages of correspondence between Jackson and a female reader, and extensive interviews.

As the subtitles of Jackson’s biographies echo each other—demons, haunted—so both biographies present a near-identical portrait of her as daughter, wife, mother, writer: these roles inextricably knotted together through Jackson’s adult life, often to the point of near-unbearable pressure and stress. Jackson’s patrician, socially conscious, and woundingly censorious mother, Geraldine Bugbee, was the great-great-granddaughter of a wealthy San Francisco architect; clearly the model for the nightmare mother-figures in Jackson’s fiction, particularly the embittered invalid-mother of Hill House, Geraldine persisted in criticizing and belittling Jackson long after she had acquired national renown as a writer. In Franklin’s words, Jackson’s mother had “never loved her unconditionally—if at all”; Oppenheimer’s biography begins with the equally blunt statement: “She was not the daughter her mother wanted.” On the occasion of the success of We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Geraldine had no congratulations for her daughter but could only complain about Jackson’s picture in Time:

Why do you allow the magazines to print such awful pictures of you…for your children’s sake—and your husband’s…. I have been so sad all morning about what you have allowed yourself to look like…. You were and I guess still are a very wilful child….

Jackson was forty-six at the time.

Even as Jackson continued to appeal to her parents for approval, much in her behavior seems to have been in defiant reaction to them and what she perceived as the numbing conformity of their lives. Her early novels—The Road Through the Wall, Hangsaman, and The Sundial—contain satiric portraits of superficial, hypocritical adults; The Bird’s Nest (1954) dramatizes, before the popular film The Three Faces of Eve (1957), the splitting of the psyche of a sensitive young woman into several personalities, in reaction to the stultifying role to which she is expected to submit.

In a note to herself written at the time of the composition of this novel Jackson remarks: “i am tangling with things in [The Bird’s Nest] which are potentially explosive (and thus things in myself potentially explosive).” Franklin observes:

Many of [Jackson’s] books include acts of matricide, either unconscious or deliberate…. Killing off Geraldine’s fictional counterparts was the only way [Jackson] could silence that disapproving voice.

Both the Hymans were obsessive book collectors, eventually amassing an estimated 100,000 books. In their sprawling and eclectic library were hundreds of books on witchcraft, the occult, and spiritualism, a particular interest of Jackson’s that may have begun as intellectual curiosity but became a prevailing fascination and another way of defying the feminine orthodoxy her mother represented. Though Jackson claimed to be embarrassed by being aligned with witchcraft, she seems to have found meaning in it; as her mental health weakened, she became genuinely preoccupied with “omens and signs.” Franklin notes:

The witchcraft chronicles [Jackson] treasured—written by male historians, often men of the church, who sought to demonstrate that witches presented a serious threat to Christian morality—are stories of powerful women: women who defy social norms, women who get what they desire, women who can channel the power of the devil himself.

Jackson’s last completed novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, is a first-person narrative in which adolescent witchcraft is celebrated; Merricat is an unrepentant murderess, with canny ways of survival in the midst of enemies that mimic Jackson’s own.

In an informal talk on writing (“Experience and Fiction,” in the posthumously collected Come Along with Me), Jackson remarks passionately:

i like writing fiction better than anything, because just being a writer of fiction gives you an absolutely unassailable protection against reality; nothing is ever seen clearly or starkly, but always through a thin veil of words.

Of famous literary marriages, not a few seem to have been forged in hell. Yet like the marriages of Jean Stafford and Robert Lowell or Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, the marriage of Shirley Jackson and Stanley Edgar Hyman was both fruitful and destructive (to the wife); the passionately conflicted marital life seems to have been a stimulant to both, an inspiration as well as a font of rage and exhaustion. Out of the wellsprings of domestic life—its pleasures, its miseries, its repetitions—came much of the imagery of Jackson’s fiction, the painful as well as the light-hearted. Virtually all of her discomforting tales are set purposefully in houses, as places of definition and confinement. Here in her essay “Memory and Delusion”—included in the recent anthology Let Me Tell You, coedited by two of her children, Laurence Jackson Hyman and Sarah Hyman DeWitt—is the captive cheerily assuring strangers that all is well:

I am a writer who, due to a series of innocent and ignorant faults of judgment, finds herself with a family of four children and a husband, an eighteen-room house and no help, and two Great Danes and four cats…. It’s a wonder I get even four hours’ sleep, it really is.

Lest one think that the housewife-mother is complaining, here is the assurance:

All the time that I am making beds and doing dishes and driving to town for dancing shoes, I am telling myself stories. Stories about anything, anything at all. Just stories.

