It is now clear that Turkey, a country to which Western visitors have often applied adjectives such as “timeless” and “slothful,” is changing profoundly, and with un-Oriental speed. To the many Turks who welcome this transformation, it holds out the promise of a free public culture, equally open to devout Muslims, secularists, and critics of Turkey’s past politics—something the country has never known. A smaller but nonetheless considerable number see the changes as a Trojan horse for Islamism as severe as one finds in Iran or Saudi Arabia. These two views come into sharp conflict on the subject of Abdullah Gül, whom the Turkish parliament recently elected president.

Abdullah Gül is a conscientious Muslim. He says his prayers and observes the Ramadan fast. His wife appears in public with a silk scarf wound tightly around her head. Although he was once associated with Islamism of a rather virulent kind and was a member of the Welfare Party, whose stated goal was to challenge Turkey’s secular traditions, Gül gives the impression of having mellowed. As foreign minister in the mildly Islamist government of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan from 2003 until his election to the presidency, Gül directed his energies mainly at promoting Turkey’s claims to EU membership. As president, he has promised to safeguard Turkey’s secular regime.

Gül is not a member of Turkey’s establishment. He is the first Turkish president in decades to have come from neither the armed forces nor the bureaucracy; his father was a machine worker in Kayseri, a provincial town in central Turkey that is known for both its piety and its entrepreneurial spirit. Compared to the outgoing president, the socially awkward secularist Ahmet Necdet Sezer, Gül seems worldly and cosmopolitan. He studied in England and, in the 1980s, worked for eight years as an economist for the Islamic Development Bank in Jeddah. He is an affable man, with a reputation for probity, and he is popular abroad.

Still, many Turkish secularists are appalled that Gül now occupies Cankaya, the pink concrete presidential palace in Ankara. For them, Cankaya is hallowed because of its association with modern Turkey’s founder, Kemal Atatürk. Cankaya—in its earlier, prettier, stone incarnation—is where Atatürk planned his expulsion of the Greeks and other Western invaders from Asia Minor following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire during the First World War. It is where he plotted to replace the empire with a republic. Most important, Cankaya is where Atatürk devised his great program of modernization, a “revolution” that secularized education and the law, emancipated women, and proclaimed the principles of “knowledge and science” that would henceforth guide Turkey’s development.

Since Atatürk’s death in 1938, the only Cankaya resident to have been perceived as a challenge to Atatürk’s secular legacy, Celal Bayar, was deposed in a coup in 1960—the first of four interventions by the Turkish military establishment, which sees itself as protecting the tradition of Atatürk. Subsequent presidents have generally erred on the side of authoritarianism in their adherence to Kemalism, the founder’s paternalistic political doctrine. In 1997, for instance, the president at the time, Süleyman Demirel, cooperated when the armed forces pushed an Islamist government out of power. During his tenure, Demirel’s successor Ahmet Necdet Sezer vetoed the appointment of hundreds of bureaucrats who were affiliated with Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) and pointedly failed to invite Erdogan’s wife to official functions—on the grounds that the law does not allow women with head scarves into official buildings. But Sezer has now retired to his lakeside villa near Ankara, and the Islamists—or the ex-Islamists, as some observers now call them—have conquered Atatürk’s castle.

It is worth recalling how this happened. Although the process of transition was tumultuous to begin with, it subsequently became calm, leaving grounds for hope that Turkey’s inevitable wider transformation will also be peaceful. Back in April, Erdogan abandoned his plans to run for president under pressure from the chief of the armed forces, Yasar Büyükanit, from Sezer himself, and from the hundreds of thousands of secular-minded citizens who took part in an anti-government rally in Ankara on April 14. But Gül, the second AKP choice, proved no more acceptable to the secularists, and a campaign started to prevent him from becoming president. Roused by anti-Islamist unions and the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), the secularists staged more protests in big cities.

On April 27, the Web site of the general staff carried a statement attacking the proponents of “a reactionary mindset whose sole aim is to erode the fundamentals of our state,” and vowing that the armed forces would, “if necessary, act…in a clear and unambiguous manner.” This was interpreted as a sign that a coup against Erdogan’s government was in the offing. A few days later, the Constitutional Court ruled that a quorum of 367 deputies had to be present in parliament for any vote on a new president to proceed. Because the CHP deputies duly failed to turn up, the number in attendance fell just below the court’s threshold, and Erdogan was forced to withdraw Gül’s candidacy.

