Eyes Wide Shut, the thirteenth and last feature film directed by Stanley Kubrick, who died on March 7, is based on Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle, which was published in 1926. Schnitzler’s story is set in turn-of-the-century Vienna and Kubrick’s movie is set in contemporary New York City, but otherwise the adaptation is pretty faithful. A successful doctor and his wife, happily married and with a young daughter, go to a party one evening where they are flirted with, separately, by attractive strangers. The doctor, at one point, is called away by the host to minister to a young, naked woman who has overdosed in an upstairs bathroom. When the doctor and his wife get home they discover that the experience has aroused a sexual passion that had become semi-dormant, and their renewed intimacy inspires the wife to confess to an intense but unconsummated infatuation with a man she had glimpsed briefly at a vacation spot the previous summer.

The doctor is a little shocked by his wife’s revelation; he had not imagined her capable of deception, or of a desire not grounded in domestic affection, and he is in the middle of sorting out his feelings when he is called to the house of a patient. This begins a series of erotic misadventures which take up the rest of the doctor’s night, culminating in his appearance, in disguise, at an orgy where all the participants are masked. He is found out and threatened with death, but one of the orgiasts, a beautiful woman, pleads for his life, offering to accept his punishment herself. The doctor is allowed to flee. The next day, he retraces his steps to see if he can learn the identity of his deliverer, but he is continually frustrated, and he ends by finding, in a morgue, the body of a woman who has died under mysterious circumstances. We later gather both that she was the woman he had earlier treated and that she might have been the woman at the orgy. He goes home again to his wife, who has been having her own erotic nightmares, and, shaken by their exposure to the libidinal nightworld, they reaffirm their commitment to each other and to nice safe marital sex.

Kubrick at one point reportedly planned to film this story as a comedy, and thought of casting Steve Martin as the doctor. But he eventually signed Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, no comedians, to play the doctor and the doctor’s wife; and he instructed his screenwriter, Frederic Raphael, to stick close to the Schnitzler novel, which is a fairly earnest piece of Weimar-era Freudiana. Raphael and Kubrick spent more than a year on the script, beginning in 1994; shooting took another year. The result, in spite of everything, is pretty funny.

Kubrick had a reputation for remorseless intelligence. He knew what he wanted (or, which was just as valuable for his purposes, what he didn’t want), and he had set things up in such a way—he lived, after 1968, more or less in seclusion with his family on an estate in England—that he could get it out of the people he worked with simply by wearing them down. He had a lot more time than they did, and only the one thing on his mind. Kubrick was an expert chess player—when he was a young man scrounging a living in Greenwich Village, he is supposed to have hustled chess matches in Washington Square Park—and he seems to have seen the business of filmmaking in terms of chess combinations: every move set up another move, with the goal always a little bit beyond the other player’s grasp.

People figured this out pretty quickly; there was nothing underhanded about it. Some, such as Diane Johnson, who wrote the screenplay for The Shining (1980), and Michael Herr, the chief screenwriter on Full Metal Jacket (1987), appreciated the brains, had much affection for the man, and enjoyed the contest. Others, for example Raphael, who felt that Kubrick feigned admiration for his intellect just to get a script out of him and then rejected all his ideas, resented it.* Actors often resented it, too; Kubrick was notorious for requiring dozens of takes on a scene without ever specifying what he was looking for. But people who have testified about it tend to agree that when everyone was trying to figure out how to make something work, Kubrick had a knack for seeing a little farther around the corner. After the success of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), he commanded ample budgets and was allowed to take as much time as he liked to make his pictures. He had final say on everything, right down to the size of the ads; he apparently required very little sleep; and he was a perfectionist.

Advertisement

So it’s odd that all the movies Kubrick made after 2001 are obviously flawed, and not in trivial ways. They are technically scrupulous, visually innovative, conceptually upscale entertainments, each riven by some glaring and seemingly elementary misjudgment. Viewers accepted the mystifications of 2001 (though they were mostly just a lot of loose plot elements) as the kind of messianic hyperbole appropriate to sci-fi extravaganza in the Age of Aquarius. But what was Kubrick thinking when he egged Jack Nicholson on to give his self-parodying performance in The Shining, in which Nicholson all but moons the camera? Or when he cast an overmatched Ryan O’Neal—who wears, throughout the picture, the expression of a man concentrating very hard, but with distressingly uneven success, on the requirement that he deliver his lines with an Irish accent—as the hero of Barry Lyndon (1975)?

How could Kubrick have been shocked (as he claimed to be) that audiences for A Clockwork Orange (1971) identified with the sociopathic Alex, since he had taken such pains to portray all of Alex’s victims as sickos, hypocrites, and dimwits? What made him imagine that he could salvage a shred of pathos after devoting the first forty-five minutes of Full Metal Jacket to an obscene tirade by Lee Ermey in the role of a Marine drill sergeant, a character American movies had ground into cliché long before? The enjoyment of a Kubrick movie (and there has always been plenty to enjoy) has required a willingness to blink at miscalculations that any mere Hollywood mortal, quivering under the lash of a philistine producer, would have known better than to leave in the picture. Kubrick’s mistakes were the kind of mistakes only a genius (or possibly, as Pauline Kael once suggested in a review of Full Metal Jacket, only somebody who thought he was a genius) could make.

