I am their leader, I had to follow them.

—French radical Ledru-Rollin, 1848

A little over a decade ago I published an article in these pages titled “A Tale of Two Reactions” (May 14, 1998). It struck me then that American society was changing in ways conservative and liberal commentators just hadn’t noticed. Conservatives were too busy harping on the cultural revolution of the Sixties, liberals on the Reagan revolution’s “culture of greed,” and all they could agree on was that America was beyond repair.

The American public, meanwhile, was having no trouble accepting both revolutions and reconciling them in everyday life. This made sense, given that they were inspired by the same political principle: radical individualism. During the Clinton years the country edged left on issues of private autonomy (sex, divorce, casual drug use) while continuing to move right on economic autonomy (individual initiative, free markets, deregulation). As I wrote then, Americans saw “no contradiction in holding down day jobs in the unfettered global marketplace…and spending weekends immersed in a moral and cultural universe shaped by the Sixties.” Democrats were day-trading, Republicans were divorcing. We were all individualists now.

What happened? People who remember the article sometimes ask me this, and I understand why. George W. Bush, who ran on a platform of “compassionate conservatism,” seemed attuned to the recent social changes. The President Bush who emerged after September 11 took his party and the country back to the divisive politics of earlier decades, giving us seven years of ideological recrimination. By the time of the last presidential campaign, millions were transfixed not by the wisdom or folly of Barack Obama’s policy agenda, but by absurd rumors about his birth certificate and his “socialism.” Now he has been elected president by a healthy majority and is grappling with a wounded economy and two foreign wars he inherited—and what are we talking about? A makeshift Tea Party movement whose activists rage against “government” and “the media,” while the hotheads of talk radio and cable news declare that the conservative counterrevolution has begun.

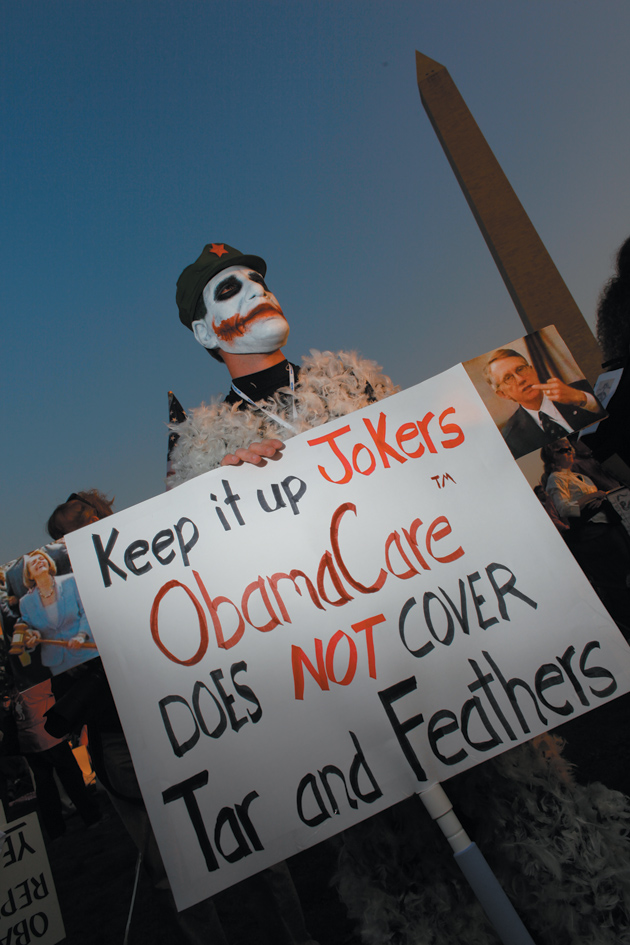

It hasn’t. We know that the country is divided today, because people say it is divided. In politics, thinking makes it so. Just as obviously, though, the angry demonstrations and organizing campaigns have nothing to do with the archaic right–left battles that dragged on from the Sixties to the Nineties. The populist insurgency is being choreographed as an upsurge from below against just about anyone thought to be above, Democrats and Republicans alike. It was galvanized by three things: a financial collapse that robbed millions of their homes, jobs, and savings; the Obama administration’s decision to pursue health care reform despite the crisis; and personal animosity toward the President himself (racially tinged in some regions) stoked by the right-wing media.1 But the populist mood has been brewing for decades for reasons unrelated to all this.

