The reputation of Irène Némirovsky, in the English-speaking world as in France, rests on Suite Française, an unfinished multipart novel that appeared in print only in 2004, some sixty years after its author’s death. During her lifetime Némirovsky was best known for an early work, the novel David Golder (1929). Astutely promoted by its publisher and swiftly adapted for stage and screen, David Golder was a runaway commercial success.

Némirovsky never struck it quite as rich in the rest of her short career (she died at the age of thirty-nine, one of the victims of the Final Solution). She wrote a great deal, her books sold well, but in an age when experimental Modernism held the high ground she received little serious critical attention. After the war she slid into obscurity. When in 1978 Germaine Brée published her authoritative survey of French literature of the half-century 1920–1970, Némirovsky did not figure in the list of her top 173 writers (nor, however, did Colette, who would today be among many critics’ top ten). Even feminist critics paid her scant attention.

All of that changed when Suite Française—which by amazing good luck survived the war in manuscript—was finally published. Against all precedent, Némirovsky was awarded the Prix Renaudot posthumously. Suite Française became both a critical success and a best seller. Hastily her publishers began reprinting her oeuvre.

With its large cast of characters and wide social range, Suite Française is more ambitious than anything Némirovsky had previously attempted. In it she takes a hard look at France during the Blitzkrieg and the subsequent occupation. She saw herself as following in the line of Chekhov, who had addressed the “mediocrity” of his times “without anger and without disgust, but with the pity it deserved.” In preparation for her task she also reread War and Peace, studying Tolstoy’s method of rendering history indirectly, through the eyes of his characters.

Of the four or five novels of the planned Suite, only the first two were written. At the center of the second is a young woman, Lucile Angellier, whose husband is a prisoner of war and who has to share her home with a Wehrmacht officer billeted with her. The officer, Lieutenant von Valk, falls deeply and respectfully in love with her, and she is tempted to respond. Can she and he, nominal enemies, not transcend their political and national differences and, in the name of love, make a separate peace? Must she really, in the name of patriotism, deny herself to him?

Today it may seem puzzling that a writer confronting the crisis for the individual conscience occasioned by the occupation and the wider war should have framed that crisis in such romantic terms. For the war in question was not just a matter of political differences spilling over onto the battlefield: it was a war of conquest and extermination aimed at wiping certain despised peoples from the face of the earth and enslaving others.

Genocide is of course not the enterprise von Valk signed up for. Lucile has even less of an inkling of Hitler’s ultimate goals. But that is hardly the point. Had Némirovsky appreciated how monstrous the conflict was in which France and Germany were embroiled, how different in essence it was from the wars of 1870 and 1914, she would surely, one thinks, have given herself a different plot to work with, one that would pivot on the question not of whether a separate peace was attainable between individuals but rather—for instance—of whether honorable German soldiers should not disobey the orders of their political masters, or of whether French civilians like Lucile should not be prepared to risk everything to save the Jews among them.

(Interestingly, Lucile does risk her life to save a fugitive, but that fugitive is not a Jew—there are no Jewish characters in Suite Française. As for von Valk, Némirovsky’s design was for him to die fighting on the Eastern Front.)

Unlike War and Peace, which, as Némirovsky notes in her diary, was written half a century after the event, Suite Française is written from “on the burning lava.” It was planned to cover the occupation from beginning to end. Its first two parts take us through mid-1941. What would happen next—in the novel as in the real world—Némirovsky could not of course foresee: in her diary she called it “God’s secret.” In regard to herself, God’s secret was that, in July of 1942, she would be arrested in her home by French police and passed on to the German authorities for deportation. Weeks later she would be dead of typhus in Auschwitz. In all, some 75,000 Jews would be shipped from France to the death camps, a third of them full French citizens.

