In 1966 Barbara Pym records in her diary that she is reading an account of someone that “made me laugh—people lying ill in the Dorchester and dying in Claridges.” “My own story,” she goes on, “judiciously edited from these notebooks would be subtler and more amusing.” This reinforces the feeling given by the diaries that, frank and entertaining as they are, they conceal as well as reveal. For what is Barbara Pym’s own story? Why did she choose the words “subtle” and “amusing” for it, and do they quite fit the life history as told in diaries and letters here? The “story” ostensibly is the quiet progress of an unmarried lady novelist who produced ten books, very gently satiric ones, very English, much concerned with the provision of cups of tea in adversity and the workaday aspects of the Church of England. But seeing the life in close-up we can find that there is much more to be known about this writer’s life.

The beginning of the story, anyway, is as bright as daylight: the future creator of churchy spinsters and mopish curates was a radiantly pretty girl with a passion for clothes, “the flicks,” punting, ginger beer and ice cream, and, above all, young men. Her Oxford diaries from the early 1930s might be those of any other ebullient and romantic young sprig. On one page alone, we find her devoted to black velvet dresses, kangaroos, Moll Flanders, Leslie Howard, “Stormy Weather,” and peach-colored lace underwear—an admirable selection. “Disgraceful I know but I can’t help choosing my underwear with a view to it being seen!” Barbara Pym was ravenously inquisitive about people herself, so we may reasonably be prompted by the peach underwear to wonder: how far did her string of love affairs (sentimental, unhappy) go? The diaries don’t reveal it, apart from one entry in 1932, when she was nineteen: “I went to tea with Rupert (and ate a pretty colossal one)—and he with all his charm, eloquence and masculine wiles, persuaded…. [Here several pages have been torn out.]”

Soon the diaries’ account of Oxford frolics gives way to a very long-term unrequited love, the first and foremost of a series to last thirty-five years. She stalks the streets where she might meet him, he actually speaks to her (“felt desperately thrilled about him so that I trembled and shivered and went sick”), he is offhand with her, he allows her to type his manuscript for him. Here the world of Sandra (Barbara Pym’s assumed name at Oxford) takes a first step toward that of the author of novels of pianissimo love and loss. In 1937 Henry Harvey, the loved one, marries someone else and in the diary she inscribes So endete [sic] eine grosse Liebe. She writes, however, a brilliant series of letters to him and his wife over the next few years, showy and arch and just slightly edged with malice.

Meanwhile, a couple of years after Oxford, she had written Some Tame Gazelle, in which Henry Harvey figures as the mellifluous but ever so slightly ridiculous Archdeacon Hoccleve. It is typical of a Pym novel that all the teasing is benign, and if there is any hostility toward men for their insensitivity, it vanishes on a breeze of the gentlest ridicule. Women do adore these creatures, is her attitude; isn’t it a splendid joke? The book was turned down by publishers, and in 1939 she completed another (still unpublished). Writing had by now become her job: “I honestly don’t believe I can be happy unless I am writing. It seems to be the only thing I really want to do.” But war was to intervene.

In 1941 she moved to Bristol to do war work in the censorship, and shared a large house called The Coppice with a dozen others. Here unrequited love reared its head again. One of the women in the house—a close friend—was divorcing her husband, and Barbara Pym fell in love with him. He took the relationship more lightly than she did, and after a while broke it off. It is clear that she went on being unhappy for a long time. But the code of the “excellent women” prevailed—“one always has to pick oneself up again and go on being drearily splendid.” By this stage in the diary we recognize a muting of feelings, a position somewhere between the larky girl of the early pages and the stoical, amused Miss Pym of middle age.

Oh mumbling chumbling moths, talking worms and my own intolerable bird give me one tiny ray of hope for the future and I will keep on wanting to be alive. Yes, you will be alive, it will not be the same, nothing will be quite as good, there will be no intense joy but small compensations, spinsterish delights and as the years go on and they are no longer painful, memories.

To escape from the situation she joined the WRNS (the women’s navy) and spent some time, notably chic in officer’s uniform, in the Mediterranean (even this un-Pymlike experience is brought into the books via the naval officer Rocky in Excellent Women). Minor characters in the sentimental procession of unrequited loves came and went. In 1946 she was demobilized and took a job, which she was to keep until retirement, as assistant editor of an anthropological journal, and for a few years there are virtually no diary entries.

