1.

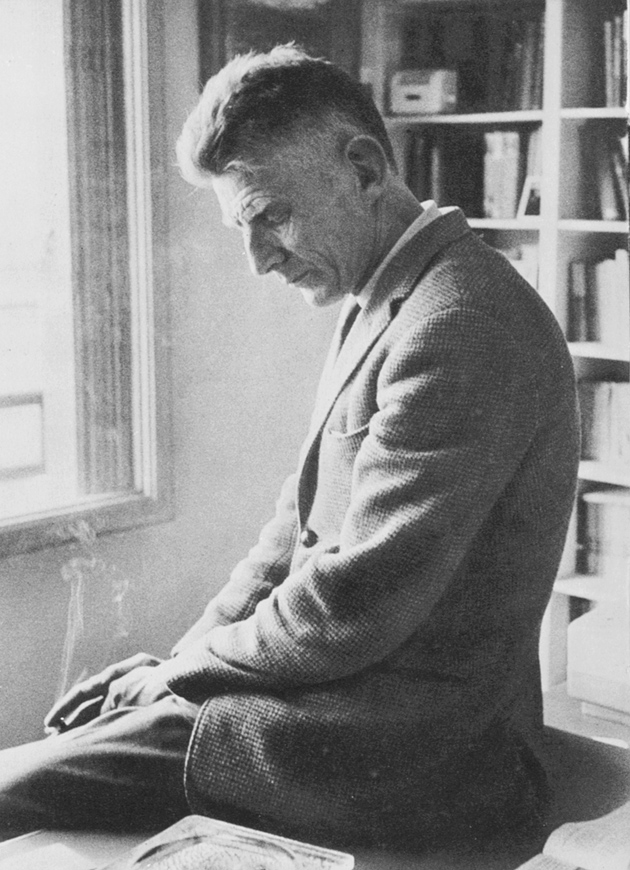

In 1923 Samuel Barclay Beckett, aged seventeen, was admitted to Trinity College, Dublin, to study Romance languages. He proved an exceptional student, and was taken under the wing of Thomas Rudmose-Brown, professor of French, who did all he could to advance the young man’s career, securing for him on graduation first a visiting lectureship at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in Paris, then a position back at Trinity College.

After a year and a half at Trinity, performing what he called the “grotesque comedy of lecturing,” Beckett resigned and fled back to Paris. Yet even after this letdown, Rudmose-Brown did not give up on his protégé. As late as 1937 he was still trying to nudge Beckett back into the academy, persuading him to apply for a lectureship in Italian at the University of Cape Town. “I may say without exaggeration,” he wrote in a supporting letter, “that as well as possessing a sound academic knowledge of the Italian, French and German languages, [Mr Beckett] has remarkable creative faculty.” In a postscript he added: “Mr Beckett has an adequate knowledge of Provençal, ancient and modern.”

Beckett felt genuine fondness and respect for Rudmose-Brown, a Racine specialist with an interest in the contemporary French literary scene. Beckett’s first book, a monograph on Proust (1931), though commissioned as a general introduction to this challenging new writer, reads more like an essay by a superior graduate student intent on impressing his professor. Beckett himself had severe doubts about the book. Rereading it, he “wondered what [he] was talking about,” as he confided to his friend Thomas McGreevy. It seemed to be “a distorted steam-rolled equivalent of some aspect or confusion of aspects of myself…tied somehow on to Proust…. Not that I care. I don’t want to be a professor.”

What dismayed Beckett most about professorial life was teaching. Day after day this shy, taciturn young man had to confront in the classroom the sons and daughters of Ireland’s Protestant middle class, and persuade them that Ronsard and Stendhal were worthy of their attention. “He was a very impersonal lecturer,” reminisced one of his better students. “He said what he had to say and then left the lecture room…. I believe he considered himself a bad lecturer and that makes me sad because he was so good…. Many of his students would, unfortunately, agree with him.” “The thought of teaching again paralyses me,” Beckett wrote to McGreevy from Trinity in 1931 as a new term approached. “I think I will go to Hamburg as soon as I get my Easter cheque…and perhaps hope for the courage to break away.” It took another year before he found that courage. “Of course I’ll probably crawl back with my tail coiled round my ruined poenis [sic],” he wrote to McGreevy. “And maybe I wont.”