Many Americans, a vocal and varied segment of the public at large, have now convinced themselves that educated elites—politicians, bureaucrats, reporters, but also doctors, scientists, even schoolteachers—are controlling our lives. And they want them to stop. They say they are tired of being told what counts as news or what they should think about global warming; tired of being told what their children should be taught, how much of their paychecks they get to keep, whether to insure themselves, which medicines they can have, where they can build their homes, which guns they can buy, when they have to wear seatbelts and helmets, whether they can talk on the phone while driving, which foods they can eat, how much soda they can drink…the list is long. But it is not a list of political grievances in the conventional sense.

Historically, populist movements use the rhetoric of class solidarity to seize political power so that “the people” can exercise it for their common benefit. American populist rhetoric does something altogether different today. It fires up emotions by appealing to individual opinion, individual autonomy, and individual choice, all in the service of neutralizing, not using, political power. It gives voice to those who feel they are being bullied, but this voice has only one, Garbo-like thing to say: I want to be left alone.

A new strain of populism is metastasizing before our eyes, nourished by the same libertarian impulses that have unsettled American society for half a century now. Anarchistic like the Sixties, selfish like the Eighties, contradicting neither, it is estranged, aimless, and as juvenile as our new century. It appeals to petulant individuals convinced that they can do everything themselves if they are only left alone, and that others are conspiring to keep them from doing just that. This is the one threat that will bring Americans into the streets.

Advertisement

Welcome to the politics of the libertarian mob.

If we want to understand what today’s populism is about, we first need to understand what it isn’t about. It certainly is not about reversing the cultural revolution of the Sixties. Despite the rightward drift of the Republican Party over the past decade, the budding liberal consensus on social issues I noted in the Nineties has steadily grown—with the one, complicated exception of abortion.2

Consider the following:

• Since 2001 the proportion of those favoring more religious influence in society has dropped by a fifth, while those wanting less influence rose by half.3

• Today a majority of Americans find single parenthood morally acceptable, and nearly three quarters now tolerate divorce.4 Roughly a third of adults who have ever been married have also been divorced at least once, and that includes born-again Christians, whose rate is roughly the national average.5

• Though opposition to gay marriage has declined over the past quarter-century, a majority still opposes it. Yet more than half of all Americans find homosexuality morally acceptable, and a large majority favors equal employment opportunities for gays and lesbians, health and other benefits for their domestic partners, and letting them serve in the military. A smaller majority now approves of letting them legally adopt children as well.6

Though there’s been a slight conservative retrenchment since the 2008 election, it’s clear that the Sixties principle of private autonomy is rooted in the American mind.

And so is the Eighties principle of economic autonomy. For three decades now a consistent majority of Americans has agreed with the following statements when asked: “when something is run by the government, it is usually inefficient and wasteful,” “the federal government controls too much of our daily lives,” “government regulation of business usually does more harm than good,” and “poor people have become too dependent on government assistance programs.” Yet there is no widespread desire to push the Reagan agenda of the Eighties further. The ideological polarization between Republicans and Democrats that surveys pick up is owing almost entirely to the radicalization of those belonging to the shrunken Republican base. (As of 2009, only a quarter of Americans identified themselves as Republicans, the lowest figure since the post-Watergate years.)

