One of Germany’s most singular achievements is to have associated itself so intimately in the world’s imagination with the darkest evils of the two worst political systems of the most murderous century in human history. The words “Nazi,” “SS,” and “Auschwitz” are already global synonyms for the deepest inhumanity of fascism. Now the word “Stasi” is becoming a default global synonym for the secret police terrors of communism. The worldwide success of Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s deservedly Oscar- winning film The Lives of Others will strengthen that second link, building as it does on the preprogramming of our imaginations by the first. Nazi, Stasi: Germany’s festering half-rhyme.

It was not always thus. When I went to live in Berlin in the late 1970s, I was fascinated by the puzzle of how Nazi evil had engulfed this homeland of high culture. I set out to discover why the people of Weimar Berlin behaved as they did after Adolf Hitler came to power. One question above all obsessed me: What quality was it, what human strain, that made one person a dissident or resistance fighter and another a collaborator in state-organized crime, one a Claus von Stauffenberg, sacrificing his life in the attempt to assassinate Hitler, another an Albert Speer?

I soon discovered that the men and women living behind the Berlin Wall, in East Germany, were facing similar dilemmas in another German dictatorship, albeit with less physically murderous consequences. I could study that human conundrum not in dusty archives but in the history of the present. So I went to live in East Berlin and ended up writing a book about the Germans under the communist leader Erich Honecker, rather than under Adolf Hitler.1 As I traveled around the other Germany, I was again and again confronted with the fear of the Stasi. Walking back to the apartment of an actor who had just taken the lead role in a production of Goethe’s Faust, a friend whispered to me, “Watch out, Faust is working for the Stasi.” After my very critical account of communist East Germany appeared in West Germany, a British diplomat was summoned to receive an official protest from the East German foreign ministry (one of the nicest book reviews a political writer could ever hope for) and I was banned from reentering the country.

Yet this view of East Germany as another evil German dictatorship was by no means generally accepted in the West at that time. Even to suggest a Nazi–Stasi comparison was regarded in many parts of the Western left as outmoded, reactionary cold war hysteria, harmful to the spirit of détente. The Guardian journalist Jonathan Steele concluded in 1977 that the German Democratic Republic was “a presentable model of the kind of authoritarian welfare states which Eastern European nations have now become.” Even self-styled “realist” conservatives talked about communist East Germany in tones very different from those they adopt today. Back then, the word “Stasi” barely crossed their lips.

Two developments ended this chronic myopia. In 1989 the people of East Germany themselves finally rose up and denounced the Stasi as the epitome of their previous repression. That they often repressed at the same time—in the crypto-Freudian sense of the word “repression”—the memory of their own everyday compromises and personal responsibility for the stability of the communist regime was but the other side of the same coin. After 1990, the total takeover of the former East Germany by the Federal Republic meant that, unlike in all other post-communist states, there was no continuity from old to new security services and no hesitation about exposing the evils of the previous secret police state. Quite the reverse.

In the land of Martin Luther and Leopold von Ranke, driven by a distinctly Protestant passion to confront past sins, the forcefully stated wish of a few East German dissidents to expose the crimes of the regime, and the desire of many West Germans (especially those from the class of ’68) not to repeat the mistakes made in covering up and forgetting the evils of Nazism after 1949, we saw an unprecedentedly swift, far-reaching, and systematic opening of the more than 110 miles of Stasi files. The second time around, forty years on, Germany was bent on getting its Vergangenheitsbewältigung, its past-beating, just right. Of course Russia’s KGB, the big brother of East Germany’s big brother, did nothing of the kind.

After some hesitation, I decided to go back and see if I had a Stasi file. I did. I read it and was deeply stirred by its minute-by-minute record of my past life: 325 pages of poisoned madeleine. Helped by the apparatus of historical enlightenment that Germany had erected, I was able to study in incomparable detail the apparatus of political intimidation that had produced this file. Then, working like a detective, I tracked down the acquaintances who had informed on me and the Stasi officers involved in my case. All but one agreed to talk. They told me their life stories, and explained how they had come to do what they had done. In every case, the story was understandable, all too understandable; human, all too human. I wrote a book about the whole experience, calling it The File.