The Trinity College lectureship was the last regular job Beckett held. Until the outbreak of war, and to an extent during the war too, he relied on an allowance from the estate of his father, who died in 1933, plus occasional handouts from his mother and elder brother. Where he could find it, he took on translation work and reviewing. The two pieces of fiction he published in the 1930s—the stories More Pricks Than Kicks (1934) and the novel Murphy (1938)—brought in little in the way of royalties. He was almost always short of money. His mother’s strategy, as he observed to McGreevy, was “to keep me tight so that I may be goaded into salaried employment. Which reads more bitterly than it is intended.”

Footloose artists like Beckett tended to keep an eye on exchange rates. The cheap franc after World War I had made France an attractive destination. An influx of foreign artists, including Americans living on dollar remittances, turned Paris of the 1920s into the headquarters of international Modernism. When the franc climbed in the early 1930s the transients took flight, leaving only diehard exiles like James Joyce behind.

Migrations of artists are only crudely related to fluctuations in exchange rates. Nevertheless, it is no coincidence that in 1937, after a new devaluation of the franc, Beckett found himself in a position to quit Ireland and return to Paris. Money is a recurrent theme in his letters, particularly toward the end of the month. His letters from Paris are full of anxious notations about what he can and cannot afford (hotel rooms, meals). Though he never starved, he lived a genteel version of a hand-to-mouth existence. Books and paintings were his sole personal indulgence. In Dublin he borrows £30 to buy a painting by Jack Butler Yeats, brother of William Butler Yeats, that he cannot resist. In Munich he buys the complete works of Kant in eleven volumes.

Advertisement

What £30 in 1936 represents in today’s terms, or the 19.75 francs that an alarmed young man had to pay for a meal at the restaurant Ste. Cécile on October 27, 1937, is not readily computed, but such expenditures had real significance to Beckett, even an emotional significance. In a volume with such lavish editorial aids as the new edition of his letters, it would be good to have more guidance on monetary equivalents. Less discretion about how much Beckett received from his father’s estate would be welcome too.

Among the jobs that Beckett contemplated were: office work (in his father’s quantity surveying firm); language instruction (in a Berlitz school in Switzerland); school teaching (in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia); advertising copywriting (in London); piloting commercial aircraft (in the skies); interpreting (between French and English); and managing a country estate. There are signs that he would have taken the position in Cape Town had it been offered (it was not); through contacts at the then University of Buffalo he also drops hints that he might look kindly on an offer from that quarter (it did not come).

The career that he fancied most of all was in cinema. “How I would like to go to Moscow and work under Eisenstein for a year,” he writes to McGreevy. “What I would learn under a person like Pudovkin,” he continues a week later, “is how to handle a camera, the higher trucs of the editing bench, & so on, of which I know as little as of quantity surveying.” In 1936 he actually sends a letter to Sergei Eisenstein:

I write to you…to ask to be considered for admission to the Moscow State School of Cinematography…. I have no experience of studio work and it is naturally in the scenario and editing end of the subject that I am most interested…. [I] beg you to consider me a serious cinéaste worthy of admission to your school. I could stay a year at least.

Despite receiving no reply, Beckett informs McGreevy he will “probably go [to Moscow] soon.”

How is one to regard plans to study screenwriting in the USSR in the depths of the Stalinist night: as breathtaking naiveté or as serene indifference to politics? In the age of Stalin and Mussolini and Hitler, of the Great Depression and the Spanish civil war, references to world affairs in Beckett’s letters can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

There is no doubt that, politically speaking, Beckett’s heart was in the right place. His contempt for anti-Semites, high and low, comes out clearly in his letters from Germany. “If there is a war,” he informs McGreevy in 1939, “I shall place myself at the disposition of this country”—“this country” being France, Beckett being a citizen of neutral Ireland. (He would indeed go on to risk his life in the French Resistance.) But questions about how the world should be run do not seem to interest him much. One searches the letters in vain for thoughts on the place of the writer in society. A dictum he quotes from a favorite philosopher, the second-generation Cartesian Arnold Geulincx (1624–1669), suggests his overall stance toward the political: ubi nihil vales, ibi nihil velis, which may be glossed: Don’t invest hope or longing in an arena where you have no power.

It is only when the subject of Ireland comes up that Beckett now and again allows himself to vent a political opinion. Though McGreevy was an Irish nationalist and a devout Catholic, and Beckett an agnostic cosmopolite, the two rarely allowed politics or religion to come between them. But an essay by McGreevy on Jack Butler Yeats provokes Beckett to a fit of ire. “For an essay of such brevity the political and social analyses are rather on the long side,” he writes.

