Solzhenitsyn sent his letter to the Soviet leaders on September 5, 1973. Soon after he was deported from the USSR, it was published abroad,1 and excerpts were read over the radio. I believe it to be very important that this statement by an author of such indisputable world-wide prestige—a statement which he undoubtedly considered carefully and which reflects his essential views on many basic social questions—be subjected to serious analysis, especially by representatives of independent thought in our country. For me, it is doubly necessary to offer a critique of Solzhenitsyn’s letter because it contains several parallels to, and a covert debate with, certain of my previous statements on social questions—statements which I have since partially revised but which mostly still seem to me correct. But most of all, it is my disagreement with certain of the letter’s substantive ideas that compels me to speak out.

Solzhenitsyn is one of the pre-eminent writers and publicists of our day. The dramatic conflicts, striking images, and original language of his works convey his position—arrived at through much suffering—on the most important social, moral, and philosophical problems. Solzhenitsyn’s special and exceptional role in the spiritual history of our nation is associated with an uncompromising, accurate, and profound exposition of human misery and the crimes of the regime, crimes that were unprecedented in their harshness and secrecy. This role of Solzhenitsyn’s was already clearly evident in One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich; now it recurs in the great book The Gulag Archipelago, which I deeply respect. Whatever one’s attitude toward Solzhenitsyn’s positions, his own work must be regarded highly; and his influence will continue in the years ahead.

In his letter Solzhenitsyn again speaks of the sufferings and sacrifices which have been the fate of our people in the past sixty years. With particular conviction and a heavy heart he writes of the lot of women who, because of inadequate family budgets, must so often combine household duties and the bringing up of children with the heaviest kind of work to earn money; of the consequent deterioration in child rearing and the disintegration of the family; of the general drunkenness which has become a national scandal; of the theft, mismanagement, and featherbedding in government work; of the ruin of cities, villages, rivers, forests, and the soil. Like Solzhenitsyn, I consider those achievements which our propaganda so loves to boast about to be insignificant compared with the consequences of overstrain, disillusionment, and the depression of the human spirit.

However, even in the first part of Solzhenitsyn’s letter, which is devoted to critical fact-finding, there are certain peculiarities in his position which provoke in me uneasiness and a feeling of dissatisfaction, both of which are intensified with further reading. What strikes me in particular is that Solzhenitsyn singles out the sufferings and sacrifices of the Russian people. Of course everyone is entitled to write, and be concerned, about what he knows best—what disturbs him more personally, more concretely. And yet we all know that the horrors of the civil war, of “dekulakization,” of the famine, of the terror, of the Patriotic War,2 of the harsh repressions of those millions who returned from POW camps, of the persecution of believers—that all these things affected Russian and non-Russian subjects of the Soviet state to the same extent.

Such actions as forcible deportation and genocide, the fight against national liberation movements, and the suppression of national culture—these matters are essentially the “privilege” of non-Russians. Today we know that the schoolchildren of Uzbekistan, with whose progress the authorities are so fond of amazing foreign guests, must spend many months of every year on cotton plantations instead of studying, and that a great many of them are ill from inhaling herbicides. We must not forget all this in discussing such questions as Solzhenitsyn has raised. Nor should we forget that each people in our country has its share of historical guilt as well as a sense of participation in our positive achievements; and that in any event, their fates will be closely intertwined for a long time to come.

Solzhenitsyn proclaims that the chief dangers facing the nation are those of a war with China and of the contamination of the environment—the exhaustion of natural resources owing to excessive industrialization and urbanization. He regards both dangers as having been engendered by blind adherence to ideas imported from the West: to the dogma of unlimited scientific-technical progress (which he identifies with the unlimited quantitative expansion of large-scale industrial production), and in particular to Marxist dogma, which he regards as the embodiment of the antireligious lack of spirituality in the West.

Solzhenitsyn writes that it is precisely Marxist dogma that has created the economic absurdity of the Kolkhozes, the basic cause of the tragedy of the peasantry in the Thirties, and of the economic difficulties of the country today. This dogma has led to the bureaucratization of the national economy, and to the impasse that now makes it necessary to sell off the nation’s natural resources. It is the same dogma that causes our government to pay, at our people’s expense, Latin American revolutionaries, Arab nationalists, and Vietnam guerrillas. It is the same dogma that compels us to threaten the world with the thermonuclear weapon, and thereby to expose to extreme peril, and bring to ruin, not only the rest of the world but ourselves. It is this same dogma that, more than territorial disputes, provokes us to quarrel with China.

