1.

Barry Goldwater loved ham radio and liked to fly airplanes, was a fine photographer, had a lifelong subscription to Popular Mechanics, inherited a share of his family’s department store, and as a retailer became celebrated as the creator of “antsy-pants,” men’s boxer shorts imprinted with drawings of ants crawling this way and that. He was a man’s man, a guy’s guy, a regular fellow. Big, handsome, square-jawed, quick to smile, easy to like. A straight-from-the-shoulder talker who’d rather tinker with his old souped-up car than go to a black-tie dinner.

Make him a presidential candidate running against the shrewdest politician who ever cut a deal, and you have a movie by Frank Capra: Mr. Goldwater Runs for President. Capra’s Goldwater of course would have won. American innocents were Capra’s specialty, and they never lost. Whether they went to whorish, thieving Washington like Mr. Smith or went to town playing the tuba like “pixillated” Mr. Deeds, they prevailed. In Capra’s America innocence could never be defeated.

The real Goldwater was not quite so innocent as that. He surely knew all along that he was going to lose to Lyndon Johnson in 1964. Anybody who ran against Johnson was probably going to lose that year, because Johnson held a nearly unbeatable hand. People who watched Goldwater campaign suspected, however, that he was a little too resigned to losing, that maybe he really didn’t want to win. One afternoon while campaigning by train in the Middle West he climbed into the engineer’s cab, took control of the locomotive, and hauled his own rented train across the prairie. That was not what a man did who had “fire in the belly,” as the reporters called the consuming lust for presidential power; it was Goldwater the Popular Mechanics subscriber extracting at least one boyish adventure from this miserable experience.

Long afterward Goldwater wrote that he had been “better equipped, psychologically” for military life than for politics. “If I had my life to live over again, I’d go to West Point,” he said in his autobiography. Well, he was nearly eighty when he wrote that and maybe losing touch with the man he had been when young. The evidence suggests he would not have flourished under military discipline. As a young Republican senator he once attacked a Republican president, a five-star general named Eisenhower, for operating “a dime-store New Deal.” Such insubordination spoke of a man more passionate about politics than discipline.

Perhaps he was one of those politicians who are born not to command but to preach crusades. He was a good talker, but not much for doing. “Lazy” was the judgment of reporters who covered him in the Senate. When he talked, though, audiences cheered and opened their checkbooks.

The gospel he preached was “conservatism.” Forty years ago it was a word no politician had spoken, except with contempt, since the age of the Hoover collar. Nowadays of course politicians fling it about with the same reverence accorded “home” and “mother,” but by the late 1950s Goldwater was saying “conservative” with a bravado that unnerved many Republicans and roused many more to a fresh passion for politics. His 1964 campaign was to bring the word out of shame and darkness. Despite his humiliating defeat, “conservatism” soon became the battle cry of shrewd and angry political newcomers who gutted the old Republican Party and rebuilt today’s model on a foundation of Sunbelt millions, old-time religion, and white Southern solidarity.

Rick Perlstein’s richly detailed history, Before the Storm, makes it clear that Goldwater was pathetically and sometimes comically out of his depth as a presidential candidate. We revisit the fiasco of his acceptance speech and his choice of upstate New York congressman William Miller, a man unknown outside the party and unloved within, as his vice-presidential candidate. Instead of trying to heal wounds created by the nasty struggle for the nomination, Goldwater goes along with a convention eager to shoot the wounded. This ensures an enduring party split while treating a na-tional television audience to a hair-raising spectacle of conservatives as a dangerous mob howling at Nelson Rockefeller.

Finally, in an act of supreme folly, he refuses to give control of his campaign to F. Clifton White, the brilliant political technician who has got him the nomination, and hands it instead to some unqualified friends from back home in Arizona.

