The weather cooperated with Glenn Beck on the August morning of his “Restoring Honor” rally. Or maybe it was a higher force. The skies were clear, it was hot but not Washington unbearable, and the crowd, prepared with lounge chairs and water bottles, was serene. He had also banned signs from the event so that he and his fans would not be easy targets for photojournalists, which was a canny way to introduce a kinder, gentler Beck.

He had been a busy man, publishing in June his dystopian thriller, The Overton Window, which has been selling briskly. In July he founded Beck University, a noncredit online education program that offers potted lectures on religion, American history, and economics. In August he was busy setting up his own Huffington Post–style website, called The Blaze. And now here he was, standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, looking out on a crowd of about 87,000 followers who had traversed the country in self-organized bus caravans just to listen to him. He did not rant, he did not rave. He did not, as I recall, mention Barack Obama or call anyone a “socialist” or even a “progressive.” Instead he talked about God and family, about repenting from our sins (including his own), about expressing hope rather than hate, serving others and our country, and tithing to our churches. He prayed, the clergy standing with him prayed, and his followers prayed, arms upraised, waving gently to the beat of some inner hymn.

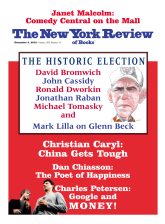

Beck is the most gifted demagogue America has produced since Father Coughlin made his populist broadcasts during the Great Depression. In the course of one radio or television show he can transform himself from conspiracy nut and character assassin into bawling, repentant screw-up, then back to gold-hoarding Jeremiah, and finally to man of God, without ever falling out of character. Which is the real Glenn Beck? His detractors assume that his basest, most despicable moments reflect his core, and that the rest is acting and cynical manipulation.

This is Alexander Zaitchik’s conclusion, in his sharp and informative smackdown, Common Nonsense, and Dana Milbank’s in his rambling, impressionistic Tears of a Clown. Zaitchik documents Beck’s every flip-flop, every swim in the polluted pools of the John Birchers and paranoid Mormon theocrats, every cruel remark (he called Hurricane Katrina victims “scumbags”), and every offensive comparison (he once likened Al Gore’s campaign against global warming to Hitler’s persecution of the Jews). For Zaitchik, Beck is just one more American con artist in the P.T. Barnum tradition, a shameless pseudoconservative bottom-feeder who will say anything to keep the spotlight on himself while the money rolls in.1

But after reading these books and countless articles on the man, I’m coming to the conclusion that searching for the “real” Glenn Beck makes no sense. The truth is, demagogues don’t have cores. They are mediums, channeling currents of public passion and opinion that they anticipate, amplify, and guide, but do not create; the less resistance they offer, the more successful they are. This nonresistance is what distinguishes Beck from his confreres in the conservative media establishment, who have created more sharply etched characters for themselves. Rush Limbaugh plays the loud, steamrolling uncle you avoid at Thanksgiving. Bill O’Reilly is the angry guy haranguing the bartender. Sean Hannity is the football captain in a letter sweater, asking you to repeat everything, slowly. But with Glenn Beck you never know what you’ll get. He is a perpetual work in progress, a billboard offering YOUR MESSAGE HERE.

As anyone who witnessed his performance on the Washington Mall can attest, what makes him particularly appealing to his audience is not his positions, it is that he appears to feel and fear and admire and instinctively believe what his listeners do, even when their feelings, fears, esteem, and beliefs are changing or self-contradictory. This is the gift of the true demagogue, to successfully identify his own self, rather than his opinions, with the selves of his followers—and to equate both with the “true” nation.

To understand someone like Beck, and the people who love him, you need to stay on the surface, not plumb the depths or peek behind the curtain. He is an ambitious man who wants power and will say anything to acquire it. But over the past year or so he has simultaneously been crafting an alter ego who appears more thoughtful and forward-looking, decked out in professorial glasses and sometimes a pipe. His books and televised lectures, mainly on American history and religion, also have a clearer focus. By the looks of it Beck is trying to sketch out some kind of prophetic vision for his Tea Party followers, linking the libertarian politics they say they want to the individual spiritual transformation he now says they need. Coming from someone who used to call himself a “rodeo clown,” and still lives up to the billing, this is pretty astonishing. But given his success so far in sensing what a certain American public is feeling, it merits attention. It may mean that the Tea Party sympathizers who adore him want more than to be left alone, they want someone to lead them out of Egypt.

Advertisement

And here comes Moses.

