To the Editors:

Any impartial reader of Richard Dorment’s essay [“What Is an Andy Warhol?” NYR, October 22] will easily come to the conclusion that Mr. Dorment has a particular point of view to advocate and has put forth this article in a thinly veiled effort to further his unstated agenda. Purporting to review three books on Andy Warhol, Mr. Dorment largely parrots the allegations made in Joe Simon’s lawsuit. In doing so, Mr. Dorment omits any mention of facts that contradict his opinion, and compounds this selective presentation of the facts with highly personal attacks on the professional competency of respected art experts—two dubious distinctions for a “book review” in a respected journal.

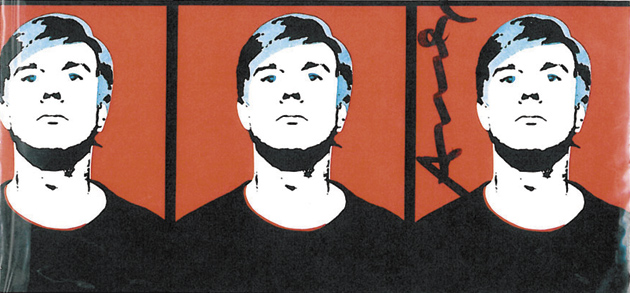

Mr. Dorment twice misstates the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board’s reasons for its opinion that Joe Simon’s 1965 self-portrait painting was not a work by Andy Warhol (“because Warhol was not present when they were printed”), and then goes on to quote a single sentence from the last paragraph of a letter the authentication board wrote to Mr. Simon. As Mr. Dorment knows, the preceding seven paragraphs of the letter set forth in detail the board’s reasons for its opinion, none of which have anything to do with Warhol’s presence during the creation of the painting.

Mr. Dorment also makes an ad hominem and petty attack on the professional credentials and scholarly independence of members of the authentication board, not by examining their credentials or actual decision-making independence, but, for example, by dismissing noted scholar and Warhol expert Neil Printz as a “teacher…in New Jersey.”

Mr. Dorment’s essay is a highly partisan attack on a charitable entity whose principal activity is making significant grants to worthy nonprofit arts organizations. Though thinly veiled as a book review, it is full of errors, omissions, and half-truths, which is not up to your editorial standards and violates the trust your readers have in you. Before forming a view, we hope that impartial readers will await the actual outcome of the lawsuit, as to which the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts expects to be fully vindicated against the utterly false claims made by Mr. Simon.

Joel Wachs

President Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts New York City

To the Editors:

As my name is mentioned in Richard Dorment’s article on Andy Warhol, I would like to add the historical significance to the issue discussed, namely the provenance of the silk-screen self-portraits in dispute. The Warhol silk-screen self-portraits resulted from a collaboration I undertook with Warhol (who personally gave me the silk-screen separations with instructions for printing), which in turn resulted in the first documented public showing of video art by a recognized artist. This event is recorded by author, curator, and historian Michael Rush in his definitive book Video Art (Thames and Hudson, second edition, 2007). One could fairly state that this event marked the earliest public awareness of this medium, enabling scholars to proclaim Warhol the “father” of video art. With this recognition, the contributions of Warhol to art history loom larger than ever.

Richard Ekstract

New York City

To the Editors:

After reading Richard Dorment’s recent review, which highlighted Joe Simon’s struggles to get his painting authenticated, all I could do was walk away thinking: How many millions of dollars would the charitable Warhol Foundation save in legal fees if they simply worked out their differences with Simon? Going a step further, why not set up a panel of known Warhol scholars and art historians and let them settle it?

As someone who was part of the provenance of the Warhol self-portrait in question, as well as an art dealer and writer who is quite familiar with Warhol’s working methods, I can vouch for the fact that it is all about artist’s intent. And Warhol not only gave permission for Simon’s painting to be created, he turned over the acetates for it to be printed. That’s what I call intent!

