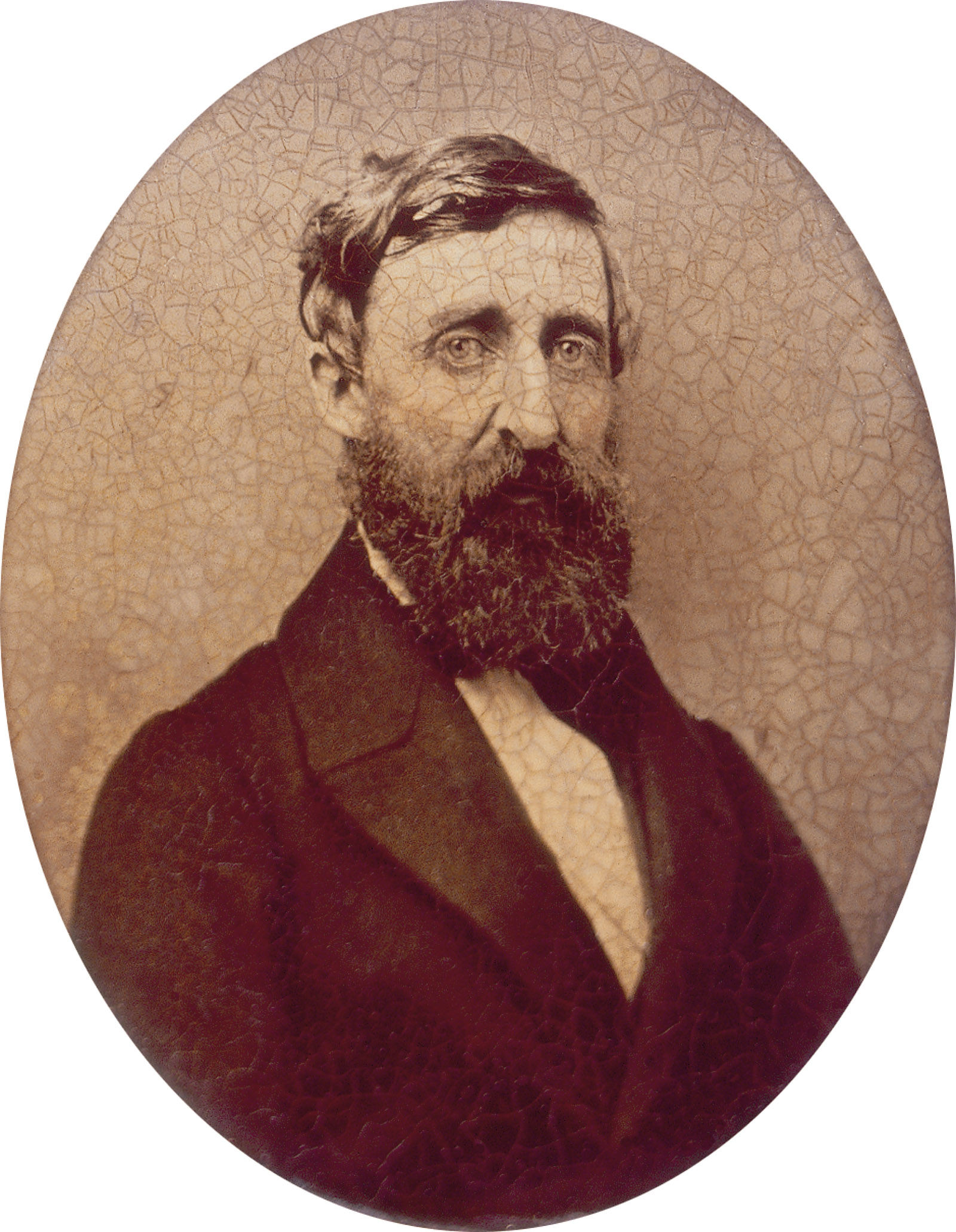

This year America celebrates the bicentennial birthday of Henry David Thoreau with many excellent publications about his life, legacy, and love of the natural world. Only his fellow citizens are likely to lend an ear to them. Unlike his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thoreau hardly makes it onto the list of notable American authors outside his home country. His peculiar brand of American nativism has little international appeal, for as Emerson wrote in his funeral eulogy of May 9, 1862:

No truer American existed than Thoreau. His preference of his country and condition was genuine, and his aversation from English and European manners and tastes almost reached contempt.