Advertisement

Erdogan had called the general staff’s statement “a shot fired at democracy,” and it was through the democratic process that he sought redress. Rather than call his own supporters into the streets, which might have precipitated a coup, he announced early elections for July 22. As the head of a government whose performance, especially in managing the economy, had been impressive, Erdogan already stood a good chance of holding on to his parliamentary majority. The generals’ interference helped him further, allowing the AKP to present itself as having been wronged, and its supporters insulted, by an unelected military elite. Erdogan’s plan worked and the AKP won a stunning victory at the polls. His candidacy vindicated by the voters, Gül once again announced that he would stand for the presidency, and the chief of the armed forces indicated that this time he would not stand in his way. On August 28, Abdullah Gül became Turkey’s president.

It is hard to take seriously the more alarmist statements of Turkey’s die-hard secularists. As Erdogan deliberated on whether or not to run for the presidency, for example, Sezer claimed that Turkish secularism faced “its gravest threat” since the Republic’s inception—a statement that ignored the Islamist uprising that convulsed the Kurdish southeast in 1925 and the massacres of Alevis, members of a sect of heterodox Muslims, by Sunni bigots in the 1970s.

Since it came to power in 2002, the AKP has passed no overtly Islamist legislation. Erdogan tried to outlaw adultery, and some AKP mayors of provincial cities briefly set up alcohol-free zones, but these schemes met with protest and were abandoned. Erdogan’s education minister has been accused of Islamizing textbooks, and of packing his ministry with former employees of the Religious Affairs Directorate, but education remains, for the pupils at most state schools, a resoundingly secular experience. The AKP has not tried to limit or ban usury. Although it came to power promising satisfaction to those who chafe at the head-scarf ban, a highly controversial symbol of the secular–Islamist divide, it did not, in its first term, try to reverse this ban, and the sixty-two women it put up for election in July were all bare-headed. Moreover, over the past few years, the government has brought about what a recent report on women’s rights from the European Stability Initiative, a Berlin-based think tank, called “the most radical changes to the legal status of Turkish women in 80 years.”1 Under these reforms, rape in marriage and sexual harassment in the workplace were made criminal offenses, and sexual crimes in general were classified as violations of the rights of the individual. They had formerly been defined as crimes against society, the family, or public morality.

Ever since he became prime minister, Erdogan, who may have been chastened by the four months he had recently spent in jail for declaiming some Islamist verses, has been moving his party toward the center of Turkish politics. During the campaign, the far-right Nationalist Action Party (MHP) accused him in its election leaflets of expunging Islamic tenets from school textbooks in order to please the EU, and of promoting the activities of Christian missionaries. The leaflets contained photographs of Erdogan wearing a sinister Mason-like gown—apparently worn when he received an honorary degree from a Western university—and another of him with the Pope.

The AKP is related, historically and ideologically, to the Welfare Party, which briefly held power in the late 1990s in a coalition government that the armed forces toppled for promoting religious education and trying to turn Turkey away from the West. But much divides the two parties. It is hard to imagine today’s AKP, for instance, endorsing Welfare’s denunciation of the “order of slavery” imposed by “Zionism and Western imperialism,” or its prescription of “disinfectants” for the “microbes” of the capitalist banking system. Welfare’s parliamentary delegation was full of firebrands, including one who promised bloodshed on a scale “worse than Algeria” if the Kemalists pursued their secular aims. Many of these extremists were not invited to join the AKP when Erdogan set it up in 2001. Most of those who did join, and entered parliament the following year, were among the 150-odd sitting AKP deputies whom Erdogan removed from the party list before July’s election. They were replaced by candidates of his own choosing.