Only a liberal with a heart of stone can take pleasure in Goldwater’s anguish: he was a decent man trapped by events in the wrong job. Six years later, Perlstein notes, Goldwater described his 1964 role in a way suggesting he thought of himself as a victim of history:

Very early in the [1960s] I found myself becoming a political fulcrum of the vast and growing tide of American disenchantment with the public policies of liberalism…. It is true that I sensed it early and sympathized with it publicly, but I did not originate it…. I was caught up in and swept along by this tide of disenchantment.

As Perlstein observes: “There it was: controlled by events, following others’ call, a horse to be ridden.”

Advertisement

But there was no other horse available. The point to remember about Goldwater is that he was all there was. In 1964 Ronald Reagan had not yet reinvented himself as the most charming politician since Franklin Roosevelt. Except for Goldwater, not a single conservative Republican was a remotely plausible presidential candidate. Inept he may have been and lacking in guile, but he was at least presentable. The Senate had a large group of conservative Republicans until the 1958 elections, when the spread of television campaigning tempted them to show themselves on camera. Their audiences must have found them painful to the eye, for nearly all were turned out of office, and Democrats took the Senate by a landslide.

Judging a politician by his looks may be absurd, but the fact is undeniable: a nifty profile and a cheerful countenance carry great weight with American voters. Conservatism in those years seemed to afflict its leaders with hard and angry faces. Goldwa-ter was the exception. He had the smile of a genial neighbor. When he became angry it was not the silent fury of the John Bircher who believed President Eisenhower was a crypto-Communist; it was the exasperated cry of a man telling the world he’s mad as hell with bureaucrats interfering in his business and he’s not going to take it anymore.

Perlstein’s book begins with the people who recognized Goldwater early in the game as the only possible candidate and set out to snare him. Clarence Manion, the disillusioned New Dealer who had become dean of the Notre Dame law school, gets a great deal of attention. So do William Rusher and William F. Buckley, founders of the National Review, which was to become the intellectual showcase for Goldwater-style conservatism.

The tempting of Goldwater is told in detail. Goldwater resists, then only pretends to resist, then finds he has a taste for the thing, gradually starts to relent, but protests and protests as every manipulation moves him deeper into the campaign. L. Brent Bozell, Buckley’s college classmate, rushes to patch together a book from Goldwater’s old speeches. Goldwater, having left college after his freshman year and lacking both the skill and the appetite for composition, cannot be expected to write his own book, and a conservative candidate needs a book expounding his conservative ideology. Bozell gets it written. Titled The Conscience of a Conservative, it becomes a best seller.

Whether the book is more Bozell than Goldwater is unclear. Perlstein says Goldwater “skimmed Bozell’s manuscript and pronounced it fine.” Read today, it speaks with an innocent brashness rare in American politics. It assumes that American society is in a dangerous decline because Republicans as well as Democrats have lost respect for the Constitution and refuse to take the simple, if radical, steps necessary to make America whole again.

The conservative’s goal, it states, is to provide “the maximum amount of freedom for individuals that is consistent with the maintenance of social order.” And so, for example, the conservative would abolish farm subsidies, thus freeing the farmer to share the same free-market challenges that other Americans face. The conservative would abolish the graduated income tax and restore equality by taxing everyone, pauper and Croesus, at the same rate. The federal government would stop “profligate” spending projects, including social welfare, education, public power, public housing, and urban-renewal programs.

While Goldwater always personally endorsed school desegregation, his book maintained that the Supreme Court had no constitutional power to order it since education was the exclusive province of state and local governments.

In foreign policy, the book foresaw Soviet communism winning the cold war because a “craven fear of death” had entered the American psyche. America was easily bullied because it was too afraid of nuclear war. Here came a burst of bellicose prose of the sort Democrats would gleefully exploit: “We must—as the first step toward saving American freedom—…make it the cornerstone of our foreign policy: that we would rather die than lose our freedom.”

That Goldwater won the nomination despite this assault on the status quo may simply mean that Americans don’t take campaign books seriously enough to read them closely. Whatever the case, its unorthodoxies did not raise serious problems for Goldwater until the nomination was well in hand.

