History has taken an odd turn in the last few years. The professionals cleared it of kings and queens so that they could study the play of structures and conjunctures. But the most recent run of publications suggests a new range of subjects, one stranger that the other. We have had books on the lesbian nun, the anorexic saint, the wild boy, and the pregnant man. We have had dog saints and cat massacres. We possess a whole library of works on madmen, criminals, witches, and beggars. Why this penchant for the offbeat and the marginal?1

I see two explanations, one literary and one political. There comes a time in the career of many historians when they yearn for contact with the general reading public. Having won a place in the profession with a dissertation and a string of scholarly publications, they want to break out of the monographic mode. They want to write for someone besides their fellow specialists. But how to reach the general reader?

They need to find the right subject, not merely something sexy like sex itself but something that can qualify as legitimate scholarship. Sheer vulgarization will not do; it must be haute vulgarisation, and it must involve a subject that will pass with the professionals—some curious folklore from the Middle Ages, or a strange sect of the Reformation, or a bizarre custom unearthed from the archives of the Inquisition. Best of all, it should combine elements of sexuality and popular mentality drawn from manuscript sources and served up with a dash of anthropology. Le Roy Ladurie worked a miracle with that formula.2 Every historian who hungers for readers say to himself in petto: “Le Roy did it; why can’t I?”

Easier said than done; for the dilemma—how to reach readers while clinging to your scholarly legitimacy—is complicated by a further consideration, which for lack of a better word I would call political.

The new subjects bear the mark of the 1960s. Before the student movements, the Vietnam War, and the “events” of May–June 1968 in Paris, historians of the left took on large subjects—the making of a working class, the rising of a peasantry—and viewed them “from below.” Their successors in the next generation favor microhistory, case studies of the deviant and the dispossessed, which they see aslant or from the side. Marginality has emerged as both a subject and a point of view.

It has its prophet, Michel Foucault, whose voice rose over the confusion of May–June to proclaim the importance of understanding the cognitive aspect of power—power as a way of ordering reality or sorting things out so that mental boundaries operate as social constraints and give shape to institutions. The victims of history for Foucault were its displaced persons, those who did not fit squarely on the cognitive map: the mad, the criminal, and the deviant. They fell outside the boundaries of the social order; but by virtue of their marginality, they made the map stand out. They brought it within the range of perception of historians located in another social space.

The marginal therefore became the principal concern of history as a “discourse,” a way of construing a subject on the part of the professionals. This fresh sense of subject matter gave rise to a new style of writing as well as a new way of thinking. Intransitive verbs tended to become transitive. Thus according to Foucault, madness had to be thought before madmen could be consigned to a special category of humanity and set apart in cells. The history of insanity took place on epistemological ground, which led from the border areas of society to the heart of its power system.3

When other historians looked from the outside in, they, too, began to rethink the past. Inclusion and exclusion, fitting and misfitting, appeared as a historical process, and the marginal moved to the center of a discipline that began to be called a discourse. The epistemological shuffling about probably would not have had much effect in itself, except that it smelled faintly of flower power; and the generation of the 1960s was quick to catch the scent. When Foucault was still undreamt of in the philosophies of the West Coast, the margins had closed in on Berkeley. Students attempted to seize power by taking over fringe areas (People’s Park), approaching taboo sectors of language (the Free Speech Movement), and switching categories (“Make Love Not War”). With this experience behind them, and behind their counterparts on the largely symbolic barricades of Paris in 1968, Foucault made sense.

But the Sixties are gone, and Foucault is dead. We now have pop-Foucaultism, a celebration of the marginal in and of itself. The pop-Foucaultist (Foucaldien? We still lack a label.) does not pause to consider the epistemological ground of his subject. He races for the fringe, or beyond it, and rummages about until he comes up with something suitably exotic. So history is becoming cluttered with curiosities. It is losing its shape. Its center will not hold.

Advertisement

Pop-Foucaultism is a dangerous temptation for the professional seeking a public. It offers spurious intellectual legitimacy, a voguish left-wing appeal, and readers. Not that everyone who writes about madmen and criminals can be considered a follower of Foucault or that all of Foucault’s followers can be indicted for vulgarization. But vulgarized Foucault, Foucault spiced up in order to be sensational and thinned out in order to be accessible, the Foucault of pop history can serve only to trivialize history in general.

