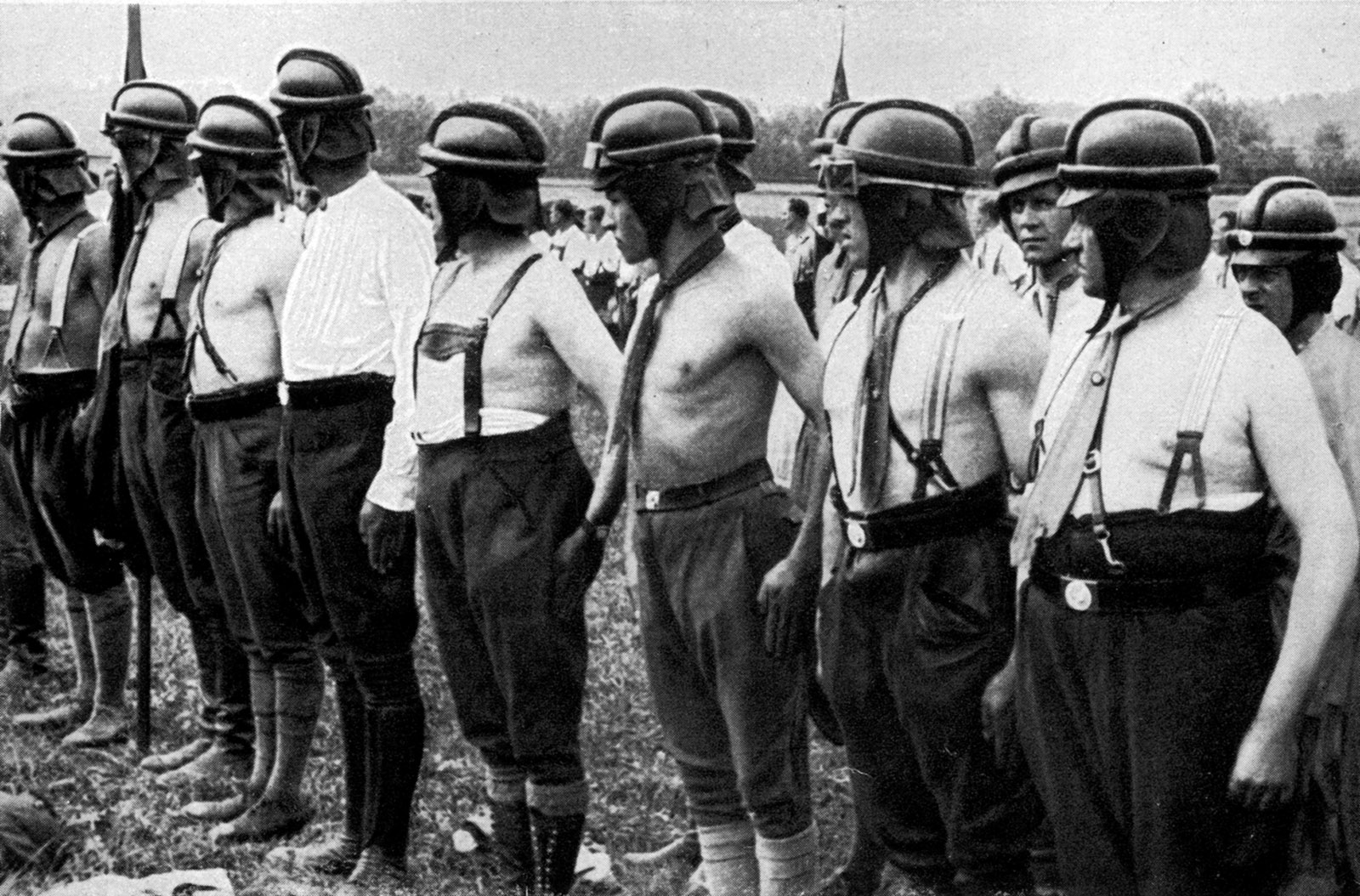

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Stormtroopers without their brown uniforms, which were banned by German authorities several times between their introduction in 1926 and Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933. Daniel Siemens writes that an ‘SA troop…with members dressed in white shirts or other surrogate “uniforms” still remained highly recognizable.’

