April 1992: buildings burned, stores were looted, people were killed. An all-white jury in a suburb of LA had just acquitted four white police officers who had been captured on a camcorder brutally beating Rodney King, a black motorist, the year before. When the verdict was announced, no one could believe it. What ensued, depending on whom you talked to, was “a riot,” a “social explosion,” “a revolution.” Some politicians and academics, waiting to see how the dust settled, chose to call it “the events in LA.” People stood on rooftops watching the fire and smoke, terrified for their property or lives, estimating how long it would take for the violence to get to them. But the destruction stayed pretty much in South Central and areas immediately surrounding it—Koreatown and the lower Wilshire area. It never got to the shops in Beverly Hills. The cry and anthem in the street was “No Justice—No Peace!”

After the news crews packed up their gear, I slipped into LA and moved around the city and its surrounding areas, gathering stories: Simi Valley, Beverly Hills, Hollywood, Koreatown, and the epicenter of the riot, South Central. In South Central I talked with many people, including a former member of the Black Panther Party, who was among those who fleshed out the background to what had happened. He had the demeanor of a wise man with his graying dreadlocks, and he spoke about the war between black and brown men and the Los Angeles Police Department, which he knew well from when he was in the BPP during the 1970s. He saw the impact that the war was having on the young brothers he worked with in the 1990s—members of gangs and ex-members of gangs.

It occurred to me in the middle of my conversation with the ex-Panther that “No Justice—No Peace” was to the Los Angeles riots and the incidents that had led up to them what “All Power to the People” had been to the rise and fall of the Black Panther Party. I asked, “Hey, has ‘No Justice—No Peace’ taken the place of ‘All Power to the People’?” After pondering for several seconds, he burst out, “Oh no! Ain’t nothin’ ever gonna be as powerful as ‘All Power to the People’!” If memory serves, I believe we finished the moment off with a rejuvenating high five and our black power fists shooting up in the air.

At the end of the 1960s and 1970s, some (but hardly enough) power got shared. Yes, blacks could sit at lunch counters and shop in department stores, but whom did that benefit? The business owners and the bankers. The color of the owners and bankers did not change enough to make it notable. There was a black arts movement in the 1960s, but that in no way changed who ran the movie studios. That is still the case today.

We moved from a desire for power to a desire for justice. “No Justice—No Peace” spoke to the dismay many felt in the face of a legal system that protects power at the expense of justice. The slogan has been with us for more than twenty-five years, and it has brought us up to this moment. It is still chanted every time a police officer kills or shoots someone who appears to have been denied due process.

The megahit film Black Panther, released fifty years after the cultural rebellions of the 1960s, has elicited much praise. The loudest praise concerns the bottom line. It is among the ten highest-grossing films ever made. Many of its black fans praise the fact that the director, Ryan Coogler, is black and that the cast and creative team are almost entirely black. It has been difficult to get such a movie made. Coogler did it. It is only right that these fine artists were able to grab an opportunity and succeed glowingly. The movie’s financial success is a kind of claim on power. Will “No Justice—No Peace” be replaced by “Wakanda Forever”?

The focus of Black Panther is a superhero from the Marvel Comic Universe, T’Challa, the Black Panther (played by Chadwick Boseman), who is also a king. After the sudden death of his father, T’Chaka, T’Challa has inherited the throne of the Kingdom of Wakanda, a country in Africa and a utopia in the tradition of El Dorado and Shangri-La. Unmarked by the evils of colonialism, Wakanda is beautiful. It is also wealthy because it has a very valuable metal—vibranium.

Wakanda has survived by largely cutting itself off from the world, but this strategy is questioned in the course of the film. Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan), the cousin that King T’Challa did not know he had, shows up and disrupts utopia. He seeks to take the throne, change the values upon which Wakanda is based, and change its position in the world. In battle, he pushes T’Challa off a high cliff to his death, and that appears to be that.

Advertisement

Killmonger is competitive; he behaves with no decorum. He has some of the same traits as President Trump. As questionable and distressing as his behavior is to some, once he has the throne, Killmonger gains the support of many in Wakanda, including the head of the fabulously powerful all-female security guard, Okoye (Danai Gurira). In a way that people will have to see for themselves, the throne is restored in the end to T’Challa, who did not die after all.

The Black Panther character has a long, rich history. Seeing an opportunity to bring a black superhero into the almost entirely white comic book world, Jack Kirby, a Jewish artist, introduced the Black Panther into the world of the Fantastic Four in 1966. Stan Lee, the former publisher and chairman of Marvel Comics and who had a cameo in the movie, was cocreator. The Black Panther comic book character predated the Black Panther Party by a few months. Not wanting to carry the baggage of the controversial BPP, Marvel at one point changed the character’s name to the Black Leopard, but the original name prevailed.