Democrats have edged slightly more left on political and economic issues, whereas the views of independents, the largest and fastest-growing group of voters, have not changed much over the years. While well over half of Republicans say that they would like their party to move further to the right, just as many independents wish it was less conservative or would stay where it is. The Reagan revolution was a success, in the sense that it shifted political attention in this country from social equality to economic growth. But like all revolutions that achieve their aims, it is now a spent force.7

So what is the new populism about? That depends on who grabs your lapel. Glenn Beck, Keeper of the Grand Narrative at Fox News, fills his blackboard with circles and arrows mapping out the network of elites who have been plotting to seize control of our lives for over a century—from Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson to George Soros, the Federal Reserve Board, the G7, the UN, and assorted left-wing professors. The economic collapse and financial bailout they have exploited (or more likely caused) have woken the American people from their slumbers and now they are “taking their country back,” which apparently involves anesthetizing the government and buying gold (which Beck promotes on his program). In his lurid book Republican Gomorrah, Max Blumenthal of the Nation Institute sees an entirely different sort of cabal on the Republican right, whose leaders he portrays as sadomasochistic, porn-addicted, child-beating Christian fanatics who share with their Palin-loving followers “a culture of per- sonal crisis lurking behind the histrionics and expressions of social resentment.” (“Gingrich grew his hair long, emulating the style of the counterculture that he secretly yearned to join.”)

If either Beck or Blumenthal is right about the new populism, then it’s not worth taking seriously. My own view is that we need to take it even more seriously than they do; we need to see it as a manifestation of deeper social and even psychological changes that the country has undergone in the past half-century. Quite apart from the movement’s effect on the balance of party power, which should be short-lived, it has given us a new political type: the antipolitical Jacobin. The new Jacobins have two classic American traits that have grown much more pronounced in recent decades: blanket distrust of institutions and an astonishing—and unwarranted—confidence in the self. They are apocalyptic pessimists about public life and childlike optimists swaddled in self-esteem when it comes to their own powers.

Advertisement

Ever since the Seventies, social scientists have puzzled over the fact that, despite greater affluence and relative peace, Americans have far less trust in their government than they had up until the mid-Sixties. Just before the last election, only a tenth of Americans said that they were “satisfied with the way things are going in the United States,” a record low.8 They express some confidence in the presidency and the courts, but when asked in the abstract about “the government” and whether they expect it to do the right thing or whether it is run for our benefit, a relatively consistent majority says “no.”9 It’s important to remember that the confidence they express in free markets and deregulation is only relative to their sense that government no longer functions as it should.

And they are not alone. Survey after survey confirms that trust in government is dissolving in all advanced democratic societies, and for the same reason: as voters have become more autonomous, less attracted to parties and familiar ideologies, it has become harder for political institutions to represent them collectively.10 This is not a peculiarity of the United States and no one party or scandal is to blame. Representative democracy is a tricky system; it must first give citizens voice as individuals, and then echo their collective voice back to them in policies they approve of. That is getting harder today because the mediating ideas and institutions we have traditionally relied on to make this work are collapsing.

In Western Europe, the collapse is ideological. For two centuries after the French Revolution there was a rough but evident distinction between Europeans who accepted its legacy and those who, in small ways or large, rejected it. Each side had its parties, its newspapers, its heroes, its enemies, its own account of history. That ideological distinction began to fade in the postwar years as Western Europe’s new consumer societies became more atomized and hedonistic, and with the collapse of communism it became meaningless. At the same time, European political elites were busy blurring national identities in order to construct a faceless “Europe,” whose eerily blank currency is a powerful symbol of the crisis of representation there. It would occur to no one to lay siege to Brussels or build barricades to defend it. Xenophobic, anti-immigrant parties have cropped up instead, giving cruel expression to genuine mourning for a lost sense of belonging.

The new American populism is not, by and large, directed against immigrants. Its political target is an abstract noun, “the government,” which has been a source of disenchantment since the late Sixties. In Why Trust Matters, Marc Hetherington uncovers the astonishing fact that in 1965 nearly half of Americans believed that the War on Poverty would “help wipe out poverty”—a vote of confidence in our political institutions unimaginable today. The failure of the Great Society programs to meet the high expectations invested in them was a major source of disappointment and loss of confidence.