Advertisement

Why did Irène Némirovsky and her husband—who certainly had the means to do so—not flee while there was time? Both born in Russia, they were, technically speaking, stateless persons residing in France, and therefore unusually vulnerable. Yet even when, in the mid-1930s, popular opinion began to harden against foreigners, and the anti-Semites on the French right, emboldened by events in Germany, began to beat their drums, the two did nothing to regularize their status. Only in 1938 did they exert themselves to obtain papers of naturalization (which, for whatever reason, were not issued) and go through the motions of renouncing the Judaic faith in favor of the Catholic.

After the defeat of 1940 they had an opportunity to relocate from Paris to Hendaye, a stone’s throw from the Spanish border. Instead they chose the village of Issy-l’Évêque in Burgundy, inside the German-administered zone. In Issy, as anti-Jewish measures began to bite (bank accounts of Jews were frozen, Jews were forbidden to publish, Jews had to wear the yellow star), the truth may have begun to dawn on them, though not the full truth (it was only in the winter of 1941–1942 that word began to filter down to the administrators in the conquered territories that the solution of “the Jewish Question” was to take the form of genocidal extermination). As late as the end of 1941, Némirovsky seems to have believed that whatever might befall the Jew in the street would not befall her. In a letter addressed to Marshal Pétain, head of the Vichy puppet government, she pleads that as a “respectable” ( honorable ) foreigner—as distinct from an “undesirable”—she deserves to be left in peace.

There are two broad reasons why Irène Némirovsky should have considered herself a special case. The first is that for most of her life it had been her heart’s desire to be French; and to be fully French, in a country with a long history of harboring political refugees but notably unreceptive to notions of cultural pluralism, meant being neither a Russian émigré who wrote in French nor a French-speaking Jew. At its most juvenile (see her partly autobiographical novel Le Vin de solitude ), her wish took the form of a fantasy of being reborn as a “real” Frenchwoman with a name like Jeanne Fournier. (Némirovsky’s youthful heroines are typically spurned by their mothers but cherished by more than motherly French governesses.)

The problem for Némirovsky as a budding writer in the 1920s was that aside from her facility in the French language, the capital she commanded on the French literary market con-sisted in a corpus of experience that branded her as foreign: daily life in pre-revolutionary Russia, pogroms and Cossack raids, the Revolution and the Civil War, plus to a lesser extent the shady world of international finance. In the course of her career she would thus alternate, according to her sense of the temper of the times, between two authorial selves, one pur sang French, one exotic. As a French authoress she would compose books about “real” French families written with an irreproachably French sensibility, books with no whiff of foreignness about them. The French self took over entirely after 1940, as publishers became more and more nervous about the presence of Jewish writers on their lists.

As for the exotic self, exploiting it required a careful balancing act. To avoid being labeled a Russian who wrote in French, she would keep her distance from Russian émigré society. To avoid being cast as a Jew, she would be ready to mock and caricature Jews. On the other hand, unlike such Russian-born contemporaries as Nathalie Sarraute (née Cherniak) and Henri Troyat (né Tarasov), she published under her Russian name, in its French form, until the wartime ban on Jewish writers led her to resort to a pseudonym.

The second reason why Némirovsky should have thought she would escape the fate of the Jews is that she had cultivated influential friends on the right, even the far right. In the months between her arrest and his own, these friends were the first people her husband contacted with pleas to intercede. To bolster her case he even scoured her books for anti-Semitic quotes. All of these friends let her down, mainly because they were powerless. They were powerless because, as it began to become clear, when the Nazis said All Jews with no exceptions they meant all Jews with no exceptions.

For her compromises with the anti-Semites—who, as the Dreyfus affair had made plain a half-century before, were fully as influential in France, at all levels of society, as in Germany—Némirovsky has recently had to undergo the most searching interrogation, notably by Jonathan Weiss in his biography of her.1 I do not propose to extend that interrogation here. Némirovsky made some serious mistakes and did not live long enough to correct them. Misreading the signs, she believed, until it was too late, that she could evade the express train of history bearing down on her. Of the large body of work she left behind, some can safely be forgotten, but a surprising amount is still of interest, not only for what it tells us about the evolution of a writer now in the process of being absorbed into the French canon but as the record of an engagement with the France of her day that is never less than intelligent and is sometimes damning.

