In the late 1990s, Chinese peasants in the village of Da Fo, many of whom between 1959 and 1961 had survived the twentieth century’s greatest famine, felt free enough to install shrines to Guangong, the traditional war god of resistance to oppressive rulers. Some were reading The Water Margin, an epic of peasant uprisings a thousand years ago against corrupt officials. They consulted late Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) geomancy manuals that predicted a sixty-year cycle of apocalypse and rebellion. The manuals were banned by the local security officials, who understood perfectly what the Da Fo villagers, known for over fifty years as a “headache,” had on their minds.

To summarize their feelings briefly: “Village people…had come to associate socialism with starvation and the agents of the party-state with the specter of death.” Such is the final judgment of Ralph Thaxton, professor of politics at Brandeis and the author of Catastrophe and Contention in Rural China, a horrifying and convincing condemnation of the Maoist programs that during the Great Leap Forward caused starvation among the rural population between 1959 and 1961 and beyond. Over almost twenty years Thaxton interviewed four hundred residents of Da Fo, in Henan province, people who had been traumatized by years of famine, humiliation, torture, and death. He records, too, how the Communist Party proscribed their traditional practices—not only weddings and other celebrations, but funerals; villagers feared that as a result the “famine-corpse ghosts” of the improperly buried dead were bringing misfortune to the surviving members of their families.

As he explored Da Fo between 1989 and 2007, Thaxton uncovered how the elements of Communist rule—autocratic, brutal, corrupt, and mean-spirited—combined with the plunder, forced labor, and starvation of the famine itself to turn the Da Fo villagers against the Party. They had once trusted it, but their grim experiences conditioned them, Thaxton writes, “to think about their relationship with the Communist Party in ways that do not bode well for the continuity of socialist rule.” If there is another book that shows more profoundly how Mao, whose portrait still hangs in Tiananmen Square, inflicted disaster on a particular place, I haven’t read it.

Only two other books I know of dig as deeply over many years into how the disasters of the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution were experienced on the local level: Chinese Village, Socialist State and Revolution, Resistance, and Reform in Village China, both by the same authors.1 Magnificent and groundbreaking as those works are, their authors studied a model village, Wugong, that received secret help from the central government. Nonetheless, Wugong’s experience was ghastly enough; indeed, much of its experience was similar to Da Fo’s.

Da Fo is not the actual name of Thaxton’s village, something he makes plain only in a footnote; nor does he give real names to its inhabitants. Despite the willingness of many to talk to foreigners, the fear of the Communist authorities among rural residents remains intense.2 Still, the villagers recount how the Communist Party appeared in Da Fo in 1937 and its members led the local fight against the Japanese and then Chiang Kaishek’s Kuomintang (KMT). The Party helped the villagers survive the nationwide famine of 1942 and when it came into control in Da Fo it briefly lowered peasants’ taxes. In Da Fo, as throughout China, Mao and the Communist Party were regarded as saviors.

But the victors of those struggles were often brutal young men, and it was they, spurred on by Mao’s dogmas, who enforced the harsh demands of the Great Leap, which resulted in one calamity after another. Because of those calamities, the Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976 played out in Da Fo in ways not usually associated with what Chinese call “the terrible decade,” for it punished some local bosses who had acted viciously. Thaxton says that many years after the famine, peasants still remember the young men who were village leaders as “poorly endowed, uneducated, quick-tempered, perfidious hustlers and ruffians who more often than not operated in an arbitrary and brutal political manner in the name of the Communist Party.”

The worst of them, Bao Zhilong, an illiterate native of Da Fo (Thaxton asked him to write his name and he failed), was an all too typical low-level Maoist official: he had suffered and dealt out suffering in the wars against the Japanese and the KMT. Deeply corrupt and sadistic, Bao developed a taste for bullying and violence. Very resilient, he bounced back from Party disciplinary procedures, as well as from the revenge taken against him during the Cultural Revolution.

Thaxton doesn’t excuse Bao and his confederates because they had suffered. Their past, he suggests,

Advertisement

was placed in a cultural myth…the myth of the war god Guangong and his heroism. This myth, which emphasized the ability to survive violent extremity…, was somehow connected to the ideas Bao and many of his militia activists held about pride and personal accomplishment.

Such men, Thaxton observes, gave no sign that they had any qualms when they abused, tortured, and killed others. They did it because they could and because Mao, the Great Helmsman and Teacher, wanted them to. Thaxton is right to compare them, as they strove “to tear apart civil society and destroy human purpose,” to the Cambodian Khmer Rouge and the Sudanese Janjaweed.