The disappointment only grew in subsequent decades, as Congress seemed less and less able to act decisively and legislate coherently. There are many reasons for this, some of them perverse consequences of reforms meant to make government more open and responsive to the public. New committees and subcommittees were established to focus on narrower issues, but this had the unintended effect of making them more susceptible to lobbyists and the whims of powerful chairmen. Congressional hearings began to be televised and campaign finances were made public, but as a result individual congressmen and senators became more self-sufficient and could ignore party dictates. Coalitions broke apart, large initiatives stalled, special interest legislation and court orders piled up, government grew more complex and less effective. And Americans noticed. Not recognizing themselves in the garbled noises coming out of Washington, unsure what the major parties stood for, they drew the conclusion that their voices were being ignored. Which was not exactly true. It’s just that, paradoxically, more voice has meant less echo.

Yet until now we’ve somehow muddled along. Since the Seventies, distrust of politics has been the underlying theme of our politics, and every presidential candidate since Jimmy Carter has been obliged to run against Washington, knowing full well that the large forces making the government less effective and less representative were beyond his control. Voters pretend to rebel and politicians pretend to listen: this is our political theater. What’s happening behind the scenes is something quite different. As the libertarian spirit drifted into American life, first from the left, then from the right, many began disinvesting in our political institutions and learning to work around them, as individuals.

The simplest way to do that is to move. As the journalist Bill Bishop shows in his eye-opening demographic study The Big Sort, for decades we have been withdrawing into “communities of like-mindedness” where the gap between individual and collective closes. These are places where elective affinities are supplanting electoral politics. People with higher degrees who care about food and wine, support gay rights, and want few children but good Internet connections have been gravitating to urban centers on the two coasts, while churchgoing families that drive everywhere, socialize with relatives, and send their kids to state universities have been heading to the growing exurbs of the southern and mountain states. By voting with their feet, highly mobile Americans are finding representation in local communities where they share their neighbors’ general political outlook and where they can be sure that their voices will be echoed back to them. As Bishop points out, it is significant that at the county level American elections are increasingly being decided by landslides for either Democratic or Republican candidates.

Another way is simply to go it alone. A million and a half students in the United States are now being taught by their parents at home, nearly double the number a decade ago, and representing about fifteen students for every public school in the country.11 There is nothing remarkable about wanting to escape unsafe schools and incompetent teachers, or to make sure your children are raised within your religious tradition. What’s remarkable is American parents’ confidence that they can do better themselves. Many of the more-educated ones probably do, though they are hardly going it alone; they rely on a national but voluntary virtual school system connecting them online, where they circulate curricula, materials, and research produced by people working in conventional educational institutions. And they are a powerful political lobby, having redirected their energy from local school systems to Washington and state capitals, where their collective appeal to individualism is irresistible. They are the only successful libertarian party in the United States.

But as the libertarian spirit has spread to other areas of our lives, along with distrust of elites generally, the damage has mounted. Take health care. Less than half of us say that we have “great confidence” in the medical establishment today, and the proportion of those who have “hardly any” has doubled since the early Seventies.12 There are plenty of things wrong with the way medicine is practiced in the United States, but it does not follow from this that anybody can cure himself. Nonetheless, a growing number of us have become our own doctors and pharmacists, aided by Internet search engines that substitute for refereed medical journals, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Centers for Disease Control.

