The ruins of a Russian Orthodox monastery, 1939: paint peels from the walls, light filters in from the cracks in the ceiling, cigarette smoke whirls through the air. Primitive wooden camp beds are stacked up high, one on top of the other, for the monastery has been turned into a prison. The prisoners, soldiers in khaki-brown wool uniforms and black boots, are gathered in a large group. Craning their heads forward, they listen to their commanding officer make a speech. Solemn and tired, he does not ask them to fight. He asks them to survive. “Gentlemen,” says the general, “you must endure. Without you, there will be no free Poland.”

The scene ends. The audience—at least the audience in the Warsaw theater where I watched the film—sighs, rustles, collectively draws its breath. Those watching know, as they were meant to know, that the soldiers, the flower of Poland’s pre-war officer corps, did not survive. And without them, there was indeed no free Poland.

In its way, this episode—both the action on screen and the audience reaction in the theater—represents the quintessence of the art of its director, Andrzej Wajda. For half a century, beginning in the darkest era of communism and continuing through the years of Solidarity, martial law, and the post-Communist present, Wajda has been conducting precisely this kind of cinematic dialogue with Polish audiences. Although they have sometimes been celebrated abroad, his movies have always been made with his countrymen in mind, which gives them a special flavor. Because he knows what his Polish viewers will know—about history, about politics, about the ways people behave under occupation—Wajda has always been able to rely upon them to interpret his work correctly, even when censorship forced him to make his points indirectly. His latest film, Katyn, in which the scene described above appears, is in this sense a classic Wajda movie.

Certainly its Polish viewers know how it will end, long before they enter the cinema. Katyn, as its title suggests, tells the story of the near-simultaneous Soviet and German invasions of Poland in September 1939, and the Red Army’s subsequent capture, imprisonment, and murder of some 20,000 Polish officers in the forests near the Russian village of Katyn and elsewhere, among them Wajda’s father. The justification for the murder was straightforward. These were Poland’s best-educated and most patriotic soldiers. Many were reservists who as civilians worked as doctors, lawyers, university lecturers, and merchants. They were the intellectual elite who could obstruct the Soviet Union’s plans to absorb and “Sovietize” Poland’s eastern territories. On the advice of his secret police chief, Lavrenty Beria, Stalin ordered them executed.

But the film is about more than the mass murder itself. For decades after it took place, the Katyn massacre was an absolutely forbidden topic in Poland, and therefore the source of a profound, enduring mistrust between the Poles and their Soviet conquerors. Officially, the Soviet Union blamed the murder on the Germans, who discovered one of the mass graves (there were at least three) following the Nazi invasion of Russia in 1941. Soviet prosecutors even repeated this blatant falsehood during the Nuremberg trials and it was echoed by, among others, the British government.

Unofficially, the mass execution was widely assumed to have been committed by the Soviet Union. In Poland, the very word “Katyn” thus evokes not just the murder but the many Soviet falsehoods surrounding the history of World War II and the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939. Katyn wasn’t a single wartime event, but a series of lies and distortions, told over decades, designed to disguise the reality of the Soviet postwar occupation and Poland’s loss of sovereignty.

Wajda’s movie, as his Polish audiences will immediately understand, is very much the story of “Katyn” in this broader sense. Its opening scene, which Wajda has said he has had in his head for many years, shows a group of refugees heading east, crossing a bridge, fleeing the Wehrmacht.1 On the bridge, they encounter another group of refugees heading west, fleeing the Red Army. “People, where are you going, turn back!” the two groups shout at one another. Soon afterward, Wajda shows Nazi and Soviet officers conversing in a comradely manner along the new German–Soviet borders—as surely they did between 1939, the year they agreed to divide Central Europe between them, and 1941, when Hitler changed his mind about his alliance with Stalin and invaded the USSR. On the bridge, Poland’s existential dilemma—trapped between two totalitarian states—is thus given dramatic form.

