In his acute, prolix study of contemporary book-publishing practice in the United States and Great Britain, John B. Thompson, a British sociologist, warns against drawing facile inferences from digital technology. He writes:

The fact that ebook sales finally [came] to life…when the sales of traditional printed books were declining is only [a] superficial…sign—we are still a long way from [when] publishers can rely on ebook sales for a substantial or even a significant proportion of their revenue (if indeed they ever will).

But what if digital technology spawns a radically new mode of distribution with few of the present industry’s fixed costs, one that delivers content in both physical and e-book form directly to readers wherever they may be?

How this new mode of production will affect the world’s future as Gutenberg’s press unexpectedly affected the future of Europe is not within the scope of Thompson’s book. Even at this early stage, however, we may safely assume that this historic change, like all human ventures, will not be an unmixed blessing. We may be thrilled to know that Su Tung Po, Mark Twain, and Leo Tolstoy can soon be read in multiple languages by residents of the most remote human settlements but Das Kapital and The Fountainhead are also books and they and their digital successors will now enjoy greater access than before to susceptible readers.

Digital enthusiasts should also consider that as the embrace of other electronic media has widened, the average quality of their product has declined: from Masterpiece Theatre to Jersey Shore, from Franklin Roosevelt and Adlai Stevenson to Sarah Palin, from Julia Child to Rachael Ray. My own guess is that the digital future in which anyone can become a published writer will separate along the usual two paths, a narrow path toward more multilingual variety, specificity, and higher average quality and a broader path downward toward greater banality and incoherence, while the collective wisdom of the species, the infallible critic, will continue to preserve what is essential and over time discard the rest.

Electronic storage is fragile and interconnected, subject to unpredictable shocks, corruption, and deletions including those instigated by dictatorial regimes and individual lunatics. The two-thousand-year-old codex—printed pages, bound between covers—therefore will not go the way of vinyl and the compact disc but will survive for content worth keeping while the e-book/ e-pad formats and their future iterations will be more and more widely used, particularly for ephemera including soft-core pornography by women,1 the fastest-growing e-book category, and most reference works, such as encyclopedias, atlases, manuals, and so on that are constantly revised and may now be downloaded item by item.

Far more than any other medium, books contain civilizations, the ongoing conversation between present and past. Without this conversation we are lost. But books are also a business, which is the subject of Thompson’s book. As a social scientist he studies the “field” of book publishing as he would that of a strange culture. He has “listened attentively to people speaking a language [he] didn’t understand [and] eventually grasp[ed] the rules of grammar that make their language intelligible…[to] one another.” From this he “reconstruct[s] the logic of the [book publishing] field.” Like Samoan teenagers affronted by Margaret Mead’s version of their ritual coming of age,2 Thompson’s subjects may resent what an outsider has made of their own practices, but the wiser among them will be impressed, for this is the story of a culture in trouble, facing a profound change in its mode of production, but so encumbered by its past as to be unable to seize opportunities offered by technological change.

Had Thompson begun his book with its conclusion and described the culture of publishing in transition toward a digital future, he might have told a more dramatic story. Instead he has produced a fine-grained snapshot, frozen in time, of the terminal struggle of traditional publishers. His mordant picture of an industry in crisis gives publishers, writers, and readers much to think about.

The industry that Thompson has studied, to say nothing of the digital future that he belatedly describes, could not have been imagined fifty-two years ago when I first joined Random House as an editor. Then the cultivation of the backlist was essential to publishers’ survival, a mark of distinction and a service to civilization. We took pride in our brilliant backlist and weighed every editorial decision with backlist in mind. If a strong preliminary sale was also in prospect, so much the better, but it was backlist income that had sustained the highly conservative publishing industry for centuries and would do so forever, we thought then.3

Advertisement

Random House editors were entrusted with all but unlimited autonomy. There were eight or nine of us of more or less equal status in those years, supported by editorial assistants and a small technical staff: a publicist, a sales manager responsible for a dozen or so travelers, a production manager, an art director, a business manager, copy editors, a receptionist, a telephone operator, a few warehouse people, and the founders, who shared a secretary. They looked after large matters and left editorial decisions to the editors except where unusual risk was involved. The internal telephone directory didn’t fill a three-by-five card. Best sellers were welcome but not, as they are today, a matter of life and death. Random House best sellers typically enjoyed a long second life on our paperbound backlists, which were stocked by hundreds of independent bookstores in cities and towns. Our procedures were informal. We had no meetings.

