Considering the European Union’s unhappy history with national referenda, there was no guarantee that Brexit would mean Brexit, to adapt the slogan adopted by Britain’s prime minister, Theresa May. True, the British people voted to leave the EU by a count of 52–48 percent on June 23, 2016. But the people of several other EU member states had, over the years, similarly voted to show Brussels a collective middle finger and they had been ignored. There were plenty of skeptics who assumed that the ever-resourceful mandarins and panjandrums of the Continent would find a way to ensure that the Brexit vote would suffer the same fate.

These doubters could cite ample precedent. In 2008 Irish voters refused to ratify the Lisbon Treaty codifying (some would say expanding) the EU’s powers, with 53 percent voting no. The treaty needed the approval of all member states to come into force, so Brussels put the squeeze on the Irish—and sure enough, they voted again the following year, this time delivering the right result. As it happened, the same sequence—rejection, followed by a change of heart—had played out in Ireland over the 2001 Nice Treaty (and in Denmark over the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which formally upgraded the earlier European Economic Community into today’s EU). Indeed, the Lisbon accord only arose after the EU tried and failed to adopt for itself a written constitution, along with a flag, anthem, and dedicated “Europe Day.” Voters in both France and Holland said no to that in referenda in 2005. Rather than drop the constitution, Brussels repackaged it as the treaty signed in the Portuguese capital. The EU has a habit of refusing to take no for an answer.

So it was plausible to think that Britain might not leave the twenty-eight-member club after all, despite what its people had said in the Brexit vote. One imagined outcome involved the British government delaying, engaging in endless prenegotiations with the EU, or waiting until the national elections in France this spring and Germany this autumn were out of the way, rather than triggering Article 50—the section of the Lisbon Treaty that allows for the withdrawal of a member state (a situation that has never arisen before). Another version envisaged Britain formally leaving the EU, but keeping its place in the part that matters most: the European single market, which allows goods to be traded as easily between Manchester and Munich as between London and Liverpool. After all, no Briton voted to leave the single market: that wasn’t on the ballot.

But the British prime minister did not attempt either of these approaches. On March 29, Theresa May dispatched a diplomat to play the role of mailman and hand to Donald Tusk, the president of the European Council, a six-page letter invoking Article 50 and thereby giving notice that Britain will leave the EU at the stroke of midnight on March 29, 2019. In a careful bit of choreography, May stood up in the House of Commons at the same time and declared, “This is an historic moment from which there can be no turning back.”

May sought an emollient tone, in person and in writing, praising the EU for its “liberal, democratic values,” its advocacy of free trade, and its necessity for global security. But there was no disguising the choice she had made. She has eschewed the option of a “soft” Brexit, which would attempt to preserve much of Britain’s existing economic, diplomatic, cultural, and social relationships with Brussels, preferring an ultra-hard version—one that will take the UK out of both the single market and the much broader European customs union, a rupture so severe that, before 2016, even the most unbending anti-EU campaigners rarely called for it. In two years’ time, Britain is set to trade with its closest neighbors on terms usually applied to those from opposite corners of the globe. Britons probably never saw continental Europeans as family—that was part of the problem—but soon they will be relating to them as strangers.

How did this happen? How did May, who campaigned, albeit in lukewarm fashion, for the Remain side in last summer’s referendum, end up pushing for such a hard-core version of Leave?

Any explanation has to begin with the parlous state of the official opposition to the Conservatives now in power. In its postwar history, the Labour Party has rarely been weaker. Led by Jeremy Corbyn, the veteran leftist backbencher and maverick propelled into the top job by a grassroots rebellion against the party establishment in 2015, Labour has mounted only the most feeble parliamentary resistance to Brexit. Some blame Corbyn himself for that, recalling that for decades he opposed the EU on socialist grounds, deeming it a capitalist club. They suspect he is still a Leaver in his heart. Like May, he was only a tepid campaigner for staying in the union last spring.

Advertisement

But the problem goes beyond Corbyn. Labour is paralyzed by Brexit. Most of its MPs, members, and activists are ardent Remainers, but the referendum revealed that a good proportion of Labour voters were Brexiteers—enough of them to swing the overall result. Many were white working-class voters in postindustrial towns such as Stoke, Doncaster, or Ebbw Vale, places left behind by globalization and automation. They were British forerunners of the rust belt Democrats who voted to put Donald Trump in the White House five months later. Their support for Brexit shook the Labour leadership, prompting the fear that any defiance of the referendum verdict could see onetime Labour loyalists defecting to the anti-EU, populist UK Independence Party, previously led by Trump pal Nigel Farage. And so Labour said its duty was to defer to the popular will.