These days the question of what it means to be a “true” American resists rational analysis. Whatever one can say about Americans that is true, the opposite is equally true. We are the most godless and most religious, the most puritanical and most libertine, the most charitable and most heartless of societies. We espouse the maxim “that government is best which governs least,” yet look to government to address our every problem. Our environmental conscientiousness is outmatched only by our environmental recklessness. We are outlaws obsessed by the rule of law, individualists devoted to communitarian values, a nation of fat people with anorexic standards of beauty. The only things we love more than nature’s wilderness are our cars, malls, and digital technology. The paradoxes of the American psyche go back at least as far as our Declaration of Independence, in which slave owners proclaimed that all men are endowed by their creator with an unalienable right to liberty.

In this sense Thoreau was truly American. In her splendid new biography, Henry David Thoreau: A Life, Laura Dassow Walls, a professor of English literature at the University of Notre Dame, offers a multifaceted view of the many contradictions of his personality.

Thoreau has come “down to us in ice, chilled into a misanthrope, prickly with spines, isolated as a hermit and nag,” she writes, acknowledging that he did his fair share to earn that reputation. He was prickly enough that their friend Elizabeth Hoar confided to Emerson, “I love Henry, but do not like him; and as for taking his arm, I should as soon take the arm of an elm tree.” From early on people accused him of hypocrisy, censuring him for championing self-sufficiency while he occasionally returned home for dinner during the years he lived at Walden Pond. (“No other male American writer has been so discredited for enjoying a meal with loved ones or for not doing his own laundry,” writes Walls.)1

Walls does not deny that Thoreau was “occasionally hermitous, and even a nag,” yet in her full-bodied portrait he comes alive also as “a loving son, a devoted friend, a lively and charismatic presence who filled the room, laughed and danced, sang and teased and wept.” The citizens of Concord loved him dearly because, in addition to being nettlesome, he was genuine and kind.

In a finely tuned discussion of his ambivalent sexuality—one that avoids excessive speculation without avoiding the topic altogether, as many scholars tend to do—Walls concludes that Thoreau, who probably died a virgin, was drawn to men and women equally. With Aristophanic flair, he noted in his journal: “I love men with the same distinction that I love woman—as if my friend were of some third sex.”

Thoreau’s friendship with Margaret Fuller—editor of the Transcendentalist journal The Dial—reveals the extent to which he was free of resentment, vanity, or sexism. In 1840, when he submitted an ambitious essay and a poem to The Dial, Fuller sent him a rejection letter that would have unhinged most other nineteenth-century American men with a Harvard degree, saying of the essay that its thoughts were “so out of their natural order, that I cannot read it through without pain…but seem to hear the grating of tools on the mosaic.” As for the poem, she objected to its “want of fluent music,” comparing it to a “bare hill which the warm gales of spring have not visited.” Thoreau took her criticisms to heart and learned from them. They subsequently became good friends.

Was Thoreau egotistical? Surely, yet as Walls writes, “injustice to another made him storm with the passionate and sleepless rage that powered his great writings of political protest”—writings like “Civil Disobedience” and his fiery defense of the abolitionist John Brown.

His protests were not only political. Like Emerson, Thoreau believed that education was democracy’s highest calling. Upon graduating from Harvard in 1837, he was offered a dream job at Concord’s Center Grammar School, with a lofty salary of $500 a year. He made it clear when he accepted the teaching position that he did not believe in flogging students, yet after the deacon insisted that he administer “corporeal chastisement, the corner-stone of a sound education,” Thoreau disciplined some of his students with a ferule (he did not own a cowhide for flogging). He felt so stained by his act of “uncivil obedience” that he went to the deacon that same evening and resigned, ending his career as a public school teacher ten days after it had begun.

Advertisement

If Thoreau was a hermit, he had a strange way of expressing it. In 1842, three years before building his cabin at Walden Pond, he wrote in his journal: “I have no private good—unless it be my peculiar ability to serve the public—this is the only individual property.” By “public” Thoreau meant many things: the human community of Concord where he spent most of his life, rooted like a tree; the surrounding woods, waters, and wildlife that community shared in common; and the country at large. In everything he did and wrote, Thoreau identified himself first and foremost as a citizen, not only of his hometown and the American republic, but of the natural world that provided them with their material foundations.