The Korean War and China’s isolation from most of the rest of the world accelerated Mao’s attacks on his perceived enemies and sped up his plans to develop an economy in which the government would benefit from maximum rural taxation. Before that, Da Fo’s peasants had tilled their own small holdings and observed their traditional practices connected to markets—festivals, banquets, and honoring ancestors. The Party renewed another profitable sideline, forbidden by the KMT, of extracting and selling salt from earth. Beginning in 1954 the peasants were encouraged to form and join collectives, which, they told Thaxton, increased their efficiency without taking away their land or curtailing their livelihoods. By 1958 private ownership, however, had been abolished and households all over China were forced into the state-operated communes. Mao insisted that the communes must produce more grain for the cities and earn foreign exchange from exports.

The government’s senior economist, Chen Yun, warned fruitlessly that peasants would not welcome these arrangements and might rebel against them. At the provincial level a similar debate ended with the purging of Henan’s Party secretary, who had urged moderation in the administration of the cooperatives and the communes. This purge, writes Thaxton, convinced men like Bao Zhilong to “fear political exile or worse if they brooked any protest of Mao’s Great Leap plans.”

Thaxton in his meticulous way explains how this ban on private holdings wrecked peasant life at its most basic level, namely the ability to secure enough food to go on living: traditionally, peasants owning their own land could rent or sell it, use it as collateral for loans, or even dismantle and sell parts of their houses. Once the commune was operational Bao and his colleagues swung into manic action, herding villagers into the fields to sleep and to work intolerable hours, and forcing them to walk, starving, to distant additional projects.

Boss Bao and his men beat and occasionally killed those they deemed uncooperative. For all this, the villagers were given increasingly meager supplies of food, to be consumed in public dining halls. As they raced toward famine, Bao linked himself to “Mao’s deadly project using a combination of physical and verbal abuse, deprivation, and terror.” An ex-leader of that project told Thaxton in 2001, “I never questioned it, nor did any of the other party leaders. We had unshakeable confidence in the Communist Party and the leadership of Chairman Mao.”

Simply put, a principal cause of the famine was overreporting of harvest sizes. Wanting these inflated statistics to be true, the government seized what was purported to be a reasonable amount of the harvest, leaving the peasants with less grain than necessary to survive. A local man told Thaxton in 1990 that everyone was afraid of reporting the actual size of the harvest because it was seen as too small. “No one dared to resist [the false reporting] because at that moment there was an atmosphere of madness surrounding the government drive for grain collection.” Early in 1960 almost all of Da Fo’s grain was in commune storage, payments to villagers had been stopped, and “starvation loomed.” Even the blind were forced to stand in the fields, to “receive the energizing warmth of Chairman Mao’s radiant thought.”

One of the main ways the Party secured obedience throughout China, in addition to physical punishment, was public criticism. This was especially effective in a society that fears humiliation. Thaxton describes several varieties of shaming people: ostracizing those who declined to attend the public shaming events, condemning others who denied false accusations, and harshly treating those who had broken even minor regulations. These sessions became “the key instrument of Maoist terror, creating a climate of political hysteria, sycophancy, and aggression.” “I had to lie,” an informant told Thaxton in 1994. “Otherwise, I would be criticized…. We had to exaggerate production, but when we exaggerated the villagers had to suffer hunger.”

Thaxton provides an example of this form of terror and its immense consequences. Those accused of laziness were forced to wear a white ribbon, white being the Chinese color for death. If the head of a household wore one, an informant reported, “the family reputation was ruined.” In one family, from the Bao clan, the family head, accused of shirking and forced to wear the white ribbon, died of shame. Soon his wife, equally ashamed, died, as did their elder son. The younger son fled the village. The Party leaders ordered that the tombs of the three dead Baos be leveled, a “shocking act of cultural violence,” as a warning to the rest of the village. Everyone knew that the family line had been wiped out because it was known that surviving sons of such a family would never find wives: they were “understood as alien, undependable, unmarriageable.” That such a taboo would be effective with villagers who knew that the punishment had been purely political testified to a condition of mass fear that is still inadequately understood.

Advertisement

Da Fo’s population of just under 1,500 in the late 1950s was a speck in the Chinese famine of 1959–1961 in which 35 million to 50 million died, the worst such catastrophe of the twentieth century or perhaps ever. As Thaxton shows, under 10 percent of the village’s inhabitants died, a considerably smaller proportion than many other places where most or even almost all the inhabitants died.