That the plea is pitched in a comic and resolutely nonshrill voice should not distract from the writer’s cri de coeur.

It is not surprising that Jackson’s “housewife persona” (as Franklin calls it) came to take up so much of her mental energy, for the

idea of the house—what is required to make and keep a home, and what it means when a home is destroyed—is important in just about all of Jackson’s novels.

The compulsiveness to write of housekeeping, especially its frustrations and failures, is bound up with the author’s wish “metaphorically to put things away—anxieties, fears, all the messes of life—and her corresponding inability to do so.”

In “Here I Am, Washing Dishes Again,” a seemingly lighthearted memoir takes on surreal overtones of threat and unease in which kitchen utensils and gadgets assume “personalities”—always safely reined in by Jackson’s resolute comic voice, so that the reader will not be alarmed and mistake the author for a feminist protesting her fate as a housewife trapped in a kitchen. (Jackson, like other gifted women writers of her time, among them Jean Stafford and Flannery O’Connor, had little sympathy for feminism, which would have seemed to her a demeaning sort of conformity; she knew herself unique.)

The virtually unknown, ingeniously constructed story “Showdown”—also included in Let Me Tell You—immerses its hapless protagonist in a “haunted” place in which he is doomed to relive the same violent incident again and again—seemingly forever: here is repetition as madness, confinement. The Haunting of Hill House gathers all the author’s strengths, Franklin writes, in its evocation of

a house that contains nightmares and makes them manifest, in which fantasies of homecoming end in eternal solitude…the ultimate metaphor for the Hymans’ symbiotic, tormented, yet intensely committed marriage.

Though Stanley Edgar Hyman was her exacting first reader and most enthusiastic supporter, Jackson nonetheless did all the housework and child care, just as she cheerily tell us; for a while husband and wife even shared a single typewriter, which Hyman “commandeered.” As a young child their son Laurie defined “Daddy” as “man who sits in chair reading.” But when Daddy was not at home, reading or typing or hosting boisterous parties, he was a very popular professor at Bennington College, trailing admiring girl undergraduates in his wake, a source of perennial hurt, rage, and depression for the writer-wife who could take only a feeble sort of revenge by writing such stories as “Still Life With Teapot and Students” and creating, in her humorous work, a portrait of Daddy as a bumbling, hapless, foolish, and emasculated figure. It did not help the Hymans’ strained relationship that after thirteen years of toil on his second book, The Tangled Bank: Darwin, Marx, Frazier and Freud as Imaginative Writers (1962), Hyman met with disappointing reviews and modest sales while Jackson’s work continued to prosper.

Yet Jackson seems to have been desperately in love with Hyman, while also seeming to have bitterly resented him. The fantasies of the final, tormented years of her life had to do with flight, starting a new life, even as she remained mired in the responsibilities of her household and the humiliations of her marriage. In a rambling accusatory letter to Hyman (probably written in 1958, as Franklin notes, while Jackson was immersed in Hill House) she speaks of her

loneliness in the face of his indifference to her and the children, his inveterate interest in other women, his belittling her, his obsessive devotion to teaching and to his students, female all, “which leaves no room for other emotional involvements, not even a legitimate one at home.”

The letter concludes plaintively:

you once wrote me a letter (i know you hate my remembering these things) telling me that i would never be lonely again. i think that was the first, the most dreadful, lie you ever told me.

Hyman’s treatment of Jackson exhausted her and pushed her into depression, nervous collapse, and a pathological addiction to drugs as well as alcohol and food that surely shortened her life. Friends of the couple professed amazement at Hyman’s disregard for the connection between his profligate behavior and Jackson’s mental health. It was not clear to observers

whether Hyman failed to understand how hurtful his actions were to Jackson or whether he simply did not care. What is clear is that the flourishing of his teaching [and his romantic relationships with his Bennington students] corresponded with a steep decline in [Jackson’s] mental equilibrium.

Hyman was jealous of Jackson earning more money than he did, even as he goaded her into writing for money and called her “lazy” when she couldn’t write; she complained to a friend that he’d told her to “get the hell up to that typewriter and write something or your fingers will fall off.” Perhaps not physical abuse but verbal abuse seems to have caused Jackson, for all her intelligence and wry good humor, to internalize her husband’s demands: “i feel i am cheating Stanley because i should be writing stories for money.” Her solace was diary-writing, kept secret from the bullying husband who would have considered it a “criminal” waste of time.