The night before the “Restoring Honor” rally Beck held an event called “Divine Destiny” at the Kennedy Center for a mainly handpicked audience of ministers and churchgoers. The idea was to run his new ideas before a couple of thousand sympathetic souls before stepping out on the Mall the next day. On both occasions he said very little about the present. Instead, he told the story “they” won’t tell you, about how America was founded by men of faith who believed in God as the divine source of individual rights, and considered church and family, not politics, as the twin centers of national life. Beck echoed many of the ideas found in Willard Cleon Skousen’s Mormon political catechism, The Five Thousand Year Leap, and in the dubious historical research of David Barton, an influential, self-taught evangelical minister who was on stage with Beck during the event. But when Barton, who runs a Christian nationalist organization called WallBuilders, repeated his group’s dogma that “most of our presidents and founding fathers thought of this as a Christian nation,” Beck objected, took the mike, and stated flatly that “one thing that cannot happen: religion and politics must not mix…. That’s what happened in the Weimar Republic.” Barton backed off.

It was a revealing moment. In Beck’s budding political theology, ours is a godly nation but not a narrowly Christian one. The Lord lays out basic principles of individual rights and points out a moral “true north,” but that’s pretty much it. America has flourished whenever it has recognized His role, publicly and privately, but has strayed whenever it claimed a monopoly on those principles for one faith, or twisted them for some mundane purpose. On this score, he pointed out that night, “America has been very good, and very bad,” its history pockmarked by terrible sins committed with religion’s blessing: slavery, the slaughter of Native Americans, the persecution of Mormons, and, surprisingly, imperialism. (“Manifest Destiny,” he told his television viewers the week before, “is a perversion of Divine Providence.” )

The next day, as if to remind us of our national wrongs, he surrounded himself on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with an enormous poster of a Native American warrior, another of Frederick Douglass, and one of what seemed to be a Mormon pioneer family heading west in its covered wagon. He also projected a video montage of images from the civil rights movement, invoking Martin Luther King Jr. whenever possible, and stressing, correctly, that King was a minister standing up for divinely bestowed human rights, not a secular activist. It was political theater of the highest order. And it was fresh. It’s impossible to imagine Jerry Falwell or Pat Robertson or James Dobson sharing the stage with Frederick Douglass.

Beck skipped over the next part of his pitch, which he recounts in hair-raising language on his daily shows, and which his listeners know by heart—how, around the beginning of the twentieth century, power-hungry elites convinced “ordinary” Americans to abandon the Founders’ principles in the name of progressivism, eroding our rights in a steady process that has culminated in Barack Obama’s socialism. This loopy story would have ruined the atmosphere Beck was trying to create. Instead, he placed some blame on ordinary Americans themselves, who, he said, have grown spoiled and indifferent to their own liberty. This has become a new theme in his books, as well. As he put it in his best seller Common Sense, which was published just after the first Tea Party demonstrations:

Americans have changed. Our parents and grandparents relied on debt only to buy a home or a car or put someone through college, but we rely on it to live the lives we think we have earned…. Suddenly, our summer vacations, flat-screen televisions, boats, clothes, and dinners out at fancy restaurants were all “purchased” with debt…. If we didn’t have the money, we acted like we did. We felt like we deserved to have it all—big homes, big cars, big TVs.

Abandoning the grab-it-all gospel preached by the Republican Party since the Reagan years, Beck chastises Americans for becoming a people who have forgotten that “capitalism isn’t about money, it’s about freedom.” In his sermon at the Kennedy Center, he proclaimed that America doesn’t need “change we can believe in,” it needs to be restored to its original principles. But that can only happen if individual Americans recover their private virtues and again place God, however they conceive Him, at the center of their lives. His congregation went wild.

Advertisement

There are other ways, too, that Beck has departed from Republican orthodoxies. His libertarian political theology not only takes a dim view of economic self-indulgence and debt, individual and national; it is hostile to expansionist foreign policies, the influence of Wall Street, and what he sees as a growing national security state. From Common Sense again:

Under President Bush, politics and global corporations dictated much of our economic and border policy. Nation building and internationalism also played a huge role in our move away from the founding principles…. Through legitimate “emergencies” involving war, terror, and economic crises, politicians on both sides have gathered illegitimate new powers—playing on our fears and desire for security and economic stability—at the expense of our freedoms.

