History has a way of proving over and over the truth of the grim line in Lucretius (1.101):

Tantum religio potuit suadere malorum. (“How suasive is religion to our bane.”)

We are regularly told, with regard to the scandal of child abuse by priests, that pedophilia affects a minority of men in all walks of life, that the occurrence among priests is extraordinary neither in kind nor in frequency. But the intrusion of religion into the picture does affect its character and probably its rate. For one thing, pedophilia outside the priesthood leads to abuse of little girls as much as or more than of little boys. There have been few reported cases of girls as the object of priestly molestation, even though—as Michel Dorais points out in Don’t Tell—boys find it harder to report their abuse, since it involves cultural biases against homosexuality, beyond just the experience of coercion. Where (as in Australia) the Catholic religious orders ran separate orphanages for boys and girls, frequent molestation was reported only in the former institutions.

Priestly pedophilia is also set apart from other varieties by the fact that the seduction technique employs religion. Almost always some form of prayer has been used as foreplay. The very places where the molestation occurs are redolent of religion—the sacristy, the confessional, the rectory, Catholic schools and clubs with sacred pictures on the walls. One of the victims of Father Paul Shanley, of the Boston archdiocese, says that his ordeal began in the confessional, when he confessed the “sin” of masturbation. The priest told him that masturbation could be a “lesser evil” and that he would help him work out his problem. He did this by taking him to a cabin he kept in the woods, where the priest taught the boy how they could masturbate each other.1 This pattern occurs over and over—a conjunction of the overstrict sexual instruction of the Church (e.g., on the mortal sinfulness of masturbation, even one occurrence of which can, if not confessed, send one to hell) and a guide who can free one of inexplicably dark teaching by inexplicably sacred exceptions. The victim is disarmed by sophistication and the predator has a special arsenal of stun devices. He uses religion to sanction what he is up to, even calling sex part of his priestly ministry. One victim of Father Shanley says that he represented his sexual predation as an act of “healing.” According to a gay weekly, Shanley had made the same claim in a public speech.

In the archdiocese of Milwaukee, a thirteen-year-old was putting on his cassock in the sacristy before serving as an altar boy at a funeral Mass. The priest who was about to say the Mass, Richard Nichols, came over to him before going out to the altar and fussed with the cassock, saying he was making him look better. After the Mass, the priest came up behind him, plunged his hands (which had just consecrated the eucharistic host) down the front of his pants, and grabbed his penis, saying, “I can see funerals really excite you.” The boy broke away, but afterward the priest made it a point to come over and compliment him on his looks whenever he saw him.

For a long time the boy was ashamed to tell his parents of the incident, but when he did, his parents went to the chancery and complained about the priest. Archbishop Rembert Weakland wrote the boy asking him to forgive Father Nichols, and offered counseling with a therapist. The archdiocesan communications director urged the parents not to report the matter to the police. Father Nichols had by then become a practicing child psychologist, in addition to performing the priestly duties still being authorized by Archbishop Weakland. Nichols later admitted to having performed oral sex with one of his boy patients in 1978 (three years after his molestation of the altar boy in the sacristy). The priest retired to a condominium he owned with his mother.[2 ]

Another pattern is manifested here—the belief of the predators that they can counsel both victims and other predators. Father Shanley repeatedly suggested that he become a counselor to priests accused of molestation or that he run a “safe house” for them. Indeed, the instinct of the predators leads them by a kind of radar to children already disturbed in some way, to whom they could offer their sexual “ministrations” as a solution to their problems. Alberto Moravia’s novel The Conformist, about a man molested as a child, is remarkably insightful on the way the child is presented as “needing” because of his previous disturbance—but to whom the “healing” becomes a curse. Apologists for the priests have used this neediness in the child to exonerate the priest, saying that the child provoked him. A report of one of Father Shanley’s talks in the 1970s says: “He stated that the adult is not the seducer, the ‘kid’ is the seducer, and further the kid is not traumatized by the act per se, the kid is traumatized when the police and authorities ‘drag’ the kid in for questioning.”

