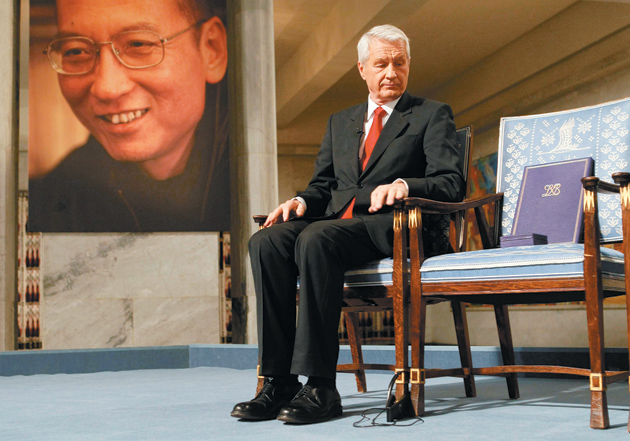

Heiko Junge/AFP/Getty Images

Nobel Committee Chairman Thorbjørn Jagland looking at the empty chair reserved for the Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, December 10, 2010. According to news reports, since the award ceremony, the Chinese words for ‘empty chair’ have been banned on the Chinese Internet and some bloggers who have used the phrase or posted images of empty chairs have had their sites blocked.

I.

Each year around the “sensitive” anniversary of the Beijing massacre of June 4, 1989, Ding Zilin, a seventy-four-year-old retired professor of philosophy, is accompanied by a group of plainclothes police whenever she leaves her apartment to go buy vegetables, or to do anything else. Her son, Jiang Jielian, was killed in the massacre by a bullet in the back, and very soon thereafter Ding decided—unlike other parents who had lost children—to defy the government’s demand that the families of victims keep quiet and absorb their losses in private. She organized a group called “Tiananmen Mothers” and, in her speaking and writing ever since, has essentially said to the regime: say what you like, and do what you will, but my mind belongs to me and you cannot have it. (In October, the Tiananmen Mothers called on the Chinese government to release Liu Xiaobo, the imprisoned writer who was awarded the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize and who has been a longtime supporter of the group’s efforts.) Václav Havel, whom Professor Ding admires, called this “living in truth.” To the regime, it makes Ding a dangerous person.

Many people have wondered where Ding Zilin got the mental fortitude to confront a vast and potentially brutal government. Even more worth probing, in my view, is what the standoff says about the mentality of her opposition. The Chinese government is the largest in the world. It commands more soldiers than any other government, and owns about $2.5 trillion—by far the most in the world—in foreign exchange reserves. It is widely viewed as an emerging superpower. Nevertheless it sends plainclothes police to accompany a seventy-four-year-old woman as she sets out to buy vegetables. Why? The two books under review here do not have all of the answers to this question, but they illuminate it in profound ways.

Today’s “rising China,” which from the outside can seem to exude strength and confidence, inwardly lives with an unsure view of itself. People sense, even if they do not want to talk about it, that their country’s current system is grounded partly in fraud, cannot be relied upon to treat people fairly, and might not hold up. Insecurity, the new national mood, extends from laid-off migrant laborers to the men at the top of the Communist Party. The socialist slogans that the government touts are widely seen as mere panoply that covers a lawless crony capitalism in which officials themselves are primary players. This incongruity has been in place for many years and no longer fools anyone. People take it as normal, but that very normality makes cynicism the public ideology. Many people turn to materialism—whether in property or investment—in search of value, but often cannot feel secure there, either; even if they gain a bit of wealth, they do not know when it might disappear or be wrested away.

One stopgap that top leaders have used has been to stoke national pride. They have staged an Olympics and a World’s Fair. They arrange to broadcast throughout China that the Dalai Lama is a “wolf” who would “split the motherland.” Such tactics have had some success. Chauvinist sentiment, especially among the upwardly mobile urban young, is easy to provoke, and is sometimes loudly expressed.

