1.

In her memoir about Bruce Chatwin, Susannah Clapp tells the following story. Not long before his death, already very ill, Chatwin was receiving guests in his room at the Ritz in London. Many of them left with a gift. One friend was given a small jagged object which Chatwin identified as a subincision knife, used to slit the urethra in an Aboriginal initiation rite. He had found it in the Australian bush, he said, with his connoisseur’s eye: “It’s obviously made from some sort of desert opal. It’s a wonderful color, almost the color of chartreuse.” Not long after, the director of the Australian National Gallery spotted the object in the grateful recipient’s house. He held it up to the light and muttered: “Hmmm. Amazing what the Abos can do with a bit of an old beer bottle.”1

Chatwin had the gift of polishing reality like Aladdin’s lamp to produce stories of deep and alluring mystery. He was a myth-maker, a fabulist who could turn the most banal facts into poetry. To question the veracity of his stories is to miss the point. He was neither a reporter nor a scholar, but a raconteur of the highest order. The beauty of this type of writing lies in the perfect metaphor that appears to illuminate what lies under the factual surface. Another master of the genre was Ryszard Kapuściński, the Polish literary chronicler of third-world tyrannies and coups. One entire book of his, The Emperor, a poetic rendering of life in the court of Haile Selassie, is often read as a metaphor for Poland under communism—an interpretation always denied by the author himself.

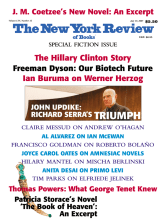

The German film director Werner Herzog was a friend of Chatwin’s as well as Kapuściński. He made a film—by no means his best—of one of Chatwin’s books, entitled Cobra Verde,2 about a half-crazed Brazilian slave-trader in West Africa, played by a half-crazed Klaus Kinski. The match was a natural one, for Herzog, too, shares the gift of the great fabulators. In his many interviews—remarkably many for a man who says he would prefer to work anonymously, like a medieval artisan—Herzog often compares himself to the Moroccan spellbinders who tell stories in the marketplace of Marrakech. As was true of Chatwin and Kapuściński, Herzog feels a great affinity with what a friend of mine, much at home in Africa himself and quite critical of Kapuściński, has called “tropical baroque”—remote desert countries or dense Amazonian jungles.3 Like them, Herzog—modestly of course, as if it’s really of no great consequence—likes to tell tales of his own frightful hardships and narrowly missed catastrophes: filthy African jails, deadly floods in Peru, rampaging bulls in Mexico. In a filmed BBC interview shot in Los Angeles, Herzog, in his deep, mesmerizing voice, is just explaining how in Germany nobody appreciates his films anymore, when you hear a loud crack. Herzog doubles over. He’s been shot by an air rifle just above his floral underpants, leaving a nasty wound. “It’s of no significance,” he says in his deadpan Bavarian drone. “It doesn’t surprise me to get shot at.”4 This is such a Herzogian moment that you would almost suspect that he directed the whole thing himself.

The suspicion is not entirely frivolous, for Herzog not only expresses no interest in literal truth; he despises it. Cinéma vérité, the art of catching truth on the run with an often hand-held camera, he dismisses as “the accountant’s truth.” While Ryszard Kapuscinski always maintained that he was a reporter, and denied making things up for poetic or metaphorical effect, Herzog is quite open about inventing scenes in his documentary films, for which he is justly famous. In fact, he doesn’t recognize a distinction between his documentaries and his fiction films. As he told Paul Cronin in the excellent book Herzog on Herzog5: “Even though they are usually labeled as such, I would say that it is misleading to call films like Bells from the Deep and Death for Five Voices ‘documentaries.’ They merely come under the guise of documentaries.” And Fitzcarraldo, a fiction film about a late-nineteenth-century rubber baron (played by Klaus Kinski) who dreams of building an opera house in the Peruvian jungle and has a ship pulled across a mountain, has been described by Herzog as his most successful documentary.

