In 1980, as Ronald Reagan was on his way to the White House, and as a college student still called Barry Obama was about to move from Occidental College to Columbia University and starting to think seriously about some kind of future in public service, Herman Cain was reporting to work at the Pillsbury Corporation. Cain had been working as a project manager at the Coca-Cola Company in Atlanta, where years before, his father, Luther, had been the chauffeur for CEO Robert Woodruff. He was thirty-two, an Atlanta native, doing quite well; but he felt that at Coca-Cola he would never quite shake being the chauffeur’s kid, so in 1977, off he went to Pillsbury, in faraway Minneapolis.

He was handed the task of integrating the management information systems of Pillsbury and the Green Giant frozen foods company, which his employer had acquired. Having completed this work (which included eliminating “obvious redundancies” in personnel), Cain was next charged with overseeing the construction of the Pillsbury world headquarters building, a charmless tower that still stands in downtown Minneapolis about six blocks from the Mississippi River. Construction was running late and over budget. But Herman Cain is, to use his pet phrase, a “CEO of Self,” and CEOs of Self not only don’t fear such problems, they welcome them as particularly fortunate opportunities to show their stuff. So Cain, after consulting with the company’s CEO and COO, knew what had to be done:

Given their input, I was not afraid to take charge, make decisions, and focus on the critical things I needed to do in order to get the project moving. Again, seeing myself as CEO of Self, I was determined not to fall into a comfort zone of letting other people, no matter how competent and well-meaning, make the decisions for me.

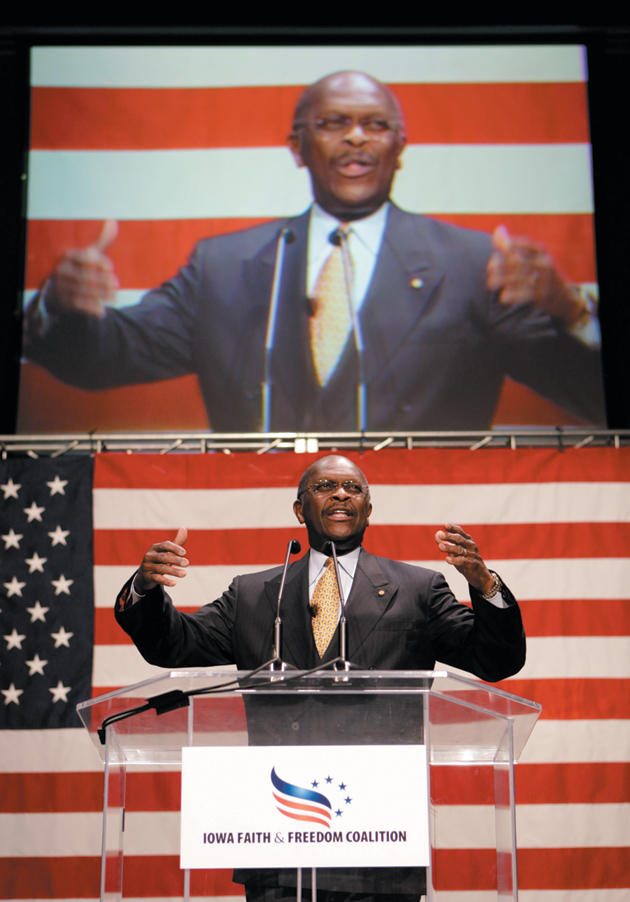

The headquarters project came in ahead of schedule and under budget, and the CEO later presented Cain with Pillsbury’s Symbol of Excellence in Leadership Award. So life has gone for Herman Cain, at least until the last few weeks as he has fended off sexual harassment charges and was embarrassed when, at a talk with a group of editors, he couldn’t articulate a view of Obama’s record on Libya. He has until recently succeeded at everything, mastered each task.

If one momentarily puts to the side his wildly extreme political views, his obvious and cringe-inducing knowledge gaps, and his alleged treatment of women, one can easily find things to admire in the man. Certainly, he does himself in This Is Herman Cain! It opens by describing how he “redefined campaign history” with his performance at a Republican debate last May, an event hardly remembered today; and it closes with Cain imagining what his first days in the White House will be like, taking the measure of heads of state, sifting through résumés, and mulling appointments (“Given my well-honed instinct for identifying the right people to get the job done, I know that I have chosen wisely”).