Walls suggests that Frederick Douglass and the radical abolitionist Wendell Phillips played a decisive part in Thoreau’s decision to build a cabin at Walden and sojourn there for two years and two months. These abolitionists, each in his own way, convinced Thoreau that “a million men are of no importance compared with one man…[who is prepared] to do right.” Like them, Thoreau wanted to stand as a majority of one. “Any man more right than his neighbors constitutes a majority of one already,” he wrote in “Civil Disobedience.”

It was as a citizen of Concord, hence of America, that Thoreau took up residence at Walden on Independence Day 1845.2 He went there not to isolate himself but to situate himself “a mile from any neighbor”—distant enough for independence, yet close enough to remain within earshot. Walden addresses itself to “you…who are said to live in New England,” and its epigraph declares its intention “to wake my neighbors up.”

Wake them up to what? To the fact that America was still waiting to be discovered, that his neighbors had given up prematurely on its promise of freedom, independence, and God’s heaven on earth. The Puritan pilgrims had brought with them to the New World an infinite expectation, only to succumb to disappointment after setting foot on a continent they saw as wild and harsh, not at all the Eden they had hoped for. Thoreau went to Walden to discover for himself whether America—“this new yet unapproachable America,” as Emerson called it—amounted to a false promise, or whether it did indeed contain a paradise that was not only approachable but touchable.

What he found is that “we occupy the heaven of the gods without knowing it.” Paradise exists all around us, in America’s “wildness,” the natural environment of the continent. In the contact between his own body and America’s forests, meadows, lakes, rivers, mountains, and animals, Thoreau discovered what he called “hard matter in its home.” That home was the “hard bottom” or “reality” that we crave. “I stand in awe of my body, this matter to which I am bound,” he wrote in his journal. “Daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,—rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks!… Contact! Contact!”

The tactile transcendence of America’s wildness opens its prospects to those who would wake up to it. One need not travel to sublime mountain ranges or remote wilderness areas to access it. It lies before us, in what Thoreau called the day’s dawning. “We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn.” Only such expectation brings forth that heightening of the senses that allows America to appear in its dawning ecstasies; and lest we take the notion of dawn too literally, Thoreau declares: “Morning is when I am awake and there is a dawn in me.”

It is impossible to overstate the importance of anticipation in Thoreau’s philosophy of sense perception and spiritual elevation. In another bicentennial biography, Expect Great Things, Kevin Dann lays great stress on the fact that for Thoreau “anticipation precedes discovery.” Dann’s biography concentrates more on Thoreau’s rich psychic life than on his multidimensional life as friend, family member, Concord citizen, political activist, and writer. Through a sympathetic reading of his journal above all, Dann seeks to gain access to the inward paradise of perception that Thoreau inhabited during the last decade or two of his life.

Dann argues that Thoreau cultivated the “thrilled and expectant mood” (Thoreau’s words) because he believed that we only see what we are prepared to see. According to Thoreau:

Advertisement

Objects are concealed from our view not so much because they are out of the course of our visual ray as because there is no intention of the mind and eye toward them…. There is just as much beauty visible to us in the landscape as we are prepared to appreciate, not a grain more.

Thoreau believed in the shamanistic power of expectation. Dann’s biography in fact gets its title from what it takes to be a doctrinal statement that Thoreau recorded in his journal: “In the long run, we find what we expect. We shall be fortunate then if we expect great things.”

Yet it is not enough merely to expect. To deepen and expand the horizon of perception, one must acquire an exacting empirical knowledge of the natural world in its endless particularities, for the intention of the eye follows the intention of the mind. That is why, after graduating from Harvard, Thoreau spent a great deal of time studying the geology and ecology of New England, reading as many accounts as he could of its native species, whether by contemporaries or earlier generations of American naturalists, botanists, farmers, and explorers. In time he became a first-rate naturalist himself, adding his own discoveries to the archival record.

Thoreau’s Animals, edited and introduced by Geoff Wisner, offers an engaging and often entertaining selection of Thoreau’s writings about the wild and domestic animal species he came upon in the forests, farms, and wetlands in and around Concord. It is a companion volume to Thoreau’s Wildflowers, and together the two volumes throw into relief the degree to which Thoreau was almost superhumanly awake to the flora and fauna of his surrounding environment. There is more here than testimony of Thoreau’s much-vaunted “powers of observation.” The volumes offer clear evidence that in his later adult life Thoreau had thoroughly cleansed the doors of perception, and that the world appeared to him as infinite in its local manifestations.