I received almost the impression…that your interest was passing from the man himself to the forces that formed him…. But perhaps that…is the fault of…my chronic inability to understand as member of any proposition a phrase like “the Irish people,” or to imagine that it ever gave a fart in its corduroys for any form of art whatsoever,…or that it was ever capable of any thought or act other than the rudimentary thoughts and acts belted into it by the priests and by the demagogues in service of the priests, or that it will ever care…that there was once a painter in Ireland called Jack Butler Yeats.

2.

Beckett’s letters are packed with comments on artworks he has seen, music he has heard, books he has read. Among the earlier of these, some are just silly, the pronouncements of a cocky tyro—“Beethoven’s Quartets are a waste of time,” for example. Among the writers who have to endure the lash of his youthful scorn are Balzac (“The bathos of style & thought [in Cousine Bette] is so enormous that I wonder is he writing seriously or in parody”) and Goethe (than whose drama Tasso “anything more disgusting would be hard to devise”). Apart from forays into the Dublin literary scene, his reading tends to be among the illustrious dead. Of English novelists, Henry Fielding and Jane Austen win his favor, Fielding for the freedom with which he interjects his authorial self into his stories (a practice Beckett himself takes over in Murphy). Ariosto, Sainte-Beuve, and Hölderlin also get approving nods.

Advertisement

One of the more unexpected of his literary enthusiasms is for Samuel Johnson. Struck by the “mad terrified face” in the portrait by James Barry, he comes up in 1936 with the idea of turning the story of Johnson’s relationship with Hester Thrale into a stage play. It is not the great pontificator of Boswell’s Life who engages him, as the letters make clear, but the man who struggled all his life against indolence and the black dog of depression. In Beckett’s version of events, Johnson takes up residence with the much younger Hester and her husband at a time when he is already impotent and therefore doomed to be a “Platonic gigolo” in the ménage à trois. He suffers first the despair of “the lover with nothing to love with,” then heartbreak when the husband dies and Hester goes off with another man.

In the confident public man who privately struggles against listlessness and depression, who sees no point in living yet cannot face annihilation, Beckett clearly detects a kindred spirit. Yet after an initial flurry of excitement over the Johnson project, his own indolence supervenes. Three years pass before he puts pen to paper; halfway through Act I he abandons the work.1

Before he discovered Johnson, the writer whom Beckett had elected to identify with was the famously active and productive James Joyce, Shem the Penman. His own early writing, as he cheerfully admits, “stinks of Joyce.” But only a handful of letters passed between Beckett and Joyce. The reason is simple: during the times when they were closest (1928–1930, 1937–1940)—times when Beckett acted as Joyce’s occasional secretary and general dogsbody—they were living in the same city, Paris. Between these two periods their relations were strained and they did not communicate. The cause of the strain was Beckett’s treatment of Joyce’s daughter Lucia, who was infatuated with him. Though alarmed by Lucia’s evident instability of mind, Beckett, much to his discredit, allowed the relationship to develop. When he finally broke it off, Nora Joyce was furious, accusing him—with some justice—of exploiting the daughter to maintain access to the father.

It was probably not a bad thing for Beckett to be expelled from this dangerous Oedipal territory. By the time he was reenlisted, in 1937, to help with the proofreading of Work in Progress (later Finnegans Wake), his attitude toward the master had become less fraught, more charitable. To McGreevy he confides:

Joyce paid me 250 fr. for about 15 hrs. work on his proofs…. He then supplemented it with an old overcoat and 5 ties! I did not refuse. It is so much simpler to be hurt than to hurt.

And again, two weeks later:

He [Joyce] was sublime last night, deprecating with the utmost conviction his lack of talent. I don’t feel the danger of the association any more. He is just a very lovable human being.

The night after he wrote these words Beckett got into a scuffle with a stranger in a Paris street and was stabbed. The knife just missed his lungs; he had to spend two weeks in the hospital. The Joyces did everything they could to help their young compatriot, having him moved to a private ward, bringing him custard puddings. Reports of the assault made it into the Irish newspapers; Beckett’s mother and brother traveled to Paris to be at his bedside. Among other unexpected visitors was a woman Beckett had met years earlier, Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil, who would in due course become his companion and then his wife.

The aftermath of the assault, reported to McGreevy with some bemusement, seems to have revealed to Beckett that he was not as alone in the world as he liked to believe; even more curiously, it seemed to confirm him in his decision to make Paris his home.