The torchlight parade of some ten to fifteen thousand brown-shirted stormtroopers through the streets of Berlin on the night of Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor of Germany in January 1933 is certainly one of the best-known images of the Nazi era. It is no surprise, then, that it was invoked last August by a few hundred American white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia, at the moment they openly admitted their identification with National Socialism by chanting “Blood and Soil” and “Jews will not replace us” and carrying the swastika flag alongside the Confederate flag. But who exactly were the stormtroopers, members of Hitler’s SA (Sturmabteilungen, or Storm Sections), whom the Americans were trying to emulate? Daniel Siemens’s new book, Stormtroopers, provides us with an up-to-date answer to that question. It varies in some ways depending upon which period of the Nazi era one is looking at, but there were also features of the SA, Siemens notes, that remained fixed throughout.

The constants of the SA were violence and racism. It was a paramilitary group composed above all, as Siemens notes, of “communities of violence.” Violence was rational and purposeful. It constructed identity, created sociability and a sense of belonging, and provided self-empowerment for the stormtroopers. It mobilized and unified them. It separated them from mainstream society and marked them as crusaders on behalf of a higher cause. It nourished “feelings of liberation”—above all a freedom to destroy. The higher cause was the national unity and social solidarity of the Volksgemeinschaft, or racial community of Germans, created by the exclusion of others and preserved through vigilant policing of that exclusion by the self-appointed guardians of racial purity, such as the SA itself.

As a fighting community, the SA was a subculture of militant masculinity that provided a surrogate family and an “emotional shelter” for its members. It created what Siemens calls a “lifestyle” based on “emotional excitement” rather than reason and an “alternative public sphere” for “extreme partisan views” not subject to “factual accuracy.” It rejected democracy, especially the divisiveness of political parties representing differing class and economic interests, in the name of a unity of race and conviction embodied in the bond between the people and the charismatic leader. Its sense of struggle against the old order as well as against Jews and Marxists made its members feel “relevant” within a “hostile” environment. Unresolved were potentially troubling questions about just how anticapitalist the SA’s populism was and just how much social change at least some of its members would demand should the movement succeed in coming to power. In the meantime, the emotional satisfaction of violence against and destruction of the community’s enemies was a far greater priority than programmatic planning for the future.

The history of the SA, according to Siemens, should be divided into three phases, the first of which was its early struggle as a paramilitary organization in southern Germany, especially Munich, up until Hitler’s failed attempt to take over the Bavarian government in the Beer Hall Putsch of November 1923. In the immediate period after World War I, Germany (and especially Bavaria) was awash with paramilitary activity involving some 400,000 men. Parties across the political spectrum had self-protection units, and the infant National Socialist Party’s force initially numbered only a few hundred men, mostly youth with a sprinkling of World War I and Freikorps veterans. The latter consisted of paramilitary formations officially sanctioned in 1918–1919 by the new Republican government to defend it against challenges further from the left.

Shielded by the police, armed by the military, and favored by the judiciary as healthily nationalist, anti-Marxist, and anti-Semitic, the young Nazi stormtroopers could bait their rivals or invade working-class districts at relatively low risk. The success of Mussolini’s squadristi and his assumption of power in Italy following the “march on Rome” in October 1922 led to a rapid growth of the Nazi paramilitary to over three thousand in Bavaria in 1923 who hoped to emulate Mussolini’s triumph. But unlike in Italy, the military and police backed away from supporting Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch, when it appeared that the recently installed Stresemann government in Berlin was pulling the Weimar Republic back from the precipice of total collapse. Hitler was arrested, tried, convicted, and briefly jailed, and his stormtroopers were dissolved.