Advertisement

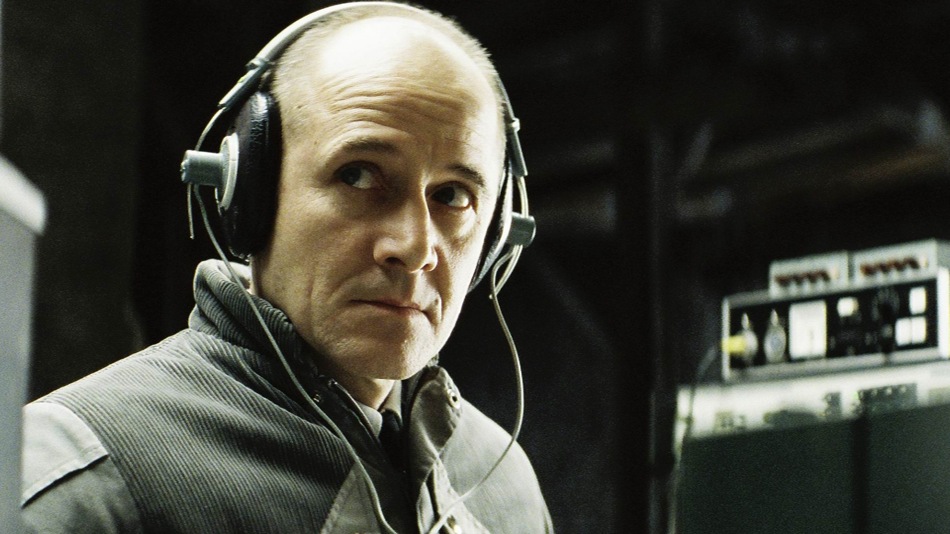

It was therefore with particular interest that I recently sat down to watch The Lives of Others, this already celebrated film about the Stasi, made by a West German director who was just sixteen when the Berlin Wall came down. Set in the Orwellian year of 1984, it shows a dedicated Stasi captain, Gerd Wiesler, conducting a full-scale surveillance operation on a playwright in good standing with the regime, Georg Dreyman, and his beautiful, highly strung actress girlfriend, Christa-Maria Sieland. As the case progresses, we see the Stasi captain becoming disillusioned with his task. He realizes that the whole operation has been set up simply to allow the culture minister, who is exploiting his position to extract sexual favors from the lovely Christa, to get his playwright rival out of his way. “Was it for this we joined up?” Wiesler asks his cynical superior, Colonel Anton Grubitz.

At the same time, he becomes curiously enchanted with what he hears through his headphones, connected to the bugs concealed behind the wallpaper of the playwright’s apartment: that rich world of literature, music, friendship, and tender sex, so different from his own desiccated, solitary life in a dreary tower-block, punctuated only by brief, mechanical relief between the outsize mutton thighs of a Stasi-commissioned prostitute. In his snooper’s hideaway in the attic of the apartment building, Wiesler sits transfixed by Dreyman’s rendition of a piano piece called “The Sonata of the Good Man”—a birthday present to the playwright from a dissident theater director who, banned by the culture minister from pursuing his vocation, subsequently commits suicide. Violating all the rules that he himself teaches at the Stasi’s own university, the secret watcher slips into the apartment and steals a volume of poems by Bertolt Brecht. Then we see him lying on a sofa, entranced by one of Brecht’s more elegiac verses.

In the role-reversing culmination of an intricate and gripping plot, the playwright’s girlfriend betrays him to the Stasi but the Stasi captain saves him from exposure and arrest—at the cost of his own subsequent career. He is reduced to steaming open letters in a Stasi cellar alongside a junior officer whom we see earlier telling a political joke in the ministry canteen and, in a chilling exchange, being asked for his name and rank by Colonel Grubitz.