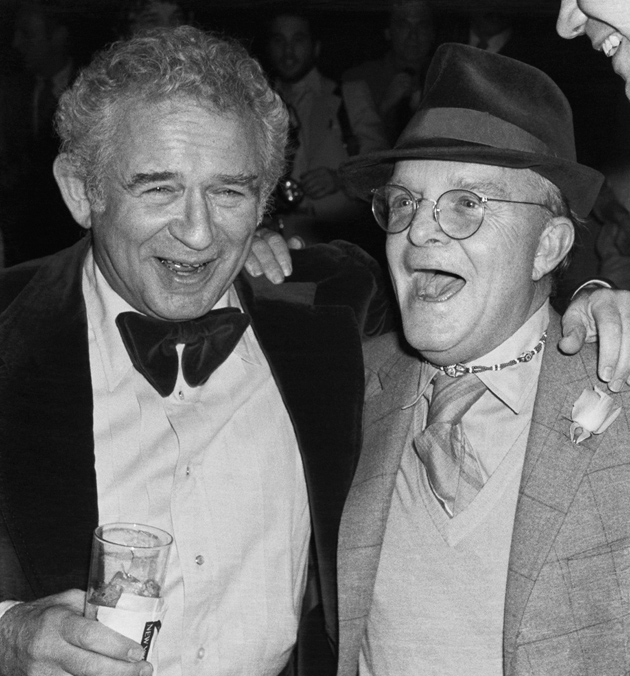

Unlike today’s market, dominated by a few national chains, most bookshops were locally owned and managed. Their staffs were usually avid readers and knew what to recommend to their customers. Many of them were our friends and confidants, keeping us in touch with the marketplace. Mornings I stopped at the basement mail room to read the day’s orders before I walked upstairs to my office. Random House was a happy and successful place, a dream in retrospect populated by William Faulkner, Jane Jacobs, Bill Styron, Ted Geisel, John O’Hara, Jim Michener, Robert Penn Warren—where the owners kept their business worries to themselves while we spent our days and nights with Wystan, Toni, Jim, Edgar, Truman, Norman, Terry, Red, and Peter. The company made money but this was a means, not an end. What mattered most to us was the work itself. The business grew and survived the occasional drought. We thought it would never end.

And then it ended. When I joined the company in 1958 its sales were less than $8 million. Because the business was privately owned, none of us knew or cared what it was worth until the owners took the company public to establish a valuation for estate-planning purposes. Then, having acquired a few smaller firms, including the illustrious Alfred A. Knopf, the owners, thinking of retirement, sold Random House to RCA in 1965 for $40 million, a surprisingly high figure.

We assumed that RCA, which owned one of the great music labels, had been impressed by Random’s equally distinguished backlist. RCA was acquired in turn by General Electric, which had no use amid its jet engines, locomotives, and dynamos for a marginally profitable player in an exotic field and sold the company to Condé Nast. Eventually Random House, by now laden with acquisitions, was acquired by Bertelsmann, a German conglomerate, for $1 billion, more or less, an astonishing price in 1998 for a mature firm in a marginal industry. By then the Random House I had known was unrecognizable.

The trouble had begun in the Eighties when the book business had unexpectedly inverted, the result of the demographic shift from cities to suburbs in which the large, urban, independent bookstores with extensive backlist stocks and bookish owners and clerks attuned to their customers’ tastes and interests began to disappear as their customers migrated to the suburbs. They were replaced by chains of small shops in malls, paying the same rent as the shoe store next door and dependent on the same turnover. The effect on Random House was felt as a loss of autonomy as our retail market consolidated under remote management. The chains borrowed their business plan from McDonald’s. Books were hamburgers, fast-moving items with mass appeal served by unsophisticated staff to anonymous customers. Their management thought of books as units and no longer talked to editors.

As backlists melted away, best sellers were now essential to publishers’ survival: a disaster for undercapitalized publishers and a bonanza for agents of brand-name authors who could now put their celebrity clients up for auction, forcing publishers to risk ever greater guarantees to sustain a constant supply of potential best sellers demanded by the malls. Only the richest houses could afford the shortfall when these guarantees failed to earn out and truckloads of unsold copies were returned to the warehouse.

Since size was now obligatory, mergers and further mergers were inevitable. The result is today’s ramshackle conglomerates with their ghostly imprints served by layers of costly management unable to respond nimbly if at all to an expanding digital marketplace in which the major innovations are introduced not by publishers but by the electronic marketplace itself—by Google, Amazon, Apple—to which publishers have only belatedly and weakly responded.

In the mid-Eighties I proposed to my colleagues at Random House that we create a direct mail catalog comprising 40,000 or so backlist titles selected from the lists of all publishers, to be ordered by readers over an 800 number. The Internet had not then been commercialized but digitization was in the wind and “disintermediation” had become a buzz word. I argued that with retailers increasingly unable to stock extensive backlist we should now sell our backlists to readers directly. I was, of course, proposing the opportunity that Amazon eventually seized. My colleagues rejected the idea for fear of offending our retailers, and perhaps because intermingled backlists suggested unseemly intimacy among competitors, reasonable objections at the time and a textbook example of how existing infrastructure paralyzes innovation.

