In response to:

What Is a Warhol?: An Exchange from the December 17, 2009 issue

To the Editors:

“This may be the first time in history,” Richard Dorment writes in “What Is an Andy Warhol?” [NYR, October 22, 2009], “that a signed, dated, and dedicated painting personally approved by an artist…has been removed from his oeuvre by those he did not personally appoint.” The artist is Andy Warhol, and the painting in question is one from a series created in the mid-1960s entitled Red Self Portraits. Signed and dated in 1969 by Warhol and dedicated to his longtime European dealer Bruno Bischofberger, the painting was submitted in 2003 by a subsequent owner to the Andy Warhol Authentication Board, an offshoot of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, only to have it deemed a fake. “It is the opinion of the authentication board,” they wrote, “that said work is NOT the work of Andy Warhol, but that said work was signed, dedicated, and dated by him.” A gesture Orwellian in its absurdity, Dorment describes it as “farce.” That would be true, if there was not such an unsettling sadness to it.

When I read that passage, I could not help but recall my own encounters with the absurdity of the Warhol Foundation. For years following Warhol’s death, I covered developments surrounding his estate and foundation for various magazines, a prelude to my publishing the book Death and Disaster: The Rise of the Warhol Empire and the Race for Andy’s Millions (1994). One event I covered at length was the trial that took place in Surrogate’s Court that saw Edward W. Hayes, a former attorney for the Warhol estate, arguing for a realistic valuation of the Warhol art Warhol himself owned at the time of his death, that art—4,118 paintings, sculptures, and collaborations, 5,103 drawings, 66,000 photographs—being the bulk of his estate. Hayes believed the art was worth $708 million. But day after day lawyers for the Warhol Foundation appeared before Judge Eve Preminger arguing that Warhol’s art was worth drastically less—$95 million. Ultimately, Preminger split the difference, settling on $391 million. In retrospect, based on prices Warhol’s work is currently commanding, even Hayes’s high estimation seems painfully modest. The actual value of the Warhol art may have been several billion dollars.

But here’s the point. Lawyers paid for by Warhol’s own foundation happily arrived in court to denigrate Warhol’s work, even claiming at one point that investing in Warhol could be “risky,” to lower the value of the estate. Why? Since the foundation was required by law to give away 5 percent of the estate’s value, it wanted that value to be as small as possible, thus reducing the amount it had to contribute to charity. It was disturbing to watch the Warhol lawyers bash the Warhol oeuvre time and again. The act was hostile, perverse. I recognized the same kind of perversity in the authentication board’s letter to d’Offay.

Then, weeks later, I read in an exchange of letters in the December 17, 2009, New York Review of Books one way that Joel Wachs, the president of the Warhol Foundation, chose to respond to Dorment’s article. Wachs showed up at the offices of The New York Review of Books “to personally deliver material,” Dorment wrote, “to my editors that he believed would serve to discredit me.” (It didn’t.) Another memory flash for me. In March 1994, I published an article in ARTnews entitled “Let Us Now Appraise Andy Warhol.” It documented, at great length, the strangeness that was the Hayes trial. How did the Warhol Foundation respond? Archibald Gillies, then the foundation president, demanded a meeting in the office of the magazine’s editor, a meeting I attended, and when he showed up he spent most of his time attempting to discredit me as a journalist. He had brought with him a list of some one hundred “factual errors” in my article—as if I could have slipped that many errors past the magazine’s excellent fact-checking department—but when we looked at the so-called errors none seemed to be actual errors. None. The whole episode was merely an attempt by the Warhol Foundation to intimidate me.

I should not have been surprised. One of the first motions the foundation made during the Hayes trial was to close large portions of it to the public. When Preminger denied the motion, the foundation lawyers appealed that ruling to a higher court. There, the deciding judge was heard to say as he made his ruling, “Well, we usually keep these things open.”

But that’s just it. For years now, the Warhol Foundation has operated in secrecy, taking any means necessary to keep what they do private. What they have done over the years is sell off that vast collection of Warhol art contained in his estate, work whose value they did all they could to disparage, for an absolute fortune. Richard Dorment dared make public a mere handful of digressions carried out by the foundation as they have conducted their extremely lucrative business, and for that he was attacked. I’ve seen this before. It happened to me.

Advertisement

And no one from the foundation has yet to give a reason why the authentication board denied the authenticity of a painting Warhol himself signed, dated, and dedicated. Instead of trying to bully a journalist, why don’t they answer the key question that journalist has raised? My suspicion is, they are not answering the question because they can’t.

