In response to:

The DeFunis Case: The Right to Go to Law School from the February 5, 1976 issue

To the Editors:

Ronald Dworkin evidently supposes readers of his essay on the DeFunis case [NYR, February 5] share with him a special vocabulary. I found that without knowing how Professor Dworkin would answer several important questions, his argument is not quite comprehensible.

What, for instance, is meant by “treatment as an equal”? The example of the sick child is not of much help. Giving medicine to the one who needs it most seems merely rational, and not to have anything to do with equality. And I am afraid I can’t see any content at all in a statement about “interests be[ing] treated as fully and sympathetically as the interests of any others.”

What is an “ideal argument”? If I understood that I could no doubt understand why ideal arguments can only support giving preference to blacks, and not giving preference to whites, but at the moment that puzzles me.

Professor Dworkin appears to like ideal arguments as such, although it seems to me that since there are bad ideas as well as good ones, some ideal arguments must be bad too. I suppose the answer is that Professor Dworkin uses “ideal argument” to mean an argument from some particular ideal, but I’m still puzzled. It sounds to me as though any ideal argument is an argument based on “external preferences”—which is a kind of argument Professor Dworkin doesn’t like at all.

But, as it happens, that is another point not made clear to me. Professor Dworkin apparently means to show external preferences intrinsically wrong (well, he only says that we should leave them out of account, but it seems to follow that they’re the sort of thing decent people—in Professor Dworkin’s vocabulary, “liberals”—ought to avoid, if possible). His argument, though, consists of showing what comes of arguments based on particular external preferences. On the other hand, arguments for a welfare program, or any form of charity, must depend on external preferences. How does Professor Dworkin deal with this?

My own feeling is that it’s just such difficulties as the ones I’ve mentioned which make it important to have some less subtle principles to cling to: such as, that all discriminations based on race are wrong. Indeed, as a lawyer I’m nearly sure that’s so. No doubt philosophers can safely tread Professor Dworkin’s path, whatever its unseen windings, and come out right in the end. I would rather courts did not try.

I suspect there is also something to be said philosophically for condemning racial (sexual, religious, etc.) discrimination per se, but that’s another subject.

Michael Winger

New York City

To the Editors:

In “The DeFunis Case: The Right to Go to Law School” Professor Dworkin makes an admirable try at formulating a test against which to measure the acceptability of a policy of unequal treatment (in this case, reverse racial discrimination by a law school admissions committee). In the end he finds this policy not to be a denial of equal protection of the law. I agree with his result, but find some room in his reasoning to cavil.

I think it is not unfair to summarize Professor Dworkin’s argument as follows:

A policy of unequal treatment is not a denial of equal protection if it can satisfy two conditions: 1) It must be a “plausible policy,” i.e., it must seem to serve some legitimate objective (utilitarian or ideal). 2) It must respect the right of all members of the community to be treated as equals. i.e., equal consideration must be given to the interests of each.

The second condition makes good sense. It is a definition of equality which permits us to escape the dogmatic interpretations of “equality before the law” (as the concept is rendered in the Bill of Rights here in Canada). It opens the door to a justification of beneficial unequal treatment. But somewhat more is required before we can enter.

This additional requirement is what Professor Dworkin seeks to provide by the “plausible policy” test. It is here that I encounter difficulty. In DeFunis the admissions committee could point to various desirable social objectives which a preferential policy may or may not serve. According to Professor Dworkin, we ought to be satisfied if it is not implausible that they do so serve.

The question that occurs to me is this: How far along the road of proof do we have to travel before arriving at an acceptable demonstration that a policy of unequal treatment does in fact serve its stated objective? I suggest that we ought to be looking for a sterner standard of proof than an appearance of reasonableness or an appearance of probability, which is the way my dictionary defines “plausible.”

Let me illustrate the kind of difficulty that a plausibility standard gets us into. A controversey is now sweeping the Canadian political scene. For years Canadian governments have struggled with the problem of what to do with convicted murderers sentenced to hang. They have tried to cope by exercising the executive prerogative of commuting death sentences to life imprisonment. Over the years they have commuted some and executed others—unequal treatment of the most invidious kind.

Advertisement

This practice is vocally opposed by two groups from two different directions. One group says hang ’em all. The other says we should abolish capital punishment altogether.

Is a commutation policy justifiable according to the Dworkin test? Does it protect the right of all to be treated as equals? The answer must be yes, for each case receives the most painstaking and thorough consideration imaginable. This happens on top of the exhaustive operation of due process of law in the courts.

Next we need to show that the policy is plausibly linked to some legitimate objective, utilitarian or ideal. From a utilitarian point of view, one might say that commutation raises the general welfare of society by reducing the murder rate. Those sentences not commuted serve as deterrent examples. Or, on the ideal side, one could say that in an ideal society justice ought to be tempered with mercy. A policy of commutation seems to serve this ideal. Commutation is, therefore, a plausible policy, and no denial of equality before the law.