Within the notion of “Katyn,” Wajda also includes the story of the father of one of the officers, a professor at the Jagellonian University in Kraków. Asked to attend a meeting by the city’s Nazi leadership, he joins other senior faculty in one of the university’s medieval lecture halls. Instead of holding a discussion, Nazi troops enter, slam the doors, and arrest everyone in the room. The men, many elderly, are forced onto trucks, the officer’s father among them. Later, his widow will learn that he died, along with many of his colleagues, in Sachsenhausen. Some have cited this scene, which is not directly related to the Katyn massacre, as an example of how Wajda tried to put too many themes into a single film. Wajda himself explains elsewhere that he sees it as part of the same story, since this Sonderaktion in Kraków was the German equivalent of the Katyn massacre: an open attack on the Polish intelligentsia, an attempt to destroy the nation’s present and future leadership.2

Advertisement

Other stories follow, at a rapid clip. Stories of the wives left behind, many of whom, like Wajda’s mother, didn’t know the fate of their husbands for decades; stories of the men who survived Soviet deportation, and were consumed by guilt; stories of those who tried to accept and adjust to the lie and move on. The film ends with a stunningly brutal, almost unwatchable depiction of the massacre itself. Wajda increases the horror by focusing on the terrible logistics of the murder, which took several weeks and required dozens of people to carry out: the black trucks carrying men from the prison camps to the forest, the enormous ditches, the rounds of ammunition, the bulldozers that pushed dirt onto the mass graves.

Along the way, Wajda also tells stories that echo episodes in his earlier films and in his own life—as, once again, he knows, his Polish audience will understand. At one point, one of his characters, Tadeusz, the son of a Katyn victim and a former partisan who has spent the war in the forests—files an application to return to his studies. Like Wajda himself at that age, he wants to attend the School of Fine Arts. Told he will have to erase the phrase “father murdered by the Soviets in Katyn” from his biography, Tadeusz refuses, runs out, and tears a pro-Soviet poster down in the street outside. Minutes later, he is discovered and shot in the street by Communist soldiers. Like the hero of Wajda’s 1958 film Ashes and Diamonds, he dies a pointless, postwar death, fighting for a failed cause. But unlike that earlier hero—created for a more cautious and more heavily censored time—he feels no ambivalence about that cause. Unlike Wajda himself, Tadeusz prefers death and truth to a life lived in the shadow of historical falsehood.

To anyone unacquainted with Polish history, some of these stories will seem incomplete, even confusing. Characters appear, disappear, and then appear again, sometimes so briefly that they are hardly more than caricatures. Some of them, most notably the sister who plays the part of a modern Antigone, determined to erect a gravestone to her lost brother, are so laden with symbolism that they don’t feel very realistic. Dialogues are brief, uninformative. Scenes shift from Kraków to Katyn, from the Russian- to the German-occupied zone of Poland. References are made to people and places that are significant to Poles but that will be obscure to everybody else, a phenomenon that helps explain why the film has not, to date, found an English-language distributor. But then, English-language distribution wasn’t one of Wajda’s concerns. This film wasn’t made for the benefit of those who are unacquainted with Polish history.

Since the late 1980s, it has been possible to talk openly about the Katyn massacres in Poland and Russia. Since 1990, when Mikhail Gorbachev first acknowledged Soviet responsibility for Katyn, and 1991, when Boris Yeltsin made public the documents ordering the massacre, it has even been possible to research them in Russian archives. Academic and popular history books on the massacre have now been published in several languages, including Russian.3 Yale University Press has now translated the most important documents into English, and published them with extensive annotation, background information, and rare photographs, including one taken from a German airplane in 1943.4 The Polish government has constructed multiple memorial sites, in Warsaw as well as in the Katyn forest itself. When his film came out last fall—on September 17, the sixty-eighth anniversary of the Soviet invasion of Poland—Wajda was asked several times to explain himself. Why Katyn? Why now? One interviewer put it rather brutally: “I didn’t feel a deep need to watch a film about Katyn—why would I? It seems that everything on that subject has already been said.”5

Wajda answered these questions in various ways, depending on how they were asked—it was only recently, he said, that he came up with a script he liked, though he has wanted to make a movie about Katyn for decades—but his most striking explanations involved his audience. Most of those who actually remembered the events of 1939 were now dead, he explained—Wajda himself is eighty-one—so the film could no longer be made for them. Instead, he said, he wanted to tell the story again for young people—but not just any young people. Wajda said he wanted to reach “those moviegoers for whom it matters that we are a society, and not just an accidental crowd.”