In other places, fewer of them to be sure, we catch glimpses of a different Cain—still working angles, still thinking about the quickest way to advance, but subordinating himself to the needs of the group or getting his hands dirty if he must pay the price of later glory. In eighth grade, he went to the band instructor, announcing his interest in joining up. Mr. Terry asked him what instrument he wanted to learn. He shocked Mr. Terry by asking him what instrument he needed the most. The answer was trombone. Cain took it up. By tenth grade, “I was the leader of the trombone section. A year later, I was chosen to be the band’s student director—the very first time a junior had been picked for that important position.”

During the Pillsbury years, a restless Cain was contemplating his next triumph after seeing the skyscraper through to completion. He was a well-off if not yet rich man, with an attentive wife and two children. But he needed more—he needed, he decided, to be president of something. He knew that he lacked experience in P&L—profit and loss; turning around an underperforming unit. A colleague suggested Burger King, which Pillsbury owned. So off he went. A man who had a thirty-first-floor office accepted a substantial salary cut, began shoving buns and patties through the char-broiler, and enrolled in Burger King University in Miami (“very well organized and very well run”). Did the CEO of Self find this demeaning? Not in the least:

In deciding whether to leave my comfortable corporate VP job at Pillsbury to start over at Burger King, I asked myself one question, the right question: Will this put me in a better position to become president of a business? I did not ask myself the wrong questions: How hard will my new job be? What will my friends think if they see me making hamburgers in a quick-service restaurant? What will I do if this new position does not work out as planned? As a CEO of Self, I knew that those questions were not the right ones to be asking.

The commonly held view in the political world is that Cain isn’t really serious about running—he’s trying to sell copies of his book and jack up his speaking fees. Journalists and analysts point, for example, to the fact that he has virtually no organization on the ground in Iowa or New Hampshire. It is possible that his recent missteps or the recent sexual harassment allegations, which have affected his poll numbers, will sink him, especially if one of his accusers comes forward with the kind of tidbit that has been lacking so far—that is, something both provable and salacious. If that doesn’t happen, January 3 will come, and Iowa will vote, and he will finish third or fourth, and that will be that. Certainly, the political establishment began writing him off in mid-November, collectively deciding that the Cain sideshow would soon be playing to smaller and smaller houses.

Advertisement

But after reading This Is Herman Cain!, I doubt very much that that is how he sees things. Cain is so serene, so certain of his superiority to most of those around him, so assured that he is carrying out God’s plan for him and for America (a conviction that solidified after he survived stage-four colon and liver cancer in 2006), that he thinks that in fact, it’s everyone else’s candidacy that is a joke or a lark. He writes like a man who is confident that he will wake up on January 20, 2013, ready to take the oath of office. To Cain, this has all been foreordained, at least from the time of his cancer, and more likely since he was appointed the first-ever student band director from the junior class. He doesn’t have a ground operation in New Hampshire because true CEOs of Self don’t need things like ground operations. They exert their will and they win.

Cain’s march up the corporate ladder figured centrally in his September surge toward the top of the GOP heap. Conservative voters like the fact that he is not a politician and comes from the corporate world. While some of us may scoff at a man whose claims to fame include peddling Whoppers (Cain turned around the Philadelphia regional division of Burger King) and pizzas (he was for ten years CEO of Godfather’s Pizza, which he also made profitable) to an increasingly obese nation with less and less need of them, conservatives find virtually any form of private-sector achievement admirable. So that helped get him in the door.

But something else is really at the heart of Cain’s appeal to conservatives: he is a right-wing black man who is visibly very pleased being a right-wing black man. Conservative voters have said they particularly like the way he confounds the “liberal media.” The New York Observer recently reported that a group of women waiting to glimpse Cain on a trip to New York were holding signs saying “Yes We Cain” (a reference to the famous Obama 2008 slogan) and “LOL @ mainstream media”—laugh out loud, that is.