Advertisement

It might be thought that churchly surroundings and sacred rites would discourage the priest’s sexual aggression. They seem rather to have stimulated them, providing a frisson of the forbidden. It was while celebrating an Easter meal with a family in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, that a priest, William Effinger, suggested that the son in the family serve his Mass the next day, and stay overnight at the rectory so he could rise early for that assignment. At the rectory, Father Effinger said that there was only one bed, so they would both have to sleep in it. No doubt there was a crucifix on the wall, as in most priests’ bedrooms. In Moravia’s The Conformist, the defrocked priest is kept from raping a young boy by the sight of a crucifix. (On a later occasion he does assault the boy, but only after removing the crucifix from the wall.)

Father Effinger was not inhibited by any sacredness of site or symbols from raping his victim—whose shamefaced agony was so obvious to his mother the next morning, when she went to see him serve Mass, that she quickly got the story from him and took it to Archbishop Weakland, who promised her that Father Effinger would be reassigned where he would not have access to children. He recommended for the boy a psychologist the archdiocese used, who reported back to the chancery, as part of his services to it, that the boy’s father “had the rare and God-given sense not to scream both to the police for justice and to heaven for vengeance”—so Father Effinger was reassigned to a parish by Weakland, where he was convicted of molesting another boy and sentenced to ten years in prison, where he died. When the boy finally brought suit for damages, a judge threw out the case because the statute of limitations had expired—and the archdiocese successfully countersued for the $4,000 it had spent on the court procedure.3

Some who are defensive about the Church’s terrible record try to throw doubt on the credibility of the victims’ stories (though many priests have admitted to the charges or have been convicted in trials). These defenders also point out that the accusations go back for decades—since admitting to what happened to them was especially painful for victims whose parents were unwilling to accept that priests could be so vile. Going back to the early careers of priests who have successfully hidden their crimes for years is an important aspect of these cases, since it involves the ethos of Catholicism from the mid-twentieth century, when the priest was an especially holy figure. This was borne in upon altar boys, who were forbidden (like all lay people) to touch the eucharist. When the altar boy poured water from a cruet into the chalice, it was over the joined fingers and thumbs of the priest—the so-called consecrating fingers which hold the eucharistic host when pronouncing the words that transform it into Christ’s body. To impress us with the importance of these fingers a nun told us of a Jesuit missionary in Canada who had his fingers chewed off by a “squaw” as part of his torture—so he could not say Mass until the pope gave him a dispensation to use other fingers. In the ordination rite, those fingers are tied in linen strips, setting them apart from profane use. It was the custom in the United States to give these strips to the mother of the ordained man, and she often was buried with them in her coffin.

The special tie of the priest to his mother was part of that infantilizing of the priesthood that has much to answer for in the current scandals—an infantilizing process that was encouraged by the old custom of beginning training for the priesthood as soon as boys could be induced to desire it, with the permission of the parents, which often meant with the encouragement of the mothers. Early applicants were set apart in “minor seminaries” (high school equivalents), where dating girls was blocked. It was a common saying that a woman never lost a son who became a priest. Pope John Paul II even used a mother’s special connection with the priesthood through her son to argue that there is no need to ordain women as priests, since their sons are their surrogates as priests.4

An eighty-year-old priest recently wrote to a friend of mine that he regrets having become a priest to satisfy his mother, a devout alcoholic, who thought she was redeeming her own life by offering him to God. When he tried to turn back before ordination, her tears deterred him. He realized too late that this was a strategy “the Church has for replenishing itself in its priesthood.” Donald Cozzens, former rector of a seminary and diocesan director of vocations, notes in The Changing Face of the Priesthood that “it is not uncommon for some mothers of priests to build their primary identity on their status as a ‘mother of a priest,'” which can reduce the son to a puer aeternus. I observed the special relationship of priest and mother in 1981. After writing some columns about our local cardinal’s financial dishonesty, I was surprised to find a package arrive at my office containing a priest’s chalice studded with precious gems. I called the chancery to see if a chalice had been stolen, and found it had. Apparently the thief or a fence wanted to return it, but not to the cardinal. The priest who came to pick it up told me that his widowed mother had put her engagement diamond, and all her other jewels, on the cup as her present when he was ordained.