Paul Alexander

New York City

To the Editors:

Following is the response of the Andy Warhol Foundation to David Mearns’s letter [NYR, November 19, 2009].

Mr. Mearns’s allegation that the Andy Warhol Authentication Board somehow “conspired” with the Andy Warhol Foundation to “deauthenticate” his work is an utterly false, reckless claim, and completely unsupported by the facts. And here are the facts to set the record straight: the board and the foundation are separate and independent charitable organizations. The board, comprised of experts in the field noted for their integrity and scholarly excellence, conducts thoughtful, reasoned analysis of each work and engages in deliberations to reach decisions that are completely independent, by design, from the foundation.

Mr. Mearns’s work is one in a series of works that the board determined are not the work of Andy Warhol. The board detailed the specific reasons and evidence that led to its determination concerning this series of works in letters to owners of works in this series and Joe Simon-Whelan, one of these owners, has posted the letter on his Web site—given this, the board’s determination concerning this series of works can hardly be described as “secret” and was in fact quite transparent.

The foundation’s core mission is to protect and enhance the legacy of Andy Warhol, while also promoting the visual arts. All of the foundation’s charitable activities, including substantial grants, discounts on Warhol artwork, and outright donations to museums, colleges, and universities, are designed to further this mission, and particularly the Warhol legacy. The board also performs a critical role in preserving the Warhol legacy, and protecting buyers and sellers, by preventing inauthentic works from entering the market. Mr. Mearns’s views are a damaging distortion of the truth and are motivated by his own economic self-interests that don’t stand up to the facts.

Joel Wachs

President

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts New York City

To the Editors:

I have never met Joel Wachs. I have never spoken to Ronald Spencer about Andy Warhol. Mr. Dorment’s statement [“What Is a Warhol?: An Exchange,” NYR, December 17, 2009] that I “failed to mention” that I was a contributor to The Expert versus the Object is, as you must well know, untrue.

With my letter to you of October 6, 2009, I included a single-page autobiographical outline. With a yellow pen I highlighted the penultimate sentence which reads as follows: “He is a contributing author of The Expert versus The Object: Judging Fakes and False Attributions in the Visual Arts published by Oxford University Press in 2004.”

Michael Findlay

Director Acquavella Contemporary Art, Inc. New York City

Richard Dorment replies:

At first it surprised me that Joel Wachs, the president of the Andy Warhol Foundation, chose to respond to David Mearns’s letter rather than to the even more trenchant criticisms of the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board by Charles Lutz. Mr. Lutz pointed out in his letter in the December 17 issue that the board has authenticated more than $70 million worth of Brillo Box sculptures made three years after the artist’s death. Not only did its experts include these works in their catalogue raisonné, published in 2004, but even now they have failed to remove them from Warhol’s oeuvre. Damaging as that is, I gradually came to understand that it is not Charles Lutz who is the Warhol Board’s worst nightmare—it is David Mearns.

For the pending lawsuit by Joe Simon-Whelan against the Warhol Foundation is not only about whether Andy Warhol’s series of Red Self Portraits are authentic. It is about whether, knowing that the 1965 “Bruno B” Red Self Portrait was in fact authentic—it was signed by Warhol and dedicated by him in 1969 to his longtime Swiss dealer Bruno Bischofberger (“To Bruno B Andy Warhol 1969”)—the board suppressed this primary evidence of Warhol’s working methods in the mid-1960s. If so, it worked in three ways: first by defacing the picture by stamping it with the word “DENIED,” second by silently deleting the picture from its catalogue raisonné as if it had never existed, and third by contacting owners of other paintings in the series, inviting them to submit their pictures to the authentication board with the apparently deliberate intention of mutilating them. As Wachs casually admits in his letter, the work owned by the Mearns family (which the board has never seen) “is one in a series of works that the Board determined are not the work of Andy Warhol.”

Advertisement

But if the board knew that already (in 2002 they had declared inauthentic the Red Self Portrait owned by Simon-Whelan, and in 2003 they also rejected the “Bruno B” Red Self Portrait now owned by the London art dealer Anthony d’Offay), why did they write an unsolicited letter in 2004 to the Mearns family inviting them to submit their picture for the board’s inspection? And why did they do so without telling Mr. Mearns they had already decided that the entire series to which the picture belonged was inauthentic? The only possible purpose they could have had was to gain physical possession of the picture in order to make it worthless by stamping it with the word “DENIED.” Fortunately, Mr. Mearns realized what they were doing and refused to submit his family’s property to them.

