This first anthology of Evelyn Waugh’s reviews, articles, prefaces should have been more comprehensive, if only to display more of his variety. The editor’s comments betray reservations concerning present-day interest in some of the unselected material. He need have none. Thanks to such developments as Idi Amin and the Arab occupation of Britain, Waugh’s views seem much less rabidly reactionary now, and in fact are being embraced by the liberals whom he once attacked. Moreover, his journalism is never dull—unlike his diaries, which he did not choose to publish—and the writing is a continual delight. For marksmanship, and elegance as well as economy of language, no one currently reviewing books even approaches the standard of the best in this too slender volume.

The earliest pieces in A Little Order are the most surprising, especially some remarkably accomplished paragraphs on cubism, written at age fourteen. Reaching twenty-one (1924), Waugh recommends a new war, suggesting, among possible provocations, the invasion of America “in the cause of alcohol.” A few years later, calling attention to the existence of a “younger generation,” he observes, “I do not know why that should be so, because, of course, people are born and grow up daily, and not in decades.” By the late 1920s he is increasingly epigrammatic: “The arts offer the only career in which commercial failure is not necessarily discreditable.” And by this date, too, he is fabricating dialogue that might have been used in Vile Bodies, as, for example, in this exchange at the time of a fad in romans-à-clef: ” ‘Have you read so-and-so’s new novel?’ ‘No. Who’s in it?’ ”

The choice of articles and reviews by the somewhat older Waugh, the Roman Catholic convert and the political Tory, must be faulted. The book contains no specimen of his war reporting, of which “Commando Raid on Bardia” (Life, 1943) must be among the finest of its kind, or any of the travel pieces, neither the Spitzbergen expedition nor the trip to Goa, nor even “Honeymoon Travel” (an article that refutes the statement in Christopher Sykes’s biography that Waugh does not allude in any of his work to the 1946 visit to Spain). Missing, too, are such specialities as the reviews of Who’s Who

Why is Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes listed under F and Adm. the Hon. Sir R.A.R. Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax under P?

and of handbooks on etiquette (“The Amenities in America”), though the writer at his most querulous is more than amply represented in a reply to J.B. Priestley’s critique of The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, and in a pathologically vindictive description of an encounter with two would-be interviewers. The latter article might at least have been offset by the inclusion of Waugh’s impersonal and entertaining skit, “Today’s Interviewing Techniques” (Vogue, 1948).

The novelist is admittedly less brilliant when bestowing an accolade, of which the dictionary’s second meaning is “a light blow with the flat of the sword,” than when using this weapon as a skewer. But the book’s most outrageous piece in this sense, the review of Stephen Spender’s World Within World, animadverts upon the editor for having chosen to include an assault on only one living writer; the editor would have been kinder to have offered, as well, such massacres as those of Truman Capote and Cecil Beaton (Spectator, March 20, 1954, and July 21, 1961), which would also have put Waugh in a different perspective. Furthermore, these two additions would have been an asset to the book since Waugh is at his best when inveighing against abuses of syntax and fumbling prose. Still another solution would be to have placed the two pieces on Cyril Connolly immediately after the one on Spender, beginning with, as Waugh calls it, “The Horizon Blue-Print of Chaos.” One of Connolly’s precepts for social reform was that “light and heat [be] supplied free, like air and water.” But, as Waugh notes, “air is not ‘supplied,’ and water is rarely ‘free.’ ” Incidentally, his analysis of Connolly’s failure to achieve “his avowed objective of writing a durable book” seems extraordinary perceptive today:

What makes a writer, as distinguished from a…cultured man who can write…[is] a breadth of vision which enables him to conceive and complete a structure. Critics, in so far as they are critics only, lack this, Mr. Connolly very evidently….

On the evidence of A Little Order, Waugh was at his peak as an essayist in 1944, as exemplified in his demolition of Harold Laski’s Stalin-worshiping Faith, Reason, and Civilization, an article that will be read with considerably more approval today than it was at the time. Waugh’s indignation is not yet ill-tempered, his language is without any fat or the alliterative indulgences that sometimes mar the later reviews (“Scobie arrogates to himself the prerogatives of Providence”), and the writing is dated only by its excellence. This last cannot be said of Laski:

Advertisement

Had we not the Professor’s assurance that [his book] is “essentially an essay, nothing more,” we might take it for something much less…. Diffuse, repetitive, and contradictory…the argument so far as I can claim to have followed it through the hairpin bends and blind alleys in which it abounds… [is that] the “values” of the past are dead; they are not to be found in art because Mr. T.S. Eliot is not understood by manual labourers and James Joyce is understood by nobody. “Values” can only be found now in Soviet Russia; the battle of Stalingrad proves it….

Waugh’s historical examples quickly dispose of the argument that “heroic military defense” is “conclusive evidence that the defenders have superior ‘values’ to the attackers.” He then turns to Laski’s analogy between Christianity and Marxism:

the latest imposture [Marxism] is more grossly impudent than its predecessor, Christianity, for the latter said, “Ye will be happy hereafter,” and cannot be proven wrong (until Professor Laski’s scholars get to work), while the former says “My dear comrades, you may not realize it, but you are happy at this moment.”