The same holds true for the enchanting book Thoreau and the Language of Trees, by Richard Higgins. In lucid and elegant prose, Higgins traces Thoreau’s deep love affair with various arboreal species, like the white pine of Maine, which, in a formulation that unsettled an editor, he claimed was “as immortal as I am, and perchance will go to as high a heaven, there to tower above me still.” Each of Higgins’s ten chapters contains an essay, followed by pertinent passages from Thoreau. One gets to the end of this book fully persuaded by Higgins’s claim that Thoreau was captivated by trees, and that “they played a significant role in his creativity as a writer, his work as a naturalist, his philosophical thought, and even his inner life.” In a beautiful touch, Higgins adds: “It sometimes seems that he could see the sap flowing beneath their bark.”

Walden—republished by Beacon Press this year with an inspired introduction by Bill McKibben about Thoreau’s relevance to our own spiritually impoverished reality—is arguably the most important work of literary nonfiction in the American canon. Thanks to that book, subtitled “A Life in the Woods,” the image of Thoreau as a lover of woods and trees is entrenched in the American imagination. Yet in The Boatman, Robert M. Thorson reminds us that in the last decade of his life Thoreau devoted a great deal more attention to rivers, especially the three main rivers around Concord (the Sudbury, Assabet, and Concord, known to the seventeenth-century Puritans who settled the valley as the South, North, and Great Rivers). Thorson’s book offers the reader an in-depth account of Thoreau’s lifelong love of boats, his skill as a navigator, his intimate knowledge of the waterways around Concord, and his extensive survey of the Concord River.

“Henry’s unheralded river book is his journal,” writes Thorson. Thoreau’s Journal contains some two million words written over twenty years.3 The Journal is the main focus of an exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum, “This Ever New Self: Thoreau and His Journal,” which brings together nearly one hundred relics of this American saint, including the small green desk on which he wrote most of his life work, the flute with which he enchanted Margaret Fuller and other humans and nonhumans alike, as well as more than twenty of his Journal notebooks, many of his letters, books from his personal library, the only two photographs for which he ever sat, and even some pressed plants from his herbarium. Those many readers and scholars who have increasingly come to consider Thoreau’s Journal his main literary achievement will want to make a pilgrimage this summer to the Morgan.

Both Thorson and Walls make a point of stressing that Thoreau was fully cognizant of what today we call the “anthropocene,” or the era when most of the planet has been touched or altered by human beings. When Thoreau embarked on an excursion to Mount Katahdin in Maine, for example, he imagined he would be venturing into pristine territory, only to find that humans had left their mark in even the state’s most remote regions. In his introduction to Walden, McKibben writes that Thoreau’s expedition “took him through the heart of that then-mighty wilderness,” yet as Walls remarks in a moving passage:

Even where the road ended, the houses did not, and even after the last house, there were logging camps and blacksmith forges, dams and log booms, trails rutted with use, even a billboard. The untouched forest had been logged, each tree cut and branded, its destiny not to reach for the heavens but to drop downstream through the falls to the sawmills.

Or as Thoreau noted in his journal: “It is vain to dream of a wildness distant from ourselves. There is none such.”

Thoreau was either resigned to or remarkably sanguine about humanity’s transformative as well as destructive impact on nature. He did not approve of the way “human activity was now the dominant agency driving landscape change,” as Thorson puts it, yet he quietly accepted it as part of the ongoing, ever-changing history of the earth.

What saved Thoreau from a gnashing of teeth was his awareness of how much wildness still surrounded him. One can’t help but marvel at the rapture that the sight of things like huckleberries, turtles, or wildflowers would inspire in him. There was clearly a sublimated libidinal surplus within him—nourished by his lifelong chastity—that rendered his relation to nature thoroughly erotic and ecstatic, even in the midst of the anthropocene spectacle in its most demoralizing forms.

Kevin Dann claims that “throughout his life, Thoreau was certain that his ‘property’—his soul—was immortal, destined to go to God again when he died.” That may or may not be true, yet it is certain that Thoreau believed there was more than enough heaven in this world to go around. For all his personal contradictions, he saw none between his immortal soul and the “hard matter” of his body, or between a transcendent heaven and a mortal earth.