The trends are not encouraging. Because of irrational fear-mongering on the Web, the percentage of unvaccinated American children, while thankfully still low, has been rising steadily in the twenty-one states that now allow personal exemptions for unspecified “philosophical and personal reasons.” This is significant: the chance of unvaccinated children getting measles, to take just one example, is twenty-two to thirty-five times higher than that of immunized children.13 Americans currently spend over four billion dollars a year on unregulated herbal medicines, despite total ignorance about their effectiveness, correct dosage, and side effects. And of course, many dangerous medicines banned in the United States can now be purchased online from abroad, not to mention questionable medical procedures for those who can afford the airfare.14

Americans are and have always been credulous skeptics. They question the authority of priests, then talk to the dead15; they second-guess their cardiologists, then seek out quacks in the jungle. Like people in every society, they do this in moments of crisis when things seem hopeless. They also, unlike people in other societies, do it on the general principle that expertise and authority are inherently suspect.

This, I think, is the deepest reason why public reaction to the crash of 2008 and the election of Barack Obama took a populist turn and the Tea Party movement caught on. The crash not only devastated people’s finances and shook their confidence in their and their children’s future. It also broke through the moats we have been building around ourselves and our families, reminding us that certain problems require a collective response through political institutions. What’s more, it was a catastrophe whose causes no one yet fully understands, not even specialists who know exactly what derivatives, discount rates, and multiplier effects are. The measures the federal government took to control the damage were complex and controversial, but there was general agreement that at some point it would have to intervene to prevent a worldwide financial collapse, and that without some sort of stimulus a real depression loomed. That, though, is not at all what people who distrust elites, who want to “make up their own minds,” and who have fantasies of self-sufficiency want to be told. Apparently they find it more satisfying to hear that these emergency measures were concocted to tighten government’s grip on their lives even more. It all connects.

Which brings us to Fox News. The right-wing demagogues at Fox do what demagogues have always done: they scare the living daylights out of people by identifying a hidden enemy, then flatter them until they believe they have only one champion—the demagogue himself. But unlike demagogues past, who appealed over the heads of individuals to the collective interests of a class, Fox and its wildly popular allies on talk radio and conservative websites have at their disposal technology that is perfectly adapted to a nation of cocksure individualists who want to be addressed and heard directly, without mediation, and without having to leave the comforts of home.

The media counterestablishment of the right gives them that. It offers an ersatz system of direct representation in which an increasingly segmented audience absorbs what it wants from its trusted sources, embellishes it in their own voices on blogs and websites and chatrooms, then hears their views echoed back as “news.” While this system doesn’t threaten our system of representative democracy, it certainly makes it harder for it to function well and regain the public’s trust.

The conservative media did not create the Tea Party movement and do not direct it; nobody does. But the movement’s rapid growth and popularity are unthinkable without the demagogues’ new ability to tell isolated individuals worried about their futures what they want to hear and put them in direct contact with one another, bypassing the parties and other mediating institutions our democracy depends on. When the new Jacobins turn on their televisions they do not tune in to the PBS News Hour or C-Span to hear economists and congressmen debate the effectiveness of financial regulations or health care reform. They look for shows that laud their common sense, then recite to them the libertarian credo that Fox emblazons on its home page nearly every day: YOU DECIDE.

A familiar American ritual is now being performed in homes across the country. Meetings are being called. Coffee is brewed, brownies baked, hands raised, votes tallied, envelopes licked, fliers mailed. We Americans are inducted into this ritual’s mysteries at an early age, and by the time we reach high school we may not read well but we certainly know how to organize an election campaign and build a homecoming float.

But what happens after the class president is sworn in and the homecoming queen is crowned? The committees dissolve and normal private life resumes. And that, I suspect, is what will happen to the Tea Party organizations: after tasting a few symbolic victories they will likely dissolve. This is not only because, being ideologically allergic to hierarchy of any kind, they still have no identifiable leadership. It is because they have no constructive political agenda, though the right wing of the Republican Party would dearly love to attach its own to them. But the movement only exists to express defiance against a phantom threat behind a real economic and political crisis, and to remind those in power that they are there for one thing only: to protect our divine right to do whatever we damn well please. This message will be delivered, and then the messengers will go home. Every man a Cincinnatus.