Advertisement

Probably this was because she was really writing at last. Some Tame Gazelle, written before the war, was offered again and this time accepted. It was published in 1950. “Delightfully amusing,” wrote one critic, “but no more to be described than a delicious taste or smell.” True; the Pym flavor, whether you like it or find it insipid, is almost impossible to pin down; it makes critical adjectives look gross and clumsy, like big hands in a doll’s house. Over the next thirteen years six novels came out. It is striking that, with all the experiences over the years that separated the writing of the first novel when she was twenty-three from the next when in her thirties, her style and type of subject did not change a fraction. From the start she knew the kind of books she intended to write.

In 1963 came the blow: Cape turned down her latest novel (it wouldn’t sell, it wasn’t what the Sixties wanted), and she entered her fourteen-year period of publishing ostracism. “Drearily splendid” though she was about it, the diaries contain muted protests against her fate. “In the restaurant all those clergymen helping themselves from the cold table, it seems endlessly. But you mustn’t notice things like that if you’re going to be a novelist in 1968–9 and the 70s. The posters on Oxford Circus station advertising Confidential Pregnancy Tests would be more suitable.” “What is wrong with being obsessed with trivia? Some have criticized The Sweet Dove for this. What are the minds of my critics filled with? What nobler and more worthwhile things?” “Mr C in the Library—he is having his lunch, eating a sandwich with a knife and fork, a glass of milk near at hand. Oh why can’t I write about things like that any more—why is this kind of thing no longer acceptable?” She continued to write and to send manuscripts around the publishers, but without success. At about this time there was another of her sentimental episodes, the basis of The Sweet Dove Died: love for a younger man, fruitless and painful.

In 1974, after an illness, she retired from work to share a country cottage with her sister (oak beams, cats, and a church, unfortunately, that was “not very high”)—thus fulfilling the picture she drew at twenty-three in Some Tame Gazelle of the two of them as cozy village spinsters. Marmalade-making and patchwork are mentioned and there were, no doubt, vicarage jumble sales. And now comes the moment of high drama—and irony—in Barbara Pym’s life. It is 1977, the retired Miss Pym is sixty-three; the Times Literary Supplement as a New Year’s gimmick runs a feature about the most underrated and most overrated living writers. Independently, two literary personages choose Pym as most underrated. The story makes the front page of The Times, and the ball begins to roll. Photographers and interviewers come running; more important, a new publisher snaps up her last two unpublished novels, which come out to friendly reviews. One, in fact, is nominated for the Booker Prize, though it does not win. The irony, though, is that Barbara Pym is soon to have a terminal return of cancer.

She died four years ago, at sixty-six, in a hospice in Oxford, and her books have acquired something of a minor cult readership. Curiously enough, she seemed to foresee the shape of her life. Twice in her unpublished years she toyed with the idea of being rediscovered: “In about ten years’ time, perhaps somebody will be kind enough to discover me, living destitute in cat-ridden squalor.” And when she was young she liked to play the game of genteel churchy ladies and was fond of calling herself “spinster” (a word that scarcely has meaning now but certainly did in Barbara Pym’s day).

Why the sequence of unattainable, yearned-over men in her life? Hilary Pym has described how formidably attractive and well dressed her elder sister was, and photographs confirm it. But the title of one of the novels, No Fond Return of Love, sums up a predominating theme in the life and in the books. Seldom does a Pym woman “get the guy” (with what fastidious amusement she would have regarded such a phrase!). When a friend writes that he is going to spend a year at an Oxford college it sparks off a plot:

Advertisement

Middle-aged unmarried female don waits eagerly for the autumn when a friend of her Oxford days (the well-known poet, librarian and whatever else you like) is coming to spend a year at All Souls (doing some kind of research, perhaps). At first it is all delightful and they go for beautiful autumnal walks on Shotover (?can one still do this) but unknown to her he has been visiting a jazz club in the most squalid part of the town (where is that now?) and has fallen in love with a nineteen year old girl…the ending could be violent if necessary—or he could just go off with the girl, leaving the female don reading Hardy’s poems.

Of course, its being a Pym plot, the woman has to be hopeful and then betrayed. It seems that in life and in fiction Barbara Pym could not envisage the plot of woman gratified or triumphant. Even “splendid,” which might mean something quite different, to her means being stoical in dreary circumstances. Perhaps she needed to write so much that love affairs were deliberately chosen for their fruitlessness; a friend, she reports, “thinks perhaps this is the kind of love I’ve always wanted because absolutely nothing can be done about it.” Perhaps what she liked most were moments of sentiment; she remarks on “what a great pleasure and delight there is in being really sentimental…. People who are not sentimental, who never keep relics, brood on anniversaries, kiss photographs good-night and good morning, must miss a good deal.”