In Perlstein’s telling, the hero of the nomination campaign was F. Clifton White. It was White who first saw that the Republican nomination was available for the taking by whoever could master “the occult process” by which Republicans chose their candidates and their “Rube Goldberg– like system” for selecting convention delegates.

Advertisement

White was less interested in ideology than in the calculus of practical politics. A quiet back-room operator from upstate New York, he received his elementary political education in the 1940s while being outmaneuvered by Communists during a struggle for control of a veterans lobbying group. He became fascinated by the mechanics of acquiring power through democratic process. Why he signed on to elect Goldwater is unclear. Maybe he simply wanted to see if he could pull it off.

White’s strategy assumed a force of Goldwater supporters more passionate about “saving Western Civilization” than about getting patronage rewards, Perlstein writes.

Their work would begin at the dewiest grassroots level, recruiting and training candidates to stand for election to the precinct conventions; those people, in turn, would select delegates to county conventions; these, finally, would choose the national convention delegates.

States that wanted favorite-son nominations were to be encouraged.

A favorite-son delegation could become a powerful Trojan horse if all the members were really gung-ho for Goldwater. Sometimes it paid to look weak. That made you more intimidating once you proved yourself strong.

It was just as Clif White learned from the Communists—and also from John F. Kennedy’s Irish Mafia, who had started working the precincts shortly after the 1956 [Democratic] convention. A single small organization, from a distance and with minimal resources, working in stealth, could take on an entire party.

Lisa McGirr’s Suburban Warriors affords a rare picture of the grass-roots process actually working at a specific site very much as White had envisioned it. McGirr’s setting is California’s Orange County, which became America’s most celebrated conservative stronghold in the 1960s. Its fame came from its reputation for being what Fortune magazine called political “nut country.” (Its congressman James Utt made news in 1963 by suggesting that “a large contingent of barefooted Africans” might be training in Georgia as part of a United Nations military exercise to take over the United States.) McGirr’s book provides a valuable scholarly analysis of the demographics, culture, and history that made the county distinctively “conservative.”

At the start of the Goldwater movement the county was a place of white middle-class suburbanites recently settled into new tract housing developments. Its people were well educated, held high-tech jobs, and tended to see their prosperity as the result of entrepreneurial economics, despite Southern California’s dependence on the federally financed military-industrial complex. Many were migrants from Midwestern states that had been “steeped in nationalism, moralism, and piety.” They tended to think the republic was in political, economic, and moral decline, and to blame the liberal tradition for it.

McGirr’s account suggests an old-fashioned, Midwestern, small-town culture resettled in a dynamic new consumer society by the Pacific. While acknowledging that Orange County had bizarre aspects, she suggests that basically it was as American as Warren G. Harding dreaming of a return to “normalcy.” Liberals who experienced Orange County passion first-hand may think it was not quite so pastoral.

White started working on the Goldwater nomination in 1961. When the Republicans assembled in the San Francisco Cow Palace in the summer of 1964, he had beaten the once formidable moderate Northeastern establishment which had ruled party conventions seemingly forever. That summer its leaders included former President Eisenhower, the all-purpose Massachusetts aristocrat Henry Cabot Lodge, and Governors Rockefeller of New York, Scranton of Pennsylvania, and Romney of Michigan. They had fretted, fidgeted, and fought indecisively among themselves all year about who the nominee should be. They were backing Rockefeller when a baby was born to his new wife on the eve of the California primary. This revived at the worst possible moment the scandal of his divorce, and two days later Goldwater won the California election. There was a futile last-minute attempt to stop Goldwater by rallying a coalition behind Scranton, and White easily snuffed it out.

Perlstein’s account of what happened next is an ancient tale of triumph as the father of disaster. In this supreme moment Goldwater had an acceptance speech to give. After such a nasty convention, precedent called for a conciliatory bromide about burying anger in brotherhood and marching onward to the White House. Goldwater didn’t feel like doing that.