Consider the case of Damning the Innocent: A History of the Persecution of the Impotent in Pre-Revolutionary France by Pierre Darmon, a historian who entered the profession in the 1960s and is now a chargé de recherche at the French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. According to the publishers of the English translation, the book “is intended for the general reader.” According to Darmon, it is meant as a study of a neglected kind of marginality:

Among the many groups of people who suffered at the hands of the Ancien Régime in France—the insane, the poor, sodomites, alchemists and blasphemers—the impotent have long been forgotten.

Foucault and his followers had covered nearly all the marginal areas of early modern society; but somehow they had overlooked one, which Darmon made his own: impotence.

The impotent of early modern France faced a potentially humilating ordeal. If married and accused by their wives of being unable to fulfill their “conjugal duty,” they could be brought before an ecclesiastical court and challenged to prove their virility. Proof took the form of a daunting obstacle course—erection, intromission, ejaculation—which had to be negotiated before witnesses. The most spectacular impotence trials involved “congress,” that is, sexual intercourse between the spouses with a collection of midwives and surgeons hovering in the background, ready to provide expert testimony about the erectness of the penis, the dilation of the vagina, and evidence of sperm deposits.

The Catholic Church sanctioned these procedures because impotence constituted one of the few grounds for annulling marriage. Some early theologians had looked favorably upon marriages without sexual relations, “fraternal cohabitation” as it was known in one of the more exotic branches of canon law, but by the thirteenth century the Church linked marriage to procreation, and by the seventeenth century trial by congress provided one of the few ways for a wife to get rid of an impotent husband.

The husbands would seem to have suffered most from the ordeal. They certainly had most to lose: wife, dowry, and reputation. Yet Darmon sympathizes mainly with the wives. He writes from the viewpoint of a committed feminist and adopts a tone of moral indignation, so that “congress” appears as the cruelest form of domination in a “phallocentric” society.

What is phallocentrism? Darmon does not pause to explain this key idea, but he indicates that it goes deeper than penis envy, phallic worship, or similar afflictions. It is a kind of discourse. The French had always had sex, but from the late sixteenth century to the early nineteenth century—the classical period of Foucaultist research—they had “the putting into discourse of sex.” Foucault had discovered this phenomenon and had puzzled out its basic mechanism: the elaboration of “structures of exclusion,” which defined certain groups as deviant and relegated them to the margins of society.

Darmon recognized that the impotent and their wives became marginal in precisely this manner. If they did not suffer in the same way as some of their contemporaries—Protestants hanged for heresy, food rioters broken on the wheel, salt smugglers worked to death in the galleys—they deserved a prominent place among the victims of the old regime and on the agenda of Foucaultist history.

Darmon therefore set about the rehabilitation of the impotent. To Foucault he added Freud: “Deep in the shadowy unconscious of every man lurks a terrible fear of castration. The myth of virility can be seen as the sublimation of this anxiety.” Behind the myth of virility, manipulating the unconscious and “damning the innocent,” Darmon detected the principal power of darkness at work in the early modern world: the Catholic Church. By investing all of its authority in the impotence trials, the Church created an uncompromising standard of masculinity: no undersized penises, no flabby erections, no seed spilled outside the divinely ordained orifice.

According to Darmon, this policy promoted the interest of the clergy in two ways. It defended them against the imputation that they lacked virility themselves, and it provided an outlet for their “confused any murky libido” by giving them an opportunity to interfere in the sex lives of their parishioners.

Advertisement

In these circumstances, the [impotence] trial assumes the form of a sacrifice in the pagan sense of the term, in which the high-priest or judge unburdens himself of his neuroses by transferring them to his victim.

We therefore have a Voltairean gloss on a Freudian gloss on Foucault. From one end of the book to the other, Darmon vents moral outrage against the Catholic Church—its “openly misogynistic philosophy,” “intellectual onanism,” “exacerbated voyeurism,” “sadistic” delight in imposing “mental torture,” and so on. The impotence trials appear as the most evil variety of priestcraft. By causing the impotent to become marginal, they created a system of sexual enslavement.