Though Beckett’s literary output during the twelve years covered by these letters is fairly thin—the Proust monograph; an apprentice novel, A Dream of Fair to Middling Women, disowned and not published during his lifetime; the stories More Pricks Than Kicks ; Murphy ; a volume of poems; some book reviews—he is far from inactive. He reads extensively in philosophy from the pre-Socratics to Schopenhauer. On Schopenhauer he reports: “A pleasure…to find a philosopher that can be read like a poet, with an entire indifference to the apriori forms of verification.” He works intensively on Geulincx, reading his Ethics in the original Latin: his study notes have recently been unearthed and published as a companion to a new English translation.2

A rereading of Thomas à Kempis elicits pages of self-scrutiny. The danger of Thomas’s quietism for someone who, like himself, lacks religious faith (“I…seem never to have had the least faculty or disposition for the supernatural”) is that it can confirm him in an “isolationism” that is, paradoxically, not Christlike but Luciferian. Yet is it fair to take Thomas as a purely ethical guide, stripping him of any transcendental dimension? In his own case, how can an ethical code save him from the “sweats & shudders & panics & rages & rigors & heart burstings” that he suffers?

“For years I was unhappy, consciously & deliberately,” he continues to McGreevy in language notable for its directness (gone are the cryptic jokes and faux Gallicisms of the early letters).

I isolated myself more & more, undertook less & less & lent myself to a crescendo of disparagement of others & myself…. In all that there was nothing that struck me as morbid. The misery & solitude & apathy & the sneers were the elements of an index of superiority…. It was not until that way of living, or rather negation of living, developed such terrifying physical symptoms that it could no longer be pursued, that I became aware of anything morbid in myself.

The crisis to which Beckett alludes, the mounting sweats and shudders, had arrived in 1933, when after the death of his father his own health, physical and mental, deteriorated to a point where his family became concerned. He suffered from heart palpitations and had nocturnal panic attacks so severe that his elder brother had to sleep in his bed to calm him. By day he kept to his room, lying with his face to the wall, refusing to speak, refusing to eat.

A doctor friend had suggested psychotherapy, and his mother offered to pay. Beckett consented. Since the practice of psychoanalysis was not yet legal in Ireland, he moved to London, where he became a patient of Wilfrid Bion, some ten years his senior and at the time a trainee therapist at the Tavistock Institute. In the course of 1934–1935 he met with Bion several hundred times. Though his letters reveal little about the content of their sessions, they make it clear he liked and respected him.

Bion concentrated on his patient’s relations with his mother, May Beckett, against whom he was consumed by pent-up rages yet from whom he was unable to cut himself loose. Beckett’s own way of putting it was that he had not been properly born. Under Bion’s guidance he achieved a regression to what in an interview late in life he called “intrauterine memories” of “feeling trapped, of being imprisoned and unable to escape, of crying to be let out but no one could hear, no one was listening.”

The two-year analysis was successful insofar as it freed Beckett of his symptoms, though these threatened to resurface when he visited the family home. A 1937 letter to McGreevy suggests that he had yet to make his peace with his mother. “I don’t wish her anything at all, neither good nor ill,” he writes.

I am what her savage loving has made me, and it is good that one of us should accept that finally…. I simply don’t want to see her or write to her or hear from her…. If a telegram came now to say she was dead, I would not do the Furies the favour of regarding myself even as indirectly responsible.

Which I suppose all boils down to saying what a bad son I am. Then Amen.

Beckett’s novel Murphy, completed in 1936, the first work in which this chronically self-doubting author seems to have taken genuine if transient creative pride (before long, however, he would be dismissing it as “a very dull work, painstaking, creditable & dull”), draws on his experience of the London therapeutic milieu and on his reading in the psychoanalytic literature of the day. Its hero is a young Irishman who, exploring spiritual techniques of withdrawal from the world, achieves his goal when he inadvertently kills himself. Light in tone, the novel is Beckett’s response to the therapeutic orthodoxy that the patient should learn to engage with the larger world on the world’s terms. In Murphy, and even more in Beckett’s mature fiction, heart palpitations and panic attacks, fear and trembling or willed oblivion, are entirely appropriate responses to our existential situation.

Wilfrid Bion went on to make a considerable mark on psychoanalysis. During World War II he pioneered group therapy among soldiers returning from front-line duty (he had himself suffered battle trauma in World War I: “I died—on August 8th 1918,” he wrote in his memoirs). After the war he underwent analysis with Melanie Klein. Though his most important writings were to be on the epistemology of transactions between analyst and patient, for which he developed an idiosyncratic algebraic notation that he called “the Grid,” he continued to work with psychotic patients experiencing irrational dread, psychic death.