Thoreau declared that he went to the Walden woods “to front only the essential facts of life,” for he did not want, when it came time for him to die, to “discover that I had not lived.” In her poignant and eloquent book, When I Came to Die, Audrey Raden shows how, for Thoreau, death and dying were among the most essential facts of life, and that to live life to the fullest meant to live it in full awareness of its mortality.

In Bird Relics, Branka Arsić delves into Thoreau’s writings, with particular attention to the Indian Notebooks and unpublished bird notebooks, to trace the way his thinking about nature developed over the years into a kind of pan-vitalism, which sees the generative forces of life at work in death, disease, and natural decay. For Thoreau the latter are not opposed to, but are part of, life. Arsić gives due emphasis to the crucial part that the death of his brother John played in Thoreau’s understanding of the all-encompassing force of life. Thoreau was so deeply bonded with his brother that, in a psychic if not physical sense, he died with John in 1842. His grief was as intense as it was prolonged and, as Arsić suggests, it helped incubate his philosophy of life. He emerged from it believing that whatever was alive in John lived on in the regenerative nature of the surrounding landscape. Thoreau’s grief lies behind his calm acceptance of death, which life absorbs back into itself and from which it engenders new life.

It is no doubt because he lived a life of daily contact with the real—with nature in its everyday miracles—that Thoreau died a “beautiful death,” as it was called in those days. It was beautiful not because it was painless (he died of tuberculosis in his family home at forty-four) but because he faced his approaching death with remarkable serenity and even cheerfulness, convinced that death was not so much the termination as the consummation of life.

When Thoreau’s abolitionist friend Parker Pillsbury visited him shortly before he died and found him “deathly weak and pale,” he took his hand and remarked to Thoreau, “I suppose this is the best you can do now.” Thoreau smiled and “gasped a faint assent.” When Pillsbury then said, “The outworks seem almost ready to give way,” Thoreau whispered, “Yes,—but as long as she cracks she holds.” This was a saying common among boys skating on the thinning ice of lakes and ponds, meaning that as long as the ice cracks, winter still holds.

By his own account Pillsbury then remarked to Thoreau, “You seem so near the dark river, that I almost wonder how the opposite shore may appear to you.” Thoreau’s answer remains, for all intents and purposes, his last word: “One world at a time.”

Thoreau had an almost mystical reverence for facts, above all the fact of death. In Walden he wrote:

If you stand right fronting and face to face to a fact, you will see the sun glimmer on both its surfaces, as if it were a cimeter, and feel its sweet edge dividing you through the heart and marrow, and so you will happily conclude your mortal career. Be it life or death, we crave only reality.

Among Americans nothing has more authority than facts. Of course the contrary is also true (a quarter of Americans believe the sun revolves around the earth; more than three quarters believe there is indisputable evidence that aliens have visited our planet). Is it true that we crave reality? Yes, but we crave irreality just as much if not more. Our addiction to our television, computer, and cell phone screens confirms as much. As for death, it does not seem that today we have a knack for concluding our mortal careers “happily.”

I believe there are two immensely important Thoreauvian legacies that call out for retrieval among his fellow citizens today. One is learning to live deliberately, fronting “only the essential facts of life,” so that death may be lived for what it is—the natural, and not tragic, outcome of life.

The other equally important lesson is how to touch the hard matter of the world, how to see the world again in its full range of detail, diversity, and infinite reach. Nothing has suffered greater impoverishment in our era than our ability to see the visible world. It has become increasingly invisible to us as we succumb to the sorcery of our digital screens. It will take the likes of Henry David Thoreau, the most keen-sighted American of all, to teach us how to discover America again and see it for what it is.

-

1

The view of Thoreau as a hypocritical jerk is alive and well. In an article about Walden in The New Yorker (October 19, 2015), Kathryn Schulz works herself into a froth of indignation as she denounces him for his “hypocrisy, his sanctimony, his dour asceticism, and his scorn,” claiming, as many others before her have, that “he was as parochial as he was egotistical.” Thoreau does Schulz one better in Walden, where he writes: “I never knew, and never shall know, a worse man than myself.” ↩

-

2

On the symbolic meaning of Thoreau’s departure from Concord to the shores of Walden Pond on Independence Day, see Stanley Cavell’s The Senses of Walden (Viking, 1972), still one of the most thoughtful books about Walden ever published. ↩

-

3

See The Journal, 1837–1861, edited by Damion Searls with a preface by John R. Stilgoe (New York Review Books, 2009). ↩