After the Wall comes down, the playwright reads his Stasi file, works out from internal evidence how Wiesler—identified in the file as HGW XX/7—must have protected him, and writes a novel entitled, like the piece of music, The Sonata of the Good Man. The film ends with a cinematic haiku. The former Stasi man opens the newly published novel in the Karl Marx Bookshop in East Berlin—we are now in 1993—and discovers that it is dedicated to “HGW XX/7, in gratitude.” “Do you want it gift-wrapped?” asks the shop assistant. “No,” says Wiesler, “es ist für mich“—“it’s for me.” Punch line. End of story. Cut to credits.

Watching the film for the first time, I was powerfully affected. Yet I was also moved to object, from my own experience: “No! It was not really like that. This is all too highly colored, romantic, even melodramatic; in reality, it was all much grayer, more tawdry and banal.” The playwright, for example, in his smart brown corduroy suit and open-necked shirt, dresses, walks, and talks like a West German intellectual from Schwabing, a chic quarter of Munich, not an East German. Several details are also wrong. On everyday duty, Stasi officers would not have worn those smart dress uniforms, with polished knee-length leather boots, leather belts, and cavalry-style trousers. By contrast, the cadets in the Stasi university are shown in ordinary, student-type civilian clothes; they would have been in uniform. A Stasi surveillance team would have been most unlikely to install itself in the attic of the same building—a sure give-away to the residents, not all of whom could have been reliably silenced by the kind of chilling warning that Wiesler delivers to the playwright’s immediate neighbor across the stairwell: “One word to anyone and your Masha immediately loses her place to study medicine at university. Understood?”

Some of the language is also too high-flown, old-fashioned, and simply Western. A playwright who knew on which side his bread was buttered would never have used the West German word for blacklisting, Berufsverbot, in conversation with the culture minister. I never heard anyone in East Germany call a woman gnädige Frau, an old-fashioned term somewhere between “madam” and “my lady,” and a Stasi colonel would not have addressed Christa during an interrogation as gnädigste. I would bet my last Deutschmark that in 1984 a correspondent of the West German newsmagazine Der Spiegel would not have talked of Gesamtdeutschland.2 This strikes me as more the vocabulary of the uprooted German aristocracy among whom the director and writer Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck grew up—both of his parents fled from the eastern parts of the Reich at the end of the Second World War—than that of the real East Germany in 1984.

Advertisement

But these objections are in an important sense beside the point. The point is that this is a movie. It uses the syntax and conventions of Hollywood to convey to the widest possible audience some part of the truth about life under the Stasi, and the larger truths that experience revealed about human nature. It mixes historical fact (several of the Stasi locations are real and most of the terminology and tradecraft is accurate) with the ingredients of a fast-paced thriller and love story.

When I met von Donnersmarck in Oxford, where he studied politics, philosophy, and economics in the mid-1990s, I discussed my reservations with him. While fiercely defending the basic historical accuracy of the film, he immediately agreed that some details were deliberately altered for dramatic effect. Thus, he explained, if he had shown the Stasi cadets in uniform, no ordinary cinemagoer would have identified with them. But because he shows them (inaccurately) in student-type civilian dress and has one of them (implausibly) ask a naive question to the effect of “isn’t bullying people in interrogations wrong?,” the viewer can identify with them and is drawn into the story. He argued that in a movie the reality has always to be verdichtet, a word which means thickened, concentrated, intensified, but carries a verbal association with Dichtung, meaning poetry or, more broadly, fiction. Hence the elevated language (“I beg you, I beseech you”—ich flehe dich an—says the playwright at one point, asking his girlfriend not to submit again to the minister’s piggish lechery). Hence the luxuriant palette of rich greens, browns, and subtle grays in which the whole movie is shot, and the frankly operatic staging of Christa’s death.