Advertisement

In July, a few days before election day, I was in Cankiri, a conservative, rural province in north-central Turkey, with one such handpicked candidate, Suat Kiniklioglu, who clearly does not correspond to the usual image of an Islamist. He wears a well-cut suit, speaks several languages, and has lived for long periods in Germany and Canada. Earlier this year, he resigned from his position as director of the Ankara office of the German Marshall Fund of the United States to contest the election from Cankiri, his father’s home province. As we drove to a rally outside the provincial capital, Kiniklioglu said he had joined the AKP to help it democratize Turkey. As a former member of the air force, Kiniklioglu regretted that the armed forces, “for so long at the vanguard of Turkey’s Westernizing project, have now been left behind by the people.” He intended, after his election, to help the government drum up support in sympathetic European capitals for Turkey’s EU candidacy and to counter the anti-Turkey sentiments of French President Nicolas Sarkozy and German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Kiniklioglu has since been made a government spokesman.

In Kiniklioglu’s view, Turkey must choose between a system dominated by “a small elite that has set itself apart” and “a democracy of the kind you find in Europe.” As the son of a Gastarbeiter who left Cankiri for Germany in 1961, Kiniklioglu feels no reflexive gratitude to the Kemalist bureaucrats, senior military officers, and traditional, monopolistic holding companies that have between them dominated Turkey for decades. On the contrary, his scathing reference to the “white Turks,” by which he means the pampered urban elite of Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir, with their inherited privileges and connections, is a reminder that alongside the conflict between Islamism and secularism there is another conflict, just as bitter, between Turkey’s old economic leaders and the outspoken nouveaux riches from the provinces.

Abdullah Gül’s home province of Kayseri, in the middle of Anatolia, over three hundred miles from Istanbul, has emerged on the winning side in this conflict. During twenty-five years of demographic and economic development, Kayseri has transformed itself from a backward region, dependent on the state for agricultural subsidies and industrial investments, into a place where one can see the private sector at its most ambitious and imaginative, and home to several of Turkey’s most profitable companies. Back in the 1980s, when Turkey was first exposed to global competition, Kayseri’s entrepreneurs invested in machinery and know-how; nowadays, the province’s industrialists, notably its furniture and textile manufacturers, are respected internationally. For sugar producers in the province, the recent phasing out of subsidies has turned out to be a blessing. Newly privatized, thriving in a competitive environment, Kayseri’s big sugar refinery has doubled its daily processing capacity. It is now Turkey’s second-most-profitable refinery.

Prosperity has changed the provincial capital, also called Kayseri. Having been, as recently as the 1960s, a modest little town, it has grown into a modern city with a population of 600,000 and amenities to match. Literacy rates have risen sharply, among women as well as men. The city has a well-established university, which receives private as well as public funding.

Why do many Turkish secularists feel uneasy as they view the strides taken by Kayseri and several comparable Anatolian towns? The answer lies in the growth of Islamic cultural autonomy that the new wealth has generated, and its apparent conflict with the principles of the secular state. Many of Kayseri’s top entrepreneurs are members of an association of religious-minded businessmen. They go on the pilgrimage to Mecca and host lavish breakfasts during Ramadan. They contribute to the building and upkeep of mosques, finance courses on the Koran, and help poor young people to attend university. The entrepreneurs of Kayseri are rich enough to buy large houses in Istanbul and villas on the coast, and to send their daughters to private universities—in this way, they can circumvent the head-scarf ban. Some are affiliated with Islamic religious brotherhoods, outlawed by Atatürk, that have been accused of undermining the secular order. The AKP is their natural political home.

Even when I visited Kayseri back in 1996, when Welfare was in power nationally and in the city, there seemed to be little appetite among residents for a full-blown Islamic regime. A report by the European Stability Initiative in 2005 described the people of Kayseri in an even more moderate light, as a community that has, by emphasizing Islam’s historical affinity to mercantilism, “made its own peace with modernity.”2

This cannot be said for many other parts of Turkey where change has been much more erratic and unsettling. Long before the AKP came to power, Turkey’s economic leap began with the partial economic liberalization of the 1980s and the beginning of the mass migration of poor people from the countryside to the cities. Under Erdogan, liberalization of the economy has gone faster and deeper. Backed by the International Monetary Fund, with which it has a standby agreement, the AKP has shown more fiscal and monetary discipline than any recent government. It has accelerated privatization and attracted record levels of foreign direct investment. The government has brought down inflation, which averaged almost 70 percent between 1996 and 2001, to below 10 percent. The economy is growing strongly.