At the start of the recent Iraq war, Beck was everywhere, “rallying for America” in a flag shirt and telling anyone who would listen, “I am so grateful to God in heaven that George W. Bush is our president.” This past year, sensing a shift in public opinion, he’s been test-driving some fairly isolationist ideas, and in April he made the following confession:

In the last five years, I have—I’ve gone from a big hawk to not Ron Paul, but on the road to Ron Paul…. Honestly…, I wasn’t paying attention before 9/11. I didn’t know what the heck was going on in the world. Now, I’m paying attention. When people said they hate us, well, did we deserve 9/11? No. But were we minding our business? No. Were we in bed with dictators and abandoned our values and principles? Yes. That causes problems…. I’m not going to screw with the rest of the world. I’m going to get out.

In his didactic thriller The Overton Window he is even more explicit and offers a surprising take on post–September 11 America. The book’s conceit is that behind the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks was a conspiratorial network of business, finance, and political leaders working with foreign governments and international organizations to establish a post-democratic world order ruled by elites. Their long-term strategy was to gradually undermine American sovereignty by promoting globalization, establishing an autonomous military-intelligence-police apparatus by exaggerating security threats, and nudging the world economy toward ruin by running up national debt. The basic idea was to bring democratic governments everywhere to the point of collapse and then create a state of emergency allowing the New World Order to emerge. That was what the attacks were supposed to accomplish but didn’t. Now it’s time for another try.

The cabal’s mastermind is Arthur Isaiah Gardner, an elusive public relations executive with a genius for manufacturing market demand and political consent, whether for bottled water or the Gulf War. He secretly directed the campaigns of all our recent presidents except Jimmy Carter (too holy) and Richard Nixon (too cheap). Gardner is also a would-be messiah who thinks he’s been called to redeem humanity. He once believed in America and its democratic promise, but at a certain point had to accept the evidence of his eyes. The truth must be faced: the American experiment has failed and the time has come for the rule “not of the people this time, but of the right people: the competent, the wise, and the strong.”

The Overton Window is a kind of inverted Ayn Rand novel. While she romanticizes the lone atheist visionary struggling against the conformist herd, Beck idealizes the common folk who resist the John Galts and Howard Roarks of the world. The evil Arthur Gardner is up against the flannel-shirted members of a Tea Party–like organization called the “Founders Keepers,” a Web-connected crew of God-fearing populists devoted to the Constitution and small government, who have vowed to resist the tyranny of the “self-appointed ruling class” of “huge corporations, international banks, the power brokers on Wall Street, foreign governments, media giants” who are creating “a two-class society in which the elites rule and all below them are all the same: homogenized, subordinate, indebted, and powerless.”

On a lark, Gardner’s son Noah (yes, Noah) attends one of their meetings, which is broken up by Blackwater-type goons and agents provocateurs pretending to be gun nuts and anti-Semites. So he begins collaborating with the Keepers to help foil his father’s plot, which they only partially do. Noah is captured and taken to a secret prison where he is beaten, waterboarded, and given electroshock in hopes of drawing him back to the dark side. As the novel ends he is in a halfway house being rewired for future use, though maintaining secret contacts with the Keeper underground. A sequel is promised.

No one picking up a Glenn Beck thriller will be surprised to find Congress demonized, along with the IRS, the United Nations, and the Council on Foreign Relations. But the libertarian Beck also puts into the mouths of his characters a litany of left-wing complaints and conspiracy theories of a libertarian tinge. Besides the usual government crimes that haunt the right-wing imagination, characters in The Overton Window also denounce presidential national security directives, spying on domestic dissenters, the privatization of the police and military, the preventative detention and torture of potential terrorists, undeclared wars, the internment of Japanese-Americans, the overthrow of Latin American governments, the disproportionate incarceration of young black men, corporate campaign contributions, and the bailout of Wall Street millionaires.

Oliver Stone, you’ve got mail. Dick Cheney, you don’t.

Beck has been the lead horseman of the American Apocalypse for some time. But now he seems to be catching on to the fact that despite our susceptibility to conspiracy theories, Americans can’t be mobilized for long by fear alone. We just don’t do Kulturpessimismus. We do divine providence, five-point plans, miraculous touchdowns as the clock runs out, and the whole town coming together to save the bank because, gosh darn it, it’s a wonderful life. So after a few years scaring the wits out of us, Glenn Beck now wants to reassure us that God has a plan for us. A couple of days after the Washington rally he told his television audience, “I know you and I have a special relationship and that you trust me, and I value that trust…. I recognize that I am in this place at this time for a reason…. What God is telling us is ‘get behind Him.'” At the rally he coyly dropped that “God gives me hints of stuff,” though he doesn’t always understand everything He says. “I’m not the smarter one of your children,” he joked, “you’ve got to be more clear. Speak slowly.”