During a subsequent question-and-answer session in an Oxford cinema the director mentioned, in separate answers, two films that he admired: Claude Lanzmann’s harrowing Holocaust documentary, Shoah, and Anthony Minghella’s version of The Talented Mr. Ripley—a thriller involving murder and stolen identity—which he singled out because “it doesn’t bore me, and for that I’m very grateful.” In The Lives of Others, Shoah meets The Talented Mr. Ripley. Von Donnersmarck does care about the historical facts, but he’s even more concerned not to bore us. And for that we are grateful. It is just because he is not an East German survivor but a fresh, cosmopolitan child of the Americanized West, a privileged Wessi down to the carefully unbuttoned tips of his pink button-down shirt, fluent in American-accented English and the universal language of Hollywood, that he is able to translate the East German experience into an idiom that catches the imagination of the world.

One of the finest film critics writing today, Anthony Lane, concludes his admiring review in The New Yorker by adapting Wiesler’s punch line: Es ist für mich. You might think that the film is aimed solely at modern Germans, Lane writes, but it’s not: Es ist für uns—it’s for us. He may be more right than he knows. The Lives of Others is a film very much intended for others. Like so much else made in Germany, it is designed to be exportable. Among its ideal foreign consumers are, precisely, Lane’s “us”—the readers of The New Yorker. Or, indeed, those of The New York Review.

Does anything essential get lost in this translation? The small inaccuracies and implausibilities are, on balance, justifiable artistic license, allowing a deeper truth to be conveyed. It does, however, lose something important: the sense of what Hannah Arendt famously called the banality of evil—and nowhere was evil more banal than in the net-curtained, plastic-wood cabins and caravans of the German Democratic Republic. Yet that is extraordinarily difficult to recreate, certainly for a wider audience, precisely because it was so banal, so unremittingly, mind-numbingly boring. (Or could a great screenwriter and director create a nonboring film about boredom? I lay down the challenge here.)

One of the movie’s central claims remains troubling. This is the idea, clearly implied in the ending, that the Stasi captain is the “good man” of the sonata. Now I have heard of Stasi informers who ended up protecting those they were informing on. I know of full-time Stasi operatives who became disillusioned, especially during the 1980s. And in many hours of talking to former Stasi officers, I never met a single one who I felt to be, simply and plainly, an evil man. Weak, blinkered, opportunistic, self-deceiving, yes; men who did evil things, most certainly; but always I glimpsed in them the remnants of what might have been, the good that could have grown in other circumstances.

Wiesler’s own conversion, as shown to us in the film, seems implausibly rapid and not fully convincing—despite a wonderfully enigmatic performance by the East German actor Ulrich Mühe. It would take more than the odd sonata and Brecht poem to thaw the driven puritan we are shown at the beginning. I find it interesting that in a contribution to the accompanying book (which also contains the original screenplay), the film’s historical adviser, Manfred Wilke, gives historical corroboration for many aspects of the film, but does not offer a single documented instance of a Stasi officer behaving in this way—and getting away with it. Instead he cites two cases of disaffected officers, a major in 1979 and a captain in 1981, both of whom were condemned to death and executed. Yet I’m prepared to accept that such a conversion and cover-up was just about within the realms of possibility. (If Colonel Grubitz had exposed Wiesler, he would have compromised himself.)

So Wiesler did one good thing, to set against the countless bad ones he had done before. But to leap from this to the notion that he was “a good man” is an artistic exaggeration—a Verdichtung—too far. In negotiating the treacherous moral maze of evaluating how people behave under dictatorships, there are two characteristic mistakes. One is the simplistic, black-and-white, Manichaean division into good guys and bad guys: X was an informer, so he must have been all bad, Y was a dissident, so she must have been all good. Anyone who has ever lived in such circumstances knows how much more complicated things are. The other, equal but opposite mistake is a moral relativism that ends up blurring the distinction between perpetrator and victim. This kind of moral relativism is frequently to be encountered among liberal-minded Westerners—and, not accidentally, often those who at the time viewed East Germany through rose-tinted spectacles. It is usually accompanied by the argument that the Stasi files cannot be trusted at all: die Akten lügen, the files lie. Von Donnersmarck himself is very far from this relativism, but his film steers uncomfortably close to it. Its “good man” is a Stasi captain who falsifies his reports to protect an artist.