Not all Turks have reaped the benefits, and many have felt only the costs. The increases in new jobs in private factories and the service sector have been offset as agriculture has shrunk, and thousands of small shops, unable to compete with new supermarkets and US-style malls, have closed. Despite the boom, unemployment has hovered around 2.5 million—10 percent of the workforce—since 2002; and unemployed workers have minimal benefits or none at all. Rural communities have continued to empty. The province of Cankiri, for instance, which once survived on agriculture, is now dependent on the remittances of some 700,000 migrants to Ankara and Istanbul.

The AKP is also the party of these migrants. Confused, alienated, and far from home, they find in the AKP an outlet for their conservatism and a vehicle for their material aspirations. In Erdogan, the son of a migrant to Istanbul, they have an example to admire. Their feelings are not shared by the established urban middle class. Many educated secularists deplore the newcomers’ manners and customs, and they resent what they perceive as an erosion of civic and urban values. Having to act as unwilling hosts to wave after wave of Anatolian yokels seems to them like a cruel ending after the leadership that the Kemalists once benevolently exercised over the country. These same urban Turks participated in the huge antigovernment protests of the spring. Combined with the actions and statements of the armed forces, secular groups, and President Sezer, their openly expressed concerns about Islamism contributed to the impression that a very large coalition was forming.

The coalition turned out to be smaller, and less able to rally other Turks, than the protests suggested. One reason for this is that for all their rhetorical defense of “modernity,” the Kemalists have a limited program, founded on paranoia and opposition to change. The leader of the CHP, for instance, the party that Atatürk founded, has claimed to be the target of a CIA assassination plot. During the election campaign, the newspaper Cumhuriyet, a bastion of the Kemalist left, competed with far-right publications in its chauvinistic denunciation of such institutions as the IMF and the EU.

Yasar Büyükanit, the chief of the armed forces, is deeply skeptical about the European Union. He has hinted that the EU is trying to dismember Turkey by supporting Kurdish nationalists and other minorities, and by demanding a formal recognition by the Turkish government of the 1915 Armenian massacres. In 2005, while Büyükanit was head of Turkey’s land forces, he aroused concern in Europe by praising a military agent who had been arrested after bombing a bookshop owned by a Kurdish nationalist. Immediately after Gül’s election, he warned that “crafty plans” were being hatched to “destroy the gains of modernity.” This was interpreted as an allusion to a new constitution, currently being drafted behind closed doors, which Erdogan has proposed to adopt next year. This document is expected to subordinate further the armed forces to civilian authority, and to give the Kurds unprecedented cultural recognition—reforms that the European Union has long advocated.3

There is a consensus among many Turks, and among Europeans friendly to Turkey, that the Kemalist elite must continue to give up power. At the same time, even Turkey’s small number of genuine liberals grudgingly appreciate that were it not for the armed forces and some judges, the Islamists might not have moderated their message or their policies to the extent that they have. Had the armed forces not intervened in 1997, and the courts not banned the Welfare Party and jailed Erdogan, Turkey’s political life would indeed have become more Islamist in character. While many distrust the Islamists’ actions, innocuous as they are, it is the intentions and sincerity of Erdogan and Gül that are the real source of anxiety—and which the armed forces use to justify their continuing involvement in public life.

Many pro-EU Turks link their country’s future development to its joining the European Union. According to this view, membership would prevent the resurgence of radical Islamism and force the armed forces to assume the diminished powers, accountable to elected civilians, that they have in other EU countries. But entry into the EU, in spite of the AKP’s recent pledge to redouble its efforts to meet the EU’s criteria, seems a long way off. Since 2006, negotiations have been frozen on several of the “chapters” of EU law that countries must adopt in order to be admitted, and which would require the Turks to make further improvements in human rights and to promote the cultural rights of minorities such as the Kurds. In part this freeze is punishment for Turkey’s refusal to open its ports to Greek Cypriot ships unless the EU lifts its thirty-three-year-old trade embargo on the Turkish-run northern third of the island, a self-styled republic that the EU does not recognize. It is also a response to Turkey’s shortcomings in other matters, including human rights. The EU leaders are particularly unhappy about the AKP’s failure to scrap a notorious article of the penal code under which several people, including the 2006 Nobel laureate for literature, Orhan Pamuk, have been charged with “insulting Turkishness,”4 often because they denounce Turkey’s massacre of Armenians in 1915.