The stormtroopers were soon resurrected (now officially designated the SA) as a hierarchical mass organization with distinct brown-shirt uniforms. In line with Hitler’s new tactics of legality—his decision to attempt to come to power in Germany through electoral politics—the SA was used for both confrontation and propaganda. In cities it fought to stake out territory. In small towns and rural areas, its members eventually experienced even greater growth through incessant campaigning and recruiting. By September 1930 the SA numbered 60,000; after Hitler’s breakthrough in elections that month—the party jumped from twelve to 107 seats in the Reichstag—it grew to 221,000 members by November 1931 and 445,000 by August 1932.

Advertisement

By then the field of paramilitary competition had been winnowed down to four main contenders: the SA, the Social Democrats’ Reichsbanner, the Old Right’s aging Stahlhelm, and the Communists’ Rote Frontkämpferbund. If the Reichsbanner and Stahlhelm preferred to restrict themselves to the relative safety of marching and demonstrations, the SA and Communists confronted one another in unfettered street violence. The high casualty rate they experienced in comparison to their rivals was compensated for by the prospect of elevation to Nazi martyrdom.

There were serious tensions within the SA as well. These were twofold. First, when Hitler refounded the Nazi Party in the mid-1920s, he emphasized nationalism over socialism. But a Nazi left, with adherents concentrated in the SA, advocated a more explicitly socialist and anticapitalist populism, and Hitler stamped out the “revolts” of several of these dissident SA units in the early 1930s. Second was increasing frustration with the “tactics of legality,” as the party’s growing popularity and electoral success failed to put Hitler in power. Particularly by late 1932, electoral exhaustion, frayed finances, and demoralization threatened the party’s assumptions about its invincibility and the inevitability of its taking control of Germany. President Paul von Hindenburg’s appointment of Hitler as chancellor (without his obtaining a parliamentary majority through elections or coalition-building) saved the party at a moment of impending crisis.

The SA’s celebratory torchlight parade on the night of January 30, 1933, was followed by an explosion of violence that released pent-up emotions (according to Siemens, a mixture of revenge, hate, rage, excitement, and ecstasy), killed five hundred to a thousand and injured thousands more, and “communicated the new Nazi code of behaviour to everyone.” Physical and psychological torture was meant to humiliate and degrade opponents so that both they and bystanders would forever be deterred from venturing into politics again.

For the SA, success was its own nemesis. Hitler’s victories over his opponents and his deluded right-wing partners as well as his consolidation of his dictatorship were so rapid and complete that he could declare a one-party state and an end to the revolution in July 1933. Without real political opposition, further SA violence had become redundant until new targets were found. SA membership exploded to four million by spring 1934. Most of these additional members were opportunists jumping on the Nazi bandwagon. But half a million of them came through the absorption of the conservative Stahlhelm, while many so-called beefsteak Nazis—former Communists, socialists, and labor unionists whose own organizations had been banned and who were now suspected of being brown on the outside but still red on the inside—also joined.

In short, all the repressed conflicts of German society were compressed into the SA, which was the largest Nazi mass organization. The resentments of “old fighters” who felt unrewarded for their previous sacrifice and greatly outnumbered by undeserving newcomers were easily stirred by the ambitious head of the SA, Ernst Röhm, who called for a “second revolution” and demanded that the basis of German rearmament be the SA as a politicized people’s militia, rather than the country’s small 100,000-man professional army and officer corps.

Röhm’s party rivals, Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Göring, as well as the officer corps, pressed the reluctant Hitler to terminate the threat that Röhm posed to them, and they finally prevailed. On the “Night of the Long Knives” or “Blood Purge” of June 30–July 2, 1934, Röhm and top SA leaders as well as a long list of enemies Hitler had accumulated over his career—including a previous chancellor of Germany, Kurt von Schleicher, his wife, and the closest associates of Hitler’s own Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen, who had belatedly persuaded him to deliver a speech critical of the Nazi regime—were summarily executed. In openly proclaiming his right to order extrajudicial mass executions, Hitler cited both trumped-up charges of treason and the homosexual depravity of Röhm and his clique of SA leaders. Röhm’s open homosexuality had never been a problem for Hitler earlier, but the opportunity to win public acquiescence to this mass killing by defending it as a preemptive strike on behalf of decency and moderation against degeneracy and radicalism was a temptation not to be passed over. As a political ploy, it was entirely successful. Many hitherto uneasy Germans breathed a sigh of relief that normalization had prevailed and the most violent, populist, and revolutionary elements of the Nazi movement had been eliminated.