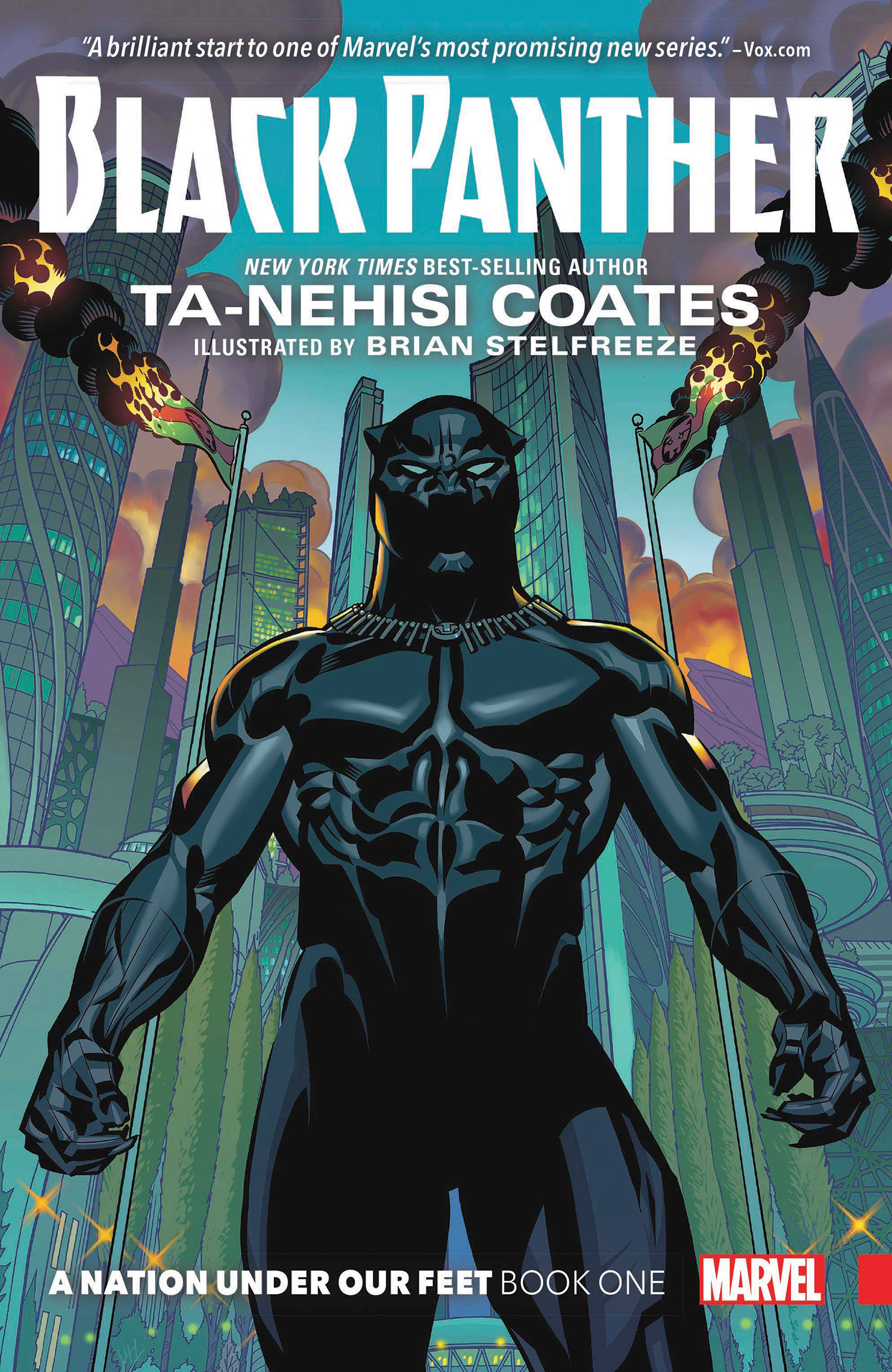

The Black Panther had many permutations. Christopher Priest in the late 1990s and early 2000s and Reginald Hudlin in the mid-2000s, both African-American, wrote comics in the series. They are said to have given the character a more Africa-centered, self-determining ethos. Most recently, Ta-Nehisi Coates, following the extraordinary success of his Between the World and Me (2015), was approached by Marvel to write a Black Panther series with the illustrator Brian Stelfreeze, and another chapter in the life of the superhero was born.

The principal artists in the film had not worked on any production of this scale before. Coogler and his core company—Michael B. Jordan, the cinematographer Rachel Morrison, the composer Ludwig Göransson, and the production designer Hannah Beachler—had worked together since Coogler’s exquisite film Fruitvale Station (2013). To that team, Coogler added the costume designer Ruth Carter, who had worked on large productions before, Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992) among them. Some of the actors are not only veterans, they are movie royalty, for example Angela Bassett and Forest Whitaker, and from South Africa, John Kani. Others are among the best of their generation: Lupita Nyong’o, Boseman, Gurira, Daniel Kaluuya, Sterling K. Brown.