Mutual hostility between Turks and some countries in the European Union has risen in recent years. According to a recent poll conducted by the German Marshall Fund of the United States and the Compagnia di San Paolo, an Italian foundation, 49 percent of people in France, and 43 percent of people in Germany, where there is widespread hostility toward the country’s large number of immigrant Turks, regard the prospect of Turkish membership as a “bad thing,” while a mere 40 percent of Turks support membership in the union—a big drop from the 73-percent figure for 2004. Turks’ enthusiasm for the union seems to have fallen in proportion to their declining confidence that they will be admitted. According to the same survey, barely a quarter of Turks expect the union to let them in. Since coming to power, Nicolas Sarkozy has said that he may not carry out his campaign pledge to block accession negotiations on further “chapters,” but he continues to favor a “privileged partnership” for Turkey, not full membership.

The irony is that in Abdullah Gül Turkey finally has a president who is an avowed Europhile and an advocate of human rights and other European ideals. It is possible that the AKP, emboldened by its second mandate, may do what Ali Babacan, the new foreign minister, recently said it would, which is to accelerate the reform process and promulgate a new constitution, “to prepare a better…environment for our own people,” so Turkey is “perceived more and more as an asset for the EU.” Equally, it is possible that some members of the government will revert, at least partially, to their former Islamist selves. On September 19, for instance, Erdogan announced that he wanted the new constitution to allow women to wear head scarves in universities. He described the issue as one of individual liberty.

In his inaugural address, President Gül defined secularism as “a rule for social peace no less than it is an empowering model for different ways of life within democracy.” This definition, with its suggestions of political and social pluralism, was seized on by some secularists in the press as fresh evidence that the government and the President are intent on dismantling the secular system in the name of increasing rights and, eventually, undermining democracy itself. That seems unlikely. Having identified the democratic process as an ally in their rise to power, many of Turkey’s mainstream Islamists have become convinced of its superiority to other systems of government. These men and women say they must face the challenge of reconciling Islam with a free politics. Whether they intended to or not, the Islamists have changed.

The AKP itself performed remarkably well on July 22. The party won 47 percent of the vote, 12 percent more than in 2002, but the entry into parliament of the far-right MHP, and some independents, meant that it got slightly fewer seats, 341 of the 550 available.

The election was not a contest between Islamism and secularism. Although the antigovernment protests of the spring were impressive, they were held in relatively progressive parts of western Turkey, underscoring the absence of large numbers of passionate secularists in central and eastern Anatolia. The largely secular CHP campaigned on issues such as corruption, the lot of the poor, and the government’s handling of the Kurdish problem. The MHP taunted the government for not hanging Abdullah Öcalan, the incarcerated leader of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), whose long, ongoing war against the Turkish state has so far cost around 37,000 lives. The CHP won ninety-nine seats, the MHP seventy-one.

The AKP has become Turkey’s first party in decades to have support from all parts of Turkey. This was illustrated by its impressive showing in the eastern and southeastern provinces whose inhabitants are mostly Kurdish—provinces that have given a great deal, in lives, suffering, and perennial underdevelopment, for Öcalan and his cause.

On election night I was in the headquarters of the Democratic Society Party, Turkey’s latest Kurdish nationalist party, in Varto, a rural district in the mainly Kurdish province of Musåü. The party had nominated some of its leading members as independent candidates, hoping to circumvent an electoral rule preventing small parties from entering parliament, and there was at first much optimistic talk in the room. But the results were extremely disappointing. In a district that has provided the PKK with hundreds of recruits, the AKP vote rose at the expense of the Kurdish nationalists. And the electoral strength of the AKP generally came as a shock. The party won more than 50 percent of the vote in several overwhelmingly Kurdish provinces.