Eyes Wide Shut is different. In Eyes Wide Shut nothing works. There were two ways to film Schnitzler’s story: as a dream (as its title invites) or as straight drama (the form its narrative actually takes). For many directors the dream mode would have been the trickier option, but for Kubrick the risks were all in the other direction. He did not make his career on straight drama. He more or less pitched overboard whatever interest there might have been in the love story in Lolita (1962) and turned the picture over to Peter Sellers to improvise what is essentially just inspired schtick. Dr. Strangelove (1964), his one flawless movie, was all schtick, but that was the idea. He shot from the Martian point of view: he coolly spied on earthling folly. He was famous for histrionics—the “Singin’ in the Rain” sequence in A Clockwork Orange, Jack with the ax in The Shining—but he was in fact brilliant (like Antonioni, who was surely an influence) at capturing a certain deadness in human relations, as in the opening of The Shining, when Jack is shown around the hotel, or the astronauts’ dialogue in 2001, or almost every scene in Barry Lyndon. He did not have a middle register.

It was therefore a mistake to have given Cruise and Kidman a lot of acting to do. Cruise is a star; the camera loves him. But he is not an actor with a lot of range. Kidman is an actress, but she is not a star. She is a pretty and somewhat pinched woman, with a flat voice, who gives the impression of working very hard. This story was beyond their talents. Kubrick might have carried them by giving them some business, some music, some banter. But most of the way they are on their own, working with dialogue made of wood.

Kidman’s big scenes come near the beginning—when she is picked up by the handsome stranger and, later on, when she confesses her temporary infatuation to her husband. (His name in the movie is Bill; hers is Alice.) At the party Alice is supposed to be a little giddy—we see her drinking a glass and a half of champagne—but Kidman plays the scene as though she were nearly drunk, slurring her sentences and lolling her head stupidly. In the later scene (which she is made to do walking up and down in her underwear while Cruise sits demurely on the bed) she is required, at one point, to fall to the floor while laughing derisively. She really gives it, in what was plainly the ninety-ninth take, an earnest effort. (And she will probably win an Academy Award.)

Cruise has an easier chore, since it is important that the doctor be somewhat phlegmatic. Bill’s night in the underworld is supposed to crush him, though, and Cruise’s body does not register defeat. He can be stunned, angry, exasperated; but he cannot lose his robust self-esteem. That’s where the star power comes from. In the end, Bill is supposed to break down and sob while clinging to his wife. Tom Cruise does not do a convincing sob.

Advertisement

The publicity for the movie has concentrated obsessively on the fact that Cruise and Kidman are married, with the hint that this can be expected to give their sex scenes some sort of hormonal boost. In fact, they have no sex scenes with each other, apart from a brief kiss, and anyone who has seen them together on television—for example, at an awards ceremony—suspects that in real life they have no chemistry. Their marriage may be perfectly happy and sexually fulfilling, or it may be a Hollywood mariage blanc. Who cares? It doesn’t matter, because they have no chemistry in the movie, either. Kubrick has Bill and Alice smoke a joint before they get into their argument in the bedroom; this ratchets the scene down to a farcical slow-motion, but it may have been a way of giving his actors a pretext for simulating familiarity.

The rest of the movie is fakery of a kind so half-baked that the audience at the preview I attended couldn’t stop giggling. The man, played by Sky Dumont, who flirts with Alice at the party is a silver-haired lothario who begins by picking up her half-finished champagne glass and swallowing the rest of the drink while looking her suggestively in the eye. Real suave. Then he says things like, “Have you read Ovid, the Latin poet?” She finds this irresistible.

Dumont doesn’t have just one cheesy line. He has six cheesy lines (“Do you like Renaissance bronzes? I love them”), plus a Hungarian accent. Every scene runs five minutes over. It takes fifty minutes to reach Bill’s nocturnal adventures, which are, after all, the heart of the story. His initial encounters (with the daughter of a patient, with a prostitute, in a shop where he rents a disguise for the orgy) are performed on a set dressed up to look the way New York looked about twenty-five years ago (dangerous and seedy). These scenes are stagy and banal enough, but it is the orgy that achieves true bathos.

In an English castle out in decadent Glen Cove, as a hidden choir drones in Latin (or something), Bill watches a masked and red-robed anti-pope swing a censer in the middle of a ring of kneeling supermodels (identical proud firm breasts, straight hair, no hips) wearing only masks and black thongs and looking extremely chilly. (None of this is in Schnitzler.) Each supermodel then pairs off with one of the dozens of caped and masked men who have been observing this incomprehensible ritual. Cruise, also masked, is picked up by one of the women, and they have a conversation, which, since you cannot see their lips move, is exactly like watching a Japanese gangster movie dubbed into English. The woman is whisked off by other cloaked figures, and Bill wanders around the castle, running into scenes of masked men humping mechanically away at naked women draped over coffee tables while other orgiasts huddle around watching (and carefully blocking our view of anything that might give Warner Bros. a rating problem). The soundtrack is an instrumental version of “Strangers in the Night.” It is a very tacky orgy.