Cain understands how to stoke these emotions. When Fox News’s Sean Hannity asked him in October to respond to Harry Belafonte’s remark on daytime television that Cain was “totally false” and a “bad apple,” he replied:

As far as Harry Belafonte’s comment, look, I left the Democrat plantation a long time ago. And all that they try to do when someone like me—and I’m not the only black person out there that shares these conservative views—the only tactic that they have to try and intimidate me and shut me up is to call me names, and this sort of thing. It just simply won’t work.

Those often-repeated words charm right-wing audiences. The very phrase “Democrat plantation” cleverly turns the tables on the hated elite and tells the audiences exactly what they believe and want to hear—that the liberals are the real racists. It also helps to play the victim card, the charge that “they” want to “shut me up,” a claim for which no serious evidence exists.

Once this formula is established, everything fits into it neatly. Cain makes a joke about not knowing the location of “Ubeki-beki-beki-beki-stan-stan”; when the media report the remark, Cain says (and his admirers agree) that the fuss over it is the fault of liberals and the press—in that particular case, Belafonte (again!) and Cornel West, who “don’t want black people to think for themselves.” Every slip he makes merely proves to his voters that he’s getting under liberals’ skins, which of all the virtues a conservative can have in this day and age is far and away the most important.

Advertisement

This strategy has even worked, to some extent, with regard to the sexual harassment allegations when they first appeared on Politico.com.1 African-American Republican Congressman Allen West of Florida, a Tea Party–backed member of the far right, was asked on November 11 by an interviewer from something called Conservative New Media to comment on “how the story [about Cain] came out with Politico, how you felt they’ve handled it, and what kind of treatment that conservatives get vis-à-vis liberal, and maybe more specifically conservative minorities get.” West picked up the cues embedded in the way that question was asked and replied: “Well, conservative minorities scare liberals because…we come from a background where we’re not supposed to be this way. We’re supposed to be dependent and…be a part of this twenty-first-century plantation that they created back in the late 1960s and 70s.”

It’s this racial frisson that gives the Cain candidacy electricity. If Herman Cain were white, how far might his record as a pizza CEO take him? He’d be Mitt Romney without being able to claim a single political victory or time in public office, or a health care plan to explain away. The black Herman Cain, however, is something else entirely; conservatives believe the black man ties liberals up in knots and drives them crazy. I doubt very much that Cain will actually win the nomination, but it bears remembering that after the Democrats nominated and the voters elected a black president, the GOP named a black chairman, Michael Steele, even though he’d never been more than a lieutenant governor of a state a Republican presidential candidate will almost never win (Maryland) and was widely seen as a buffoon. Since Steele’s departure from the national stage, we have seen the rise of the Tea Party groups, a nearly all-white movement that voices loud objections when accused of racism. The urge to say “See! We’re not racists!” is not to be underestimated. Nor is the equally strong desire to traduce liberals and the media. Both help explain Cain’s surge and continued appeal, even in the face of the allegations about sexual harassment and a string of gaffes.

How Cain came to his ultra-conservative views is worth consideration, although he is disappointingly oblique about this in his book (he did write another book in 2005, They Think You’re Stupid, about the Democratic Party, which goes into more detail about standard conservative policies than personal history). Race appears to be central, and specifically his own perception of how he overcame barriers. One often hears black conservatives say in one form or another that they were not about to let their race hold them back, that they asked for no favors, only the opportunity to prove themselves, which they received. His father, Luther Cain, “never allowed his starting point in life or the racial conditions of his time to be excuses for failing to pursue his dreams,” and he instilled in his son those same values.

Conservatives say things like that all the time, often with a whiff of self-righteousness, as if they are boldly challenging received liberal opinion. But of course there is nothing that is inherently conservative in such views. Barack Obama, Bill Cosby, Oprah Winfrey, and any number of prominent African-American liberals believed and were taught many of the same things growing up.

The difference between the two is that while Obama and liberals generally sense a great debt to the civil rights pioneers who made their opportunities possible, Cain and other conservatives generally tend to persuade themselves that they have done it on their own. Cain was a teenager, living in the same town as Martin Luther King Jr. when King was rising to national prominence. He was a ten-year-old boy when King first gained fame in 1956, and a teenager throughout the tumultuous early 1960s. He must have been aware of what was happening around him. But he writes of the movement only briefly and remotely:

I was too young to participate when they first started the Freedom Rides, and the sit-ins. So on a day-to-day basis, it didn’t have an impact. I just kept going to school, doing what I was supposed to do, and stayed out of trouble—I didn’t go downtown and try to participate in sit-ins.