Wachs writes that “the board detailed the specific reasons and evidence that led to its determination concerning this series of works in letters to owners of works in this series.” By doing this, he concludes, the board’s decision-making process “can hardly be described as ‘secret’ and was in fact quite transparent.” This is simply not true. What happened is this. In 2002 the board returned Simon-Whelan’s Red Self Portrait stamped “DENIED” without explanation. Simon-Whelan then did more research into the picture’s provenance and submitted it to the board again. Once more it was returned denied, again without explanation.

In fact it took more than two years and the publication of articles critical of the board in Vanity Fair, The Art Newspaper, and ARTnews —not to mention a threatened lawsuit—to force the board finally to come clean. Only then did it give the owners “the specific reasons and evidence” for denying their pictures. But as I explained in detail in my article in the October 22 issue, not one of the reasons it ultimately gave for denying the picture stands up to critical examination. And while you can indeed now find the letter from the board stating its reasons for rejecting Joe Simon-Whelan’s Red Self Portrait on his Web site, myandywarhol.com, it was not started until 2008 and so was of no use to the Mearns family in 2004.

The case now hinges not only on whether the “Bruno B” Red Self Portrait owned by d’Offay is genuine but also on when the picture first came to the authentication board’s attention. As I have written, before the picture’s existence was known to the board, it might have been possible to reject other paintings in the series of Red Self Portraits in good faith. But from the moment members of the board saw a signed, dated, and dedicated portrait that had been published in a catalogue raisonné during Warhol’s lifetime, their earlier position was no longer tenable.

At that point they had a choice: they could treat the picture as tangible proof that Warhol was working in this way—i.e., by telephoning instructions to the printer, without being present during the silk-screening process—long before they had previously believed this to be the case. They would then presumably have been obliged to tell other owners of Red Self Portraits that the issue of the work’s authenticity was under review. Alternatively, they could stamp the picture “DENIED” and erase the evidence of its existence by omitting it from their catalogue raisonné. If during the discovery process of the pending lawsuit it emerges that the authentication board chose this latter course of action and then continued to solicit owners of other works in the series to submit their pictures with the apparent intention of rendering them inauthentic, and hence of little value, they could stand accused of a serious crime: conspiring, as the plaintiffs in the pending lawsuits allege, to defraud owners like the Mearns family of their property.

Let us look at some dates. On May 21, 2003, the board wrote to the then owner of the “Bruno B” Red Self Portrait, stating that the picture was not by Andy Warhol.1 Mr. Mearns writes that he received a letter inviting him to submit his family’s picture from the same series to the board in the spring of 2004, approximately a year later. Unable to dispute this, Wachs attempts to discredit David Mearns by calling his letter “an utterly false, reckless claim” and “a damaging distortion of the truth…motivated by his own economic self-interests that don’t stand up to the facts.” Vicious as these slurs are, Wachs produces not a shred of evidence to back them up. What distortion? What self-interests? What facts? In truth, David Mearns is a successful businessman who has not indicated any plans to sell his Red Self Portrait, and who wrote to this paper simply to describe his personal experience of how the authentication board operates. Wachs needs to smear him because what Mearns has to say calls into question the methods, the ethics, and the credibility of the board.

In his original letter to this paper, which he subsequently withdrew, Michael Findlay cited the book titled The Expert versus the Object: Judging Fakes and False Attributions in the Visual Arts. But he did not include what was, for me, the most interesting thing about the book: the name of the editor, Ronald D. Spencer, who is the lawyer for the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board. Since this citation came at the end of Findlay’s long letter disputing my criticism of the authentication board, it seemed a strange omission. More important, the editor of The New York Review asked Findlay to answer a question: “Had his gallery [Acquavella] ever purchased a work by Andy Warhol directly from the Andy Warhol Foundation?” The New York Review has still not received an answer.

I can well understand Wachs’s frustration at his inability to challenge the accuracy of anything I’ve written about the board and its methods. He is welcome to defend the interests of the foundation by engaging in open debate. Instead, he has responded by slinging mud. As described so vividly in the letter by Paul Alexander, smearing its critics seems to be the house style at the Andy Warhol Foundation. Last month, following his visit to the offices of the Review, Wachs sent a letter to the editor in which he accused me of putting pressure on members of the authentication board to authenticate another Warhol piece that Simon-Whelan had submitted to the board in 2003. Once again, this is a calculated distortion of the truth.