But let us look at the arguments of the abolitionists and the retentionists, both in opposition to commutation. On the utilitarian front, they say commutation does not promote the general welfare, but its opposite. Because it is seen to be arbitrary it undermines respect for the law in general and thus encourages crime.

At the ideal level, the opposition says there are ideals just as important as tempering justice with mercy, if not more so. Here we can choose between the sanctity of human life as an ideal, or a punishment that fits the crime. Both groups can say that the fairness and thoroughness of the judicial process will ensure that all are treated as equals. All of this bears an appearance of reasonableness.

So we see the difficulty of Professor Dworkin’s test: Where a plausible policy of unequal treatment is met by equally plausible arguments against it, we end up by opting in favor of unequal treatment. This in effect means that we place an (almost unattainable) onus on the opponents of unequal treatment to prove that it is wrong.

Isn’t this a reversal of the way it ought to be? Surely the onus ought to rest on the proponents of unequal treatment to justify it, and on a more stringent basis than a mere showing of plausibility?

Look at the DeFunis case again. Professor Dworkin lists the utilitarian objectives apparently served by a preferential admissions policy: More black lawyers will provide better legal services to blacks, thus easing social tensions. Legal education will be improved by having black students take part in classroom discussion. It will encourage blacks who do meet the intellectual criteria to apply to law school, and thus raise the quality of the bar.

It is not implausible to argue contrarily that it will make no significant difference to the quality of legal services available to blacks, or to the quality of legal education, or to the quality of the bar, if the students being accepted do not meet a superior intellectual standard.

Then there is the ideal justification—that the policy will make the community more equal overall by decreasing the disparity in wealth and power between racial groups. But it appears equally reasonable to say that a preferential admissions policy will produce an educated, but intellectually average, elite which will prey on its less privileged brothers, thereby doing little to decrease disparity between racial groups, but merely readjusting inequality within the racial group itself.

Any further comparison of the reasonableness of these competing assertions takes us beyond the level of plausibility and requires a different formulation of the standard of proof. That is what has to be done. May I suggest the old tried-and-true? Proof on a balance of probabilities, with the onus on those who seek to justify a policy of unequal treatment? Such a standard at least has the advantage of articulating the criteria by which we should choose from among equally plausible assertions.

Under such a standard, I suspect the admissions committee would have nothing to fear, although commutationists might find the going a little rough.

I must leave to another occasion the other interesting questions raised by Professor Dworkin’s article. (What is a legitimate objective? Are not ideal objectives ultimately reducible to some utilitarian formula? How do we choose between competing ideals?)

Finally, Professor Dworkin should be congratulated for his exposé of “preference utilitarianism.”

Advertisement

Glen W. Bell

Counsel

Indian Brotherhood of the

Northwest Territories

Yellowknife, NWT

Ronald Dworkin replies:

Mr. Bell rightly points out (as I did in my article) that it is controversial whether a preferential admissions policy will serve the utilitarian and ideal goals I mentioned. I said that the question of whether the policy will indeed serve these goals should be at the center of the political debate; my argument was directed against the claim, urged in DeFunis, that the policy is wrong even if it does. But Mr. Bell wishes to add a proposition to that debate that I believe will not be helpful.

He says that when it is plausible but not certain that a particular policy will achieve the goals it promises, then the “onus” should be “on those who seek to justify a policy of unequal treatment.” But though this precept might have some force in the case of capital punishment he describes, it is unclear how it bears on the problem of university admissions. Any admissions policy is, in the nature of the case, a policy of “unequal treatment.” Who, therefore, has the onus of proof in a dispute between those who favor admissions by test scores alone and those who favor some mix of minority preference? If the point of this allocation of the burden of proof is, as Mr. Bell suggests, to create a presumption in favor of equality, then the benefit of the doubt should be given to the policy of minority preference, because that policy, unlike its competitor, at least aims at improving equality in the community overall.

In fact, however, the idea of a burden of proof is of little help here. A law school does wrong to adopt a preferential policy unless the school itself is satisfied, on what Mr. Bell calls the “balance of probabilities,” that the policy will in fact improve rather than retard racial equality; but if the school does in good faith believe that it will, then, in the present state of knowledge, it seems wrong to ask for some higher standard of proof before that school is allowed, for its own part, to follow its own judgment.

Mr. Winger raises a number of points. He says he finds no content at all in an abstract political principle which demands that the interests of each member of society be treated as fully and sympathetically as the interests of any other. It may be few people would disagree with that principle (except for racists and those who believe in caste or the privileges of birth or talent). It does not follow, however, that the principle is empty, but only that it is incumbent on political philosophy to describe, more helpfully, the content it has. Utilitarianism, in its various forms, attempts to do so. I argued that traditional forms of utilitarianism fail to explicate the content of the abstract principle, and that only a theory that recognizes the distinctions I suggested could succeed.