Yet in quieter settings, Chinese people continue to make decisions that reflect their lack of confidence in China’s future. Farmers from Fujian province still pay “snakeheads” tens of thousands of dollars to smuggle one person to Sydney, London, or New York. Of the approximately 145,000 Chinese students who go abroad each year for study, only about 25–30 percent return to live in China (and of these, some keep foreign passports tucked away). Even leaders of the Communist Party send their children—and large amounts of their money—to places like Vancouver and Los Angeles. An elderly man in Hu Fayun’s novel Ruyan@sars.come observes that

here [in China], who knows when all hell might break loose, leaving no place to hide?… Everyone feels this at a certain level but doesn’t say so. Why else would the people who hold all the power in our society be sending their sons and daughters abroad?

Can the problems be solved? What does China need today? Yang Jisheng, author of the nonfictional Mubei, or Tombstone, has written a different sort of book from Hu Fayun’s, but the two authors share a conviction that what China most needs is an honest look at its past, and especially at the record of where it has been during sixty years of Communist rule. China’s rulers, who fear the consequences of such retrospection, have been assiduous in seeking to prevent it. Shortly after Hu’s novel appeared on the Internet in 2004, the authorities closed down the website that carried it. But the text, which was loose in cyberspace, continued to spread anyway. In 2006 authorities allowed the novel to be published in book form after cutting out many politically “sensitive” passages. Yang Jisheng, in trying to publish Mubei, got nowhere with publishers inside China and so turned to Hong Kong. The Hong Kong book was barred from the mainland, but spread electronically and eventually appeared on the mainland in an underground pirated edition.1

Advertisement

Mubei is about the Great Famine of 1959–1962, the story of which, in outline, has been well known for some time. Mao Zedong, wanting China to “surpass England and catch up with America” within fifteen years, and pursuing utopian transformation of the Chinese countryside at the same time, calculated that a sudden boom in grain production could support new industry as well as provide exports that would pay for Soviet technology. A radical reorganization of the Chinese countryside ensued. Family farms were abolished in favor of large “people’s communes.” The state appropriated tools, draft animals, and all land. It controlled marketing and set impossibly high “production quotas.”

One reason quotas were too high was that Mao relied on the teachings of the Soviet agronomist Trofim Lysenko, who claimed that rice seedlings could be planted without separating them and that, to cite just one of many other examples, pumpkins could be crossed with tomatoes in order to produce giant tomatoes. Chinese farmers knew such ideas to be nonsense but were in no position to disobey. As a result grain production plummeted at the same time that reported harvests soared. (They could not but soar; the Great Leader had said that they would.) Frightened officials, under pressure to meet and even “overfulfill” their quotas, gathered whatever grain they could find and shipped it to the cities. Peasants who balked at handing over their last stores could be charged with “hoarding,” which was a serious crime. Within three years, between 20 and 40 million people died. Only World War II has taken a larger toll in modern times.

What Yang Jisheng adds to this picture is comprehensive scope and authoritative detail in overwhelming amount. When he began research for the book in the early 1990s, he was already a prizewinning senior reporter with the official New China News Agency, a status that allowed him access to archives that were closed to others. He approached his work quietly, in order to avoid suspicion.2 He was able, in the end, to specify such things as exactly how much grain was held in public granaries at the height of the famine (about 22 million tons); how reports of the famine went up the bureaucracy only to be ignored at the top; and how authorities ordered the destruction of statistics in regions where population decline became evident.

Yang records how starving people ate tree bark, weeds, bird droppings, and flesh that had been cut from dead bodies, sometimes of their own family members; how they wandered into neighboring counties in search of food, only to find adjacent areas equally destitute, and then, when caught, found themselves charged as “criminal fugitives,” deniers of the truth that “there is no famine.” Punishments for this kind of offense included public humiliation, plus flogging. Parents who left their children at roadsides, hoping that perhaps a stranger might save them, were accused of “assaulting the Party.” As the famine worsened corpses became more visible at roadsides. There was no problem of dogs eating the corpses, Yang notes, because humans had long since eaten all the dogs—and toads, and lizards, and rats. People learned not to kill rats immediately; it was better to tie a string to a rat’s leg, follow it to its hole, and kill it then. That way one could eat the rat as well as dig down into its hole to recover whatever grain it might have stored below.