Advertisement

Irène Némirovsky was born in Kiev in 1903. Her father was a banker with government connections. An only child, Irène had French governesses and spent summer vacations on the Côte d’Azur. When the Bolsheviks took power the Némirovskys moved to Paris, where Irène enrolled at the Sorbonne and dawdled for five years over a degree in literature, preferring partying to studying. In her free time she wrote stories. Interestingly, though Paris was the hub of international Modernism, the magazines to which she sent her work were conservative in their literary and political outlook. In 1926 she married a man from the same milieu (Russian Jewry, banking) as herself; they had two children.

For her first foray into the novel form Némirovsky drew heavily on her family background. David Golder is a financier and speculator with a special interest in Russian oil. Having begun his career in Russia buying scrap metal, he makes his mark supervising railroad crews in California. Now, in 1926, he owns an apartment in Paris and a villa in Biarritz. He is growing old, he has a heart problem, he would like to begin to retire. Behind him, however, flogging him on like a galley slave, are two women: a wife who despises him and flaunts her infidelity, and a daughter with expensive tastes in cars and men. When he has his first heart attack, his wife bribes the doctor to tell him it is not serious; when swings in the market bankrupt him, his daughter uses sexual wiles to get him to stagger out one last time to do battle in the boardrooms.

David Golder is a novel of stock characters and extravagant emotions, with a heavy debt to Balzac’s Le Père Goriot. Golder himself is a stereotypically unscrupulous wheeler-dealer. His wife is obsessed with her looks; his daughter is so locked into her round of pleasures that she barely sees her parents as human. But these crude materials undergo some development and modulation. Between Golder’s wife and her lover of many years—a parasitic minor aristocrat who may well be the daughter’s natural father—there are moments of near-domestic affection. The daughter is allowed a chapter of lyrical sex and gastronomy in Spain to persuade us of her claim that pleasure is a good in itself. And beneath the features of the titan financier we get to see first the mortal man frightened of death, then the little boy from the shtetl.

The last pages of David Golder are as affecting as anything Némirovsky wrote. Sick and dying, barely able to draw breath, Golder boards a tramp steamer at a Black Sea port and takes to his bunk. There he is tended by a young Jew with his own dreams of getting to America and making his fortune. As he dies, Golder drops the masks of the French and Russian languages and returns to the Yiddish of his childhood; in his last vision he hears a voice calling him home.

There is plenty of anti-Semitic caricature in David Golder. Even the end of the novel can comfortably be accommodated to the worldview of the anti-Semite: beneath a veneer of cosmopolitanism Golder’s deepest loyalties turn out after all to be archaic and Jewish. In an interview given in 1935 Némirovsky conceded that if Hitler had been in power when she was writing the book she would have toned it down, “written it differently.” Yet considering its sympathy for the lonely and unloved Golder, battling on three fronts with ruthless competitors, predatory women, and a failing body, it is hard to see the book as at core anti- Semitic. Némirovsky seems to have felt so too: in the interview she goes on to say that to have toned it down at the time—that is, without an adequate political motive—would have been wrong, “a weakness unworthy of a true writer!”

On the back of the success of David Golder in its various incarnations Némirovsky built a prosperous career as a woman of letters. At her peak she was bringing in considerably more money than her husband, an executive with the Banque des Pays du Nord. The couple kept a spacious apartment in Paris with domestic staff (maid, cook, governess); they took vacations at fashionable resorts. Their lifestyle became unsustainable once restrictions on Jews participating in the economy came into effect. By the time they were deported in 1942, the Némirovskys were in dire financial straits.

David Golder comes to us now in a collection with three other short works from Némirovsky’s early phase: The Ball (1930), Snow in Autumn (1931), and The Courilof Affair (1933). Claire Messud provides a perceptive introduction; Sandra Smith’s translations are of the highest quality, though the decision to give Russian names in their French forms is puzzling: Pobiedonostsef, Tcheka instead of Pobedonostsev, Cheka.