And that is that: because he had no direct involvement in the movement, he assigns it no meaning in his life. It’s a view that’s reflected in the Tea Party ideology, the idea that people have made it entirely on their own without asking for any handouts, and they don’t want “government” in their lives now. This is the story Cain has decided to tell himself about himself. And when he did encounter racism, like the time he went to get a haircut in Fredericksburg, Virginia, but was told the shop would not accept blacks, he vanquished it by reminding himself to behave like a you-know-what: “When I left that barbershop, I bought a set of clippers and cut my own hair. I continue to cut my own hair to this day, exercising my right as CEO of Self to do so.”

Cain appears not to have been especially political until the 1990s, when he won some notoriety among conservatives for confronting Bill Clinton at a public forum on health care, arguing to the President that new costs associated with the proposed changes would force him to lay off employees. He was the CEO of Godfather’s Pizza during this period, learning that the surest way to test the quality of a pizza was to order the all-meat pie: “If it tastes too salty, I know that the meat is not top quality.” (Cain recently told GQ that pizzas piled high with meats are “manly,” while vegetable toppings make for “sissy pizza”). He joined the board of the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank and became its chairman in 1995 and 1996—the most impressive item on his résumé.

He left Godfather’s that year and came to Washington to head the National Restaurant Association, the chief lobbying arm of the restaurant industry, representing 380,000 high-end eateries, fast-food joints, suppliers, and other related businesses. The book devotes only about one quick page to this phase of his career, the period during which he is alleged to have harassed as many as five women. By 2000, he moved back to Atlanta, to concentrate on his “keynote-speaking and leadership consulting company,” T.H.E., Inc. (it stands for The Hermanator Experience) and to start a talk-radio show.

He ran for the Senate in 2004, for the seat of the retiring Zell Miller, finishing second in the GOP primary. He began working with Americans for Prosperity (AFP), the Koch brothers–funded group involved with a variety of right-wing lobbying and grassroots activities. He then had to contend with cancer in 2006, after which he went back to talk radio.

The Cain–AFP relationship is mysterious—for example, it is not clear whether Cain was an actual employee. An AFP spokesman told The New Yorker’s Jane Mayer only that Cain has “spoken at our events sometimes without charge, and other times we might pick up travel expenses or give a modest honorarium.”2 At the least, the relationship appears to have enabled Cain to speak to conservative audiences across the country for a number of years. Cain’s campaign manager, Mark Block, is the former head of the Wisconsin AFP chapter. So there is good reason to think the Koch brothers view his candidacy favorably, a kindness Cain reciprocated at a recent conservative event by affirming, to the rapturous delight of the audience, that “I am the Koch brothers’ brother from another mother.”

In a field of extremists, Cain is as far out as anyone. His “9-9-9” tax plan would be a bonanza for the wealthiest taxpayers and would hit middle-income and poor people hardest. The Brookings Institution’s Tax Policy Center found that the plan would raise taxes on 84 percent of US households, by higher percentages the further down the income scale one goes. Meanwhile, households with more than $1 million in annual earnings would see their tax bills cut in half. Capital gains, under Cain’s proposal, would be completely tax-free. The 9-9-9 plan makes George Bush’s 2000 campaign proposal, which lowered rates on the highest earners the most but at least lowered rates for everyone, seem egalitarian.

Cain was also one of two GOP candidates at a November 12 forum to declare outright that waterboarding is not torture (the other was Michele Bachmann). In This Is Herman Cain!, the only foreign policy issue that gets him really worked up is Israel. He excoriates Obama on the topic as on almost no other, and he avows that the “Cain Doctrine” will hold that “if you mess with Israel, you’re messing with the United States of America. Is that clear?”