The decisive moment came in February, when May came to the House of Commons after the Supreme Court had ruled that she needed parliamentary permission to trigger Article 50. Labour proposed a series of amendments but when those were defeated it faced the stark choice of thwarting Brexit or backing it. After just a few days of Commons debate, and to the shock of many devoted Labourites, Corbyn imposed the discipline of a parliamentary whip as he led his MPs to vote with May and her Conservative government. Fifty-two Labour MPs rebelled, but the rest voted to leave the EU.

Had Labour resisted, it could have made allies across the House. Take Scotland. The 2014 referendum on Scottish independence was soundly defeated after Scots concluded that, aside from any sentimental attachment they felt toward the United Kingdom, the economic risks of separation were too great. But the Scottish National Party, which holds fifty-six of Scotland’s fifty-nine seats in the British Parliament, is so avowedly pro-EU—no surprise given that 62 percent of Scots voted to remain—that at the end of March it took the triggering of Article 50 as the cue to demand that Prime Minister May stage a second independence referendum. Though the polls have not moved much since 2014, the SNP calculates that its position will get stronger as Brexit unfolds.

Led by Nicola Sturgeon, the steely first minister of Scotland, the SNP believes that, faced with a choice, Scots will prefer a breakaway from the United Kingdom to being “dragged out of Europe against our will,” as the party puts it. Sturgeon’s central demand is continued Scottish membership in the European single market. Initially, she pressed May to seek from Brussels a special arrangement that might allow for that, even as the wider UK leaves the EU. May rebuffed that request, allowing Sturgeon to say that only independence will make single-market membership possible. (An independent Scotland might go further, seeking to remain inside the EU itself, but that idea is legally knotty: for one thing, Madrid is wary of setting any precedent that would encourage Catalan separatism and could wield its veto to block the Scots. Single-market membership is the easier ask.)

The crucial point is that there was a solid Scottish bloc in Parliament ready to vote for a soft Brexit that would have kept the UK in the single market. There are perhaps twenty Europhile Tories who might have rallied to that flag. Since the Conservative majority in the House of Commons is tiny—about a dozen—had Labour joined the rebels’ ranks that would have been enough to push May toward the mildest of Brexits. But once Labour folded, any effort at opposition was doomed.

Still, if a soft Brexit exerted little pull on May, the tug toward a hard Brexit has been powerful. Part of it comes from May’s own government experience. Before she became prime minister, the issue that defined her in the public mind was immigration. In her previous position as home secretary, she toiled hard to reduce the number of newcomers to Britain, driving through an immigration act whose purpose was, as she put it, “to create a hostile environment” for illegal immigrants, including asking landlords to inspect the documents of all prospective tenants. Notoriously she sent billboard trucks into areas with large immigrant communities, with posters bearing the simple slogan: Go Home or Face Arrest. She, like many others, concluded that the Leave vote was, at root, a protest against immigration and that therefore the only viable Brexit was one that gave the British government greater control over its borders.

By contrast, British membership in the single market meant accepting the EU’s four freedoms—freedom of goods, capital, services, and, crucially, people. Continuing to embrace that last freedom, which had facilitated the arrival of an estimated 1.5 million newcomers to Britain since 2004, mainly from Eastern Europe, was a red line that, May concluded, the electorate would not let her cross. If ending the free movement of EU citizens into Britain meant leaving the single market, so be it. (Plenty of pro-EU types regret that May didn’t at least test her European counterparts on this. With a referendum behind her, she’d have had strong leverage to demand the right to impose at least some limits on migration, a temporary “handbrake,” in the jargon. But she never even asked the question.)

Advertisement

What’s more, May’s experience in the Home Office made her equally determined to break free of the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice—and that too meant leaving the single market. Those internal motives have been buttressed daily by the insatiably Europhobic wing of the Conservative Party, whose nostrils are permanently twitching for any scent of betrayal. They were ready to pounce on anything less than a self-harmingly masochistic version of Brexit. And reinforcing them, of course, is the conservative British press. The Daily Mail, The Daily Telegraph, the Daily Express, and the Sun have been agitating against the EU for nearly three decades: they want a total and clean break. The photograph on the front page of the Sun on the day Article 50 was invoked showed a slogan projected onto the white cliffs that look out from the English port closest to France: Dover and Out.