Police guarded county bus stations to prevent people from fleeing. Sometimes entire villages were put under lockdown. In the archives of local post offices, Yang found personal letters that had been confiscated during the famine because they had “cast aspersions on the excellent situation.” And where was all the resistance coming from? It came, said Mao, because “the democratic revolution has not been thorough enough.” “Right deviationists” needed to be punished, and the punishments needed to be public in order to warn others. Yang lists cases of people buried alive or suspended from beams in commune mess halls, and cites countless examples of the severing of ears. Some punishments acquired ghastly sobriquets. To strip a person bare, tie his hands, string him from a beam, wrap him in cloth, douse the cloth in oil, and set it afire was “lighting the celestial lantern.” To bury a living person with the shaved head exposed, then smash the skull to splatter the brain, was “opening the flower.” At times it is hard to read Yang. You have to set the book down, take a break, and come back later. This review omits the most difficult examples.

Advertisement

The main reason why the Great Famine continues to haunt China fifty years after it happened is that people are obliged—forcibly, if necessary—to continue to accord the famine’s primary perpetrator, Mao Zedong, a position of honor. Mao’s portrait still hangs at the center of Tiananmen, where it overlooks his embalmed body, which lies supine in his mausoleum within the giant square. And Mao remains the spiritual godfather of today’s regime.

Today’s Chinese textbooks and museums omit mention of the famine (noting, at most, “three years of difficulty” caused by “bad weather”), and young Chinese sometimes express the view that vague stories of a famine must be the fabrications of foreigners. Still, many people remember. Inside families that experienced the famine, word passes from generation to generation. What remains largely unknown is how widespread the famine was. People who know that their own family or village suffered terribly may not know that as many as 36 million (Yang Jisheng’s figure) died in other places. If that fact were well known in China, the consequences for Communist Party rule would be severe. The Party’s ban on Yang’s book is not irrational.

Hu Fayun’s novel, written in a fluid and graceful style, also looks at the past, at “unofficial history that is not in the textbooks,” and addresses the famine as well as a wide range of other issues: the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the Cultural Revolution, corruption, censorship, the massacre near Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989, the SARS epidemic, illegal detention centers, and much else. It also evokes the materialism, cynicism, and narrow nationalism of the current day. An underlying question of “how can we make sense of China’s Communist experience as a whole?” ties the book together.

The story tells of Ru Yan, a middle-aged widow whose only son goes to study in France. He leaves her with a computer to help her stay in touch with him. The computer opens to her the world of the Internet, in which she finds unexpected joy and release. It seems to her “like gazing into the starry sky, vast and limitless”; she reflects that here, finally, is the Communist ideal of “to each according to his needs.” But it is not just the Internet’s cornucopian plenty that attracts her; even more important is the freedom that comes from online anonymity. Ru Yan works in a botany research institute, a “work unit” that dates from the Mao era, and the rule in such places, for decades, has been to bottle up your inner thoughts and feelings lest a “mistaken” comment be noted by coworkers and held against you. In cyberspace, exactly to the contrary, Ru Yan finds that people use pseudonyms and say whatever they want, with impunity. “No one sees anyone on the Web!” How liberating. She joins in.

She discovers a chat group of other parents who have children studying abroad. Then she meets a group who take political ideas seriously. After befriending these people online, she meets some of them in person. The political thinkers had begun, a few decades earlier, as “young Marxists.” Later, battered by Mao and alienated by post-Mao cynicism, they went their separate ways, and now are bound only by friendship. One works as a handyman, but writes trenchant political dissent on the Internet. One put aside idealism, studied law, and now makes a lot of money. One has chosen to become a fake intellectual: he writes books of elegant nonsense (“what I write is not what I think”), has joined the Party as a career move, and rises to high position in the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. When his lifelong friend the handyman confronts him about all of this, he admits that he is, indeed, “selling quack medicine,” but says he does it only because he wants a better life for his family. “And you?” he challenges the handyman. “Can you really save China? Those fancy ideals we used to have—what good are they, really?”