Advertisement

In the foregoing I have set forth Solzhenitsyn’s arguments rather freely, as I understand them. I regard many of these ideas as important and well taken, and this new, skillful defense of them gives me great pleasure. But at the same time I believe that in certain important respects Solzhenitsyn’s arguments are unsound, and in the most critical matters.

Let me begin with a question which is perhaps not so important in its concrete results but which involves an issue of principle. Sorrowing for his country, and with righteous indignation, Solzhenitsyn describes accurately the many ineptitudes and costly absurdities of our domestic life and foreign policy. But his view of their inner mechanism, as the direct result of ideological factors, seems to me somewhat schematic. To speak in particular, what characterizes the present state of society is ideological indifference and the pragmatic use of ideology as a convenient “façade,” even though this pragmatism and the flexibility in substituting appropriate slogans are combined with traditional intolerance toward dissent “from below.” Just as Stalin committed his crimes not directly for ideological motives but in a struggle for power while creating a society of the new “barracks” type (according to Marx’s formulation), so the leaders of the country now use the preservation of their power and the basic characteristic of the system as the chief criteria in making difficult decisions.

Likewise, I do not share Solzhenitsyn’s view of the role of Marxism as a supposedly “Western” and anti-religious doctrine which has distorted the healthy Russian pattern of development. The very division of ideas into Western and Russian is incomprehensible to me. In a scientific, rational approach to social and natural phenomena, ideas and concepts are divided into true ones and fallacious ones. And where is that healthy Russian pattern of development? Has there really been even one moment in the history of Russia, or in any country for that matter, when it was capable of developing without contradictions and cataclysms?

What Solzhenitsyn writes about ideological ritualism and the harmful waste of the time and efforts of millions of people on this nonsense, inculcating in them both hypocrisy and the habit of mouthing empty phrases, is incontestable. But under present-day conditions this nonsense replaces the old “oath of fidelity” and binds people in a mutual guarantee of the sin of hypocrisy. It is an example of the expedient idiocy engendered by the system.

Solzhenitsyn’s exposition of the problem of progress seems to me especially inaccurate. Progress is a world-wide process which is not at all identical—at any rate in the long view—with the quantitative growth of industrial production. The scientific and democratic regulation of the world economy and all social life, including the dynamics of population, is not, I am profoundly convinced, a utopia but a very real necessity. Progress must continuously and expediently change its concrete forms, meeting the demands of human society without failing to preserve nature and the land for our descendents. Retarding scientific investigations, international scientific contacts, technological research, new systems of agriculture, can only postpone the solution of these problems and create critical situations for the world.

The most dramatic of Solzhenitsyn’s theses has to do with the problem of China. He believes that because of the struggle for ideological supremacy and because of demographic pressure, our country faces an imminent threat of total war with China for the Asian territory of the USSR. He sees this war as the longest and bloodiest in the history of mankind—one in which there will be no victors but only general destruction and a reversion to savagery. He asks that this threat be deflected by a renunciation of ideological competition, by Russian patriotism, and by development of the north-eastern part of the country. At one time, in my “Memorandum,”3 I also entertained apprehensions of this kind.

But I now think that view overdramatizes the situation—which of course is not a simple one, and not unclouded. The majority of experts on China share the opinion that for a relatively long time China will not have the military capacity to wage a large-scale aggressive war against the USSR. It is difficult to imagine that the sort of adventurers exist who would today urge China to take such a suicidal step. For that matter, aggression on the part of the USSR would also be doomed to failure. One may even hazard the hypothesis that the exaggeration of the Chinese threat is one of the elements in the political game of the Soviet leadership. This overstatement of the Chinese menace scarcely helps the cause of the democratization and demilitarization of our country, which it needs so badly—and which the whole world needs.

Advertisement

The fact that the fate of the Chinese people, like that of many other peoples of our world, is tragic and should be the concern of all mankind, including the UN, is another matter. Concerning the problem of the conflict with China—which in my opinion is a geopolitical struggle for hegemony—Solzhenitsyn, as in other passages of his letter, overrates the role of ideology. Apparently the Chinese leaders are no less pragmatic than their Soviet counterparts.

I should now like to examine Solzhenitsyn’s positive program, which is aimed at avoiding war with China and preventing the destruction of the Russian environment, land, and nation. I shall summarize these suggestions in the form of the following points. (Needless to say, I again bear the responsibility for the formulation, and the sequence of the points.)

- Renunciation of the official support of Marxism as an obligatory state ideology (“separation of Marxism from the state”).

- Withdrawal of support from revolutionaries, nationalists, and partisans throughout the world; concentration of efforts on domestic problems.

- An end to the trusteeship of Eastern Europe; renunciation of forcible retention of the national republics within the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

-

Agrarian reform following the model of the Polish People’s Republic (my formulation).