This is a fault, but not a fatal one. The net effect of The Lives of Others will not, after all, be to unleash a wave of worldwide sympathy for former Stasi officers. It will be to bring home the horrors of that system, in a stylized fashion, to viewers who would have known little or nothing about them before. And this in a memorable, well-made movie. So it deserved the Oscar.

According to a report in Der Spiegel, when an emotional Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck finally arrived at a late-night German celebration following the award ceremony, he exclaimed, brandishing his Oscar statuette in the air, Wir sind Weltmeister! The phrase implies not masters of the world but world champions (as in soccer) or world masters (as in golf), with subsidiary connotations of artistic mastery, as in Meistersinger or Meisterwerk. But in what, exactly, are the Germans world masters? In soccer, almost. Their fine performance in last year’s World Cup produced scenes—unusual for postwar West Germany—of frankly patriotic celebration, and this was probably what von Donnersmarck had in mind. In the export business, certainly, whether it be BMWs to Britain, machine tools to Iran, assembly lines to China, or, just occasionally, films. The Lives of Others has already netted over $23 million worldwide—a nice little export earner for the German economy.

Some might be tempted to say, especially after watching this film, that Germany is also a world master in the production of cruel dictatorships. Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland— Death is a master from Germany—wrote Paul Celan in his incomparable post-Holocaust “Death Fugue.” In respect of fascism, Hitler’s Germany was undoubtedly the world champion—all too literally a world-beater. But can the same be said of Honecker’s Germany? Yes, this small country with just 17 million people was a kind of miniature masterpiece of psychological intimidation. As Orwell saw, the perfect totalitarian system is the one that does not need to kill or physically torture anyone. I am the last person to minimize the evils of the East German regime; but when set against the millions of deaths in Stalin’s gulag, Mao’s enforced famines, and Pol Pot’s genocide, it is hard to maintain that this was the worst that communism produced.

In that larger scheme of things, East Germany, unlike Nazi Germany, was but a sideshow. The Stasi was modeled on the KGB and not, as many people vaguely imagine, on the Gestapo. As the archives of other Soviet bloc states are opened, we find that their secret police worked in very similar ways. Perhaps the Stasi was that little bit better because it was, well, German; but there are so many larger horrors in the files of the KGB. And we should not forget that the subtle psychological terror of the Stasi state depended, from the first day to the last, on the presence of the Red Army and the willingness of the Soviet Union to use force. When that went, the Stasi state went too.

So why is it that the word “Stasi”—not “KGB,” “Red Guards,” or “Khmer Rouge”—is rapidly becoming a global synonym for communist terror? Because the enterprise in which the Germans truly are Weltmeister is the cultural reproduction of their country’s versions of terror. No nation has been more brilliant, more persistent, and more innovative in the investigation, communication, and representation—the re-presentation, and re-re-presentation—of its own past evils.

This cultural reproduction has to do with the character of both the perpetrators and the victims. In Hitler’s holocaust, the people of Gutenberg set out to exterminate the people of the book. One of Europe’s most talented, profound, creative nations tried to destroy another, with which it had lived in an intense, fecund cultural symbiosis for many years. (“The Germans are a bad love of the Jews,” a Polish peasant woodcarver once observed to a friend of mine.) Afterward, both nations memorialized the horror with a meticulousness and an artistry never before seen. In Celan’s “Death Fugue,” a German poem that whispers with echoes of Hasidic mysticism, that memorialization was itself a new triumph—a living forward out of death—of the German-Jewish symbiosis. Celan himself spoke of how the German language that he loved had survived “the thousand darknesses of death-bringing speech” (die tausend Finsternisse todbringender Rede). Now that language lived again through him, who had himself just eluded the master from Germany.