Advertisement

Eugene Kennedy, an emeritus professor of psychology who has been a counselor to priests for years, reminds me that the sentimental climax of the movie Going My Way had the priest played by Bing Crosby fulfill the dearest hope of his dying pastor (Barry Fitzgerald) by bringing his mother to America from Ireland. Lest that be seen as just a fiction, we should remember that Cardinal Bernard Law wheeled his mother out in Rome when he was consecrated a cardinal and led his Boston delegation in singing the Irish song “A Mother’s Love Is a Blessing.”5

The current pope encourages this fixation on the mother by telling priests that they should think of their mothers as the Virgin Mary—they are “offered up” by their mothers, just as Jesus was offered up by Mary. This idealization of the mother-as-Mary may have something to do with the taboo some priests (not all, obviously) feel against touching women, making boys an apparently safe way of avoiding that taboo. Dorais argues that fear of dealing with women makes some pedophiles seek a substitute in the “feminine” aspects of boys—inducing more guilt in the boy, who suspects himself of being targeted because he is not a “real boy.” The matter is not helped by the way boys have been dressed in skirts (as altar boys or choir boys) to enter the sanctuary with the priest, the pair of them set off in their special insignia. The effeminate, in the eyes of the priest-pedophile, is not a female, so he is not breaking his vow of celibacy. The partner he chooses is doubly unmarriageable, since he is not only below the legal age for marriage but of the wrong gender as well. Such men have not betrayed their mothers by having relations with a rival woman. The promise was kept: she did not lose her son.

The infantilized priest is given prerogatives dangerous in the hands of the immature. His powers are emphasized and revered. Altar boys see the hands that were once bandaged wrapping large elaborate bandages all around the priest’s consecrated body before it approaches the altar—layer on layer of anachronistic clothing that cinctures, insulates, and turns the man into an object entirely set apart from daily use. Until the Second Vatican Council, even the language the boys were supposed to be sharing with the celebrants of Mass was a mystery to them. A nun taught me to make one of the Latin responses by thinking of “Etcom Spiri 2-2-0.” Only in high school would I learn that the words were divided this way: Et cum spiritu tuo. When priests took off their Mass vestments, they donned their clerical dress, with a special collar acting as a kind of barrier; and monsignori and bishops and cardinals became more flamboyantly sacred icons, in capes with red piping or large bishops’ rings.

In the early Sixties, I spent a day with John Wright, then the bishop of Pittsburgh, who loved to sweep around town in his chauffeured limousine, greeting people with his ring thrust forward for the kissing. At one point he directed his limousine to a Church-run home for deserted pregnant women, an admirable institution. Before we went inside, he had the chauffeur open the car trunk, which was entirely filled with large boxes containing Barbie-like dolls. (They may have been Barbies, in fact; I could not have told, since I was not then familiar with the product.) He told me a Catholic businessman had given him the dolls to hand out as presents, so he had the chauffeur load his arms with these toy-adult figures to bestow on the expecting mothers. His satisfaction in playing Lord Bounteous made it impossible for him to recognize the ludicrous inappropriateness of the gifts. They were infantilizing tokens, delivered by one who was himself infantilized.

Back in his mansion, the bishop took me to a large locked room that contained his favorite treasures—books, manuscripts, relics, memorials, paintings, and statues, all of them celebrating Saint Joan of Arc. He boasted that he had every movie made about his heroine, beginning with silent treatments. He had projection equipment to show them all, and said that he had not only been an expert adviser for the 1948 film Joan of Arc, but got to know its star, Ingrid Bergman. Some Catholics censured Ms. Bergman after she publicly deserted her husband a year after Joan of Arc’s release; but her contribution to his self-importance made Wright forgive her. I left the mansion certain that I had been in the presence of a large fat baby who would never grow up. Later, as a cardinal appointed to the Curia in Rome, he would prove that he could be more pompous than any Italian prelate. (I was surprised not long ago, when studying the John Singer Sargent murals on the top floor of the Boston Public Library, to see that a whole room there now contains the Wright collection of Joaniana.)

The combination of arrested boyhood and numinous supernatural power makes for some very strange personalities, recalling Aristotle’s dictum that a man outside normal social relations is either subhuman or superhuman, “clod or god.”6 The priest is not just a mentor, like a scoutmaster, not just a buddy, like a coach. He has the power to forgive sins—which involves the prior ability to define, assess, and assign responsibility for the sin. He is not like other men, and everything is done to keep him aware of that fact. Father Donald Cozzens says that this puts a priest in the precarious position where he may belittle or betray his baptismal identity (as a fellow Christian with all Christians) in the name of his special (“higher”) calling:

Operating just below the surface of consciousness, a complex of psychic forces encourages behaviors and attitudes which subvert his conscious desire to serve the people of God. Included among these attitudes and behaviors are clericalism, elitism, careerism, legalism, envy, and competition. When gripped by these psychic forces it is easy for the priest to over-identify with his priestly persona and thereby lose touch with his baptismal identity. The need to buffer his exalted priestly identity may well abort his potential for honest relationships with men and women. His priestly persona becomes his rock of identity and the wellspring of his solace. The subtle balance between his baptismal and priestly identities is lost. The line is crossed and he treasures the bitter-sweet belief that he is not like other men [emphasis in the original].