Many readers will enjoy A Little Order above all for the particulars of its criticisms of fiction—rather than its literary judgments, which may be attributable either to teasing (“The best American writer, of course, is Erle Stanley Gardner”) or to friendship (“[Ronald Knox’s] Enthusiasm [is] the greatest work of literary art of this century”). Defending Angus Wilson’s Hemlock and After from critics who had condemned one of the book’s characters (Mrs. Curry, the procuress) as unbelievable, Waugh says:

I was able, at a pinch, to accept her…. It would not be surprising to learn that she had in fact been drawn quite accurately from life. [This is] often the case with the least plausible characters in fiction and when it happens it marks an artistic failure on the part of the writer.

Yet Waugh’s distinction that the character is credible but not her methods seems to the present writer to be splitting hairs. Waugh goes on to answer the critics’ further objection that the odiousness of the characters places them beyond interest:

There is a superfluity of…wicked people…but there is an almost equal number of people who under other eyes than Mr. Wilson’s might be quite likeable. Mr. Wilson is unique in his detestation of all of his creations….

The reason for this, Waugh speculates, might be a preoccupation with class that will detract from Wilson’s artistry. The observation is shrewd, even prophetic, for Wilson seems to have become more sociologist than novelist.

And Waugh’s own class obsessions? Certainly they do not harm A Handful of Dust or “Mr. Loveday’s Little Outing,” the best of his imaginative world. This, we once thought, was too thickly populated by charlatans and cads, too sparsely by decent victim-types, while the inexorable rule of chance seemed exaggerated. Today, however, whether we regard Fate as a script written long ago and waiting to be enacted, or simply as hindsight, the end no longer seems, to use Waugh’s favorite word, preposterous.

Touched off by a single typographical error in one book that he reviews, Waugh fusses about “imperfect proof reading.” But A Little Order is strewn with such slips: “I know what I lilke,” “a Sévres vase,” “[the comedian] Charles Chaplain,” “the world seemed full of exicting new books,” “We do not except them to grow any older,” etc., etc. More distracting still, the editor assigns each piece to a category: “Myself,” “Aesthete,” “Man of Letters,” “Conservative,” “Catholic.” But even if Waugh’s opinions warranted this kind of separation, these writings do not fit the compartments. Thus about half of his notice of Peter Quennell’s Hogarth is omitted for the peculiar reason that “it is unrelated to narrative painting”—as if anyone would read the book because of an interest in that subject rather than in Waugh on no matter what.

Thus, too, Waugh’s discussion of The Heart of the Matter is found not in the section under “Aesthete,” on novels, but under “Catholic,” and this though he disclaims competence in the theological questions raised by the book, and though his most valuable observations concern Greene’s style and cinematographic storytelling technique; even the remarks on the Péguy epigraph to the novel are centered less on doctrinal validity than on the use of two words. One suspects that A Little Order does not include Waugh’s review of The Quiet American simply because it could not be classified under “Catholic.”

The editor is obtrusive in other ways, too, and in fact is not on hand only when actually needed.* He introduces his five categories unnecessarily and not always literately, referring to the novelist as “far too daemonic”—can one be acceptably daemonic?—and “apt [sic]…to rewrite,” a habit evidently not shared by the editor, who admires

Advertisement

…the discipline and strength of purpose which enables [Waugh] to defy the temper of the times and his natural inclinations….

But how can anyone be certain that Waugh was not following, rather than defying, his natural inclinations?

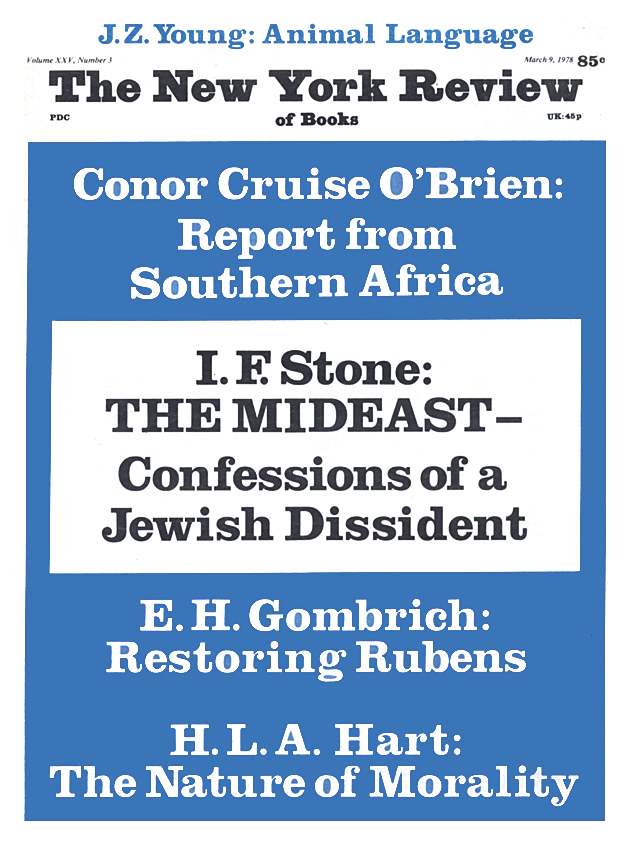

This Issue

March 9, 1978

-

*

In a memorial for Alfred Duggan, Waugh mentions that the novel Count Bohemond will appear posthumously, but a footnote should have informed the reader that this book was published in 1964, and with a preface by Waugh, a better-written tribute than the radio talk included in A Little Order. ↩