Still, the Jacobin spirit could shape our politics for some time, given how well it dovetails with the spirits of Woodstock and Wall Street, and given the continuing influence of Fox News and talk radio. (Rush Limbaugh alone has millions of daily listeners.) It is already transforming American conservatism. A wise man once summed up the history of colonialism in a phrase: the colonized eventually colonize the colonizer. This is exactly what is happening on the right today: the more it tries to exploit the energy of the Tea Party rebellion, the cruder the conservative movement becomes in its thinking and rhetoric. Ronald Reagan was a master of populist rhetoric, but he governed using the policy ideas of intellectuals he knew and admired (Milton Friedman, Irving Kristol, George Gilder, and Charles Murray among them).

Today’s conservatives prefer the company of anti-intellectuals who know how to exploit nonintellectuals, as Sarah Palin does so masterfully.16 The dumbing-down they have long lamented in our schools they are now bringing to our politics, and they will drag everyone and everything along with them. As David Frum, one of the remaining lucid conservatives, has written to his wayward comrades, “When you argue stupid, you campaign stupid. When you campaign stupid, you win stupid. And when you win stupid, you govern stupid.” (Unsurprisingly, Frum was recently eased out of his position at the American Enterprise Institute after expressing criticism of Republican tactics in the health care debate.)

Over the next six months, as midterm elections approach, we’ll be hearing a lot from and about the Tea Party movement. Right-wing Republicans hope to lead the movement by following it. Establishment Republicans will make fools of themselves trying to master a populist rhetoric they don’t know and don’t believe in. Democrats will take cover, hoping that their losses won’t be too great and that they’ll pick up seats in places where Republicans are slitting each other’s throats. In the end we will likely find ourselves with a divided and irresponsible Congress even less capable of gaining public trust by governing well. Confidence in government will drop further and the libertarian commedia of American politics will extend its run.

But the blame does not fall on Fox News or Rush Limbaugh or Glenn Beck or the Republican Party alone. We are experiencing just one more aftershock from the libertarian eruption that we all, whatever our partisan leanings, have willed into being. For half a century now Americans have been rebelling in the name of individual freedom. Some wanted a more tolerant society with greater private autonomy, and now we have it, which is a good thing—though it also brought us more out-of-wedlock births, a soft pornographic popular culture, and a drug trade that serves casual users while destroying poor American neighborhoods and destabilizing foreign nations. Others wanted to be free from taxes and regulations so they could get rich fast, and they have—and it’s left the more vulnerable among us in financial ruin, holding precarious jobs, and scrambling to find health care for their children. We wanted our two revolutions. Well, we have had them.

Now an angry group of Americans wants to be freer still—free from government agencies that protect their health, wealth, and well-being; free from problems and policies too difficult to understand; free from parties and coalitions; free from experts who think they know better than they do; free from politicians who don’t talk or look like they do (and Barack Obama certainly doesn’t). They want to say what they have to say without fear of contradiction, and then hear someone on television tell them they’re right. They don’t want the rule of the people, though that’s what they say. They want to be people without rules—and, who knows, they may succeed. This is America, where wishes come true. And where no one remembers the adage “Beware what you wish for.”

—April 29, 2010

This Issue

May 27, 2010

-

1

As a recent CBS/New York Times poll shows, though Tea Party members portray themselves as representing middle America, in fact they are overwhelmingly white, older, educated, and with higher-than-average incomes. They are also more likely to feel that too much has been made of race in America and that President Obama’s policies favor poor blacks over the white middle class. See “Tea Party Supporters: Who They Are and What They Believe” (April 14, 2010), at [www.cbsnews.com](http://www.cbsnews.com), which also has links to the raw survey data. ↩

-

2

While more Americans are identifying themselves as pro-life today, the proportion of those who want abortion to remain legal under certain circumstances has remained roughly constant for thirty-five years; it is the proportion of those who want abortion to be legal under all circumstances that has dropped dramatically over the past two decades, and the proportion of those in favor of a total ban that has increased.