Advertisement

In an era when Hollywood dialogue is sometimes deliberately simplified in order to be easily subtitled, when the definition of a “successful” movie is one that makes money in many countries, and when many movies are “niche marketed” to appeal to some groups and not others, this explanation struck me as rather remarkable. There is something deeply old-fashioned about the idea that movies can help create strong, positive bonds of patriotism among strangers. Certainly it’s a notion alien to contemporary American audiences. If movies ever helped bind us together as a nation, the way Walter Cronkite once bound us together by interpreting the evening news, it’s hard to see how they do any longer.

It’s true that the notion of a national cinema comes more naturally to smaller, non-English-speaking nations, who are accustomed to talking among themselves without others listening. Still, when most Europeans call for a national cinema, they usually do so in a different manner. In France, movies are yet another tool in the great competition for international influence. Other countries consider their film industries in much the same light as their national airlines: a matter of prestige, albeit one in heavy need of government subsidy.

But both in the interviews he’s given and in the film itself, Wajda seems to be saying something rather different about the need for a national cinema. By making Katyn, he wanted to create something that would get Poles to talk to one another, to reflect upon common experiences, to define common values, to admire similar virtues, to forge a civil society out of an anonymous crowd. Katyn is deliberately intended to inspire patriotism, in the most positive sense of the word. This too helps explain why Wajda made a film that asks not just “what happened?” or “what did the Soviet Union do to us?” but rather “how did we, as a society, react afterward?” as well as “and how do we remember it now?”

At least judging by the initial reactions, Wajda seems to have succeeded, at least in getting the conversation started. The premiere of Katyn took place at the National Opera in Warsaw, and was covered live by all the important national newspapers and television stations. In attendance were the Polish president and first lady, the prime minister, the Catholic primate, Lech Wal/e?sa, assorted historians, novelists, composers, and victims’ families, as well as the film stars who more normally go to that sort of event. For a few weeks, almost every cinema in the country was showing the film, sometimes a dozen times a day. After only a month, more than two million people had been to see it—a large percentage in a country of 39 million—and the film is already among the top ten best-attended of the past decade. Every newspaper and magazine reviewed it, sometimes in special supplements.

More to the point, everybody talked about it, even if not everybody liked it. “Have you been to see Katyn yet?” was something one was asked with some frequency in Warsaw this past fall. The question sparked a dozen discussions—about Wajda’s earlier films, about the factual elements of the movie, about Russia—that would not have taken place otherwise.

But there are also pitfalls inherent in trying to make patriotic movies and Wajda, sometimes through no fault of his own, ran into a few of them. Purely by accident, Katyn was premiered in the middle of an unexpectedly early Polish parliamentary election campaign. Partly as a result, the leaders of the political party then in power—officially named Law and Justice, better known as the party of the identical Kaczynski twins—was accused of attempting to manipulate the nation’s sudden interest in Katyn for its own purposes. With no more than a couple of weeks’ notice, the government suddenly decided it would hold a major Katyn commemorative ceremony, with several elected officials given starring roles, as if the legacy of Katyn belonged to their political party and not any other. The Katyn families protested, as did Wajda. The date of the ceremony was changed. But the ugly image—of politicians vying to take advantage of the emotions raised by the movie—stuck.

Not surprisingly, given that bitterness over Katyn has undermined Polish– Russian relations for more than six decades, Wajda’s film also provoked a few nasty outbursts in Poland about Russians, and vice versa. In an interview with Izvestiya, Wajda himself tried to stave off this battle before it began: “In Poland there has always been great sympathy for the Russian people,” he said. “We make distinctions between the people and the system.”6 Some Russians took Wajda at his word. The Russian democrat, human rights activist, and ex-dissident Sergei Kovalev, who attended a showing of the film at the Polish embassy in Moscow, afterward called on Poles to “forgive us” for the murder.