The opposite of “accountant’s truth” for Herzog is “ecstatic truth.” In a recent appearance at the New York Public Library he explained: “I’m after something that is more like an ecstasy of truth, something where we step beyond ourselves, something that happens in religion sometimes, like medieval mystics.”6 He achieves this to wonderful effect in Bells from the Deep, a film about faith and superstition in Russia—Jesus figures in Siberia and the like, another fascination he shared with Chatwin. The movie opens with an extraordinary, hallucinatory image of people crawling on the surface of a frozen lake, peering through the ice, as though in prayer to some unseen god. In fact, as Herzog narrates, they are looking for a great lost city called Kitezh that lies buried under the ice of this bottomless lake. The city had been sacked long ago by Tartar invaders, but God sent an archangel to redeem the inhabitants by letting them live on in deep underwater bliss, chanting hymns and tolling bells.

Advertisement

The legend exists and the image is hauntingly beautiful. It is also entirely fake. Herzog rounded up a few drunks at a local village bar and paid them to lie on the ice. As he tells the story: “One of them has his face right on the ice and looks like he is in very deep meditation. The accountant’s truth: he was completely drunk and fell asleep, and we had to wake him at the end of the take.” Was it cheating? No, says Herzog, because “only through invention and fabrication and staging can you reach a more intense level of truth that cannot otherwise be found.”

This is exactly what admirers of Chatwin say. And I must confess to being one of them. But not without some feeling of ambivalence. The power of the image is surely enhanced by the belief that these are real pilgrims and not drunks who are paid to impersonate pilgrims. If a film, or book, is presented as being factually accurate, there has to be a certain degree of trust in veracity which is not quite the same as the suspension of disbelief. Once you know the real unembellished story, some of the magic is lost, at least to me. And yet the genius of Herzog as a cinematic spellbinder is such that his documentaries work even as fiction. In defense of his peculiar style, it might be said that he uses invention not to falsify truth, but to sharpen it, enhance it, make it more vivid. One of his favorite tricks is to invent dreams for his characters, or visions they never had, which nonetheless ring true, because they are in keeping with the characters. His subjects are always people with whom he feels a personal affinity. In a way the main characters in his films, feature and documentary, are all variations of Herzog himself.

Born in Munich during the war, Herzog grew up in a remote village in the Bavarian Alps, without access to telephones or movies. As a child he dreamed of becoming a ski jumper. Defying gravity, trying to fly, on skis, in balloons, in jet planes, is a recurring theme in his films. He loves Fred Astaire for that reason, airborne in his dancing shoes. And he made a documentary in 1974, entitled The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner, about an Austrian ski jumper. Steiner is a typical Herzogian character, a monomaniacal loner, pushing himself to the limits, mastering the fear of death and isolation. Steiner is, in Herzog’s words, “a close brother of Fitzcarraldo, a man who also defies the laws of gravity by pulling a ship over a mountain.”

In 1971, Herzog made one of his most astonishing documentaries about another form of solitude, the most extreme form, of people trapped in the isolation of their blindness and deafness. The main character in Land of Silence and Darkness is a middle-aged German woman of tremendous courage, named Fini Straubinger, who can communicate only by tapping a kind of braille on another person’s hand. Since she went blind after an accident in her teens, she still had visual memories, the most vivid of which, she recalls, was the look of ecstasy on the faces of ski jumpers as they soared through the sky. In fact, Fini Straubinger had never seen a ski jumper. Herzog wrote those lines for her, because he thought this “was a great image to represent Fini’s own inner state and solitude.”

Does this diminish the film, or distort the truth about Fini Straubinger, even though she agreed to speak those lines? It is hard to give an unequivocal answer. Yes, it is a distortion, because it is invented. But it does not diminish the film, because Herzog manages to make it look plausible. We can never really know the inner life of Fini Straubinger, or anyone else’s, for that matter. What Herzog does is imagine her inner life. The ski jumper story is part of how he sees Fini Straubinger. It illuminates her character for him. That is another kind of truth, the portraitist’s truth.

Advertisement

Herzog likes to think of himself as an artistic outsider, out on a dangerous edge, flying alone, as it were. In many ways, however, he is mining a rich tradition. The yearning for ecstasy, man alone in wild nature, deeper truths, medieval mystics, all this smacks of nineteenth-century Romanticism. Herzog’s frequent use of Richard Wagner’s music (in Lessons of Darkness, for example, his film about the burning oil wells of Kuwait after the first Gulf war), as well as his often professed love of Hölderlin’s poetry, suggests that he is quite aware of this affinity. His loathing of “technological civilization,” and his idealization of nomadism and ways of life as yet untouched by our blighted civilization, are of a piece with this. He can be quite moralistic, even puritanical. “Tourism is sin,” he announced in his so-called Minnesota Declaration of 1999, and “walking is a virtue.”7 The twentieth century, with its “consumer culture,” was a “massive, colossal and cataclysmic mistake.” Meditating Tibetan monks, he claimed at his Goethe Institute talk, are good, but meditating Californian housewives “an abomination.” Why? He didn’t say. One imagines it is because he considered the housewives inauthentic, not true believers, only in it for the lifestyle.