Richard Polsky

Sausalito, California

To the Editors:

My family owns one of the ten silk-screen self-portraits of Andy Warhol that the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board is conspiring to remove from Warhol’s oeuvre and the art market. Despite not ever putting the picture up for sale or having any contact with the authentication board at all, we were surprised to receive a letter from the board in the spring of 2004 inviting us to submit our picture for authentication. Only persistent questioning of the board’s intentions saved our picture from being defaced with a denied stamp because its seemingly straightforward letter was ultimately exposed to be a premeditated and underhanded ploy to deauthenticate our picture.

Whether the authentication board and Warhol Foundation are truly trying to control the market in Warhol’s works we won’t know until the completion of the discovery process and pending class-action lawsuit. It is about time, however, that somebody strips off the cloak of secrecy that surrounds the board’s intentions and decision-making.

Advertisement

Richard Dorment’s article is a start in that it exposes a board seemingly more interested in protecting its skin than in honoring the artist’s last wishes and advancing the scholarship of his work. With so much of Warhol’s fortune being diverted away from charitable causes to fund an expensive legal team defending self-inflicted lawsuits, one can only wonder what Warhol himself would make of such profligacy.

David Mearns

West Sussex, England

Richard Dorment replies:

I am appalled that Joel Wachs thinks my purpose in writing about the Andy Warhol authentication board is “thinly veiled.” I’d hoped it was clear as daylight. At least he noticed that the article was not in essence a book review but an attack on the authentication board’s competency. And yes, it was indeed “highly partisan.”

The seven paragraphs preceding the line I quoted from the board’s letter rejecting one of the pictures in the series (now owned by d’Offay, by the way, not Simon-Whelan) concern the significant differences between two series of Warhol self-portraits, the first of which (1964) the board considers genuine, the second (1965) not. Not only are these differences fully acknowledged in my article, but I specifically mention most of them: linen vs. cotton duck, different background colors vs. uniform red, evidence of the artist’s hand in the paint texture vs. a flat mechanical-looking surface.

Of course I was summarizing, but for Mr. Wachs’s benefit I can go into more detail here. Observing that the halftones in the second series are less dense than those in the first, the letter to which Wachs refers concludes that the pictures in the second series were not made from the same silk screen that Warhol used to make the first. But of course they weren’t: as I explained, the second series was made not from the original silk screen, but from the acetates—transparencies—that Warhol gave to Richard Ekstract, who in turn took them to a factory where they were used to make the silk screens from which the pictures in the second series were printed. That the authentication board has failed to grasp these basic facts merely reveals how little it has understood—or tried to understand—the sequence of events that led to the creation of the second series.

But every objection raised by the board came down to the same issue—the first series was made by hand, the second mechanically. If Mr. Wachs really thinks that none of this has “anything to do with Warhol’s presence during the creation of the painting,” as he writes, he is profoundly mistaken.

Mr. Wachs takes me to task for querying the professional credentials of Ms. King-Nero and Mr. Printz, but as president of the Andy Warhol Foundation, he of all people should be concerned that so many cases have arisen in which doubt has been cast on the board’s research methods and conclusions. Warhol is one of the most important artists of the twentieth century. Instead of rejecting out of hand the arguments of those who want to see the board called to account, has it not occurred to him to listen to the growing chorus of disquiet?

Readers should not be fooled by Mr. Wachs’s bluster. His complaints are a diversionary tactic intended to shift attention away from the sublime idiocy of his board’s closing sentence in its letter: “It is the opinion of the authentication board that said work is NOT the work of Andy Warhol, but that said work was signed, dedicated, and dated by him.”

I challenge Mr. Wachs to tell us, in these pages, how this is possible. How can such a picture—and moreover a picture that the artist personally approved for inclusion in his first catalogue raisonée, and approved its being reproduced on the catalogue’s cover—not be by him? If he can answer the question cogently, I’ll withdraw my words. If he can’t, his position is indefensible. He will then be personally responsible for wasting millions of dollars—attempting to shore up the credibility of his scandal-ridden board—that the foundation could otherwise have spent on its charitable activities, and should resign.

This Issue

November 19, 2009