How important were they? Darmon assures us that a “tidal wave” of impotence trials hit France in the sixteenth century, yet he found evidence of only a “few dozen” cases in the archives. That did not prevent him from attempting some quantitative analysis. Upon closer inspection the few dozen cases came down to sixteen, all of them from the period 1730–1788, in the papers of the ecclesiastical court of Paris. After working them over statistically, Darmon offers some conclusions about the average age and the socio-occupational position of the litigants. His main finding, an “astonishing predominance” (20 percent) of the nobility, seems to rest on three cases.

Normally, however, Darmon relies on a literary reading of the sources—a more effective technique than quantification because he is gifted with the ability to see through a text to the motivation of the person described in it. Thus his account of ecclesiastical cross-examining:

Admission did not put an end to the torture, for the ecclesiastical judge wanted to know everything about the evil afflicting the impotent husband. Relentlessly, and impelled by a kind of sadistic relish, he would ponder the smallest details.

This effect is heightened in the American edition, because the translator also plays tricks with the text. On page 134 the same “learned theologian” presses five prurient questions on a hapless defendant, whereas in the French edition, page 149, the questions come from different prosecutors in five different cases. The elimination of all footnotes and of most other references makes it impossible for the reader of the English text to know the sources of the quotations—a serious problem since some passages come from court archives, some from legal treatises, and some from quasi-pornographic pamphlets, all of them scattered over several centuries and often crammed into the same paragraph. Moreover, the translation frequently deviates from the original, nearly always in a way that distorts or dramatizes. Thus “procès et justification de la visite féminine” becomes “the science of misogyny.” But why fuss over niceties? History “intended for the general reader” can accommodate some hype.

And the general reader can regale himself with the anecdotes scattered liberally through the text. We are treated to: theological inquiries on holy copulation: “‘Did the Virgin Mary emit semen in the course of her relations with the Holy Spirit?”‘; papal pronouncements on erections: “‘It is necessary,’ advised the Holy Father [Pius IX in 1858], ‘to verify whether the penis is capable of a prompt erection which can last the time necessary for the achievement of coitus”‘; and all manner of details on struggles in the marriage bed: “Hubigneau asserted that his wife, Anne Gabrielle de La Motte, ‘had refused to perform her conjugal duty time after time, by adopting postures which did make it impossible for him to advance upon her.”‘ We follow the great debate about the testicles of the Baron d’Argenton, “which did withdraw inside his person when he turned over.” We learn about narrow vaginas and elephantine penises, about hermaphrodites and eunuchs, and about the effects of horseriding on pubic hair. We read recipes for faking virginity and for casting sexual spells. We take detours through the literature on the hymen (Darmon calls it a “more or less hypothetical film” but can’t seem to decide whether it exits), on the mating habits of elephants (they were believed to have such natural modesty that they copulated in private and always washed before returning to the herd), and on the cruel deflowerings of Fez (the wedding feast could not begin until the newlyweds produced a bloodstained sheet).

Some of this seems rather peripheral to the subject but then the subject belongs to the periphery. Once he makes it to the margin, the pop-Foucaultist cannot go wrong. For that is where he locates the new historical frontier, where he finds his richest lodes of material, where he feels ideologically at ease, and where he hopes to entice his readers. Caveat emptor.

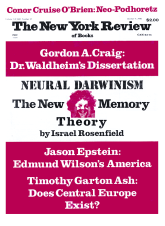

This Issue

October 9, 1986

-

1

See, for example, Judith C. Brown, Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy (Oxford University Press, 1985); Rudolph M. Bell, Holy Anorexia (University of Chicago Press, 1985); Roger Shattuck, The Forbidden Experiment: The Story of the Wild Boy of Aveyron (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980); Roberto Zapperi, L’uomo incito. L’uomo, la donna e il potere (Lerici, 1979); Jean-Claude Schmitt, The Holy Greyhound: Guinefort Healer of Children Since the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge University Press, 1983); robert Darnton. The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes of French Cultural History (Basic Books, 1984; Random House/Vintage, 1985); Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (Random House/Vintage, 1973); Carlo Ginzburg, The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984; Penguin, 1985); and Arlette Farge, Délinquance et Criminalité: Le Vol’d Aliments à Paris au XVIIIe Siècle (Paris: Plon, 1974). ↩

-

2

Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, Montaillou: The Promised Land of Error (Random House/Vintage, 1979). ↩

-

3

See Foucault, L’ordre du discours (Gallimard, 1971). ↩