Advertisement

As both Siemens and Andrew Wackerfuss in his pioneering Stormtrooper Families1 have noted, the consequences of Hitler’s homophobic scapegoating were catastrophic. Most important, by helping to frame and murder his rival and boss, Himmler won independence for the SS (Schutzstaffel, or Protection Squadron), which had previously been subordinate to the SA. This in turn freed Himmler, the most ardent homophobe among the Nazi leaders, to carry out a fierce persecution of gay men in Germany for the remainder of the Third Reich.

Moreover, Hitler’s scapegoating advanced the myth of the “gay Nazi” that has been politically exploited on both the right and the left. Given the homosocial nature of SA units (surrogate all-male families) and the homoerotic overtones of the male bonding and comradeship that the SA emphasized, even before the Blood Purge some on the left—such as the journalist Helmuth Klotz, who published Röhm’s private love letters in 1932, or those who jeered at SA men with chants of “Gay Heil” (Schwul Heil)—tried to exploit anti-homosexual attitudes. They alleged a connection between homosexuality and stormtroopers, between moral and political depravity, regardless of the cost to gay men of such innuendos—a shameful tactic that did not end in 1934 or even 1945. And on the right today, anti-gay crusaders like Scott Lively have equated gays with Nazism as an utterly hypocritical justification for Himmler-like criminalization and persecution of homosexuality worldwide.2

Siemens labors mightily to make a case for the ongoing importance of the SA after the Blood Purge, despite the fact that within four years it had lost roughly half its membership due to apathy and demoralization. Unmentioned by Siemens was yet another factor, namely the cool and opportunistic calculation of many who simply shifted their allegiance and membership to the SS—a common career trajectory among rising Nazis in the mid-1930s. Those who remained in the SA became military trainers, dominating in particular groups connected with preparation for war, such as shooting and riding clubs, and trying to infuse society with the values of militant nationalism and masculine toughness.

Precisely because these new duties were so banal in comparison to the real street battles its members had fought during the years of “heroic” struggle, the pressure within the SA to vent pent-up aggression found one remaining outlet in racial policing and anti-Semitic violence. Presiding over public rituals of humiliation of those who dared to step across the new racial boundaries, the SA deterred many from showing any sign of solidarity or friendliness toward Jews and thereby helped to create the fictive consensus in support of the regime’s anti-Semitic policies. Though often reined in when its violence threatened property and economic recovery, the SA was unleashed for one last orgy of violence and destruction in the November pogrom of 1938, Kristallnacht.

With the outbreak of World War II, the importance of the SA diminished further. The SS easily eclipsed it, seizing a leading part in mobilizing ethnic Germans abroad and carrying out Hitler’s demographic revolution on the territories of Germany’s new Lebensraum. The main contribution of the SA to the Final Solution was made by five SA generals who were seconded to the Foreign Office to serve as ambassadors to Germany’s southeast European allies (Slovakia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary), where they helped arrange for local cooperation in the killing of the region’s Jews.

By early 1941, 70 percent of the SA’s rank and file and 80 percent of its officers had been conscripted into military service, and others served in the police and administration of the occupied territories. All these men now answered to a different organizational hierarchy and no longer fell under SA management. It may well be that these millions of former SA men acted on their previous institutional culture of violence and racism in their new capacities and helped imbue the military, police, and occupation administrations with these values and behavioral standards.