The American priests’ superiors did not rebuke their tendency to hold themselves above others. They encouraged it. Their bishops had not only imitated Italian princes, but Italian princes of the Renaissance. As Eugene Kennedy writes in The Unhealed Wound, a predecessor of Cardinal Law in Boston, Cardinal William O’Connell, set the tone for ecclesiastical style in the twentieth century when he returned from Rome “with an entourage that included a coachman, a valet, and a music master”:

Not only had he built a large, antique-filled residence in Boston, but he further signaled his identification with a Brahmin class by maintaining a winter home in the Bahamas and a summer one at Marblehead. So often did he travel to the former that his priests referred to him as “Gangplank Bill.” On the edge of the Cape, he strode the beach in his flat black hat and frock coat, his episcopal chain glinting in the sun, his gleaming limousine trolling the sands behind him.

Cardinal Mundelein of Chicago was equally special:

He transported treasures from the Continent and re-created Roman sites and scenes, such as the Barberini bees he set swarming on the library ceiling of his country-estate seminary forty miles north of his many-chimnied mansion on the city’s North Side. On the seminary grounds, he slept in a brick-trimmed replica of Mount Vernon and was driven back and forth to Chicago in a limousine with crimson-strutted wheels.

This grandeur proved to bishops’ mothers that they were indeed God’s chosen. Yet Catholics were not the only ones who inflated priestly egos. Non-Catholics could be even more deferential. That showed in little things like the way people who slipped into the occasional “Damn” or “Hell” in a priest’s presence would murmur, “Pardon me, father.” It showed in special privileges assumed or asserted. A man recently told me how a priest drove him to the airport to pick up a friend. The priest drove to the entryway, clearly marked “No Parking,” and got out of the car to meet the plane. When his passenger asked if he wasn’t afraid of getting a ticket, the priest pointed to his “Catholic Clergy” sign in the windshield and said “They’ll never ticket that car.” They didn’t.

A man without a wife to puncture his pomposity, without children to challenge his authority, in relations carefully structured to make him continuously eminent, easily becomes convinced of his superior wisdom. Since many priests have been only sketchily educated outside their formal subjects, they feel that the source of their wisdom must be their supernatural powers, not their intellectual development. It is generally easy for religion to move from the numinous to the antinomian, to the idea that believers are above the rules that bind others. This is where religion and sex slide easily into each other, and there is much in Catholic iconography that can encourage a sexual religiosity, from the mystic writings of ecstatic union to the statues of the naked and suffering Saint Sebastian, the “classic pincushion of homoerotic art.”7 (Waugh chose very well the name of his narrator’s homosexual friend in Brideshead Revisited.) The art–religion nexus is as true of heterosexual as of homosexual imagery. Bernini’s orgasmic Saint Teresa in Rome’s Santa Maria della Vittoria is well known, but even more explicitly sexual is his Blessed Lodovica Albertoni in the same city’s San Francesco a Ripa. And there are more lurid images still—I think of Francesco Vanni’s painting of Saint Catherine licking the bloody wound in Christ’s side (this is in the Convent of San Girolamo in Siena).

The “innocent” sexuality of antinomian sects is made even easier for a man who is so clearly marked off from others, for whom he prescribes the rules for absolution of their sins. This makes more explicable the fact that the priest-pedophile, even one who admits what he has done, shows so little awareness that it was wrong. Perhaps, for others, it is wrong. Not for him. Not for the antinomian. Father Cozzens, who has investigated and counseled pedophile priests, writes:

I sensed little guilt for their seductions. The only regret I could identify was associated with their being caught. For the most part, the men I worked with were more concerned about themselves and their futures than for their victims. From my relatively brief work with them I came to see them as focused sociopaths—little or no moral sense, no feelings of guilt and remorse for what they had done, at least in this area of their lives. When it came to their misconduct with minors there was minimal evidence of conscience. I remember having to ask, “Are you sorry for the harm you did, for the suffering of the victim?” They answered, not surprisingly, “Yes”—but with little conviction. I don’t remember one priest acknowledging any kind of moral torment for the behavior that got him in trouble [emphasis added].