He and his closest advisors rejected conciliation. They thought that neither Scranton nor Rockefeller deserved conciliation. Goldwater asked for a draft speech from Harry Jaffa, a political science professor and Abraham Lincoln expert from Ohio State University who held that if Lincoln were then alive he would call himself a conservative.

Perlstein says Jaffa wanted to do something with the word “extremism.” Democrats were using it to make voters think Goldwater was a war-crazed wild man too reckless to be trusted with the nuclear button. “Goldwater was sick of the word.” His “brain trust,” as Perlstein calls them, quarreled over one of Jaffa’s lines. Too incendiary, some argued. Goldwater liked it. He ordered it underlined twice. Thus the origin of the most famous speech of the campaign.

The text of the finished speech was so closely held that Goldwater’s chief political strategists, including White, were not allowed an advance peek, for fear that would “raise hell,” says Perlstein. Nowadays Goldwater’s underlined words seem nothing more than a bland philosophical observation that a good cause is better pursued with “extremism” than with “moderation”: “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty—is—no—vice!” A roar of approval interrupted him for forty seconds. Then: “And let me remind you also—that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue!”

Gentle philosophizing was not what Goldwater had in mind. He knew very well that “extremism” and “moderation” were explosive words that year. He was telling the party that he had no interest in trying to preserve the old middle-of-the-road consensus. He was telling the “moderates” they could choke on their own frustration.

“A cultural call to arms,” Perlstein calls it. Hearing it for the first time in his command trailer outside the hall, “White was so disgusted with what he could see only as a political disaster that he switched off his television monitor in rage.”

There was a standing ovation in the hall. “Richard Nixon, making a snap political judgment, reached over to keep wife Pat in her seat. He was sick to his stomach.” Scranton “glowered.” A Goldwater man telling Romney he hoped the party would unite for victory “got back nothing but a bitter stare.”

Next morning White learned from somebody who had heard it from somebody else that he was being removed from command of the campaign. The job went instead to Dean Burch, an Arizona liability lawyer whose only political qualification was friendship with the candidate. “Like a man on his deathbed,” Perlstein writes, Goldwater “wanted to be surrounded only by friends.” The Arizona amateurs were now in charge.

There were other factors that made a Johnson triumph nearly certain. The country was less than a year removed from the Kennedy assassination and only two years from the Cuban missile crisis and its close brush with nuclear war. The public was in no mood for the new excitements that would come with installing yet another president. Moreover, Johnson had done a masterful job of managing the transition after Kennedy’s murder. With astonishing skill and speed, he had got through Congress a domestic program more ambitiously liberal than that of any president since Franklin Roosevelt. He cleverly exploited Goldwater’s talk about atomic bombs, extremism, and tougher policies toward communism to paint Goldwater as a wild man.

For the first time in a long career Johnson found himself a beloved political figure. Until now his reputation had been that of a slick Texas wheeler-dealer, but that fall the public took to him with astonishing enthusiasm:

People’s response to seeing Johnson in the flesh was primal. Sometimes security men used their fists to keep crowds from smothering the President; sometimes they had to reach for their guns when rope lines snapped. Everywhere it was the same: people packed shoulder to shoulder as far as the eye could see. The President stood on his limousine seat and seemed to float above the crowd….

In the spectacle liberal intellectuals spied Newtonian perfection: the pull toward consensus, the push away from extremism, a system regressing toward a safe, steady equilibrium…. Their young ruler had died, and they reached out to the new one with raw, naked need, to fill an empty place, as if with his touch he could, just as he promised, let us continue, as if the bad things hadn’t happened at all.

He was reelected with the biggest percentage of the vote ever. It was a triumph as exhilarating as Goldwater’s had been at San Francisco, and, as with Goldwater, it was the father of disaster.

With the election won, Johnson waded deeper than ever before into the Vietnam War. Later the Pentagon Papers revealed that the administration had been planning all along to intensify the war. All along, while Johnson was declaring himself the peacemaker, plans for expanding the war were secretly being prepared. Exultant in political victory, Johnson proceeded to bomb, then to send more soldiers, then… Four years later his ruin was so complete that he surrendered the White House without trying to win a second term.