Remainers are, naturally, in mourning, as they have been since June 23. They are for the most part younger, urban, and more educated voters, represented by the tiny pro-European Liberal Democrats and Greens, and more vocally by heavyweight rebels in both the Tory and Labour parties, including former prime ministers John Major and Tony Blair, with backing from big-name liberal columnists on the Op-Ed pages. These voters see Britain spurning its nearest neighbors and joining instead the nativist, populist wave that carried Trump to the White House and threatens to make Marine Le Pen the next French president. They worry that Brexit will unravel the UK itself, with Scotland succeeding in breaking away, while the delicate peace that has held in Northern Ireland is imperiled. Since the Republic of Ireland is an EU member, they fear that Britain’s departure inevitably requires the resurrection of the hard border that once separated Northern Ireland from the Republic—a border that will soon mark the boundary between the UK and the EU. Memories of that frontier, and the conflict and terrorism associated with the so-called Troubles, have made Ireland especially anxious about Brexit. No European economy is more closely entwined with the UK: for the Irish, undoing those bonds is a daunting prospect.

But it’s not all emotion. Remainers see gaping holes of logic in the government’s case. Despite their hard line, May and her ministers say they want frictionless free trade with Europe, on the best possible terms. They want continued close security cooperation. They want Europe to be a model of free trade in a world turning to protectionism. They want Britain to be a global magnet, attracting people of ambition. To which Remainers say: well, that’s exactly what you had, until you decided to throw it all away.

Most of the British commentary on Brexit has been parochial, assessing the effect of this decision on the UK. Less discussed are the consequences for Europe. UK participation in the grand European projet was always fraught: the UK joined late, its membership long vetoed by Charles de Gaulle. But once in, the British lent enormous weight to the venture. The Dutch diplomat Max Kohnstamm, present at the creation, longed for the presence of the more freewheeling, liberal British as a counterweight to “Teutonic coherence” and “Gallic uniformity.” Along with France, the UK was the only EU member with hard military power.

Now that will be gone. Tellingly, May’s letter to European Council President Tusk implicitly threatened to withhold UK defense cooperation if she didn’t get the favorable trading terms she sought—a demand one London tabloid distilled in a headline: “Your Money or Your Lives.” The deeper European fear is that a structure that has taken a battering in recent years—by the debt-ridden euro, by refugee crises, and by sclerotic economic growth—has now had a crucial supporting plank removed. With Le Pen demanding a Frexit and the Dutch populist Geert Wilders still agitating for a Nexit despite his indifferent performance in elections in March, the body that has helped keep the peace on a continent with a murderous history feels itself to be fragile. All of this was contained in the plaintive four words uttered by Tusk once he had May’s letter in his hand: “We already miss you.”

Tusk, backed by German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other European leaders, has said that the EU’s remaining twenty-seven member states will maintain total unity as they negotiate divorce with the UK. That may not be a hollow boast: the EU has rarely enjoyed the binding force of a common adversary. It has one now. It will want to use Brexit as a demonstration case, pour décourager les autres. It will surely unite in ensuring that the UK pays a high price for its act of secession.

Meanwhile, many Europeans watch events in neighboring countries, nervously checking the opinion polls in France or Germany, trying to gauge the populist fever heating up much of the continent. For years, Euroskeptics said the great flaw of the enterprise was that Europeans did not see themselves as belonging to a single society, sharing a common destiny. They did not, in short, constitute a demos. Yet Brexit, and the movements swelling in its wake, seem to have changed that.

In late March, tens of thousands of British citizens took to the streets of London to “Unite for Europe,” many of them wearing the blue and gold of the EU flag: an unprecedented sight in Britain. Fleet Street has a new publication, The New European, a print paper that started as a four-week pop-up right after the referendum and is still going strong. And stopping Le Pen has become a Europe-wide cause, as was stopping Wilders, uniting liberals in different countries, on social media and elsewhere, who previously had little connection. Brexit might inflict grave damage on the UK and might even wreck the EU. But it might also bind Europe and Europeans closer together than ever.

—April 12, 2017

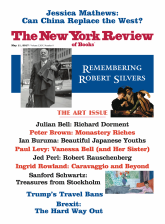

This Issue

May 11, 2017

The Virtuoso of Compassion

Trump’s Travel Bans