His extremism is combined with a plain ignorance that pops up from time to time. His November 14 stumble on Libya in a meeting with The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel is worth quoting. Cain was asked simply whether he agreed or disagreed with Obama’s Libya policy, producing this un–CEO of Self moment:

OK, Libya. [Ten-second pause] President Obama supported the uprising, correct? President Obama called for the removal of Qaddafi. Just want to make sure we’re talking about the same thing before I say, “yes I agree,” or “no I didn’t agree.” I do not agree with the way he handled it for the following reason—nope, that’s a different one. [Ten-second pause] I gotta go back to, see…. Got all this stuff twirling around in my head. Specifically, what are you asking me, did I agree or not disagree with Obama on?…

Here’s what I would have—I would have done a better job of determining who the opposition is and I’m sure that our intelligence people have some of that information. Based upon who made up that opposition, okay, based upon who made up that opposition, might have caused me to make some different decisions about how we participated.

There was yet one more confused paragraph. Lurking behind these tangled remarks there may have been some pertinent questions: Just what groups, with what ideologies, and what motives, did the Obama administration support, and were they the ones most likely to run a workable democracy? But Cain fell far short of stating the problem or showing he had adequate information about it. His later explanation was true to form:

I call it flyspecking every word, every phrase, and now they are flyspecking my pauses, but I guess since they can’t legitimately attack my ideas, they will attack words and pauses. I’m kind of flattered that my pauses are so important that somebody wants to make a story out of it.

At the November 22 debate on foreign policy, Cain barely registered a pulse; all the old bravado was gone, so nervous was he about making another faux pas.

A clever and credible second-tier candidate who rises to the top through a series of unexpected fortuities, as Cain did in October, recognizes his good fortune and tries to capitalize on it. That might have been the time, for example, for Cain to schedule a major address, on foreign policy, say, attracting some establishment Republican mandarins who would be willing to vouch for the candidate’s character and seriousness of purpose to stand at his side. But the Cain operation didn’t think to do this sort of thing.

The political press ascribes such failures to Cain’s inexperience, but his real problem is his vanity. An accurate assessment of his rise would have attributed it to conservative voters’ distrust of Mitt Romney first and foremost, and their looking to Cain for some of the reasons that have been noted here. But This Is Herman Cain! persuades me that the candidate saw his ascendance as inevitable, an electorate finally but merely coming to its senses. So he didn’t think he had to do anything more to close the deal. All those burgers hawked, all those manly pizzas peddled, all those millions banked; and yet, at the one moment in his life when he needed discipline the most, the CEO of Self crumpled.

—November 23, 2011

Postscript, November 30: Whatever slim chances Cain had at reviving his candidacy in time for the caucuses and primaries seemed to disappear completely on November 28, when the Atlanta Fox News affiliate broke the story that a woman named Ginger White was alleging publicly that she and Cain had a thirteen-year affair—a relationship, she said, that he cut off just recently, right before he started running for president. The woman showed the Fox reporter cell phone bills with sixty-one calls or text messages from a number that she said was Cain’s. The reporter texted the number, and Cain himself called back. True to form, Cain denied everything. He acknowledged knowing White but said he was merely “trying to help her financially.”

White’s most interesting remarks, though, were not about sex, and they support the assertion that Cain’s core problem is not ineptitude but a vanity that has somehow insulated him from thinking that such mud could ever be slung in his direction. In explaining to the reporter that Cain never harassed her and always treated her well, she noted that the Cain she knew was “very much the same” as the Cain seen on the campaign trail: “very much confident, very much sure of himself. Very arrogant in a playful sometimes way. Very, ah—Herman Cain loves Herman Cain.”

This Issue

December 22, 2011

Strauss-Kahn: The Untold Story

The Crass, Beautiful Eternal City

-

1

Cain’s response to the sexual allegations has not been limited to playing to conservative voters’ emotions. He hired an aggressive Atlanta lawyer, Lin Wood, who told the Atlanta Journal- Constitution on November 8 that “I’m not here to scare anyone off,” but women considering coming forward with allegations against Cain should “think twice, anyway.” The campaign has also established a website, www.caintruth.com, which posts items from the political press tending to exonerate Cain and raise questions about his accusers. ↩

-

2

See Jane Mayer, “Herman Cain and the Kochs,” www.newyorker.com, October 20, 2011. ↩