-

Development of the northeastern part of the country on the basis of “non-progressive” but modern technology without huge factories and with the preservation of the environment, the quiet, the soil, etc. Obviously, Solzhenitsyn has in mind populating the northeast with communes of volunteer enthusiasts. Solzhenitsyn seems to consider these prospective settlers as patriots inspired by national and religious ideas. It is precisely to them that he proposes to bestow the liberated resources of the state and the results of scientific research, making possible for them high personal incomes from their labor. But the northeast will also be an outpost against China and a preserve (a “reservoir,” as he puts it) for the Russian nation. It will be a basic source of wealth for the whole country.

-

A halt to the sale of national resources, natural gas, timber, etc.; economic isolationism as a complement to military, political, and ideological isolationism.

-

Disarmament to the degree permitted by the Chinese threat.

-

Democratic freedoms, toleration, and the liberation of political prisoners.

-

Strengthening of the family and education; freedom of religious education.

-

Preservation of the Party, but with a revitalization of the role of the Soviets. Preservation of the basic authoritarian aspects of the system is permissible, with reinforcement of the laws and the legal order accompanied by freedom of conscience.

Solzhenitsyn’s program is the result of serious thinking—the expression of a system of opinions in which he sincerely believes. Nonetheless, I am compelled to state that I have serious objections to this program. Of course one must agree with the suggestions contained in points 2, 3, and 4. For that matter, in my exposition I involuntarily emphasized point 3, which strikes me as extremely important from both the moral and political viewpoints. (In Solzhenitsyn’s letter, this thesis was advanced only in a footnote.) Point 1, requiring renunciation of the official state support for Marxism, is incontrovertible. But I have already said that one tends to exaggerate the role of the ideological factor in the present-day life of Soviet society.

Points 7, 8, and 9 are likewise arguable, although this is not the first time they have figured in democratic documents. But their repetition by a prestigious author is not superfluous, and they are well presented in the letter.

In justifying the tenth point in his program, Solzhenitsyn writes that perhaps our country has not matured to the point of democratizing the system, and that when accompanied by respect for law and by Orthodoxy the authoritarian system was not all that bad, since under that system Russia preserved its national health until the twentieth century.

These opinions are alien to me. I consider the democratic path of development the only possible one for any country. The servile, slavish spirit which existed in Russia for centuries, combined with a scorn for people of other countries, other races, and other beliefs, was in my view the greatest of misfortunes. Only under democratic conditions can one develop a national character capable of intelligent existence in a world becoming increasingly complex. Of course there is a kind of vicious circle here which cannot be overcome in a short time. But I don’t see why this is not possible in our country. In Russia’s past there were several democratic achievements, beginning with the reforms of Alexander II. I do not recognize the arguments of those Westerners who consider the failure of socialism in Russia to be a result of its so-called lack of democratic traditions.

Points 5 and 6 are most important and central to Solzhenitsyn’s own program; and they require a more detailed analysis. First of all I object to the endeavor to protect our country against the allegedly pernicious influence of the West—against trade, against what is called “the exchange of people and ideas.” The only form of isolationism that makes sense is not to intrude upon other countries with our messianic socialist notions; to discontinue our covert and overt support of subversion on other continents; to discontinue our export of deadly weapons.

Is the intensive development of the northern areas possible today in view of the present sparse population, the harsh climate, and the lack of roads? Can it be done using the economic and technical resources of our country alone—a country whose reserves are already strained? I am convinced that this is impossible. Therefore, the rejection of the international cooperation of the US, West Germany, Japan, France, Italy, England, India, China, and other countries in this development, of imports of equipment, capital, and technical know-how, of the immigration of workers, would mean an unconscionable delay in the development of these areas—a “dog-in-the-manager” policy.

I am convinced, unlike Solzhenitsyn, that no important problem can be solved only on a national scale. In particular, disarmament, which is so essential to the elimination of the danger of war, is obviously possible only on the basis of agreement and trust among the great states. The same thing applies to a shift to an environmentally harmless technology, which will inevitably be more costly, and to the limitation of the birth rate and industrial growth. These issues are complicated by international competition and national egoism.

Only on a global scale is it possible to solve the scientific-technical problems of our time such as the creation of nuclear and thermonuclear energetics, a new agricultural technology, the production of synthetic substitutes for albumin, the problem of building cities, the construction of an industrial technology that will not defile the environment, the mastery of space, the fight against cancer and cardiovascular diseases, the development of cybernetic technology. These tasks require outlays of many billions of dollars, which are beyond the scope of any individual state.