Thaxton wanted to find out by what strategies so many villagers had survived, and he found they were numerous, sometimes age-old. Among them were footdragging, pretending to work hard but finding places to sleep during night labor; remittances of money from better-off relatives elsewhere; migration to other parts of China where there were rumors of more food or less brutal treatment; secret, illegal selling of salt on the black market; begging, either within the village or from relatives elsewhere; stealing crops, especially in late 1960 “when Da Fo’s inhabitants were so hungry that they felt as though each day was their last on earth”; and gleaning—picking up what was left after a harvest—of crops sometimes deliberately left in the fields. Rather than admitting that their subjects were dying of hunger, local Party leaders deemed all such acts sabotage or political opposition.

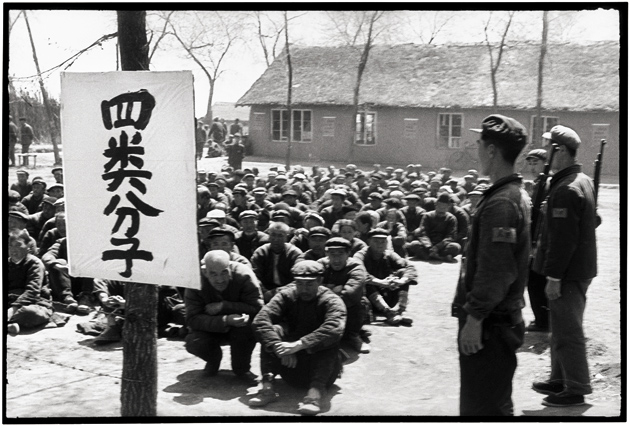

Li Zhensheng/Contact Press Images

Peasants kept under guard by local militia as they wait to be denounced at a mass rally, Liaodian commune, Acheng county, Heilongjiang province, May 13, 1965. The characters on the sign stand for the words ‘four elements,’ i.e., landlords, rich peasants, counterrevolutionaries, and ‘bad characters.’

Indeed, “talk about food was defined as political talk, it was neither tolerated nor forgiven by party leaders.” The famine and the dying could not be mentioned. In 1959 Mao had purged one of his closest comrades, Marshal Peng Dehuai, for reporting starvation in his own home region; from then on, writes Thaxton, cadres who failed to come up with the expected amount of grain were accused as “little Peng Dehuais.” In a once-prosperous prefecture, Xinyang, not far from Da Fo, one scholar cited by Thaxton estimates that well over two million people starved to death; during one period there was no food at all. A Da Fo Party leader with a conscience made an investigation in Xinyang and reported his findings to the provincial Party secretary, a liar and bully. The honest official was branded a rightist and expelled from the Party. “The Xinyang incident was not made public until 1982” but the villagers in Da Fo knew about it.

As a desperate last measure, which became a principal reason for their relatively low death rate, residents of Da Fo embarked on chi qing, eating unripe or immature grain, peanuts, corn, beans, and melons, before the harvest. A villager told Thaxton in 2001:

The reason very few people died of starvation in Da Fo…was that… everybody felt…they were entitled to eat the green crops from the public fields…. We did not really feel…we were stealing. We were taking our share of the green crops, a share that belonged to every one of us.

This strategy, however, could not save very young children from dying; only children over six were taken to the fields where they could eat the unripe crops. Even some local officials approved and participated. They were as hungry as everyone else. But the villagers recalled for Thaxton that top leaders like Bao Zhilong ate in their own “hush kitchens,” and stored food in their houses and in what should have been public granaries. By 1961 the peasants had eaten almost all the wheat harvest; this became a crisis in Henan province, which was receiving no revenues. Some peasants admitted to Thaxton that “eating the green crops was the best form of resistance.” He states:

The same villagers who were eating their way out of the Great Leap famine via chi qing were also eating away at the fiscal base of the central government.

Thaxton shows as well that the various forms of survival, especially chi qing, and eating sweet potatoes grown in tiny private plots, preceded what is usually given as the reason for a slow recovery in the countryside: the policies in 1961 of Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping that returned some land to the peasants. Da Fo’s local form of staying alive, he suggests, is why the peasants, who were intent on saving themselves, did not openly rebel.

For a few months in late 1961, as part of Beijing’s damage control operation when the famine became too severe to conceal, Bao Zhilong was detained for “education,” and even returned briefly to Da Fo to endure some public criticism from his victims. He accepted this stoically, and before long, to the dismay of the village, he was allowed to return to his previous post. But the Cultural Revolution brought serious, although still not permanent, retribution to Bao. Instead of what Mao intended—the smashing of his enemies and critics—in Da Fo and its district, local people openly voiced grievances “to publicly shame and secretly strike back at the key party bosses who had manufactured food shortages and made families suffer.”