This conviction that they are above the law has much to do with the compliance of their victims. Not only is the priest a guardian of mysteries, respected by the victims’ families and other authority figures, taking the victim into special places marked off from the “profane” and explicable. His own conviction adds to his weight of authority. If he is so sure that it is all right, who is the youngster to challenge his credentials?

In his sensitive analysis of the cases of thirty victims of (nonclerical) pedophilia, Michel Dorais notes that most cases of sexual assault in his study are by fathers or father figures (stepfathers, uncles, older brothers, or cousins). They account for twenty-two of the thirty cases. The victim is not only temptingly available, but dependent on the father figure for support, used to obeying in other areas of life, conditioned to respect the elder’s demands. A priest is a father-figure plus. The child is available to him, or made available, in surroundings where his authority is sanctioned by all the accumulated culture of Catholicism. He and the boy are joint partakers of the mysteries at the altar and in the confessional. The child has been taught to confess to the priest intimate matters he would never reveal to his own father. His mother lends her support to the priest’s authority. Until recently, unwillingness to believe allegations against priests imposed a silence on the victims. One of the abused boys in Boston was struck in the face by his mother when he told her a priest had molested him. What is unthinkable to mothers becomes unsayable to victims.

The observations made in the preceding paragraphs receive a chilling confirmation in the personnel file, kept by the diocese, of the Boston pedophile Paul Shanley, a file released by the lawyers for his victims. The man expresses no feelings of guilt in these documents, and his superiors never suggest that he should. In fact, though he admitted in treatment to sexual acts with minors, he continues to feel that he is the wronged person. A victim trying to have him removed from contact with children is a “stalker”—a judgment Boston’s Cardinal Law seemed to support when he wrote him a letter expressing sympathy: “It must be very discouraging to have someone following you.” Shanley defied archdiocesan efforts to make him give up living with a young male roommate (“Do you prefer that I have a female roommate?”). Allowed to go to California with full priestly credentials (he pleaded that poor health made him seek a “support group” there), Shanley duns the archdiocese for more funds, saying he is forced to make beds or act as a security guard in a hotel in order to earn money for his medicine. He does not say that he and a fellow priest are co-owners of the hotel, a gay resort.

In the file, Cardinal Law and several of his administrative bishops express unfailing support and sympathy for Shanley, and no sympathy—indeed little curiosity—about the minors he had sex with. One reason may lie in this communication by Shanley to an archdiocesan administrator: “I have abided by my promise not to mention to anyone the fact that I too had been sexually abused as a teenager, and later as a seminarian by a priest, a faculty member, a pastor and ironically by the predecessor of one of the two Cardinals who now debates my fate.” His superiors worried little about what he did. Was that because they were more concerned with what he knew?

—This is the first of two articles on pedophilia in the Church.

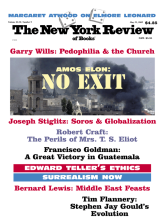

This Issue

May 23, 2002

-

1

From the Shanley documents released by the law firm of Greenberg, Traurig, Boston. ↩

-

3

Tom Kertscher and Marie Rohde, “Archdiocese Fought Hard in Court,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 15, 2002. ↩

-

4

Che cosa ha detto il Papa sulle donne (Rome: Paoline Editoriale, 1996), p. 60. ↩

-

5

Jack Thomas, “Scandal Darkens a Bright Career,” The Boston Globe, April 14, 2002. ↩

-

6

It is hard to translate the alliterative jingle of Aristotle’s saying (Politics 1253a29) that outside the polis one is either degraded or divine, therion or theos, where therion means a (subhuman) animal. ↩

-

7

Ellis Hanson, Decadence and Catholicism (Harvard University Press, 1997), p. 338. Discussing the appeal of Catholic ritual and images to gay men, Hanson concludes (p. 372): “I would have to admit that the turbines of Christianity have traditionally spun with an extraordinary quantity of queer steam.” See also Mark Jordan’s comments on his fellow “Liturgy Queens” in The Silence of Sodom (University of Chicago Press, 2000), pp. 187–194. ↩