2.

Did the 1964 campaign really start something epochal? Perlstein says it “lit the fire that consumed an entire ideological universe, and made the opening years of the twenty-first century as surely a conservative epoch as the era between the New Deal and the Great Society was a lib-eral one.” Recent political history suggests something a bit less cosmic has happened.

True, we are now governed by history’s first court-appointed administration, thanks to five justices of the Supreme Court who are indeed conservatives, and the beneficiary of their intervention calls himself a “compassionate conservative.” For the rest, though, conservatism has not run very well lately when put to the vote. Compassionately conservative Bush finished second behind Gore in the national popular vote. Conservatives lost control of the Senate, and the Republican majority in the House of Representatives was reduced to a wisp.

Conservatism itself seems to have turned into something quite different from the conservatism of 1964. The Supreme Court’s taking charge of the presidential election last December was a spectacular example of what conservatives of the Goldwater era used to deplore as judicial activism, a supposedly liberal vice.

Here is another eerie development: conservatism, which in Goldwater’s day was unshakably committed to balancing the budget and reducing the national debt, managed to outdo two generations of liberal big spenders by quadrupling the debt during the twelve years of Reagan and Bush the Elder. And now we have the conservative younger Bush making a Keynesian argument for cutting taxes. In Goldwater’s day conservatives regarded John Maynard Keynes’s economic theories as only slightly less seditious than Karl Marx’s.

One could go on listing strange mutations in conservatism since Goldwater—the rise of the clergyman as political boss, for instance, as with the Reverends Robertson and Falwell. What all this illustrates is the futility of discussing ideology with today’s shopworn vocabulary. Words like “conservative”and “liberal” now mean whatever anybody saying or writing them wants them to mean. Wasn’t it a Supreme Court justice who said he couldn’t define pornography, but he knew what it was when he saw it? “Conservative” and “liberal” are like that. Where Perlstein sees the present political environment as a “conservative” epoch, it can be just as easily argued that an electorate unable to choose between Bush and Gore, far from blazing an ideological trail to the right, is drifting tranquilly toward slumber.

For most of the twentieth century American politics adhered to centrist ideas. Occasionally, as during the Depression, the country moved decidedly left; occasionally, as during the 1980s, decidedly right. The center, however, was traditionally the ground to seize and hold for politicians who wanted to win. By the time Clinton was elected the center had drifted rightward, and Clinton acknowledged this. Dukakis and Mondale had not, and had lost two presidential elections. Clinton may have won only because Ross Perot split the Republican vote in 1992, but once in office he acted on the assumption that the country had run out of enthusiasm for doing good and wanted to taste the pleasures of doing well.

Nudging Democrats off their traditional left-of-center ground, he moved them into the vacant trenches formerly occupied by “moderate” Republicans, a nearly extinct species, thanks to the conservatives’ efforts to purge the party of impure ideas. There, dug in slightly to the right of the late Nelson Rockefeller, Democrats rediscovered the rewards that normally accrue to American politicians holding the middle of the road. They might be enjoying them still but for the importunate Monica Lewinsky and Gore’s curious inability to find out who he was.

The middle of the road was where both parties had traditionally thrived while fighting over the distinctions between tittles and jots. In America the middle ruled. People who moved out of it, leftward or right, were deplored and scolded as “extremists”—deplored because leaving the middle led so often to defeat, scolded because extremism had been made to seem radical and un-American. That was the burden of Johnson’s attack on Goldwater: he was an extremist and extremists were bad.

Senator Robert A. Taft, conservatism’s tragic hero, had argued against the centrist consensus long before Goldwater’s time. Taft believed there was a big conservative vote which never went to the polls because Republicans never chose a truly conservative presidential candidate. William Buckley, with his gift for blood-stirring prose, turned Taft’s argument into a challenge to combat: “Middle-of-the-road…is politically, intellectually, and morally repugnant.”