Jackson confides in her diary what she could confide in no one else; she must wrest control of her life back from her husband, somehow: “insecure, uncontrolled, i wrote of neuroses and fear and i think all my books laid end to end would be one long documentation of anxiety.” Only in the whimsy of Jackson’s final, uncompleted novel, Come Along with Me, written in the mode of one of Anne Tyler’s lighter novels, is this impulse toward flight realized without nightmare consequences on the part of a wife with witch-like powers; significantly, the novel’s opening line is “I always believe in eating when I can.”

Unable to leave her husband, as she seems to have been unable to break off relations with her mother, Jackson took revenge on them both, in effect, by making herself as “unfeminine” as possible. Oppenheimer’s portrait of Jackson is vivid and memorable, in the recollections of her children Laurence and Sally:

Seen in a room full of slim, impeccably groomed faculty wives, [Jackson] almost seemed to represent another species altogether. She was fat, she wore no makeup, and her hair, by now a colorless light brown, was held straight back from her face with a rubber band. The face itself, with its square jaw and heavy jowls, was severe, almost masculine in its lines…. It was an arresting face,…but it was not a pretty one, and patently not that of the average mother.

Both biographers note Jackson’s addiction to powerful, potentially lethal psychotropic drugs, prescribed to her by doctors seemingly oblivious to their danger, and unconcerned that she was drinking heavily as well. Dexamyl, Miltown, Valium, Seconal—“eventually the antipsychotic Thorazine, which may have exacerbated Shirley’s anxiety rather than alleviating it. The drugs were believed to be safe,” Franklin writes. It is not surprising that Jackson began to disintegrate mentally in her forties; she suffered from myriad ailments including panic attacks and agoraphobia, a terror of leaving the house, all of which she confronted bravely, yet without apparently cutting back on medication, alcohol, and food. Nor did Hyman, a heavy drinker himself and “corpulent,” seem concerned for Jackson’s health.

On August 8, 1965, Jackson lay down for a “customary nap” after lunch, and could not be roused by her family. In Oppenheimer’s account it is Sally who discovers her mother upstairs in bed; she summons Stanley, who hurries upstairs. Astonishingly, it is noted that two weeks before, Sally had “tried to commit suicide, taking all the tranquilizers she could find in the house, then lying down with a copy of Hill House open in front of her.” Her parents had rushed her to the hospital to have her stomach pumped but the incident had not seemed to arouse much alarm in the household; Jackson wrote of it casually to Sally’s older sister Joanne, indicating that she “had not taken it very seriously, it was just one more of Sally’s dramatic gestures.” In the light of this “attempted suicide” Jackson’s condition had not seemed, at first, to be alarming:

When Sally and Stanley saw Shirley lying still and unresponsive on the bed, their first thought was that she might be playing a strange game of revenge. “We assumed she had taken a bunch of pills to get even with me,” Sally said. “We used to do that kind of mother-daughter stuff.”

However, Jackson’s heart had ceased beating; the cause of death would be attributed to “arterial sclerotic heart disease.” In fact there was no autopsy, and the local North Bennington doctor acknowledged that he had no reason other than his own “moral certainty” to make this diagnosis. “It’s a very common cause of sudden death. I don’t think there was any particular cause—she went to bed and went to sleep and this thing happened. I no longer have the files.”

Franklin’s version is briefer, without Oppenheimer’s amazing narrative that the father and daughter had initially supposed that Jackson had deliberately taken an overdose of drugs. Here, it is Hyman who fails to rouse Jackson, and Sarah (Sally) is summoned to help. No one in the Hyman household or elsewhere seems to have been overly concerned about the exact cause of Jackson’s death, nor does either biographer raise the possibility that she died as a consequence of drug overdose: deliberate, accidental?

In the Bennington medical hinterland far from a research hospital or reputable medical center, there was not likely to be an autopsy even for such an abrupt and unexpected death—the “official cause was a coronary occlusion due to arteriosclerosis, with hypertensive cardiovascular disease as a contributing factor.” But this “official” diagnosis was sheer speculation at the time, if not shameless medical expediency.

In her last diary, written at a time of psychological distress when she was unable to write fiction, Jackson spoke of the guilty secrecy of such writing. Yet the diary seems to have been cathartic for her, or at least heartening, as Jackson speculates on the possibility of making a break for freedom and the great solace of writing itself:

i think about the glorious world of the future. think about me think about me think about me. not to be uncontrolled, not to control. alone. safe…to be separate, to be alone, to stand and walk alone, not to be different and weak and helpless and degraded…and shut out. not shut out, shutting out…on the other side somewhere there is a country, perhaps the glorious country of well-dom, perhaps a country of a story. perhaps both, for a happy book…laughter is possible laughter is possible laughter is possible.

This Issue

October 27, 2016

Panama: The Hidden Trillions

John Cage’s Gift to Us

-

*

G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1988. ↩