Advertisement

Technological change is discontinuous. The monks in their scriptoria did not invent the printing press, horse breeders did not invent the motorcar, and the music industry did not invent the iPod or launch iTunes. Early in the new century book publishers, confined within their history and outflanked by unencumbered digital innovators, missed yet another critical opportunity, seized once again by Amazon, this time to build their own universal digital catalog, serving e-book users directly and on their own terms while collecting the names, e-mail addresses, and preferences of their customers. This strategic error will have large consequences.4

Meanwhile the conglomerates, managing dozens of imprints and publishing thousands of new titles a year, are increasingly alienated at the managerial level from their commoditized product. Thompson lets a typical sales manager describe the bloody triage by which so-called “big titles” are singled out and presented to chain store buyers:

Each day of the sales conference we’ll have a session with a core publisher from one of the groups. They [sic] come into a conference room, we show covers and so on. Let’s say the summer list will be 2,000 titles. We have our meetings and first of all, we don’t cover…all their titles. So if the total number is 2,000 [we] will cover, say, 1,500. Then what I do is sit down with my divisional directors, we take the 1,500 and I come up with what we call our “priority” titles [those that can be presented to the chain store buyers], and that’s going to be about 500.

Since the chain store buyers cannot respond to an entire season’s output from all publishers, further triage takes place at their level.

Thompson writes:

There are many industry insiders who have long had doubts about…some of the practices that have come to define the field—the competitive auctions [to acquire books] that ratchet up the stakes to levels far in excess of what most books are likely to earn, the shipping out of large numbers of books followed by the almost inevitable wave of returns, the high premiums paid by publishers…to get their books stocked and displayed in the major retail outlets, the relentless drive for levels of growth that are unsustainable in the long run.

All contribute to the existential angst that marks today’s industry at all levels.

The few large chains that publishers depend on for most of their sales are themselves in trouble as their growth slows and more aggressive discounters than themselves preempt the larger part of the best-seller trade while Amazon captures most of the backlist and e-book business. Like the conglomerates, the retail chains have also been shaped by forces beyond their control. By the mid-Eighties the mall-based chains had begun to reach their limits of growth as new locations became marginal. A new retail format emerged, so-called freestanding superstores inspired perhaps by the remarkable success of the Tattered Cover, a 40,000-square-foot Denver bookstore with deep, well-chosen inventory in every conceivable category, brilliantly staffed and managed, and by the equally well run original Borders in Ann Arbor (which Thompson incorrectly describes as a small shop), with its own vast inventory chastely displayed spine out in keeping with its academic setting.

As these superstore chains evolved, however, they resembled not the exquisitely stocked Tattered Cover and the original Borders, which defiantly shelved even current best sellers spine out and alphabetically, but larger versions of the mall stores, emphasizing high-volume turnover of current best sellers and high-margin remainders while sophisticated backlist inventories, despite the best intentions of management, languished. This was not what the superstore executives had hoped for when they launched their new retail format and filled their shelves with deep backlist inventory only to return much of it a few years later as unsalable by inexperienced clerks in inappropriate locations. Since the Denver and Ann Arbor originals could not be replicated as national chains, the pressure upon publishers to produce “big books” increased accordingly.

Except in the case of established brand-name authors—but not always even in their case—“big books” often fail to meet expectations. Many are artifacts of contagious enthusiasm or “buzz,” what Thompson in his social scientist mode calls the ritual. He writes that there is “a web of collective belief.” Since “no one really knows” how well new titles will do, much effort is invested to persuade people that a book is sufficiently big to warrant serious attention and “a great deal of weight is placed on what other people…think and say”:

Big books…are social constructions that emerge out of…the chatter…among players in the field…. In the absence of anything solid, nothing is more persuasive than the expressed enthusiasm (or lack of it) of trusted others,…and the more that excitement is backed up with…hard cash, the more likely it is that others will become excited by it. This is the contagion effect in the field of trade publishing, and it is hard for those involved in the field, even those on the margins…, not to be seduced by…

this ritual potlatch, the technical term for this behavior which Thompson may be too polite to use. Despite this irrationality writers continue to submit and editors continue to publish season after season the normal quota of distinguished books, which readers buy and read as they always have. That this ancient activity survives under difficult conditions testifies to the persistence of storytelling as an indispensable human activity, one that has outlived far worse hazards—the burning of the library at Alexandria, the bonfires of Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and others—than the bizarre procedures that Thompson describes.

