Against the backdrop of bloody upheaval in the Arab world, Turkey’s national election in June seemed a triumph of democracy. Candidates for parliament were secular and religious, pro-military and anti-military, in favor of Kurdish rights and opposed. Fifty million people were eligible to vote, and 87 percent turned out. There were no serious incidents. Votes were counted quickly and fairly.

The result was a decisive victory for Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. His party, Justice and Development, failed to win a supermajority in parliament that would have allowed him to promulgate the country’s much-anticipated new constitution almost by decree. Nonetheless it won more votes than all other parties combined, winning its third election in a row and making Erdogan the most powerful Turkish leader in more than half a century to win three consecutive terms. He now enjoys more power than any Turkish leader since Kemal Atatürk, who founded the Republic in 1923.

This victory was testimony to Erdogan’s accomplishments. Before Justice and Development won its first national election in 2002, Turkey had spent years under weak coalition governments servile to the military. It suffered periodic economic crises and was almost invisible on the world stage. All of that has changed. Erdogan’s strong single-party governments have broken the army’s political power, turned Turkey into an economic powerhouse, and made it a major force in the Middle East, the Caucasus, the Balkans, North Africa, and beyond.

Yet despite this, many Turks are uneasy. Some worry that the economy, which grew at a spectacular 8.9 percent last year, may be overheating. Others fear that Erdogan’s renewed power will lead him to antidemocratic excesses. A boycott of parliament by dozens of Kurdish deputies cast doubt on his willingness to resolve the long-festering Kurdish conflict. There is also a new source of uncertainty, emerging from uprisings in Arab countries. For the last several years, Turks have pursued the foreign policy goal of “zero problems with neighbors.” In recent months they have been forced to realize that they cannot, after all, be friends with everyone in the neighborhood.

Politically Turkey has changed more in the last ten years than it did in the previous eighty. For generations the army was able to enforce strict secularism in the tradition of Ataturk, but a new ethos, more open to religious influence, has changed the terms of politics and public life. Erdogan prays daily and his wife wears a headscarf. In some Turkish towns, Justice and Development mayors have sought to restrict the sale of alcohol or establish single-sex beaches. This has alarmed many secular-minded citizens. Erdogan could help calm their fears, but instead he has become increasingly strident. Turkey has emerged from the shadow of military power, a breakthrough of historic proportions. Whether it is moving toward an era of European-style freedom or simply trading one form of authoritarianism for another is unclear.

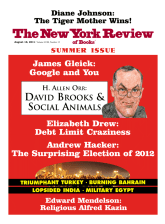

This Issue

August 18, 2011

What Were They Thinking?

Fooled by Science

How Google Dominates Us