As with many Romantic artists, landscape is an important element in Herzog’s work, and part of his striving for a kind of visionary authenticity. Few directors match his skill in depicting the fertile horror of the jungle, the terrifying bleakness of deserts, or the awful majesty of high mountains. He never uses landscapes as backdrops. Landscape has character. About the jungle he has remarked that it “is really about our dreams, our deepest emotions, our nightmares. It is not a location, but a state of our mind. It has almost human qualities. It is a vital part of the characters’ inner landscapes.” Caspar David Friedrich, an artist Herzog admires, never painted the jungle, but this description could easily be applied to his pictures of lone figures gazing at the stormy Baltic Sea or standing above the clouds on snowy peaks. Friedrich saw landscape as a manifestation of God. Herzog, who went through a “dramatic religious phase” and converted to Catholicism as a teenager, sees “something of a religious echo in some of my work.”

Postwar Germans, for obvious reasons, sometimes feel uneasy with this kind of Romantic straining for the sacred. It smacks too much of the Third Reich, with its exultation of a bogus Germanic spirit. Perhaps this explains why Herzog’s films have found an easier reception abroad (he now lives in Los Angeles, a city he loves for its “collective dreams”). In fact, Herzog himself is extremely sensitive to the barbarism unleashed in his country. He says: “I am even apprehensive about insecticide commercials, and know there is only one step from insecticide to genocide.” Herzog certainly never toys with Nazi aesthetics. What he has done is more interesting: he has reinvented a tradition that was exploited and vulgarized by the Nazis. The kind of mountain films, for instance, that Leni Riefenstahl acted in and directed, full of ecstasy and death, fell out of favor after the war because, as Herzog says, they “fell in step with Nazi ideology.” So Herzog set out to create “a new, contemporary form of mountain film.”

To me, watching Herzog’s films brings to mind a different, more popular kind of romance that long preceded Hitler: the novels of Karl May about intrepid German trappers in the American Wild West.8 May’s most popular hero was Old Shatterhand, who roamed the prairies with his “blood brother,” an Apache brave named Winnetou, the typical nineteenth-century Noble Savage. Apart from his trusted rifle, Old Shatterhand had no truck with our technological civilization. He used all his ingenuity to survive in the dangerous state of nature. Since Karl May had never even visited America when he wrote his western novels in the 1890s, his descriptions were entirely invented, and at the same time infused with realistic details culled from maps, travel accounts, and anthropological studies.

2.

Of all Herzog’s heroes, fictional or not, the closest to Old Shatterhand is not, as one might think, one of the obsessed visionaries played by Klaus Kinski: Aguirre, the Spaniard in search of El Dorado, or Fitzcarraldo. Nor is it Timothy Treadwell, the bear-hugging American in Grizzly Man (2005), who thought that he could survive in the icy wilds of Alaska because the grizzly bears would reciprocate his love instead of devouring him, as they end up doing. Old Shatterhand would not have been so sentimental about nature. He understood its perils.

No, a much more typical Karl May figure was a fighter pilot named Dieter Dengler. Born in the German Black Forest, Dengler became an American citizen, because ever since he saw a US fighter plane streak past his house at the end of World War II, he wanted to fly. Since he couldn’t fulfill his ambition just then in Germany, he became an apprentice clockmaker before boarding a ship bound for New York with thirty cents in his pocket. He joined the US Air Force and spent several years peeling potatoes before realizing that he needed a college degree, which he completed while living in a VW bus in California. No sooner was he taken into the Navy and trained to become a fighter pilot than he was shipped off to serve in the Vietnam War. He was shot down on a secret mission over Laos. Captured by the Pathet Lao, he was marched through the jungle and frequently tortured. It would amuse his captors to suspend their prisoner upside down with his face buried in an ants’ nest, or drag him behind an ox, or drive bits of bamboo into his skin.