The handyman is shocked, but maintains their friendship. After all, beneath the disgusting cynicism there still survives a human being, someone who at least remembers what an ideal is and is aware of the choices he now is making. More worrisome, to the handyman, are the many people in China who lack even the capacity for conscious choice. He writes an essay on the topic of terror and what it does to people, how it was used in the Cultural Revolution, the Beijing massacre, and elsewhere, and has left zombies on the Chinese landscape:

Terror itself is nothing to laugh at. But there’s something even more fearful than terror, even harder to take, and that is to see how people end up once terror has passed…. Terror can be more powerful than killing. With killing, merely the body is destroyed; but terror can invade a person’s inner spirit, take over its space, and turn the most refractory rebel into an obedient slave—who then can serve as a model for a crowd of others. Most frightening of all is that terror lives deep inside you, where no one else can help you get rid of it.

The senior figure in the handyman’s group is Teacher Wei, a poet and literary critic who was purged in 1955, just before the arrival of the huge disasters of late Maoism. In hindsight Wei is grateful that he was sidelined early. “If I had had smooth sailing back then—had headed confidently in that [Maoist] direction—what might I have become?” He was crushed, though, when his wife left him without explanation, took their two small children with her and completely cut off contact. Only decades later does he learn that she did this to protect him from her own political taint (her family had had Kuomintang ties) and that eventually she, and one of their children, had been driven to suicide.

Wei’s life experience spans all sixty years of the People’s Republic of China, and it is primarily through his retrospection, and the questions that the younger people in the group ask him, that author Hu Fayun poses his book’s main question of “How do we make sense of it all?” Wei speaks brilliantly about the question of how Chinese memory and cultural expression, including even his own, despite his conscious wishes, have been colored by Maoist politics. He tells how he recently found himself humming a tune and then felt shock to realize that the lyrics were “lifting my head, I gaze at the Big Dipper; in my heart, I long for Mao Zedong.” As Wei explains to the group:

Even our own most personal emotional memories are soaked in an all-encompassing, all-pervading ideological culture…. Within a few decades, they took from us our ability to express suffering and sorrow. They took our ability to express love. What they gave us instead were fraudulent stand-ins…. Even today we do not have an authentic, untainted cultural vehicle with which to record our lives…. Other countries have it. Even the poorest and most backward countries have it. But the country with the largest population and the longest history on earth does not have it—you have to admit there is something horrifying about this. The long-term effect on our nation’s psyche is still something that no one can measure.

Wei fears that if anyone, indeed, has grasped this point, it may be China’s rulers:

This is why the regime is happy to see commercial performances by third-rate crooners from Hong Kong and Taiwan occupy China’s stages: it blocks out songs that might truly express people’s sufferings and hopes.

Ru Yan, the widow, had learned many years earlier, from her mother, how to write elegant essays in Chinese. Now she begins to post some on the Internet. A friend brings the essays, and then Ru Yan herself, to the attention of Liang Jinsheng, a widower who is looking for companionship in later life and who also happens to be vice-mayor of the city where Ru Yan lives. He courts her, and she is charmed. Liang is urbane, treats Ru Yan with punctilious courtesy, and is capable of spontaneity and sprightly humor as well. Personally they get along fine, but as time passes it becomes clear that the straightforward Ru Yan cannot fit into the official culture within which Liang moves. This same charming man, as an official, can lie smoothly, quietly accept bribes, calculate his moves in political infighting, and do it all within a special language-game. At one point he and Ru Yan have this exchange:

“Your generation is different from my father’s,” said Ru Yan, laughing.

“Huh?” he asked.

“What they said outside the house was the same as what they said at home,” she said.