But although there was no official Russian government reaction, on the day after the film’s release, a government-owned Russian newspaper, Rossiiskaya Gazeta, declared that Soviet responsibility for Katyn was “not obvious.” In a snide article, one of the newspaper’s pundits threw doubt on a decade’s worth of voluminous archival publications, and accused Wajda of “separating us further from the truth.”7 The article implied that Mikhail Gorbachev’s acknowledgment of Soviet responsibility for Katyn had been purely political, a dubious statement made to please the West. Quotes from the article were reprinted throughout Poland—sometimes accompanied by reprints of the documents ordering the massacre—and taken as evidence that not much in Russia has changed since 1939.

Following that piece of nastiness, perhaps it is not surprising that a few days later, Polish commentators took offense at the fact that Katyn was not a contender at the Venice film festival. Some wondered darkly whether this was a reflection of secret Russian influence over the jurors; others took it as yet another sign that foreigners don’t understand Polish history, or don’t appreciate Polish suffering, or otherwise discriminate against Poland. In fact, Katyn simply appeared too late to make the festival’s cut-off date, and will probably be shown in Venice next year. But for a day or two, before this technical explanation became clear, the nation’s insecurities were on sudden, prominent display.

That these feelings appeared is not surprising: they are in fact very typical side effects, not just of patriotic cinema but of patriotism itself. The same emotions that bind people together—inspiring them to work toward common goals, build political institutions, try to make their societies free and fair—are in some sense related to the emotions that make the same people paranoid about foreigners, or distrustful of the unpatriotic people who live down the street and vote for a different political party. Too much patriotism can hamper democracy and diminish civil society. On the other hand, without some patriotism, democracy is not possible at all.

The real test of Katyn, of course, is whether it remains a part of the Polish national conversation over time, as a handful of Wajda’s earlier films have indeed done. This is not just a question of the film’s quality. Its endurance will also depend on the continued existence of an audience that shares Wajda’s knowledge of twentieth-century Polish history, and that understands the symbols and shortcuts he uses to evoke his national and patriotic themes. Fifty years after it was made, a significant number of Poles still know that when the two young men in Ashes and Diamonds start listing names, setting a glass of alcohol alight for each one, they are talking about friends who died in the wartime underground and the Warsaw uprising, even if they never say so. If, fifty years from now, there is still an audience in Poland that understands Wajda’s characters and references—an audience that intuitively draws its breath when the general tells his men that without them “there will be no free Poland”—then Katyn, the movie, will still matter.

This Issue

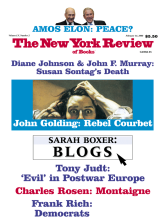

February 14, 2008

-

1

Andrzej Wajda, Katyn (Warsaw: Prószynski i S-ka, 2007), p. 6. This annotated edition of the screenplay includes Wajda’s commentary and letters, as well as photographs, maps, a historical timeline, and original documentation provided by the families of the Katyn victims. ↩

-

2

Wajda, Katyn, p. 24. ↩

-

3

Among the post-1990 books on Katyn are Natalia Lebedeva’s Katyn: Prestuplenie protiv chelovechstva (Moscow: Kultura, 1994), the first documented account in Russian; and Katyn: Plenniki neob’iavelnnoi voiny, a collection of Soviet archival documents, edited by R.G. Pikhoia et al. (Moscow: Mezhdunarodnyi Fond Demokratiia, 1997). An expanded version of the latter was also published in a four-volume Polish edition as Katyn: Dokumenty Zbrodni (Warsaw: Trio, 1995–2006) under the supervision of the Polish National Archives. In English, Allen Paul’s Katyn: Stalin’s Massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection (Naval Institute Press, 1996) also uses archival sources. ↩

-

4

Katyn: A Crime Without Punishment, edited by Anna M. Cienciala, Natalia S. Lebedeva, and Wojciech Materski (Yale University Press, 2008). ↩

-

5

Tadeusz Sobolewski, “Tylko guziki nieuginte,” Gazeta Wyborcza, September 17, 2007. See also “Przesznosc nieopowiedziana,” Tygodnik Powszechny, September 18, 2007. ↩

-

6

Vita Ramm, “Pravda pana Vaidy,” Izvestiya, September 18, 2007. ↩

-

7

Alexander Sabov, “Zemlya dla Katyn: Komentarii,” Rossiiskaya Gazeta, September 18, 2007. ↩