The AKP has used its power cannily in the Kurdish provinces, extending free health care and giving out schoolbooks as part of a campaign to persuade people in the partly illiterate region to send their children to school. The AKP’s reputation for piety has not harmed it since many Kurds, despite the PKK’s disapproving attitude toward religion, are pious as well. The Kurds appreciate the government’s resistance to pressure from the armed forces to authorize an attack across the border into northern Iraq on PKK camps there.5 But the main explanation for the AKP’s popularity among the Kurds is that Erdogan, unlike his predecessors, recognizes that the Kurdish problem turns on respect for Kurdish ethnic identity, not economic and social backwardness. The government has modestly increased the Kurds’ linguistic and cultural autonomy and much reduced torture in police stations, a major change. The fighting, although it continues, is less intense than it was.

The new constitution will allow, so some have said, the teaching of Kurdish as a second language in Turkish schools. It will also redefine Turkish citizenship without any reference to ethnicity. Such reforms would be popular among the Kurds, who resent the current constitution’s emphasis on Turkish culture. The PKK, which has stopped demanding a separate Kurdish state, could hardly complain.

A danger for the future is that as the PKK watches the AKP gain popularity in the southeast, it may intensify its attacks on the security forces, hoping that the reaction will radicalize normal Kurds, who are mostly fed up with war. Another danger is that the Turkish army could decide to intensify the war against the PKK. That would strike another blow at Turkey’s already frustrated European aspirations.

A third danger is that Erdogan and his allies will recklessly allow some of their old Islamist instincts to reassert themselves. There is little doubt that, if Erdogan insists on reversing the ban on head-scarved women in universities, there will be another crisis. It would be a mistake for the AKP to assume brazenly that the age of coups is over. On balance, however, Turkey gives ground for hope. It is possible that an Islamist movement with a history of intolerance and bigotry will succeed in transforming Turkish politics along genuinely democratic lines. This seems to be the task that the AKP has set itself; with what degree of determination, time will tell. The 2007 general election, as much a triumph for democracy as it was for the AKP, may one day be seen as a turning point.

—September 27, 2007

This Issue

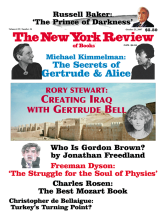

October 25, 2007

-

1

See the European Stability Initiative’s “Sex and Power in Turkey: Feminism, Islam and the Maturing of Turkish Democracy” (Berlin and Istanbul: ESI, June 2, 2007), available at www.esiweb.org. ↩

-

2

See Islamic Calvinists: Change and Conservatism in Central Anatolia (Berlin and Istanbul: ESI, September 19, 2005), available at www.esiweb.org. A recent comparative study by the Türkiye Ekonomik ve Sosyal Etüdler Vakf? (Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation), an Istanbul think tank, supports the contention that Turks generally are becoming more moderate as well as more religious. In 1999, the study found, 86 percent of respondents expressed some degree of religiosity; in 2006 the figure was 93 percent. Over the same period, the percentage of respondents opposed to the setting up of a religious state went up from 68 percent to 76 percent. ↩

-

3

It should not be assumed that the armed forces are the generally disinterested Europhiles described in Foreign Affairs last year (see Ersel Ayd?nl?, Nihat Ali Özcan, and Dogan Akyaz, “The Turkish Military’s March Toward Europe,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2006). The authors are informative on the AKP’s trimming of military powers and privileges, but they are excessively optimistic when they suggest that the armed forces want Turkey to join the EU and believe that membership could solve the problems of Kurdish nationalism and rising Islamism. My impression is that General Büyükan?t and other senior officers fear that membership will exacerbate these problems and challenge Turkish sovereignty. Junior officers are, if anything, even blunter than Büyükan?t in their hostility to the EU. ↩

-

4

Criticism is not restricted to Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code, which has been used to prosecute Pamuk and other writers: see Amnesty International’s recent report on abuses in the Turkish justice system, “Justice Delayed and Denied: The Persistence of Protracted and Unfair Trials for Those Charged under Anti-terrorism Legislation.” ↩

-

5

The government, it is reported, believes that an incursion by the Turkish army would harm relations with the US and, to a lesser extent, the EU. Erdogan, for his part, is said to want a peaceful resolution to the conflict. ↩