Perlstein’s subtitle, “Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus,” alludes to the Republican departure from middle-of-the- road politics in 1964. He is not persuasive, though, in arguing that this ended the consensus. To be sure, signs of new life appeared soon after the defeat, and the word “conservatism” lost its stigma. Candidates began calling themselves “conservatives” and winning lesser elections, and sometimes bigger elections. Ronald Reagan became governor of California.

Yet the sixteen years between Goldwater’s defeat and the start of Reagan’s presidency produced no notable reversal of the “big government” domestic policies rooted in the New Deal. In those years Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter continued strengthening the welfare state. By the time Reagan arrived it had become such an entrenched part of American life that the Reagan people trying to root it out thought of themselves as revolutionaries, rather than conservatives. Conservatives are supposed to preserve tradition, not destroy it. They might have more correctly called themselves reactionaries for they were people unresigned to long tradition and were fighting to destroy a political culture their parents and grandparents had hated since Peter Arno cartooned them in 1936 going to a newsreel theater “to hiss Roosevelt.”

Reagan himself was anything but reactionary. He had firmly held ideas about changes he wanted in foreign and economic policy. Dismantling the welfare state was not a high priority. He cautiously avoided assaults on Social Security and health care programs. While talking eloquently about the importance of school prayer and the rights of the unborn, he did nothing of consequence to restore classroom praying or end abortion, possibly because his polls showed these were losing issues.

And so the right’s glorious Reagan years ended with some of its most passionately held goals still unreached. The right was uneasy about the succession of the elder Bush. Conservatives were people of sunny southlands, and though he claimed to like pork rinds, Bush came from the same Northeastern, Ivy League, internationalist, Wall Street crowd that had sulked on the sidelines while Goldwater was being humiliated by Johnson. Worse than that, he raised taxes!

If the senior Bush was hard for conservatives to suffer, Bill Clinton drove them near to madness. The history of their attempts to destroy Clinton and their constant failures to do so is a garish tale of politics as pathology. Clinton’s ability to defeat them time and again while governing in accord with the hated old moderate-Republican reliance on consensus mocked the notion that conservatism had won a great ideological victory. Clinton demonstrated that consensus remained as powerful as it had been before Goldwater.

If ever an epoch of conservatism seemed at hand, it was when the 1994 elections gave Newt Gingrich command of the House of Representatives. The moment was brief. Gingrich attempted a conservative Putsch against Clinton, Clinton emerged triumphant, and Gingrich disappeared from public life. Encouraged by the sex scandals, conservatives tried impeaching Clinton. Without the votes to convict him in the Senate, they succeeded only in producing an unusually high public-approval rating for his presidential performance. The public did not like his vulgar sexual behavior, but it clearly liked government by centrist consensus more than government by an angry right.

3.

Modern conservatism owes much of its success to the aggressive political activity of evangelical Christian churches. In Goldwater’s era they stayed out of politics; now they crack whips. When young Bush needed a primary-election victory over John McCain in South Carolina last year, he did his duty to the church by speaking at Bob Jones University, famous as an intellectual citadel of the racially segregated life. McCain, realizing that the Christian right was about to do him in, lost his temper, spoke angrily about the tactics of certain political churchmen, and so assured Bush of a big victory.

This was a far different conservatism from Goldwater’s 1964 variety. Like Calvin Coolidge, Goldwater believed that the business of America was business. Today’s conservatism, heavily influenced by a Christian fundamentalist vote, holds that the business of America is also morality. The result is a politics passionately devoted to argument about family life, abortion, religion, and sex.

The history of the evangelical entry into politics is fascinating and complicated. There is an excellent account in Right-Wing Populism in America, by Chip Berlet and Matthew N. Lyons, whose book describes the outermost fringes of American conservatism. The story involves the Book of Revelations, Satan, the Antichrist, the End Times—a period of widespread sinfulness, moral depravity, and crass materialism—and disagreement among Premillenialists about whether faithful Christians will experience no Tribulations, some Tribulations, or all Tribulations. The history of how all this led these austere Protestants to enter the house of conservatism is intricate, absorbing, and worth studying by everyone who enjoys sounding off against the Christian fundamentalists and wishes he knew something about them.