“So you can see we’ve made progress,” he replied.

“Progress?” She was puzzled. “Two kinds of talk for inside the home and outside is progress?”

Liang gave a sly grin. “This…I’ll give you a special seminar on it someday. It’s complicated. But it’s not as bad as you make it sound.”

In the end, Liang himself comes to see that the match with Ru Yan will not work.

Part of the appeal of Hu Fayun’s novel to Chinese readers seems to have been Ru Yan’s very attractive character. In the frenzy of initial Internet comment on the novel, readers wrote that they adored Ru Yan for being “what China needs” and “the way a person should be.” Here, if we stand back for a moment, is some good news to balance all of the evidence for moral rootlessness in today’s China. A fictional character whose most apparent traits are modesty, integrity, and common decency has become a champion to readers. This may reflect, on the one hand, how scarce these simple virtues are in readers’ daily experiences; but it also shows the strong popular thirst to see precisely these kinds of values reemerge.

Does popular admiration for Ru Yan’s character have anything to do with why plainclothes police accompany Ding Zilin to buy vegetables? I think so. What would happen if, somehow, open rebellion were to break out in China? Or a domino effect of the kind that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union were to occur? If Chinese people were truly in a position to choose, how many would say yes, this political party has safeguarded our nation and protected our cherished values for sixty years, and we will stand up for it now, in its moment of crisis? Would the people who admire Ru Yan’s character say that? Would the people who remember the Great Famine say that? Would the people who cause “mass incidents” (the government’s euphemism for strikes, demonstrations, roadblocks, etc., the numbers of which have grown to hundreds of thousands in recent years) say that? Would even the beneficiaries of Party policies—the wealthy and well-connected—stick with the Party instead of heading for safety in places like Vancouver?

These questions may not be easy to answer, but the regime’s own answers to them are fairly clear: take nothing for granted, and keep the lid on tight. An online article published in June by the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences reveals that government spending on a relatively new budget category called “stability maintenance” (weiwen) has risen to 514 billion yuan annually, which is more than the government spends on health, education, or social welfare programs, and is second only to the 532 billion yuan that it spends on the military.3

“Stability maintenance” means monitoring people—petitioners, aggrieved workers, professors, religious believers, and many kinds of bloggers and tweeters on the Internet—in order to stop “trouble,” especially any unauthorized organization, before it gets started. In the last fifteen years a popular movement called “rights maintenance” (weiquan) has spread in China. The government cannot come out explicitly against “rights,” because that would cause too much loss of face. “Stability maintenance” is clearly its response. Even at the linguistic level, weiwen has been designed to counter weiquan.

Liu Binyan, China’s distinguished investigative journalist and a contributor to these pages, who died of cancer in New Jersey in 2005 after living sixteen years in exile from his homeland, was a lifelong advocate of rights for China’s common people. After his cremation his family wanted to send his ashes back to China for burial. This had been Liu’s wish, but could it be done? The family worried that even the ashes of a regime critic might be viewed as “destabilizing” and perhaps be confiscated. With careful planning and tight secrecy, the family got Liu’s ashes back to China, and got them buried. Then they asked the cemetery staff if they could erect a tombstone bearing the following words:

Here lies a Chinese person who did some things that were right for a person to do, and said some things that were right for a person to say.

Liu himself had chosen the words. The cemetery staff agreed, but returned a few days later to tell the family that those words could not go onto the tombstone. Their “superiors” had said no. Nothing but Liu’s name and dates could appear on the stone. The superiors offered no explanation, but it seems clear that fears of “instability” must have been the reason. (What if someone were to lay flowers? What if several people did? What if a group formed?…) After deliberation the family decided to withdraw its request for the inscription, bide its time, and hope for a day when the stone might be able to appear as it should. For now the stone remains blank. Inadequate as a monument to Liu, it stands, in another sense, as an astute comment on today’s Chinese government. How can one capture, in brief, the odd combination of visible power and inner weakness? This wordless stone, in the end, might say it best.

II.