Changes in the social context of the abortion debate should also be taken into consideration. Since the time of Roe v. Wade, a monument to the new individualism, contraception has become readily available and inexpensive, the moral stigma of single-motherhood has lessened, and the demand for infants to adopt has grown. Given this background, more people today (women especially) are concluding that expectant mothers have a greater obligation to bring fetuses to term—fetuses who, given advances in ultrasound technologies, now appear vividly as individuals in their own right.

For slightly contrasting studies, compare the report of the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, “Support for Abortion Slips,” available at people-press.org/report/549/support-for-abortion-slips and Gallup’s long-term trend data at [www.gallup.com/poll/122033/U.S.-abortion-attitudes-closely-divided.aspx](http://www.gallup.com/poll/122033/U.S.-abortion-attitudes-closely-divided.aspx). ↩ -

3

See trend data at [www.gallup.com/poll/1690/religion.aspx](http://www.gallup.com/poll/1690/religion.aspx). ↩

-

4

See Lydia Saad, “Cultural Tolerance for Divorce Grows to 70%,” May 19, 2008, available at [www.gallup.com/poll/107380/cultural-tolerance-divorce-grows-70.aspx](http://www.gallup.com/poll/107380/cultural-tolerance-divorce-grows-70.aspx). See the trend data at [www.gallup.com/poll/117328/marriage.aspx](http://www.gallup.com/poll/117328/marriage.aspx). ↩

-

5

See Barna Group, “New Marriage and Divorce Statistics Released,” March 31, 2008, available at [www.barna.org/barna-update/article/15-familykids/42-new-marriage-and-divorce-statistics-released](http://www.barna.org/barna-update/article/15-familykids/42-new-marriage-and-divorce-statistics-released). ↩

-

6

For general trend data about attitudes toward homosexuality, see [www.gallup.com/poll/1651/gay-lesbian-rights.aspx](http://www.gallup.com/poll/1651/gay-lesbian-rights.aspx). For slightly different figures and survey questions, see Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, “Majority Continues to Support Civil Unions,” October 9, 2009, available at [www.people-press.org/rep ort/553/same-sex-marriage](http://www.people-press.org/report/553/same-sex-marriage). ↩

-

7

On Independents, see Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, “Independents Take Center Stage in Obama Era,” May 21, 2009, overview and sections 1, 2, 3, and 11. See full report at [www.people-press.org/report/517/political-values-and-core-attitudes](http://www.people-press.org/report/517/political-values-and-core-attitudes). For slightly different and more recent figures, compare Lydia Saad, “Conservatives Maintain Edge as Top Ideological Group,” October 26, 2009, at [www.gallup.com/poll/123854/conservatives-maintain-edge-top-ideological-group.aspx](http://www.gallup.com/poll/123854/conservatives-maintain-edge-top-ideological-group.aspx), and Frank Newport, “Americans More Likely to Say Government Doing Too Much,” September 21, 2009, at [www.gallup.com/poll/123101/americans-likely-say-government-doing-too-much.aspx](http://www.gallup.com/poll/123101/americans-likely-say-government-doing-too-much.aspx). Note that the slight rightward drift of independents that these surveys picked up is mainly due to the fact that so many moderate conservatives have abandoned the Republicans and now call themselves independents.