The diaries show little sign of introspection and psychological complication. When they are not concerned with the various men preoccupying her they act as a kind of ragbag for the odd and Pym-like observation. Lunch hours, for instance, she makes rather a specialty of: overheard conversations in the Kardomah café in Kingsway, rambles around City churchyards where shabby dignified women drink coffee from plastic cups. She keeps modestly up with the times: John Lennon, so “like a very plain middle-aged Victorian female novelist”; and “Did you see on the back of the Sunday Times today about the girl who is starting the Orlando Press, erotic books written by women for women? What can they possibly be like? (I shall look out for them with interest.)” Christianity in its mundane details is a recurring note: “Buying Christmas cards in Mowbrays [church shop]—one feels one can’t push”; “Why should there be a notice to say ‘Marmalade for Sale’ in the window of the Hibernian Church Missionary Society?”; a sentence for a novel—“If only, Letty thought, Christianity could have had a British, even an English origin! Palestine was so remote, violence on one’s TV screen.”

Interspersed among the later diaries are her letters to the poet Philip Larkin, first an epistolary admirer and then, after a nervous meeting, a friend. Larkin, something of a male, poetic Pym (or alternatively she was something of a female, prose Larkin) was an ideal correspondent and the letters seem to hover on the verge of laughter. Tongue-in-cheek, surely, was the discussion of Mr. Larkin’s Panama hat (“32/6 seems expensive but not when you think of it as an investment“), Mr. Larkin’s doctoral robes (“Is there a floppy hat to go with them? A pity you can’t be photographed in them for your 1969 Christmas card—or perhaps you have been?”), and Mr. Larkin’s holiday (“Many thanks for your letter, and card from Northern Ireland. It seemed a very original place for a holiday…”).

Few diaries give us the whole person and the whole life; most diarists make it a receptacle for a particular kind of diary-fodder, and this is true here. We have to glimpse the life sometimes across gaps and between lines. For one thing, in spite of the numberless references to things ecclesiastical, we do not know anything about Barbara Pym’s faith—whether it was fiery or terre-à-terre, whether it had remained solid since childhood or had fluctuated. Clearly it was central to her life. Curiously, the churchy scene—curates to tea, jumble sales, squabbles over the altar decorations—which to the original generation of her readers was so pleasantly familiar, may be as exotically remote as Jane Austen’s settings to present readers.

So can her book lead us to understand how it was that she saw her story as “subtle” and “amusing”? It might have had the makings of being tragic, but avoided that. Perhaps it was amusing because, at the least, she never ceased to be an entertainer; and subtle, because she was a subtle person. “Comic and sad and indefinite” sums it up best, as it does all our lives:

“I’m so glad you write happy endings,” said Mabel. “After all, life isn’t really so unpleasant as some writers make out, is it?” she added hopefully.

“No, perhaps not. It’s comic and sad and indefinite—dull, sometimes, but seldom really tragic or deliriously happy, except when one’s very young.”

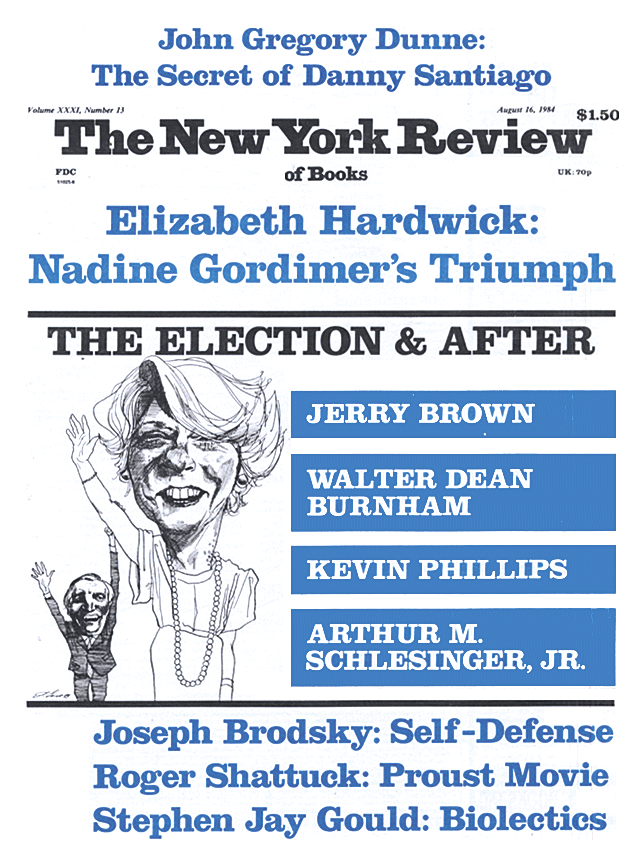

This Issue

August 16, 1984