The Ball is a slighter affair than David Golder. M. and Mme Alfred Kampf, petit-bourgeois arrivistes who have made a fortune on the stock market, decide to come out in Paris high society. They plan a ball, no expenses spared, for which they draw up a list of two hundred fashionable invitees. To their unloved daughter Antoinette falls the task of mailing the invitations. But Antoinette, full of resentment against her mother for refusing to let her appear at the ball, secretly tears up the invitations. The great night comes and no guests arrive. With grim pleasure Antoinette watches as her parents, humiliated in front of the servants, go to pieces. In the last scene she pretends to console her weeping mother, while inwardly reveling in her victory.

The inimical mother-daughter couple recurs often in Némirovsky’s fiction, the mother determined to repress at all costs the daughter who, by emerging into womanhood, threatens to overshadow and supersede her. It is perhaps Némirovsky’s most telling weakness as a writer that she is unable to do anything with this material beyond reproducing it again and again.

Snow in Autumn, retitled from the French Les Mouches d’automne (The Flies of Autumn), and not to be confused with the as yet untranslated Les Feux de l’automne (The Fires of Autumn), follows the declining years of Tatiana, faithful nanny to the Karines, a wealthy Russian family forced to abandon their estate during the Civil War and make their home in France. As time passes, it is Tatiana who emerges as the principal victim of the Revolution rather than the Karines, who have managed to smuggle out a considerable fortune and have adapted to life abroad rather easily. Tatiana, by contrast, unable to make sense of France, yearns for the country estate where she grew up and for the snows of Russia. More and more neglected by the Karines, her mind wandering, she leaves the apartment one foggy morning and is drowned, or drowns herself, in the Seine.

Snow in Autumn owes a general debt to Chekhov and a specific debt to A Simple Heart, Flaubert’s coolly factual story of a similarly faithful retainer. Aside from the arbitrary ending—Némirovsky’s endings tend to be cursory, perhaps a consequence of her habit of starting a new project before the old one was properly finished—it is an accomplished piece of work, opposing Russian provincial life and old-fashioned fidelities, embodied in Tatiana, to Paris and the new, casual sexual mores that the younger Karines find so attractive.

The Courilof Affair takes the form of a memoir written by a member of a terrorist cell, telling of how, shortly before the failed 1905 revolution, he infiltrated the staff of Count Courilof, the Tsar’s minister of education, with the object of carrying out a spectacular assassination. Posing as a Swiss doctor, he becomes the intimate observer of Courilof’s struggle with on the one hand liver cancer, on the other political rivals who are using his marriage to a woman with a dubious past to engineer his downfall.

Slowly the would-be assassin begins to appreciate the better qualities of his victim: his stoicism, his refusal to distance himself from the wife he loves. When the time comes to hurl the bomb, he cannot do it: a comrade has to take over. Arrested and sentenced to death, he escapes across the border, returning later to enjoy a career in the Soviet secret police during which he tortures and executes enemies of the state without compunction, before being purged and exiled to France, where he pens his memoir.

Redolent of the Conrad of Under Western Eyes, The Courilof Affair is Némirovsky’s most overtly political novel. (Conrad, the anglicized Pole, impressed Némirovsky as a model of successful acculturation.) The central plot device—a foreigner with fake medical papers becomes the confidant of one of the most powerful men in Russia—may be implausible, but it pays off handsomely. The gradual humanization of an assassin brought up in the most blinkered of revolutionary circles is masterfully done: Némirovsky allows herself all the space she needs to trace his erratic moral evolution. Courilof emerges as something like a hero, a complex man, severe but incorruptible, touchingly vain, devoted to the service of a sovereign whom he personally despises. For all his weaknesses, he stands for values that this ultimately elegiac book endorses: a cautious liberalism, the culture of the West.