The International Military Tribunal decided not to include prewar offenses under the “crimes against humanity” indictment, and thus the SA actions during the seizure of power and Kristallnacht were not considered. As a result, unlike the SS, the SA was not declared a “criminal organization” by the Nuremberg tribunal. According to Siemens, “slowly but surely the SA as an organization that had not only contributed to the Nazi terror, but also shaped the lives of millions of German men and their families, vanished from public memory.” After the war, an exculpatory myth emerged that the SA had been insignificant after 1934, which affected German historical writing and allowed the postwar careers of some SA men to flourish.

However, Siemans’s concern with discrediting this myth leads him to entirely ignore a second exculpatory myth, that of the “clean Wehrmacht,” which in turn raises a significant question about assessing the legacy of the SA. In the postwar accounts of various purveyors of this second myth, the victories had been won by the German generals, the defeats were due to Hitler’s amateurish interference, and the atrocities had all been committed by the SS. The alienation of the native populations of the Soviet borderlands who had initially welcomed the Germans as liberators was caused by the corruption, incompetence, and brutality of the SA men who staffed the civil administration of Alfred Rosenberg’s Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories. These SA men, decked out in pretentiously spiffed-up brown uniforms that represented noncombatant standing, self-importance, and bottomless greed, were scornfully known as “Golden Pheasants,” or Goldfasanen.

This account, which blames Germany’s defeat and atrocities on everyone except the German military, nonetheless raises several legitimate questions not addressed in Siemens’s study. How prevalent were SA men within the civil administration of Germany’s occupied eastern territories, and to what extent did their culture of violence and racism—combined with a sense that they were entitled to self-enrichment in compensation for their previously underrewarded sacrifices on behalf of the Nazi cause—contribute to Germany’s lethal and self-defeating policies?

Subsequent history writing has restored the SA as an enduring symbol of Nazi violence and racism, one that had an important part in the Nazi Party’s assumption and consolidation of power as well as its subsequent policing and penetration of society. But it was not the primary instrument of Nazi conquest, exploitation, and mass killing as experienced by other Europeans. Until 1939 Hitler remained well back in the ranks of notorious mass killers of the interwar period. Certainly Stalin, with a state-caused famine that claimed some five million lives in the course of collectivization, more than 800,000 executions during the Great Purge of 1937–1938, and some 1.5–3 million victims of the Gulag, was firmly in first place.3 Mussolini, with a near-genocidal repression in Libya and the infamous conquest of Ethiopia (which included the use of poison gas), vied with Franco and his mass executions during and after the Spanish civil war4 for second and third place in Europe, while in Asia Japan’s mass killings in Manchuria and China culminated in the Nanking massacre.

After September 1939, however, Hitler rapidly overtook his rival mass killers, not through the SA but rather through far more respected organizations: the German medical profession with its notorious experiments and murders of the mentally and physically handicapped; corporate Germany with its thousands of labor camps and millions of enslaved and forced laborers; the Wehrmacht with its lethal POW camps for captured Soviet soldiers, antipartisan sweeps, reprisal executions, and “dead zones”; the ministerial bureaucracy with its expertise and legal cover for many Third Reich policies; and above all the SS with its Einsatzgruppen, death camps, and the Final Solution. In the end, it was not the SA and its early party faithful but rather these more elite organizations in Germany that mobilized and organized countless “ordinary” Germans to accomplish the regime’s most lethal policies. Nonetheless, the SA as a symbol of Nazi hate, violence, and racism has endured, as the theatrics of white supremacists in Charlottesville and the horrified reaction of almost all Americans have shown.

This Issue

April 5, 2018

Bang for the Buck

Beware the Big Five

As If!

-

1

Andrew Wackerfuss, Stormtrooper Families: Homosexuality and Community in the Early Nazi Movement (Harrington Park, 2015). ↩

-

2

Scott Lively and Kevin Abrams, The Pink Swastika: Homosexuality in the Nazi Party (Founders, 1995). ↩

-

3

Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (Basic Books, 2010), pp. 27, 53. ↩

-

4

Paul Preston, The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain (Norton, 2012). ↩