Our country cannot live in economic and scientific-technical isolation without world trade, including trade in the nation’s natural resources, and detached from world progress. Rapprochement with the West must have the character of the first stage of a convergence and be accompanied by democratic reforms in the USSR, partly self-initiated and partly prompted by economic and political pressure from abroad. There is great importance in the democratic solution of the problem of freedom to leave the USSR, and to return to it, on the part of Russians, Germans, Jews, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Turks, Armenians, all citizens. Then it will become impossible to retain other antidemocratic institutions in the country; it will be necessary to bring living standards into line with those in the West, and there will be free exchange of people and ideas.

A more complex problem is that of breaking up industry into smaller units, and of organizing it communally. I think Solzhenitsyn and his kindred spirits exaggerate the role of industrial gigantism in the development of the difficulties of the modern world. An optimal structure of industry depends upon so many concrete technical, social, demographic, and even climatic factors that to impose limitations would be unwise. The commune does not seem to me a panacea for all ills although I do not deny its attractiveness under certain conditions. Solzhenitsyn’s dream of the possibility of getting along with the simplest kind of equipment, almost manual labor, appears impractical and foredoomed to failure under the difficult conditions of the northeast. His program is more myth-making than a real project. But the creation of myth is not always a harmless thing, especially in the twentieth century: we yearn for them. The myth of a “reservoir” for the Russian nation may turn into a tragedy.

Let me summarize some of my objections to Solzhenitsyn’s letter. In my opinion, he overstates the ideological factor in contemporary Soviet society. Hence his belief that the replacement of Marxism by a healthy ideology—and he apparently sees Orthodoxy in this role—will save the Russian people. This belief underlies his whole conception. But I am convinced that the nationalist and isolationist trend of Solzhenitsyn’s thinking, and his special brand of religious-patriarchal romanticism, are leading him toward substantial mistakes, and make his proposals utopian and potentially dangerous.

In his letter Solzhenitsyn appeals to the leaders of the nation not merely rhetorically but actually, counting on at least some understanding on their part. It is difficult to disagree with such a desire. But is there anything in his proposals which, at one and the same time, is new for the nation’s leaders and acceptable to them? After all, appeals to Great Russian nationalism and enthusiasm for the development of virgin lands have already been undertaken. The appeal to patriotism is straight out of the arsenal of semiofficial propaganda. It automatically invites comparison with the notorious military-patriotic indoctrination and the campaign against “toadying to foreigners” of the recent past. During the war and until his death, Stalin broadly tolerated “tamed” Orthodoxy. These parallels with Solzhenitsyn’s proposals are not only surprising—they should put us on our guard.

It may be said that Solzhenitsyn’s nationalism is not aggressive; that it is of a mild, defensive character and aims to save and restore our long-suffering nation. But we know from history that the “ideologues” were always milder than the practical politicians who came after them. Among much of the Russian people and many of the nation’s leaders there exist sentiments of Great Russian nationalism combined with a fear of becoming dependent upon the West, and a fear of democratic reforms. Falling on such fertile soil, Solzhenitsyn’s mistakes may become dangerous.

I thought it necessary to write this article because of my disagreement with many of Solzhenitsyn’s proposals. But on the other hand I should re-emphasize that the publication of Solzhenitsyn’s letter is an important social phenomenon—one more instance of free debate on basic problems. In spite of the fact that some aspects of his world view strike me as fallacious, Solzhenitsyn is a giant in the struggle for human dignity in the tragic modern world.

—April 3, 1974

(translated by Guy Daniels)

THE PERSECUTION OF A SCHOLAR

In July, 1973, a young Soviet literary critic, Gabriel G. Superfin, was arrested in Moscow. He was charged with such crimes as association with the samizdat journal Chronicle of Current Events and having made notes on a copy of a recent Western study of Soviet dissidents, Peter Reddaway’s Uncensored Russia. Last December the Committee for the Defense of G. Superfin, a group which includes distinguished humanists such as Octavio Paz, Meyer Schapiro, and Robert Penn Warren, expressed grave concern over Superfin’s plight and urged the Soviet authorities to protect his basic rights.

It now appears that our apprehensions were far from groundless. After a long investigation in the course of which he was subjected to illegitimate pressures, Superfin was tried in the city of Orel and sentenced to five years of forced labor and two years’ exile. The sentence is being appealed. The Superfin Defense Committee is sending a cable to N. Podgorny protesting this miscarriage of justice and is alerting our colleagues in the West to the persecution of a gifted and dedicated scholar.

—Victor Erlich

Yale University

New Haven Connecticut

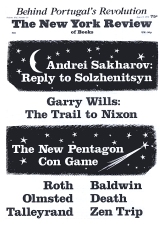

This Issue

June 13, 1974