With the publication of these four short fictions, English-speaking readers have access to the best of Némirovsky’s early writing to set beside her great, truncated novel of the war years. What we still lack is works from the phase 1939–1941, when she was trying to establish herself as an unambiguously French author, most notably the posthumously published Les Biens de ce monde (The Goods of This World), which traces the fortunes of a family of paper manufacturers in the years before and after World War I, and Les Feux de l’automne, which has at its center a woman coping with a wayward husband in the Paris of the interwar years. In both cases the milieu is impeccably French: no foreigners, no Jews.2

Both novels offer a diagnosis of the state of France. They blame France’s decline, culminating in the defeat of 1940, on political corruption, lax morals, and slavish imitation of American business practices. The rot set in, they suggest, when servicemen coming home from the trenches in 1919, instead of being given the task of reconstructing the nation, were fobbed off with easy sex and the lure of speculative riches. The virtues the books endorse are much the same as those promoted by the Vichy government: patriotism, fidelity, hard work, piety.

As works of art these two novels are unremarkable—part of Némirovsky’s aim in writing them was to show how well she fitted into the tradition of the family-fortunes novel exemplified by Roger Martin du Gard and Georges Duhamel. Their strengths lie elsewhere. They reveal how intimately Némirovsky knew ordinary petit-bourgeois Parisians—their domestic arrangements, their amusements, their little economies and extravagances, above all their placid satisfaction with the bonheur of their lives. Némirovsky was remote from the experiments in the novel form going on around her: of her American contemporaries, those she seems to appreciate most are Pearl Buck, James S. Cain, and Louis Bromfield, whose Monsoon she took as a model for the first part of Suite Française. As chronicles of the impact of wider forces on individual destinies, these most “French” of Némirovksy’s novels tend to be rather dutifully naturalistic.

The writing comes to life, however, when her interest in the psychology of moral compromise is engaged, as when the heroine of Les Feux de l’automne begins to have doubts about the celibate path she has been following. What if her women friends are right after all—what if chastity is démodé, what if she is going to be left on the shelf? With a sinking heart she dons her best outfit, fixes her face, and rings the doorbell of the man who has been pursuing her, ready to offer him her body if that is how relations between the sexes work in this new age. Fortunately for the book’s thesis—“the key to all existence [is that] one must be faithful”—the man in question has had second thoughts, and to win this paragon of virtue is now prepared to propose marriage.

In these two novels Némirovsky shows herself ready to take on traditionally masculine forms like battle narratives, where she acquits herself more than competently. She also composes lengthy set pieces about the evacuation of cities—clogged roads, cars piled high with household goods, quests for scarce gasoline, etc.—that in effect rehearse the powerful chapters opening Suite Française, in which defeated soldiers and panic-stricken city-dwellers flee the German advance. About the selfishness and cowardice of the civilian population in the face of danger she is scathing.

Both novels extend chronologically into the present of World War II and thus into the territory of the later Suite Française. Némirovsky clearly saw a role for herself as chronicler and commentator on unfolding events, even without knowing how the war would turn out. If we can extrapolate to the author from her characters, she would seem to stand behind Agnès, the most rock-solid figure in Les Biens de ce monde : “We will rebuild. We will fix things. We will live.” Wars come and go, but France endures. Vis-à-vis the German occupiers her approach is, understandably, ultra-cautious: they barely figure on her pages. Released after a year in a POW camp, a French serviceman breathes not a word against his captors.

The notebooks of Némirovsky’s last year disclose a far less sanguine view of the Germans, together with a hardening of her attitude toward the French: we may infer a degree of prudent self-censoring over the text of the Suite that has come down to us. They also reveal a foreboding that she will be read only posthumously.