I never suggested to the late board member Robert Rosenblum or to anyone else on the board that any work owned by Joe Simon-Whelan was authentic—for the excellent reason that, as I wrote in a letter to the board of May 7, 2003: “I do not pretend to be an expert on Warhol, nor would I presume to comment on the authenticity of the work owned by Mr Simon.”2 But don’t take my word for it. Having seen the innocuous documents produced by Wachs as “proof” of his accusations, the editor of this paper refused to publish his letter, writing to him on December 9, 2009, to refute each allegation line by line, and concluding that “we did not find that what you say [in your letter] is borne out by the documents you gave us.”

Though Wachs had now been told that he had nothing of substance to back up his allegations, he nevertheless repeated them in The Guardian. But this too backfired when, after being shown the same documents, the editor printed a full correction both in the paper and on its Web site.

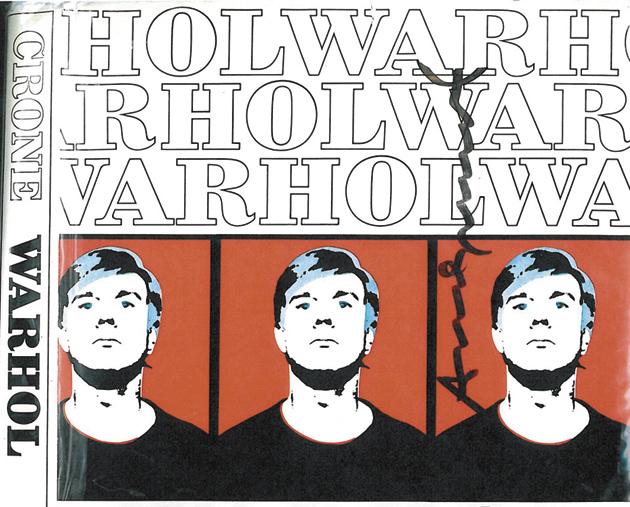

Wachs’s motives could hardly be more transparent. As Paul Alexander discovered when confronted with a list of one hundred “errors” that turned out not to be errors at all, when the foundation is unable to answer legitimate questions, it seeks to discredit the journalist who asks them. Wachs is using these diversionary tactics to shift attention away from the question I asked him and the Warhol Authentication Board about the “Bruno B” Red Self Portrait owned by Anthony d’Offay: How can a painting Andy Warhol signed, dated, inscribed, included in a catalogue raisonné published during his lifetime, and then personally approved for reproduction in color on the catalog’s cover not be by him? In a letter published on The New York Review Web site, Rainer Crone, the author of Warhol’s authoritative 1970 catalogue raisonné, shows that the painting is authentic.3

I am far from the only person still awaiting Wachs’s explanation. It is of interest to museum directors, curators, conservation scientists, auctioneers, gallerists, art historians, and—not least—the many writers queuing up to write about a case that has echoes of Jeffrey Wingard’s exposure of the tobacco industry in the 1970s. Meanwhile, there has been an unforeseen development in the case of the Red Self Portraits. On January 15, after I submitted the text of this letter to the Review, the sister of David Mearns filed an antitrust action against the Andy Warhol Foundation, Vincent Freemont, and “all past and present members of the authentication board who knowingly participated in, or wilfully ignored” an alleged “twenty-year scheme of fraud, collusion, and manipulation to control the market in works of art by the late Andy Warhol.” The decision to take action against the foundation had not been made when David Mearns wrote to the Review in November.

When contacted by e-mail David Mearns told me that although Wachs’s comments about him (which were printed in The Guardian and are repeated in Wachs’s letter above) were upsetting and erroneous, they did not influence his family’s decision to bring this lawsuit against the board. Even so, before Wachs went to work the Warhol Foundation had only David Mearns’s written testimony in support of the Simon-Whelan lawsuit to fear. Now their lawyers will be defending a second lawsuit, and members of the Mearns family will be telling what they know to a judge.

This Issue

February 25, 2010

Food

A Deal with the Taliban?

The Triumph of Madame Chiang

-

1

The authentication board met to review the “Bruno B”Red Self Portrait on February 24, 2003. Ten days later, on March 6, the then owners (Charles and Helen Schwab) received a letter signed by the board’s assistant secretary, Claudia Defendi, which said, “Further research is required, therefore the Board would like to request that the painting remain here and be reviewed again at the next board meeting on June 9, 2003.” On May 21, almost three weeks before Defendi had told the owner the board would meet, the owner received a formal letter signed by board member Neil Printz stating that “the said work is not the work of Andy Warhol, but said work was signed, dedicated, and dated by him.” ↩

-

2

This letter is in the archives of the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board. ↩

- 3