Attention has been given of late, by both literary critics and psychoanalysts, to Beckett and Bion and what influence they might have had on each other. Of what actually passed between them we have no record. Nevertheless, one can venture to say that psychoanalysis of the kind that Beckett underwent with Bion—what one might call proto-Kleinian analysis—was an important passage in his life, not so much because it relieved (or appears to have relieved) his crippling symptoms or because it helped (or appears to have helped) him to break with his mother, but because it confronted him, in the person of an interlocutor or interrogator or antagonist in many ways his intellectual equal, with a new model of thinking and an unfamiliar mode of dialogue.

Specifically, Bion challenged Beckett—whose devotion to the Cartesians shows how much he had invested in the notion of a private, inviolable, nonphysical mental realm—to reevaluate the priority he gave to pure thought. Bion’s Grid, which accords phantasy processes their full due in mental activity, is in effect an analytic deconstruction of the Cartesian model of thinking. In the psychic menagerie of Bion and Klein, Beckett may also have found hints for the protohuman organisms, the worms and bodiless heads in pots, that populate his various underworlds.

Bion seems to have empathized with the need felt by creative personalities of Beckett’s type to regress to prerational darkness and chaos as a preliminary to an act of creation. Bion’s major theoretical work, Attention and Interpretation (1970), describes a mode of presence of analyst to patient, stripped of all authority and directedness, that is much the same (minus the jokes) as that adopted by the mature Beckett toward the phantom beings who speak through him. Bion writes:

To attain the state of mind essential for the practice of psycho-analysis I avoid any exercise of memory; I make no notes…. If I find that I am without any clue to what the patient is doing and am tempted to feel that this secret lies hidden in something I have forgotten, I resist any impulse to remember….

A similar procedure is followed with regard to desires: I avoid entertaining desires and attempt to dismiss them from my mind….

By rendering oneself “artificially blind” [a phrase that Bion quotes from Freud] through the exclusion of memory and desire, one achieves…the piercing shaft of darkness [that] can be directed on the dark features of the analytic situation.

3.

While the decade of the 1930s may have felt to Beckett like years of blockage and sterility, we can in retrospect see that they were being used by deeper forces within him to lay the artistic and philosophical—and perhaps even experiential—foundations of the great creative outburst that came in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Despite the idleness for which he continually castigates himself, Beckett did an enormous amount of reading. But his self-education was not just literary. In the course of the 1930s he turned himself into a formidable connoisseur of painting, with a concentration on medieval Germany and the Dutch seventeenth century. The letters from his six-month visit to Germany are overwhelmingly about art—about paintings he has seen in museums and galleries or, in the cases of artists not allowed to exhibit publicly, in their studios. These letters are of unique interest, giving an intimate glimpse into the art world in Germany at the peak of the Nazi offensive against “degenerate art” and “Art-Bolshevism.”

The moment of breakthrough in Beckett’s aesthetic Bildung comes during the German visit, when he realizes he is able to enter into dialogue with paintings on their own terms, unmediated by words. “I used never to be happy with a picture till it was literature,” he writes to McGreevy in 1936, “but now that need is gone.”

His guide here is Cézanne, who came to see the natural landscape as “unapproachably alien,” an “unintelligible arrangement of atoms,” and had the wisdom not to intrude himself into its alienness. In Cézanne “there is no entrance anymore nor any commerce with the forest, its dimensions are its secret & it has no communications to make,” Beckett writes. A week later he pushes the insight further: Cézanne has a sense of his own incommensurability not only with the landscape but—on the evidence of his self-portraits—with “the life…operative in himself.” Herewith the first authentic note of Beckett’s mature, post-humanist phase is struck.

4.

It was to some degree a matter of chance that the Irishman Samuel Beckett should have ended his life as one of the masters of modern French letters. As a child he was sent to a bilingual French-English school not because his parents wished to prepare him for a literary career but because of the social prestige of French. He excelled in French because he had a talent for languages, and when he studied them did so diligently. Thus there was no pressing reason why in his twenties he should have learned German, beyond the fact that he had fallen in love with a cousin who lived in Germany; yet he worked up his German to a point where he could not only read the German classics but also write correct if stiff formal German himself. Similarly he learned Spanish well enough to publish a body of Mexican poetry in English translation.

One of the recurring questions about Beckett is why he turned from English to French as his main literary language. On this subject a revealing document is a letter he wrote, in German, to a young man named Axel Kaun whom he had met during his 1936–1937 tour of Germany. In the frankness with which it addresses his own literary ambitions, this letter to a comparative stranger comes as a surprise: even to McGreevy he is not so ready to explain himself.