Locked up in a prison camp with other prisoners, Americans and Thais, he supplemented his diet of maggoty rice gruel with rats and snakes fished out of the latrine and eaten raw. Making good use of his technical ingenuity, as well as his almost superhuman survival skills, Dengler escaped with his buddy, Duane Martin. They hacked their way barefoot through the monsoon-soaked jungle toward the Mekong River, bordering Thailand. After they ran into hostile villagers, Duane’s head was cut off with a machete. Not long after that, through sheer luck, Dengler, by then a skeletal figure, was spotted by a US pilot and rescued. “This was the fun part of my life,” he would say to people who wanted to know how he could possibly have endured so much hardship.

Herzog feels drawn to strongmen, but is quick to add that this does not mean bodybuilders. For him bodybuilders are frivolous, inauthentic, like those meditating Californian housewives, “an abomination.” Herzog’s very first film, entitled Herakles, made in 1962, when he was twenty years old, splices together images of car crashes, bombing raids, and bodybuilders in a way that shows disapproval of gratuitous machismo. A Herzogian strongman can be a strongwoman too, like Fini Straubinger, or Juliane Köpcke, the lone survivor of an air disaster in Chile, whose story Herzog recounts in Wings of Hope (1999). The Herzogian strongperson is not just physically, but mentally tough, someone who knows how to beat the odds.

If Dieter Dengler hadn’t existed, Herzog would have made him up. He is the perfect Herzogian strongman, and the subject of one of Herzog’s best documentary films, Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997), made for a German television series about journeys to hell. The very first shot is already an invention. We see Dieter enter a tattoo parlor in San Francisco, ostensibly to have an image of death driven by wild horses tattooed onto his back. But he decides against it. He could never have a tattoo like that, he says, for when he was close to dying and “the doors of heaven opened,” he didn’t see wild horses but angels: “Death didn’t want me.”

Dieter, in fact, never thought of having a tattoo at all. Herzog created the scene to make a point about Dieter’s narrow escape. The next scene shows Dieter arriving in his convertible at his house north of San Francisco. The landscape is strangely reminiscent of the pre-war German mountain movies: misty, high up, seemingly remote from human civilization. Dieter opens and closes the car door several times, a little obsessively, then does the same with his front door, which is unlocked. Some people, he says, might find this habit a little peculiar, but it has to do with his time in captivity. Opening doors gives him a sense of freedom.

In real life, Dieter was no more in the habit of fetishizing open doors than he was of getting tattooed, even though he did have a set of paintings on his wall showing open doors. He was acting himself in scenes contrived by Herzog. Later on in the movie, we hear about Dieter’s recurring dream in the prison camp of the US Navy coming to rescue him, only to pass right by him while he frantically waves at the ships. An invention. And yet by the end of Little Dieter Needs to Fly we are left with an extraordinarily intimate portrait of a transplanted German hero like Old Shatterhand, who outshines his new American compatriots in such “typical German” virtues as efficiency, discipline, and technical competence. Dieter is himself a marvelous narrator, whose German-inflected voice blends interestingly with Herzog’s to the point of becoming almost indistinguishable. This is more than a simple case of the director’s identification with his subject; he almost becomes Dieter.

One of Herzog’s many talents as a filmmaker is his startling use of music. Matching up burning oil wells in Kuwait with Wagner’s Twilight of the Gods is perhaps too obvious, but seeing jet fighters take off from a US aircraft carrier to the sound of Carlos Gardel’s tango music is utterly effective. A Mongolian throat singer is used to accompany footage of a bombing raid on villages in Vietnam, producing images that are both horrifying and beautiful. Wagner is used again in a scene where Dieter explains the experience of near death. He is posed in front of a huge aquarium filled with blue jellyfish floating grotesquely like rubbery parachutes. This is what death looks like, says Dieter, as we hear the Liebestod on the soundtrack. Again, the image of the jellyfish was Herzog’s idea, not Dieter’s, but it is undeniably powerful.

The fact that Herzog, when asked, is quite open about his inventions does not entirely dispel one’s doubts about this kind of filmmaking. For if so much is invented, how do we know in the end what is true? Perhaps Dieter Dengler was never shot down over Laos. Perhaps he never even existed. Perhaps, perhaps. All I can say, as an admirer of Herzog’s films, is that I believe he is true to his subjects. None of the inventions—the doors, the jellyfish, the dreams—change Dieter’s account of what happened. They are metaphors, not facts. And Dieter himself saw the point of them.