Mr. Winger is simply wrong, moreover, about the case of the sick children. If I care much more for one child than another, it would be perfectly rational to give the medicine to the child I prefer even if he needs it rather less, but it would not be treating the two children as equals.

He is also confused (though I’m sure the fault is mine) about the connection between ideal arguments and external preferences. An official uses an ideal argument when he justifies a decision by direct appeal to some proposition, of political morality, like the proposition, which I think is right, that equality is a civic virtue, or the proposition, which I think is wrong, that a caste system is morally superior. He uses a utilitarian argument based on external preferences when he justifies a decision by appeal to the fact that a majority accepts some proposition of political morality, like a preference for equality or for a caste system, which is a very different matter.

A critic criticizes an ideal argument by challenging the intrinsic soundness of the political morality on which it is based; he might challenge, for example, any decision based on the ideal argument that a caste system is desirable. He criticizes a utilitarian argument based on external preferences, however, simply by pointing out that the argument is so based, whether he himself holds the external preferences in question or not.

It is, of course, no part of my argument that all external preferences are bad in themselves, or that people should not hold external preferences. On the contrary, no one could be a liberal unless he or she held certain external preferences, namely liberal ones. My argument is only that a utilitarian argument should not rely simply on the fact of popular external preferences, good or bad.

Consider Mr. Winger’s example of the welfare scheme. A welfare program may be justified on proper utilitarian grounds: it may promote collective preferences counting only personal preferences. It may also, and independently, be justified by an ideal argument of fairness. In either case, it is no less justified in a society where the majority’s external preferences oppose a welfare program than in a society in which their external preferences commend it, though as a political matter the program would have much more chance of acceptance in the latter society. Programs of social justice must stand or fall on their own merits; their popularity or unpopularity, though crucial to their chance of acceptance, cannot add to or detract from those merits.

Neither of these letters urges a point made by many other letters I have received. Many letters argued that intelligence is the only proper ground for selection to a law school, just as skill at playing basketball is the only proper ground for selection to a basketball team. I tried to anticipate that argument, but it might be useful to summarize what I said. The provision of a legal education to a highly selected group of students, with the use of public funds, does not serve any single or “essential” goal in the way that the selection of a group of basketball players for a commercial team is generally understood to do. Legal education serves a mix of social goals. It is not only sensible that law schools consider what the right mix should be, but irresponsible if they do not.

I share Mr. Winger’s distrust of courts—I distrust philosophers too. But the remedy does not lie in simple rules, because these will often be abandoned, as the DeFunis litigation suggests, when they are felt to work injustice; they will not be followed just because they are simple. It is better to liberate reason, with all the risks, than to stifle it in slogans.

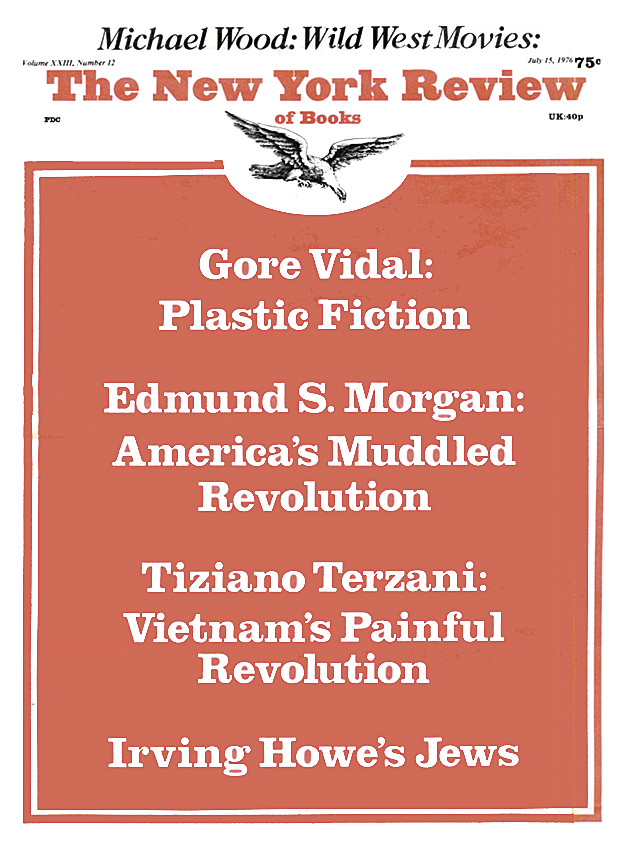

This Issue

July 15, 1976