Later, we learn that these orgiasts are, yes, important and powerful men (who evidently require the stimulation of a phony black mass before being able to engage in sex with supermodels). This information is given to Bill by one of his patients, a rich New Yorker played by Sidney Pollack, who summons him at the end of the film to explain what he has stumbled onto. It is an interminable scene (also with no counterpart in Schnitzler) that muddles the plot by suggesting that the woman at the orgy was also the woman who had overdosed at the party. This gratuitous effort at continuity kills any ambiguity about whether Bill’s experience has been a dream. The whole scene is played as though the actors were underwater. The acting is so deliberate, in fact, that one wonders whether the scene was not a blocking rehearsal.

And this leads to the inevitable impolite question, which is whether Kubrick really had finished the movie before he died, as Warner Bros. and the Cruises have loudly insisted. Kubrick was exactly the kind of director who continues to drive everyone crazy with changes right up to opening night. It seems strange that he considered finished at the beginning of March a movie not scheduled for release until July. The movie runs at least twenty minutes too long, and music seems ill-matched to many scenes. Danger is signalled by repeated strikings of a high note on the piano—PING PING PING PING. It is hard to imagine that Kubrick, who had uncommon musical instincts, would have used this device so obtrusively. And there are many uncharacteristic slips, such as dialogue in which minor characters slide unexpectedly into British accents. The nighttime street shots look like stock footage. The whole thing needed another month in the shop.

Not that it would have made much difference, given the wisdom of the people who made it. They became inflated by their own hype: Cruise, Kidman, Kubrick, years in the making, the work of a master, SEX. The story of a respectable man who tumbles into an erotic underworld and finds himself trying to escape his own fantasies might seem a challenge for anyone to film; but in fact it had already been done, by Martin Scorsese, in After Hours, starring Griffin Dunne—a movie that is well-written, unpretentious, masterfully directed, and a comedy.

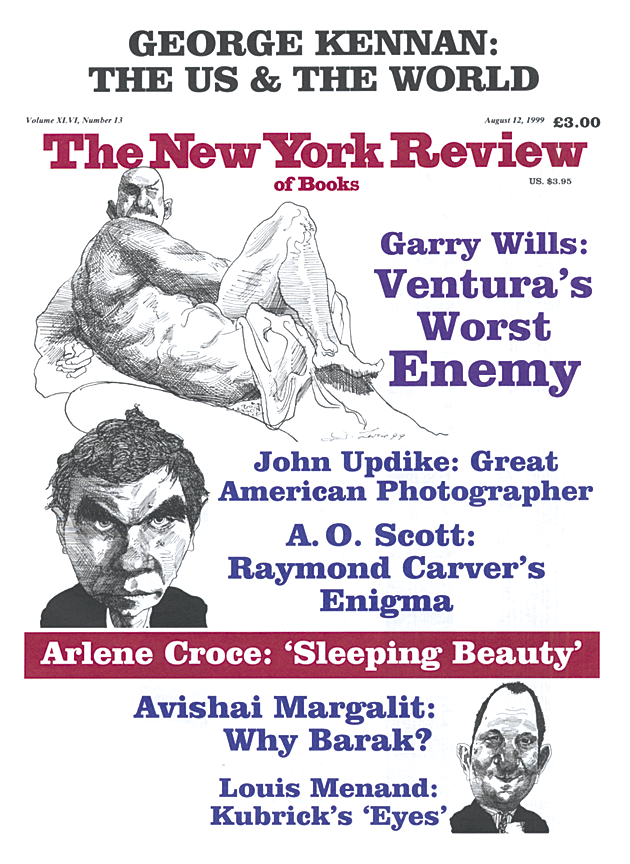

This Issue

August 12, 1999

-

*

Johnson’s brief eulogy appeared in The New York Review, April 22, 1999; Herr’s exquisitely written profile (which, characteristically, Kubrick arranged with the magazine before informing Herr that he was to write it) is in the August issue of Vanity Fair. Raphael’s self-serving memoir, Eyes Wide Open, is published by Ballantine. There are two recent biographies: Vincent LoBrutto’s Stanley Kubrick:ABiography (1997; reprinted by Da Capo, 1999) and John Baxter’s identically titled book (Carroll & Graf, 1997). Baxter mentions that Kubrick was probably drawn to Raphael’s 1971 novel, Who Were You With Last Night?, an extended Schnitzleresque male erotic fantasy. Raphael, for whatever reasons, chooses to represent Kubrick’s solicitation as a bolt from the blue. ↩