What villagers did, in short, was to appropriate “a familiar instrument of Maoist politics: the public criticism session.” Bao was made to crouch on a stage and listen to condemnation, was struck by the rice bowls of famine survivors, and at a night meeting was beaten. Villagers threw manure at his doors, “an act that was considered an insult and a curse.” Absurdly, Bao was accused by an ex-accomplice, trying to save himself, of being “the number-one agent of the anti-Mao party faction.” Yet again, to the villagers’ horror, in 1973 Bao was returned to power. Thaxton writes that the effect of the lying, unpredictability, and, above all, lack of contrition “left Da Fo’s Communist Party vulnerable to the dangerous popular memory of suffering and loss in the Great Leap Forward Famine.”

Over the years—while some leaders looked away—Da Fo’s villagers gradually, sometimes secretly, returned to the private economy and resumed the traditional pastimes that had made them relatively happy in pre-Mao days. They resisted the grand Party lie, called yiku sitian —“remembering the bitter past and savoring the sweet present”—that sought to convince local people that whatever their sufferings, and these were minimized, it was the Party that had rescued them. Bao Zhilong himself “seemed to behave as if the famine had never happened, and he complied with all of the state campaigns to erase or alter the memory of the famine.” But everyone recalled people dying in snowy fields while gleaning turnips in the dark. They remembered, too, the dead who vanished or were improperly buried, whose ghosts wandered menacingly about.3 The memories never disappeared and decades after the famine waves of arson directed at Party bosses swept Da Fo. The villagers kept alive memories of top leaders like Bao Zhilong eating in their own private dining halls and storing food in their houses. In 1989 and again in 1991 Bao Zhilong’s house was burned down. What the villagers were saying, Thaxton powerfully surmises, decades after they had starved, was:

We have not forgotten your complicity in the Great Leap atrocity. We have not fallen for your revised narrative of how to remember the famine. We have been waiting for a chance to voice our anger, and now you will hear us.

But the survivors still bear the visible scars, as Thaxton himself saw on his many visits to Da Fo, of their beatings at the hands of Party bullies, as well as the invisible ones from decades of malnutrition. A constant diet of sweet potatoes left lasting intestinal damage. From 1961 on, the Party attempted to snuff out memories of the national disaster: in a Da Fo school a teacher informed students that the famine arose from natural causes. Many urban Chinese still believe that three years of bad weather as well as local bungling caused the famine and that Mao and the Party had kept things from being much worse.

Such false reassurances were doomed to fail. Thaxton is convinced that oral histories, derived from careful interviews, can persuade people who are afraid of one another and of local officials to tell their versions of the truth. His book is a triumph of scholarly patience over many years, and displays keen insight into what he was uncovering and meticulously piecing together. Eloquent in his presentation, he does not conclude more than the evidence shows. In Da Fo, as Thaxton writes near the end of his immensely readable micro-study with its enormous implications, the Party has never apologized. To do so, he says bluntly, “would have constituted an admission of an inconceivably monstrous abuse of state power.”

Thaxton evokes the years of arson by protesting peasants, the “volcanic blazes in the night sky, the anguished disbelief and hysterical cries of the haughty and dominant arson targets.” And he has seen the burned-out ruins, “material evidence of a story that villagers wanted to tell,” which he now masterfully relates on their behalf. Ralph Thaxton does well in his final passage to recall William Faulkner’s statement “The past is not dead. In fact, it’s not even past.”

I don’t know how many Da Fo villagers sent their young people to join the 113 million migrants from China’s villages to sweat in the factories of the south, producing the “Made in China” goods we buy these days. One factory alone made every famous brand of running shoe. If Da Fo’s young people were not traveling south they are unusual. For many years China’s villages were emptied of their young, as Leslie Chang, for ten years a reporter in Beijing for TheWall Street Journal, shows in Factory Girls. Despite what the book jacket claims, this is not the first such study. Alexandra Harney’s The China Price, 4 for example, covers much of that migration, and is stronger in its analysis of the price rural Chinese pay in lives and money. But Chang is a more vivid storyteller.