On December 10, I attended the award ceremony in Oslo, Norway, for the Nobel Peace Prize, which the government of China had a few days earlier declared to be a “farce.” The recipient was a friend of mine, the Chinese scholar and essayist Liu Xiaobo, whom Oslo was now referring to as a laureate and Beijing as a “criminal” serving an eleven-year sentence for “incitement to subvert state power.”

Countries that have embassies in Oslo were invited to send representatives to the ceremony, but the Chinese government had aggressively called for a boycott. In the end, forty-five countries attended, but another nineteen—including Russia, Pakistan, Cuba, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Vietnam—chose to stay away. How much their decisions were motivated by sympathy for the Chinese government’s position and how much by pressure from China over matters of trade and diplomacy is impossible to measure. From the United States, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi attended, along with Representatives David Wu of Oregon and Chris Smith of New Jersey.

The ceremony was one of the most exquisite and moving public events I have ever witnessed. The presentation speech was made by Thorbjørn Jagland, the chairman of the prize committee, who is a former prime minister of Norway and now secretary-general of the Council of Europe. Only a few minutes into his speech, he said:

We regret that the Laureate is not present here today. He is in isolation in a prison in northeast China…. This fact alone shows that the award was necessary and appropriate.

When he had finished reading these words the audience of about a thousand people interrupted with applause. The applause continued for about thirty seconds and then, when it seemed that the time had come for it to recede, it suddenly took on a second life. It continued on and on, and then turned into a standing ovation, lasting three or four minutes. Jagland’s face seemed to show an expression of relief. After the ceremony, in a news interview, he said that he understood the prolonged applause not only as powerful support for Liu Xiaobo but as an endorsement of the controversial decision that his five-person committee had made.

In the remainder of his speech Jagland stressed the close connections among human rights, democracy, and peace. He reviewed the four other occasions in Nobel history when a Peace Prize laureate was prevented from traveling to Oslo: in 1935, the Nazis held Carl von Ossietzky in prison; in 1975 Andrei Sakharov was not allowed to leave the USSR; in 1983, Lech Wałe˛sa feared he would be barred from reentering Poland if he went to Oslo; and in 1991, Aung Sang Suu Kyi was under house arrest in Burma. Even so, each of the latter three laureates was able to send a family member to collect the prize. Only Ossietzky and now Liu Xiaobo were prevented from sending a family member.

Jagland stressed that his committee had great respect for the Chinese nation, and observed that support of dissidents makes countries stronger, not weaker. The US had become a stronger nation because of the work of Martin Luther King Jr., another Nobel Peace laureate.

After Jagland’s speech the Norwegian actress Liv Ullman read the full text of the statement that Liu Xiaobo had prepared for his trial in Beijing in December 2009. The statement is called “I Have No Enemies,” and it was significant that Ullman read it in full because, at Liu’s 2009 trial, his own reading had been cut off after fourteen minutes. The presiding judge that day had interrupted him, declaring that the defendant could not be allowed to use more time than the prosecutor, who had summed up Liu’s crimes in only fourteen minutes. Ullman’s reading took about twenty-five minutes and was beautiful. She held the audience in immaculate silence when she read a passage in which Liu Xiaobo pays tribute to his wife Liu Xia:

I am serving my sentence in a tangible prison, while you wait in the intangible prison of the heart…. But my love is solid and sharp, capable of piercing through any obstacle. Even if I were crushed into powder, I would still use my ashes to embrace you.

The reading was followed by songs from a Norwegian children’s choir. Liu Xiaobo had requested, through his wife, who met him in prison on October 10 and was free to make phone calls until she was placed under house arrest on October 18, that children participate.

The climactic moment of the ceremony came when Jagland, unable to hand the Nobel diploma and medal to Liu Xiaobo, placed both upon the empty chair where he was supposed to have been sitting.