On independent and Republican views on the Republican Party, see [www.gallup.com/poll/24655/party-images.aspx](http://www.gallup.com/poll/24655/party-images.aspx). ↩ -

8

See the Pew Research Center’s Databank report on “National Satisfaction” at [www.pewresearch.org/databank/dailynumber/?NumberID=11](http://www.pewresearch.org/databank/dailynumber/?NumberID=11). For trend data see National Election Survey, “Guide to Public Opinion and Electoral Behavior,” section 5A, available at [www.electionstudies.org/nesguide/gd-index.htm#5](http://www.electionstudies.org/nesguide/gd-index.htm#5). ↩

-

9

See references in footnote 7. These results are consistent across many different polls and polling organizations; see [www.pollingreport.com/institut.htm/Federal](http://www.pollingreport.com/institut.htm/Federal). ↩

-

10

For results of a sixteen-nation study, see Russell J. Dalton, “The Social Transformation of Trust in Government,” International Review of Sociology (March 2005), pp. 133–154. ↩

-

11

See the ]:National Center for Education Statistics, Condition of Education 2009, “Indicator 6: Homeschooled Students,” available at [www.nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/2009/section1/indicator06.asp](http://www.nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/2009/section1/indicator06.asp). ↩

-

12

National Opinion Research Center, “General Social Surveys, 1972–2006,” under “Confidence.” [www.norc.org/GSS+Website/Browse+GSS+Variables/Subject+Index/](http://www.norc.org/GSS+Website/Browse+GSS+Vari ables/Subject+Index/). ↩

-

13

As of 2009, forty-eight states allow religious exemptions from vaccination, and twenty-one allow them based on philosophical or personal beliefs as well. The most recent study of the impact of these exemptions found that mean exemption rate increased an average of 6 percent per year, from 0.99 percent in 1991 to 2.54 percent in 2004, among states that offered personal belief exemptions. However there is great regional variety, even within states; for example, in from 2006 through 2007, in Washington State the county-level rate ranged from 1.2 to 26.9 percent. Exempt children are at much higher risk of coming down with vaccine-preventable illnesses; in one study their rate of measles was thirty-five times the rate of vaccinated children. See Saad B. Omer et al., “Vaccine Refusal, Mandatory Immunization, and the Risks of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases,” New England Journal of Medicine, May 7, 2009. [http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/360/19/1981/ijkey=b52fcc291ae978c57f6f41f1b02f97a47c30bd0d](http://www.content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/360/19/1981/ijkey=b52fcc291ae978c57f6f41f1b02f97a47c30bd0d). ↩

-

14

Pew reports that nearly half of Americans report having had a “mystical experience” or “spiritual awakening,” more than double the number in the early Sixties, when most believers attended mainline churches. Three out of ten say they have been in touch with the dead, two out of ten have seen ghosts. These figures are nearly double what they were twenty years ago. See the Pew Forum on Religious and Public Life, “Many Americans Mix Multiple Faiths,” December 9, 2009, at [www.pewforum.org/docs/?DocID=490](http://www.pewforum.org/docs/?DocID=490). ↩

-

15

See Denise Grady, “Scientists Say Herbs Need More Regulation,” The New York Times, March 7, 2000. ↩

-

16

Sarah Palin and Glenn Beck were treated like rock stars at this year’s Conservative Political Action Committee’s convention, and last year Rush Limbaugh stole the show by calling for a purge of moderate conservatives and elites within the movement. He said, in part: “We’ve got factions now within our own movement seeking power to dominate it, and worst of all to redefine it…. These people in New York and Washington, cocktail elitists, they get made fun of when the next NASCAR race is on TV and their cocktail buds come up to them, those people are in your party?… Beware of those different factions who seek as part of their attempt to redefine conservatism, as making sure the liberals like us, making sure that the media likes us [sic]. They never will, as long as we remain conservatives. They can’t possibly like us; they’re our enemy. In a political arena of ideas, they’re our enemy.” <[www.rushlimbaugh.com/home/daily/site_030209/content/01125106.guest.html](http://www.rushlimbaugh.com/home/daily/site_030209/content/01125106.guest.html)> This tirade helped to inspire the right-wing radicals who are now trying to purge Republican deviationists like Maine Senator Olympia Snowe, Florida Governor Charlie Crist, and even John McCain from the party. By threatening them with primary challenges, even if their defeat might ensure a Democratic victory, this suicide brigade has put all Republican officials on notice that they could be next. ↩