Today’s publishing industry, including its major retailers, did not incur these distortions by rational choice but by adapting under pressure to external conditions, while the industry’s mainly passive response to the rise of digital technology over the past quarter-century has blocked innovation. Should the retail market deteriorate further, publishers may at last be forced to heed the digital imperative, consolidate their lists, and sell directly to consumers. Some publishers may experiment by setting up their own freestanding digital start-ups but my guess is that a separate, self-financed, digital industry will coexist with and over time replace many functions of the traditional firms as the logic and the economies of digital technology increasingly assert themselves. For example the rapidly growing self-publishing industry, relying on print-on-demand technology, has created infrastructure5 that groups of sophisticated editors might adapt to create their own lists for worldwide sale online while arranging with traditional distributors to market physical inventory to traditional retail accounts.

I like to think that these digital start-ups, whatever form they may actually take, will resemble the Random House of fond memory. Since start-up costs will be low these firms may be owned and operated by like-minded editors taking advantage of the Web to develop niche markets for titles reflecting their shared interests and expertise: new fiction, trout farming, Lincolniana, stem cell research, ballet, Cleopatra, and so on. These digital start-ups will promote and distribute their specialized titles on appropriate websites to readers with similar interests, capturing their names and e-mail addresses to form communities of interest linked to similar communities worldwide.

Authors’ advances may be financed by outside investors as films are sometimes financed or through profit-sharing deals with authors and agents acting as business managers. Routine publishing functions can be outsourced. Digital staff need not occupy the same rooms or even the same city or country. They will incur no inventory or delivery expense, no returned inventory, and will sell directly to end users who may access files to be read on screens or on handheld devices or printed one copy at a time on demand locally, as self-published books are already being printed to order at worldwide sites.

The marketplace will be self-correcting. Well-regarded sites will flourish while others fail. Files may also be posted to a vast multilingual directory of titles of the sort envisioned by Google perhaps in conjunction with the Library of Congress and other national libraries. A new, global copyright system is essential: traditional territorial boundaries are obsolete and authors must be paid for their work. Books have always been sold chiefly by word of mouth, for which the Web, with its multiple links to social networks of many kinds in many languages, has become a heretofore unimaginably powerful sales medium. Bookstores and libraries will survive as storytelling centers have existed for aeons, reflecting the human need for shared, vicarious experience, but now they will have access digitally to millions of books in many languages. Bookstores and libraries, whatever their eventual form, may also become publishing centers using linked print-on-demand technology.

Thompson writes:

Whatever happens, it seems to me likely that the book, both in its traditional printed form and in those electronic formats that turn out to be sufficiently attractive to readers…, will continue to play an important role…in our cultural and public life…. Books [are] a privileged form of communication, one in which the genius of the written word can be inscribed in an object that is at once a medium of expression, a means of communication and a work of art.

For the telling of extended stories…or the sustained interrogation of our ways of thinking and acting, the book has proven to be a most satisfying and resilient cultural form, and it is not likely to disappear soon. [But] the basic structures and dynamics that have come to characterize the world of trade publishing [will be] shaken up in new and unexpected ways.

How books will be produced and delivered, who will do what and how they will do it, what roles the traditional publishers will play (if any) and where books will fit in the new symbolic and information environments that will emerge in the years to come—these are questions to which there are, at present, no clear answers.

But there are ways to think about the digital future and Professor Thompson’s survey of the current situation provides a good place to begin.

This Issue

February 10, 2011

-

1

The New York Times, December 8, 2010. ↩

-

2

Coming of Age in Samoa (Morrow, 1928). ↩

-

3

2011 marks the fiftieth anniversary of Random’s publication of Jane Jacobs’s highly influential The Death and Life of Great American Cities, still in print after half a century. The author’s guarantee was $2,500. Its first printing was 7,500 copies. ↩

-

4

Several large publishers have tried to recover some of this lost ground by adopting the so-called agency model, in which the publisher retains ownership and sets the price of its files while the distributor receives a sales commission, a strategy meant to overcome the legal restriction that retailers are entitled to set the price of goods they buy from a manufacturer, and to thwart Amazon’s costly attempt to establish an industry standard by creating an artificially low consumer price for e-books, hoping that publishers will adjust their price to Amazon accordingly. As of this writing the pricing future is unclear. To add to the confusion, publishers are themselves only licensees selling content that belongs to their authors, represented by agents determined to increase their share of this complex pudding. Meanwhile online distributors retain exclusive access to customer data. In the digital future authors in partnership with publishers and advised by agents may simplify matters by selling their content directly to end users over appropriate websites. ↩

-

5

Self-publishing has an illustrious history. Milton published Areopagitica himself and Whitman self-published the first edition of Leaves of Grass. When he could not find a publisher for his first novel, Maggie, a Girl of the Streets, Stephen Crane published it himself. James Joyce in similar circumstances published Ulysses with the help of Sylvia Beach and her Shakespeare and Company bookshop. The Joy of Cooking was first published by its author and so were such recent best sellers as Richard Evans’s Christmas Box and Tom Peters’s In Search of Excellence. ↩