Originally the rally was promoted as the public unveiling of a book Beck kept calling “The Plan.” As the date neared, and perhaps as the book got delayed, or God was dictating too fast, the rally was refocused on larger themes. The book is now finally with us, under the title Broke: The Plan to Restore Our Trust, Truth and Treasure, and it is a strange piece of work—sober, even boring, and totally unlike his sly, satirical best sellers Arguing With Idiots and An Inconvenient Book. It’s all about our growing national debt and seems to have been outsourced to think-tank types who wrote wonky chapters about such arcana as the distinction between “unified cash basis” and “modified accrual basis” budget accounting. It is a fairly standard libertarian tract, offering the same analysis and proposals one finds in reports from the Heritage Foundation or the Cato Institute, or in articles in Reason magazine, which are all cited frequently here. There is a call for minimal government, more federalism, a flat tax, balanced budget and term-limit amendments, stemming the growth of Social Security and Medicare payments, and serious cuts in defense spending.2 The book offers a surprisingly coherent, though wholly fantastical, picture of America’s future. But like all twelve-step programs, it is aspirational, not realistic.

Far more interesting, and potentially more consequential, was the “plan” Beck presented in his Washington gathering: his call for a “third Great Awakening,” a national conversion back to divine principles. “God is not done with you yet, and he is not done with man’s freedom yet.” Just read the two words carved into the Washington Monument and let them sink in: LAUS DEO, praise be to God. If we can do that again, in word and deed, we will see “the beginning of the end of darkness,” we will restore our nation, we will “restore the world.” But remember that if we try to change Washington without changing ourselves, we will fail. “America is great because America is good,” he declared, but

we as individuals must be good so America can be great…. God is not on our side; we have to put our lives in shape so we will be on God’s side…. Go to your churches, your synagogues, your mosques, go to those who are teaching the lasting principles.

He encouraged them to pray often, leaving the door slightly ajar so their children could learn from the example. He also urged them to tithe to their places of worship and to be as generous as possible in giving to private charities. Good to his word, Beck used the rally to raise money for the Special Operations Warrior Foundation, which provides scholarships for the children of slain soldiers.

Watching a tape of the rally later, I was struck by how artfully he touched on themes dear to the religious right—family, church, honor—without sounding angry or exclusionary. This, too, seems in keeping with the laissez-faire doctrines of the Tea Party movement, which has ruffled the feathers of some old-school evangelical activists. As one of them recently said, “there’s a libertarian streak in the Tea Party movement that concerns me as a cultural conservative. [It] needs to insist that candidates believe in the sanctity of life and the sanctity of marriage.”3 Beck refuses to do that. He has even gone on record saying he sees no threat to the family in gay marriage.4

Instead he is doing his own mobilizing, on his own terms. Last year Beck formed something called the “9.12 Project,” whose mission, according to its website, is to “bring us all back to the place we were on September 12, 2001.” It asks members to affirm a charter of the “9 Principles” and the “12 Values.” The principles are a mix of the patriotic (“America Is Good”), the religious (“I believe in God and He is the Center of my life”), and the moral (“I must always try to be a more honest person than I was yesterday”). Politically, they are down-the-line libertarian: “The government works for me.” The values to be respected in private, on the other hand, are softer and more generous, like reverence, hope, thrift, humility, gratitude, and charity. Beck is no longer directly involved with the project but it served its purpose, which was to show that his developing vision could mobilize like-minded Tea Party types under his own banner. His message is simple: America can be saved if it turns and follows Him. And him.

Tune in to one of Beck’s shows today and you’ll see that he remains the coincidentia oppositorum he’s always been—angry, thoughtful, ironic, nasty, sentimental, bathetic. His new Moses character is just one more in his dramatic repertoire and who knows how long he will choose to play it. I suppose it all depends on the reviews from the Tea Party faithful. Polls show he is the most popular public figure among movement sympathizers, running just ahead of Sarah Palin, though his message is not the same as hers. He presents himself as a social libertarian, not a social conservative, he is isolationist in foreign policy and skeptical of the national security establishment, and he wants to end Social Security as we know it. On paper, at least, that puts him at odds with a large segment of the Tea Party’s supporters. Yet they revere him and believe he understands them.