Factory Girls is a misleading title. There are two books here. One is indeed about the peasant girls who chuqu, “go out,” from their rural homes, abandoning most of their native culture for joyless urban lives devoted to making money and perhaps catching a husband. The stories of these young women are entertainingly and sometimes poignantly related, although Chang does not disguise how much she dislikes what she observes in rural China. According to the economist Yasheng Huang, the main reason for the escalation in rural migration to the cities is the regime’s policies in the 1990s, which impoverished the countryside.5

Now we read that the southern factories that attracted the girls Chang writes about are closing. With the international credit crunch, 14,000 Dongguan factories have closed down this year, including 3,900 toy factories, or half the total. There seems to be a general collapse of the southern export economy, partly because of the drop in American imports from China. It is officially estimated that well over six million migrant workers will soon be out of work. From almost 12 percent per year, this year’s economic growth has sunk to 9 percent. The World Bank has just estimated that it will fall to 7.5 percent next year. But there is also a global fear that some Chinese products, such as toys, are contaminated with lead, and other goods are also contaminated, including pet food, toothpaste, and, perhaps worst of all, powdered milk to which the chemical melamine has been added to make the milk feel thicker and to give it a higher protein content. Such powdered milk has already poisoned almost 400,000 Chinese children, according to the Chinese authorities, and killed at least four. Chang could not have seen this coming, although Yasheng Huang predicted such a collapse in his recently published book.

In the other part of her book, Chang, who was born in America, writes about her own family, tracing its past in China and examining her own feelings about it. This part is less interesting, since Chang is far less close to her remaining relatives than to the factory girls she came to know. She put off meeting her scattered family in China for years and she fails to face or grasp fully what happened to them under Maoist rule. She learns that her father’s cousin doggedly continues to demand a state apology for the persecution of his father during the Maoist years. He seems heroic in doing so. But when he tells her that his already long-written account has stalled at the 1957 Great Leap, she suddenly feels “very tired.” That was two years before the greatest disaster in twentieth-century China, so exhaustively explored by Ralph Thaxton, which most of her relatives would prefer to “forget.” Chang comes across as an expert and empathetic contemporary observer, with little interest in analysis of past attitudes.

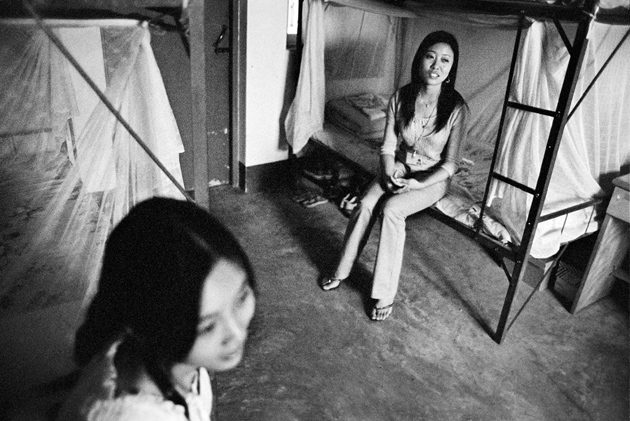

Chang likes Dongguan, with its six, seven, or ten million—no one knows how many—inhabitants. She says she likes the gangsterish men who fondle the teenage prostitutes whom she flatly observes have chosen their trade, and most of all she likes the two young women whom she meets first in 2004; every couple of weeks for two years she travels to Dongguan, where they live. She stays and eats with them, visits their rural families, and meets the boys who court them. The girls constantly pursue and discard their suitors—while also changing friends, clothes, and hairstyles. Chang notices the way the girls tell lies, give and accept bribes, and search for Dale Carnegie–like secrets of success. The girls and their friends imagine that the path to wealth and happiness lies in knowing English, which some of them study ten hours daily, memorizing streams of words and sentences, and shaving their heads to exhibit nunlike devotion. I lost count of how many times they tried to change their identities. From recent reports it appears that their new lives are threatened or may be over. What will they do now?

This Issue

February 26, 2009

-

1

Edward Friedman, Paul G. Pickowicz, and Mark Selden, Chinese Village, Socialist State (Yale University Press, 1991), reviewed in these pages March 25, 1993; Revolution, Resistance and Reform in Village China (Yale University Press, 2005), reviewed in these pages May 11, 2006. ↩

-

2

For a detailed description of the plight of contemporary peasant life immediately east of Henan, see Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao, Will the Boat Sink the Water? The Life of China’s Peasants, translated by Zhu Hong (Public-Affairs, 2006); Unlike Thaxton’s book, this book does not show how decades of suffering led to the present rural crisis. See also Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State by Yasheng Huang, a professor at MIT (Cambridge University Press, 2008). Huang’s theme, described with great power, is the impoverishment of the countryside by the government after 1990. ↩

-

3

The same phenomenon of wandering ghosts, killed this time in the war, ravaged many Vietnamese in places like My Lai. See my recent review of Heonik Kwon, Ghosts of War in Vietnam (Cambridge University Press, 2008) in these pages, November 20, 2008. ↩

-

4

The China Price: The True Cost of Chinese Competitive Advantage (Penguin, 2008). ↩

-

5

Yasheng Huang, Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics, pp. 65, 124. ↩