To Kaun he describes language as a veil that the modern writer needs to tear apart if he wants to reach what lies beyond, even if what lies beyond may only be silence and nothingness. In this respect writers have lagged behind painters and musicians (he points to Beethoven and the silences in his scores). Gertrude Stein, with her minimalist verbal style, has the right idea, whereas Joyce is moving in quite the wrong direction, toward “an apotheosis of the word.”

Though Beckett does not explain to Kaun why French should be a better vehicle than English for the “literature of the non-word” that he looks forward to, he identifies ” offizielles Englisch,” formal or cultivated English, as the greatest obstacle to his ambitions. A year later he has begun to leave English behind, composing his new poems in French.

5.

Beckett’s closest and most faithful correspondent outside his family is Thomas McGreevy, whom he first met in Paris in 1928. James Knowlson, Beckett’s biographer, describes McGreevy as

a dapper little man with a twinkling sense of humour [who]…conveyed an impression of elegance, even when, as was often the case, he was virtually penniless…. He was as confident, talkative, and gregarious as Beckett was diffident, silent, and solitary.

Though McGreevy was the older by thirteen years, the two hit it off at once. But their itinerant lifestyles meant that, for much of the time—and to the great good fortune of posterity—they could keep in touch only via the mails. For a decade they exchanged letters on a regular, sometimes weekly, basis. Then, for unexplained reasons (the relevant letter from McGreevy has been lost), their correspondence tailed off.

McGreevy was a poet and critic, author of an early study of T.S. Eliot. After his Poems of 1934 he more or less abandoned poetry, devoting himself to art criticism and later to his work as director of the National Gallery in Dublin. In Ireland there has recently been a revival of interest in him, though less for his attainments as a poet, which are slight, than for his efforts to import the practices of international Modernism into the introverted world of Irish poetry. Beckett’s own feelings about McGreevy’s poems were mixed. He approved of his friend’s avant-garde poetics, but was discreetly noncommittal about his Catholic and Irish nationalist bent.

Volume I of the letters includes over a hundred to McGreevy, plus excerpts from another fifty. No other correspondent is represented on a comparable scale. Of letters to women with whom Beckett was sentimentally involved, only a handful are reproduced, none particularly intimate, some marred by a labored facetiousness of style. The reason why what we can loosely call private correspondence is excluded from the volume is straightforward: when Beckett consented to publication, he made a stipulation—a stipulation endorsed by the Beckett estate and adhered to by the present editors—that his letters would be “[reduced] to those passages only having bearing on [his] work.”

The problem is of course that in the case of a great writer, or a writer exposed to such close critical scrutiny as Beckett has been, every word he pens can be read as having a bearing on his work. No doubt the day will arrive when, all legal restrictions having expired, the distinction between literary and private will be dropped and the entire archive thrown open. In the meantime, in this volume and the three to come, we will have to content ourselves with a selection that—so the editors promise—will comprise some 2,500 letters, with extracts from another 5,000.

The editorial work behind this project has been immense in scale. Every book that Beckett mentions, every painting, every piece of music is tracked down and accounted for. His movements are traced from week to week. Everyone he alludes to is identified; his principal contacts earn potted biographies. When he writes in a foreign language, we are given both the original and an English translation (save for some French verse that is left untranslated—a puzzling editorial decision). By page count, some two thirds of the volume is given over to scholarly apparatus, principally elucidatory commentary. The standard of the commentary is of the highest. I have come across only one slip-up: Beckett’s dislike of Franco, the Spanish generalissimo, is represented as a dislike of France.3 Within the constraints laid down by Beckett himself, The Letters of Samuel Beckett is a model edition.

This Issue

April 30, 2009

-

1

The notebooks for the Johnson play are preserved at the University of Reading. The surviving dramatic fragment has been published in Samuel Beckett, Disjecta: Miscellaneous Writings and a Dramatic Fragment, edited by Ruby Cohn (Grove, 1984). ↩

-

2

Arnold Geulincx, Ethics, with Samuel Beckett’s Notes, translated by Martin Wilson, edited by Han von Ruler, Anthony Uhlmann, and Martin Wilson (Leiden: Brill, 2006). ↩

-

3

The claim that the town of Graaff Reinet in South Africa is “near Cape Town” may also qualify as a slip-up. It is in fact some 650 kilometers distant. ↩