Constructing herself as an unhyphenated French novelist was only half of Némirovsky’s life-project. As she was shoring up her French credentials she was also delving into her Russian Jewish past. Published in 1940 just before restrictions on Jewish authors came into effect, Les Chiens et les loups (The Dogs and the Wolves) has as its heroine Ada Stiller, a Jewish girl who grows up in the Ukraine but moves to Paris, where she lives from hand to mouth painting scenes of the world she has left behind, scenes too “Dostoevskian” in tone for French tastes. Complicated plotting involving wealthy relatives and financial skulduggery results in Ada being deported from France; the book ends with her facing a precarious future as an unwed mother somewhere in the Balkans.

At the heart of Les Chiens is the question of assimilation. Ada is torn between two men: Harry, the scion of a wealthy Russian-Jewish family, married to a French Gentile but drawn mystically to Ada; and Ben, a macher from the same shtetl as Ada, who believes she and he inherit a strain of “madness” that sets them apart from the “Cartesian” French. Which man should she follow? To which side does her heart incline: to the side of dogs like Harry, tame, assimilated, or that of wolves like Ben?

Sex plays no part in Ada’s decision-making. She is as asexual a heroine as could be. The inner voice that will tell her which future to choose, as dog or as wolf, will be the voice not of love but of her ancestors, the same voice heard by the dying David Golder. It will warn her that people like Harry, caught between two races ( sic ), Jewish and French, have no future. (Similarly, at a climactic moment in Suite Française, Lucile will feel “secret movements of [the] blood” that will tell her she cannot belong to a German.) Despite himself, Harry must concur: his assimilated self is a mask, but he cannot get rid of it without tearing his flesh.

We may want to bear in mind how matters stood in France at the time when Némirovsky was composing this most Jewish of her novels. On the eve of the war France’s Jewish population numbered some 330,000, most of them foreign-born. Initially the new arrivals had been welcomed—France had suffered huge losses of manpower in World War I—but after 1930, with the decline of the world economy, that welcome began to sour. The influx of a half-million refugees after Franco’s victory in Spain only hardened anti-immigrant sentiment.

The anti-Semitism that grew up in the 1880s and found its most vocal expression in the Dreyfus affair extended across the social spectrum and had several strands. One was the traditional anti-Judaism of the Catholic right. Another was the burgeoning pseudoscience of race. A third, hostility to “Jewish” plutocracy, became the province of the socialist left. Thus when popular resentment began to fester against refugees, Jewish refugees in particular, there was no substantial political group prepared to stand up in their defense.

France’s settled, secularized Jews, too, viewed with unease the flood of poor cousins from the East, adhering to their own language, dress, and cuisine, following their own rites, rife with excitable political factions. Spokesmen for French Jewry tried to warn the new arrivals that their unwillingness to fit in would give fresh impetus to the anti-Semites, but got nowhere. “The nightmare of old assimilated French Jewry had come true: what was perceived as an uncontrollable flood of exotic oriental Jews had compromised the position of them all,” write Michael Marrus and Robert Paxton in Vichy France and the Jews.3

The Judaic slant of Les Chiens et les loups—a more substantial, more ambitious, and less equivocal work than David Golder—thus comes as somewhat of a surprise, considering Némirovsky’s own assimilationist record and her comfortable place in French society. Partly as a result of happenstance but mainly because her secret soul tells her so, Némirovsky’s Ada Stiller opts not for the dogs of the fashionable suburbs but for the wolves from the East—the wolves from whom most dogs prefer to distance themselves, not wishing to be reminded of their origins.

Set mainly in Russia around the time of the revolution, published in 1935 but probably written earlier, Le Vin de solitude is a study in mother-daughter relations for which Némirovsky draws freely on her own life history. Hélène Karol is a gifted, precocious adolescent. Her father is a war profiteer, selling obsolete weaponry to the Russian government. Her mother, Bella, is a beautiful but depraved society hostess (“To hold in her arms a man whose name she did not know, or where he came from, a man who would never see her again—that alone gave her the intense frisson she craved”). Antagonistic to her daughter, Bella does all she can to undermine and humiliate her (a rerun of The Ball ). To revenge herself, Hélène sets out to steal her mother’s current lover. In doing so she strays into murkier and murkier moral territory. Lying in the man’s arms, she glances into a mirror and sees her own face, “voluptuous, triumphant, reminding her…of her mother’s features when she was young.” Troubled by this transformation, she dismisses him:

You are the enemy of all my childhood… Never will I be able to live happily with you. The man I want to live side by side with would never have known my mother, or my home, not even my language or my native country; he would take me far away, it doesn’t matter where.