Equally important to conservative success has been the disappearance of the white Democratic vote in the South. This began with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Bill. Johnson, who masterminded its enactment, said at the time it would be the end of his party in the South. To his credit he signed it anyhow and proved himself an accurate prophet. White Southern Democrats vanished fast, some because they tried to remain Democrats, others because they quickly underwent party-change surgery and turned into Republicans. This gave us today’s Dixieland version of the party of Lincoln as the party of Trent Lott and Tom DeLay.

It would be silly to pretend that racism is not a factor here. Racism has always been the unmentionable guest at conservatism’s table. Conservatives insist it is principle, not bigotry, that compels them to oppose civil rights bills, affirmative action, and all such soft-hearted and fuzzy-minded attempts to equalize the distribution of America’s boons. Whatever the explanation, the South that had been solidly Democratic so long as Democratic presidents let Jim Crow flourish became solidly Republican after Democrats became identified with civil rights causes.

Goldwater would doubtless have embarrassed today’s conservatives. He had never liked mixing religion in politics and thought government had no business legislating on moral issues. When he was eighty-five and long out of politics, he lent his name to gay rights activities and spoke out on behalf of gays in the military. One of his grandsons was homosexual. People have a constitutional right to be homosexual, he told the Washington Post reporter Lloyd Grove. He had just backed a Democrat running for Congress against a Christian conservative, and he spoke tartly of “fellows like Pat Robertson…trying to take the Republican Party away from the Republican Party, and make a religious organization out of it. If that ever happens, kiss politics goodbye.”

He was still the model of indiscreet speech, still speaking his mind on the late Lyndon Johnson, “the most dishonest man we ever had in the Presidency,” he told Grove. In his autobiography he had called Johnson “the epitome of the unprincipled politician,” “a dirty fighter,” a man who would “slap you on the back today and stab you in the back tomorrow.” The only other politician he detested as heartily was Richard Nixon: “a twofisted, four-square liar,” he wrote.

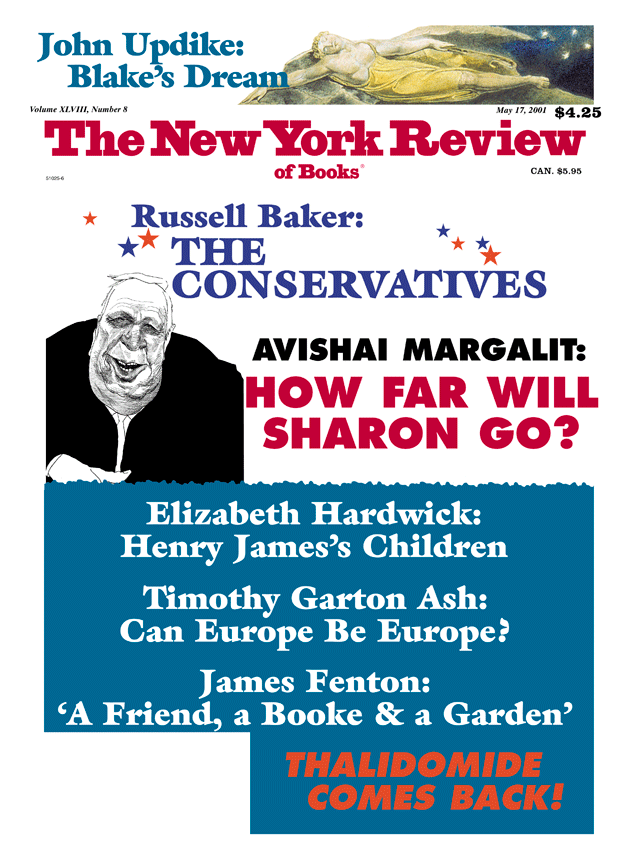

This Issue

May 17, 2001