The relative newcomer Letitia Wright, who plays T’Challa’s sister, Shuri, is fresh-faced in every way. Early in the film, her brother is required to solidify his position as king in ritual combat following the death of his father. Breaking the intensity of the ceremony, Shuri protests about the corset she is wearing, wishing to speed things along so she can take it off. She represents a new type of young black woman—a science genius who spends her days in a lab making inventions and powering what she invents with vibranium.

Boseman, whose disciplined and often subtle performance is at the center of the wonderful acting ensemble, was asked by Brooke Anderson on Entertainment Television to differentiate between working on the sets of Black Panther and Captain America: Civil War (2016), the film in the Avengers series in which he played the Black Panther for the first time. He replied:

There’s a certain amount of comfort with Avengers because it’s been done before…. We are all comfortable with each other and we have a lot of fun. Not that we didn’t have fun on the Black Panther set, but it was a new thing and you don’t quite know what it’s supposed to look like or sound like or feel like so it’s a lot more pressure and angst on the Black Panther set.

But it was a new thing and you don’t quite know what it’s supposed to look like or sound like… There couldn’t be better conditions for innovation and creativity. And yet they had to meet a high bar. They jumped with the catlike dexterity of the Panther himself, from a low-budget work to one that is mainstream and epic in scale. In an interview, Hannah Beachler spoke about having worked with smaller budgets on smaller projects. For Black Panther she had to manage three hundred people.

For my second viewing, I sat in the back of a theater with one of the American film industry’s most accomplished production designers as she whispered to me, pointing out where computer-generated imaging was used, where it wasn’t, etc. Just as Kirby and Lee brought the Black Panther into the world of comics at the right time, Coogler, Disney, and Marvel have brought the Black Panther into the world of film at the right time. Without the technological accomplishments in film that predate Black Panther, its captivating beauty, breathtaking views, and edge-of-your-seat moments would not be possible.

Advertisement

It is obvious that Disney and Marvel had Coogler’s back. Filmmaking is collaborative. The producers are essential. Money needs to flow. This production must have had a squadron of veteran participants, many of whom, most likely, given the demographics of Hollywood, were not black, but supported Coogler’s vision. The movie hit screens around the world following #OscarsSoWhite, #MeToo, #TimesUp, and #BlackLivesMatter, with its continuing relevance. A student of mine, a talented young black writer, believes this is a sign that doors will open for him. I hope that’s true.

Black Panther was transformational to many people. Many talked about what it meant to see black folks in power. Black American males in particular talked about what it meant to “see themselves” up there on that screen. Women have commented on how thrilling it was to see powerful black women: T’Challa’s ex, Nakia (Lupita Nyong’o); his sister, Shuri; and the all-female security guard, the Dora Milaje, led by Okoye. It could go without saying, but it shouldn’t, that Ramonda, the queen mother, as played by Angela Bassett, reigns as only Angela can.

Ryan Coogler gave audiences over two hours of pleasure, fear, excitement, sexiness, and beauty. We have an opportunity to take the delight it has pricked and do something with it. If in fact the movie is transformative, will the transformation stop the moment we leave the theater, with the empty popcorn bucket lying on the carpet, the twisted straw from the soda under the seat? There is a conversation to be had.

For now, the conversations with the widest reach are the ones manufactured by the entertainment industry. Those conversations are geared toward selling things. They evoke our desire and our fandom but they leave us in a state of passive observance. Chadwick Boseman has forty cousins. That’s interesting. How does Michael B. Jordan get in shape? I took notes myself—he drinks so much water he can’t sleep through the night. He works out six times a day. “How long are your workouts?,” talk show hosts asked, the female ones leaning forward and gazing at his muscles, the male ones sitting back and grinning. He dodged the question and said it wasn’t about the time—and with a wide welcoming smile, obviously understanding that his job as a movie star is to spread his charm. Keep it light. Swimmers say it’s what’s happening under the surface of the water that gives you speed.

An ancillary benefit of the movie could be the small but not inconsequential pockets of conversations about the condition of black people in America. But just keeping it light won’t get us there. Elaine Brown, former chairwoman of the Black Panther Party, had this to say about buying into the drama of transformation, of revolution:

If you are committed—if you seriously make a commitment (and that commitment must be based not on hate but on love)…then you gon’ have to realize that this may have to be a lifetime commitment…. So don’t get hung up on your own ego and your own image and pumping up your muscles and putting on a black beret or some kinda Malcolm X hat or whatever other regalia and symbolic vestment you can put on your body. Think in terms of what are you going to do for black people. I’m saying that these are the long haul.