Le Vin de solitude is part novel, part autobiographical fantasy, but mainly an indictment of a mother who casts her daughter in the role of sexual rival, thereby robbing her of her childhood and precipitating her too early into a world of adult passions. Jézabel (1936) is an even more lurid attack on the mother figure. Here a narcissistic socialite of a certain age, obsessed with her public image, purposely lets her nineteen-year-old daughter bleed to death in childbed rather than have it emerge that she has become a grandmother (years later the spurned grandchild will return to blackmail her). Books like Jézabel, dashed off in a hurry, offering sensationalistic glimpses into the lives of the fast set, make it easier to understand why Némirovsky was not taken seriously by the literary world of her day.

Némirovsky’s real-life mother was, by all accounts, not a nice person. When in 1945 her orphaned granddaughters, aged sixteen and eight, turned up on her doorstep, she refused them shelter (“There are sanatoriums for poor children,” she is reputed to have said). Nonetheless, it is a pity we will never hear her side of the story.

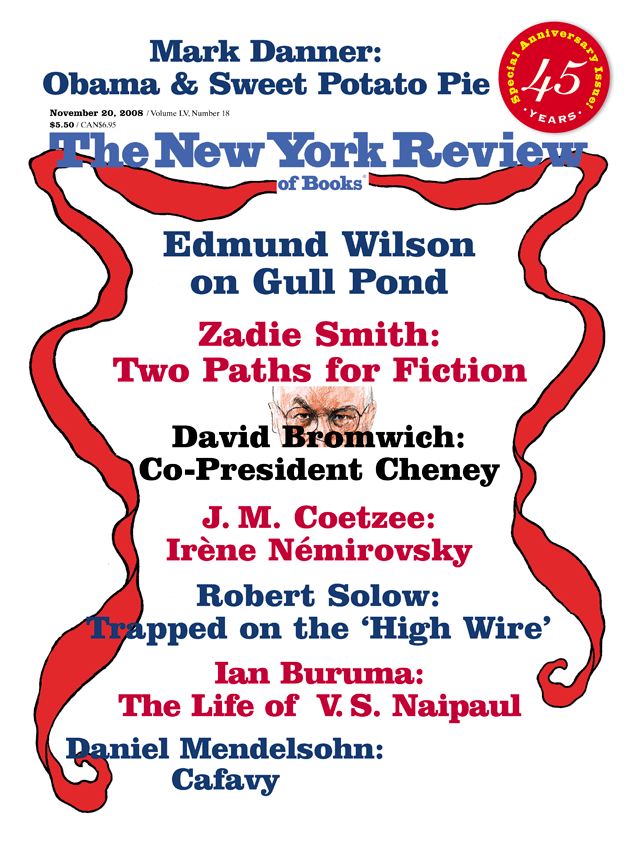

This Issue

November 20, 2008

The Co-President at Work

At Gull Pond

Two Paths for the Novel

-

1

Irène Némirovsky: Her Life and Works (Stanford University Press, 2007). A translation of the illuminating new biography by Olivier Philipponnat and Patrick Lienhardt ( La Vie d’Irène Némirovsky ), which draws heavily upon diaries and notebooks that have resurfaced in the last few years, is due to be published in the US by Knopf in 2009. ↩

-

2

Les Biens de ce monde, Le Vin de solitude, Les Chiens et les loups, and Jézabel are due to appear in Everyman’s Library in 2010 or 2011, in English translations by Sandra Smith. ↩

-

3

Basic Books, 1981, p. 366. ↩