In the case of communism, the Germans did it to themselves—though not in a sovereign state. The people of Gutenberg oppressed the people of Luther. As soon as it was over, the people of Ranke took up the story. A generation of West German contemporary historians, trained in the study of Nazism, turned their skilled attentions to the GDR, and especially to the dissection of the Stasi. Only the existence and character of West Germany, with its fiercely moral and professional approach to dealing with a difficult past, explains the unique cultural transmission of the Stasi phenomenon. (Imagine that the former Soviet Union had been taken over by a democratic West Russia, equipped and motivated to expose all the evils of the KGB.) And now we have the movie version, produced by a thoroughly Americanized young West German.

Each stage of this process builds on the last. Cognitive scientists tell us that the repetition of words and images strengthens the synapses connecting the neurons in the neural circuits that compute, in our heads, the meaning of those words and images. With time, these mental associations become electrochemically hard-wired. Whether intentionally or not, The Lives of Others plugs straight into these preexisting connections in our minds. Take that apparently trivial detail of the Stasi officers’ dress uniforms. Why does it matter? Because the sight of Germans in Prussian gray, with long, shining leather boots, shrieks to our synapses: Nazis.

One is then not at all surprised to discover that the actor who portrays Wiesler’s sinister superior, Colonel Grubitz, made his reputation back in 1984—the year the film is set—playing, on a West German stage, the role of an SS man. The real everyday Stasi uniforms, dreary numbers made of bargain-basement terylene, completed by cheap mailman’s boots, would not have the same effect. In the theatrical way they are shot, the scenes of the playwright Dreyman dancing around the culture minister reminded me strongly of Mephisto, István Szabó’s brilliant film about the actor-director Gustaf Gründgens, and his Faustian pact with Hermann Goering. Another circuit of Nazi-Stasi associations is involuntarily fired.

Then there is the pivotal moment when Dreyman plays the classical “Sonata of the Good Man” on the piano, while Wiesler listens on his headphones. After he finishes, Dreyman turns to Christa and exclaims, “Can anyone who has heard this music, I mean really heard it, still be a bad person?” Von Donnersmarck says he was inspired by a passage in which Maxim Gorky records Lenin saying that he can’t listen to Beethoven’s Appassionata because it makes him want to say sweet, silly things and pat the heads of little people, whereas in fact those little heads must be beaten, beaten mercilessly, to make the revolution. As a first-year film student, von Donnersmarck wondered “what if one could force a Lenin to hear the Appassionata,” and that was the original germ of his movie. (Dreyman actually refers to Lenin’s remark.)

So the inspiration for this scene was Russian. But what are the connections that we—especially we of Lane’s “us”—instantly make as we watch? Surely we think of Roman Polanski’s The Pianist, with the German officer deeply affected by the Polish Jewish pianist’s playing of Chopin, and therefore sparing his life—as Wiesler now spares Dreyman. Surely we think, too, of the educated Nazi killers who in the evening listened to the music of Mendelssohn, then went out the next morning to murder more Mendelssohns. Did they not really hear the music? Does high culture humanize? We are back with the deepest twentieth-century German conundrum, conveyed most movingly in music and poetry. Such are the synaptic connections that make The Lives of Others resonate so powerfully in our heads.

The Germany in which this film was produced, in the early years of the twenty-first century, is one of the most free and civilized countries on earth. In this Germany, human rights and civil liberties are today more jealously and effectively protected than (it pains me to say) in traditional homelands of liberty such as Britain and the United States. In this good land, the professionalism of its historians, the investigative skills of its journalists, the seriousness of its parliamentarians, the generosity of its funders, the idealism of its priests and moralists, the creative genius of its writers, and, yes, the brilliance of its filmmakers have all combined to cement in the world’s imagination the most indelible association of Germany with evil. Yet without these efforts, Germany would never have become such a good land. In all the annals of human culture, has there ever been a more paradoxical achievement?

This Issue

May 31, 2007

-

1

“Und willst Du nicht mein Bruder sein…” Die DDR heute (Reinbek: Rowohlt, 1981). Parts appeared in English in The Uses of Adversity: Essays on the Fate of Central Europe (Random House, 1989). ↩

-

2

A postwar term for Germany as a whole, sometimes intended to include not just East Germany but also the former German eastern territories, such as Silesia, given to Poland after 1945. ↩