The best example of this comes at the very end of the film, after we have seen Dieter return with Herzog and his crew to the Southeast Asian jungle, where he walks again barefoot through the bush, and is again tied up by villagers (hired by Herzog), and recalls in precise detail how he escaped and his friend Duane got killed. We have also seen him in his native village in the Black Forest, telling us about his grandfather, the only man in the village who refused to go along with the Nazis. And we have seen him back in the US, sharing a gigantic Thanksgiving turkey with Gene Dietrick, the pilot who rescued him from imminent death. After all that, in the last shot, before the epilogue about Dieter’s funeral at Arlington Cemetery—he died of Lou Gehrig’s disease—we see him walking around in wonder through the vast resting place for military aircraft in Tucson, Arizona. As the camera pans across row upon row of discarded jet fighters, helicopters, and bombers, Dieter declares that he has arrived in pilot’s heaven.

Herzog set this scene up too. Dieter had no intention of going to Tucson, Arizona. But his wonder looks genuine. Flying had been his lifelong obsession. He did need to fly, and it doesn’t matter who arranged for him to be in the Airplane Graveyard, for Little Dieter really does look as if he is in heaven.

Given the brilliant achievement of this documentary film, the notion of remaking the story as a feature film might strike one as eccentric. Dieter liked the idea, if only because he hoped to make a great deal of money out of it. (Unfortunately he died before the film was completed.) Herzog evidently was so taken with the man and his story that he couldn’t let it go. So he managed to amass something like a minor Hollywood budget for Rescue Dawn, and set off to Thailand with his crew and cast, including two well-known young actors, Christian Bale (Dieter) and Steve Zahn (Duane). The production was beset by the usual Herzogian difficulties: bitter rows, furious producers, uncomprehending crews, trouble with local officials.9 And uncommon hardships for some of the actors: Christian Bale lost so much weight for the part that he looked as if he really did emerge from an ordeal in the jungle. He is also, for the sake of authenticity, compelled to eat horrible-looking insects and snakes.

The actors are very good, especially in the minor parts. Jeremy Davis as Gene, one of the American prisoners who resists Dieter’s plans to escape, is especially fine. And Herzog’s eye for the beautiful terror of nature does not fail him. Yet much of what made Little Dieter Needs to Fly a masterpiece is missing. First of all Dengler himself. Somehow his story, reenacted in the feature film, fails to catch fire in the way it does in the documentary. It looks oddly conventional, even flat. And Dieter is much more American than in fact he was, although he still is tougher and more resourceful than anyone else in the movie. The ending, apparently close to the facts, showing Dengler being received back on his Navy ship by his cheering buddies, is pure Hollywood schmaltz compared to the mesmerizing images in the Tucson Airplane Graveyard.

The difference, I think, has everything to do with Herzog’s use of fantasy. In the documentary, his method is actually closer to that of a fiction writer than in the feature film. Rescue Dawn sticks to the facts of Dengler’s story, without adding much background, let alone any hint of an inner life. It looks like a well-made docudrama. In the documentary, however, it is precisely the collage of family history, dream images, personal eccentricities, and factual information that brings Dieter Dengler alive as a fully rounded figure. This doesn’t mean that the same effect cannot be achieved in a feature film. But it does show how far Werner Herzog has taken a genre that is commonly known as documentary film but that he calls “just films.” For want of a better word, that will have to do.

This Issue

July 19, 2007

-

1

With Chatwin: Portrait of a Writer (London: Jonathan Cape, 1997). ↩

-

2

The original novel was called The Viceroy of Ouidah. ↩

-

3

John Ryle, academic, Africanist, writer. ↩

-

4

The scene can be viewed on YouTube. The shooter fled and Herzog told the BBC producers to let him go. ↩

-

5

Faber and Faber, 2002. ↩

-

6

Werner Herzog in conversation with Paul Holdengräber, “Was the Twentieth Century a Mistake?,” New York Public Library, February 16, 2007. ↩

-

7

Traveling on foot was also one of Chatwin’s enthusiasms. He bequeathed his custom-made leather rucksack to Herzog. ↩

-

8

Hitler was a keen reader of May, but so was Albert Einstein. ↩

-

9

For a lively description of all this, see Daniel Zalewski’s report in The New Yorker, May 13, 2006. ↩