A sense of self comes from the mirror in which you see yourself—and it also comes from gathering information about how others see you. For eight years, the world saw two powerful, beautiful, sexy black people: President and Mrs. Obama. I heard as many, if not more, passing remarks about the first lady’s “guns” as I did about the work she was doing to draw attention to the health and well-being of children.

Inauguration Day 2008 was historic because we defied history and elected an African-American president—one with an actual African father. One promise of that day was how much it would mean for little black boys and little black girls to see themselves in the White House. I watched the redcaps at Union Station prance with pride as they hauled luggage off the train, and the lightness of their step was not just because some of the luggage was Beyoncé’s.

There is a need among black Americans to see ourselves in power. Coogler, Disney, Marvel, and company have tapped into that need—and they have profited from it. The need is not unique to blacks. For example, several of Black Panther’s action sequences were filmed in Busan, South Korea, and a Korean moviegoer spoke in an interview about how much he’d like to see a major motion picture with Korean superheroes.

What is it about the human condition that causes us to need to see ourselves in art forms? Is it that art forms are meant to be mirrors? Have racism and tribalism so infiltrated the manufacturers of art that distortion has prevailed? Does a project like Black Panther, even as it focuses on one world, help fix the mirror itself?

A.M. Bernstein is a physicist I talked to when I was trying to understand some things about racial identity. We wound up talking about mirrors—real mirrors, not metaphorical ones. He said:

So a simple mirror is just a flat, reflecting substance, like, for example, it’s a piece of glass which is silvered on the back. Physicists talk about distortion. It’s a big subject, distortions. I’ll give you an example—if you want to see the stars, you make a big reflecting mirror. That’s one of the ways. You make a big telescope, so you can gather in a lot of light and then it focuses at a point. And then there’s always something called the circle of confusion. So if ya don’t make the thing perfectly spherical or perfectly parabolic—if there are errors in the construction which you can see, it’s easy, if it’s huge, then you’re gonna have a circle of confusion, you see?… If you’re counting stars, for example, and two look like one, you’ve blown it.

It would seem that everyone would benefit from a mirror without distortion. It would be better to see two stars than two stars that look like one. We have worked on fixing the distortion before. The original Roots series was one very important correction. Roots, however, set its heroes in frightening surroundings, and they were victims of cruelty and the capriciousness of power. Black Panther sets the superheroes in their own land and they are not victims, they are royals.

I am perplexed about Erik Killmonger, T’Challa’s cousin, who comes to take away the throne. We learn in a flashback about his father, N’Jobu (Sterling K. Brown), who left Wakanda for the US and met an American woman there. They live in Oakland, the birthplace of the Black Panther Party. Unlike his brother, King T’Chaka, who has kept Wakanda in isolation, N’Jobu comes to believe that Wakanda should use the power and value of vibranium to start an international revolution and liberate the oppressed peoples of the world.

N’Jobu betrays T’Chaka. He reveals the presence of Wakanda to a black-market arms dealer from South Africa—one of only two white characters in the movie—who plans to infiltrate the country and steal vibranium. T’Chaka confronts N’Jobu in his Oakland apartment, kills him, and leaves his body for his son to find.

Erik grows up to be what looks like a winner. He goes to MIT. He gets a piece of the American dream. He becomes a Navy Seal, then a black-ops soldier who specializes in targeted assassinations. He takes the name Killmonger and lines his body with tattoos that stand for the many lives he has claimed.

The American dream, which would seem to be firmly in Erik’s grasp, cannot cure what was taken from him when his father was killed. He is filled with rage. Does Erik’s pain and brokenness suggest that even if a black male is successful in this culture, even if he climbs to the top, even if he serves the nation and is rewarded for it, he feels a loss? A loss that cannot be filled by, say, more of America? Erik is broken. The Black Panther has succeeded in giving some black viewers a feeling of being whole.

We won’t know for a while if the effect of Black Panther goes beyond the box office, the proceeds of which will lie, for the most part, in the palms of the producers. We won’t know how long the door will stay open for more artists of other colors to make their way through. We won’t know how long it will take for a Latino superhero or an Asian superhero to have a movie, or a woman of color superhero to have her own movie, or if and when a trans superhero will walk the world stage with the grace and power of the Black Panther.

We won’t know if a judge, having seen Black Panther, will think differently in sentencing a black man or woman standing at the bench. We won’t know how Black Panther will affect kids in schools. We won’t know if the character of Shuri will be enough to encourage a girl to become a physicist. Will Shuri have made it any easier for women heading to Silicon Valley to gain opportunity and respect? There’s a lot we don’t know. But anyway.

Wakanda Forever! For now.

This Issue

May 24, 2018

Crooked Trump?

Freudian Noir

Big Brother Goes Digital