This is not as puzzling as it seems. Beck’s libertarianism is a more developed and consistent reflection of the Tea Party’s own highly individualistic political rhetoric. But as some thoughtful conservative commentators have noted, those who identify with it also believe that American society, not just the government, has gone off the rails, that families are weaker, people less honest, less respectful, less good—that, as the pollsters put it, “the country is headed in the wrong direction.” But what these same commentators fail to appreciate is that the social developments that the movement’s sympathizers worry about are consequences of the very same individualism the Tea Party says it wants to advance. As I’ve suggested in these pages before, the Tea Party movement is yet another expression of a libertarian urge that has reshaped American politics and civil society over the past half-century.5

But it also expresses the disquiet of people unhappy about the more atomized and anarchic world they now find themselves in. Tocqueville would have understood this. One of the lessons of Democracy in America is that the prospect of absolute freedom is terrifying, the world it delivers lonely and hard. The freer a nation becomes, Tocqueville conjectured, the more people feel they are on their own and must create themselves, the less willing they and their fellow citizens are to accept authority and traditional obligations, then the more they will crave a connection to each other and to the Beyond.

Similar dynamics may help explain why Glenn Beck, sensing an opportunity, has moved into the prophet business, and why his adoring fans on the Washington Mall were so happy to be chastised and told they must transform themselves within if they wanted their country transformed. Beck is often likened to Elmer Gantry or to Lonesome Rhodes in Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd, and he is certainly capable of playing those roles. But coming back from his rally I was reminded of a different movie, Frank Capra’s 1941 classic Meet John Doe. In that film, Barbara Stanwyck plays a reporter losing her job during the Depression. As a final protest against her ruthless, Murdoch-like publisher (Edward Arnold), she slips into the paper a letter from a fictional “John Doe,” who laments his poverty and threatens suicide. The letter strikes a chord with readers and everyone wants to meet and help John—who doesn’t exist. Scrambling, Stanwyck holds tryouts for the part and settles on Gary Cooper, an unemployed baseball pitcher, and writes a public speech for him.

It was not just the obvious parallels with the present moment that brought the movie to mind, it was the speech Gary Cooper delivers. What makes it so successful is that it betrays no anger, only hope and love. It doesn’t demand government action to help America’s John Does, nor does it attack government as the source of their problems. Instead, it simply calls America to look within and discover its old, better self. When he begins, Cooper is only reading the lines in an awkward, half-bored manner. Halfway through, though, something dawns on him and his delivery becomes inspired; he starts believing the words coming out of his mouth, as does the audience. By the end he is thundering and the crowd is cheering:

Now, why can’t that spirit, that same warm Christmas spirit last the whole year round? Gosh, if it ever did, if each and every John Doe would make that spirit last three hundred and sixty-five days out of the year, we’d develop such a strength, we’d create such a tidal wave of good will, that no human force could stand against it. Yes, sir, my friends, the meek can only inherit the earth when the John Does start loving their neighbors. You’d better start right now. Don’t wait till the game is called on account of darkness! Wake up, John Doe! You’re the hope of the world!

The speech is a smash hit, so much so that the publisher conceives the idea—foiled when Cooper realizes what is happening—of creating and funding John Doe Clubs. Why? To create a populist third-party movement that he and his business associates can manipulate to put him in the White House.

This Issue

December 9, 2010

-

1

Readers can also consult the website of Media Matters for America (www.mediamatters.org), which keeps an updated catalog of his ludicrous claims and pronouncements. ↩

-

2

On foreign policy the book also lays out a Beck Doctrine, which holds that “we mind our own business,” “the enemy of my enemy is not my friend,” and “we sacrifice our values at our own peril.” (“Yes, Saudi Arabia, I’m talking to you.”) Worth noting, too, is that among the books Beck recommends to his readers is Andrew Bacevich’s impassioned work, The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced by War (Oxford University Press, 2005). ↩

-

3

See Ben Smith, “Tea Parties Stir Evangelicals’ Fears,” Politico, March 12, 2010. ↩

-

4

When challenged on The O’Reilly Factor in August, Beck reiterated his libertarian credo that “if it neither breaks my leg nor picks my pocket, what difference is it to me?” When O’Reilly insisted that gay marriage was a menace, Beck mugged a frightened face, stared into the camera, and asked, “Will the gays come and get us?” ↩

-

5

See my “The Tea Party Jacobins,” The New York Review, May 27, 2010. ↩