None of Liu Xiaobo’s friends living inside China whom he had wanted to invite to Oslo were able to witness these poignant moments (although some have been able to see it on the Web notwithstanding Chinese censorship). Attending in person, however, were about three dozen veterans of China’s human rights struggles who are now living in exile. Su Xiaokang—the writer of River Elegy, a television series that suggested that Communist Party rule is based in China’s “feudal” traditions and that had a tremendous impact in China in the summer of 1988—saluted Norway. “The big democracies—America, Britain, France, Germany—all know what democracy is but won’t stand up in public to Beijing’s contempt for human rights. It takes a little country to do a big thing.”

But many of the Chinese supporters of Liu still felt that well-intentioned Westerners have a long way to go before they really understand China’s politics. The Norwegian hosts repeatedly expressed a hope, for example, that Liu Xiaobo will soon be allowed to come to Oslo to collect his prize. Exiled Chinese who heard this kind-hearted wish knew, but did not say, how unrealistic it was. Even if Liu Xiaobo were to be released from prison, it is unimaginable that he would agree to leave China. If he left, the regime could bar him from reentry, as it has so many others, and his ability to influence life and ideas inside China would decline precipitously. Liu Xiaobo is smart enough not to let such a thing happen, so as long as the medal remains in Oslo, it is likely that he will be separated from it for a long time. (His wife could in the future try to collect it, but she, too, would have to calculate the risk of forced exile.)

Liu knows that the greatest potential for his ideas, and the most important effects of his Nobel Prize, will unfold inside China. China’s rulers have consistently denounced his Charter 08 as “un-Chinese,” even while they assiduously prevent its publication inside China, apparently from a fear that ordinary people, were they to read it, might not find it so un-Chinese. The Internet is porous, and the Nobel Prize will certainly make Chinese people curious to learn more about Liu Xiaobo.

In the twenty-four hours following the announcement of the prize on October 8, the Chinese-language website at Human Rights Watch, which was featuring Liu Xiaobo, got more hits from mainland China than it had gotten for about a year. Jimmy Lai, a refugee from Mao’s China who is now a media mogul in Hong Kong and Taiwan, and who flew to Oslo to support Liu Xiaobo, borrowed Mao’s famous line from 1949 that “the Chinese people have stood up.” They didn’t really stand up then, said Lai. “But now it could happen. Now people can see that ‘China’ in the twenty-first century can be something much bigger and better than the Communist Party.”

While others shared this kind of optimism, for many fear persisted as well: it is just too hard to say which side will win. At a happy gathering in the mid-afternoon of December 9, for example, Renée Xia, the overseas director of China Human Rights Defenders, received an urgent phone call from Beijing. Zhang Zuhua, who had been Liu Xiaobo’s main collaborator on Charter 08, had just been abducted by plainclothes police on a Beijing sidewalk.

When the police took him away they told his wife it would “probably be only two or three days,” but of course they both worried about the “probably.” He was brought in a car that had curtains on the windows to a Public Security guesthouse near Beijing. He doesn’t know where it was, except that he could “see mountains” outside. He was allowed to read but was held in a room that had no electric light, so when the sun went down reading stopped. He was allowed to go out into the sitting area with the police to watch television and chat and to stroll in the courtyard with the policemen.

This was only hours before the Nobel ceremony was to happen. It may have been that the authorities wanted to eliminate any possibility of a telephone hookup to Oslo. In any case they gave no reasons. Zhang was held until December 12, and then was allowed to go home. But when this happened to Liu Xiaobo two years earlier, the eventual sentence was eleven years. One never knows what will happen.

Hu Ping, editor of Beijing Spring in New York and a longtime friend of Liu Xiaobo’s, held little hope that China’s rulers would ever soften their position toward democracy and human rights. “As they see it,” Hu said,

the current strategy works. The formula “money + violence” works, and we stay on top. We know what the world means by human rights and democracy, but why should we do that? Aren’t we getting stronger and richer all the time? Twenty years ago the West wasn’t afraid of us, and now they have to be. Why should we change what works?

Hu recalled something that Liu Xiaobo had said to him many years ago. “We are lucky,” Hu reported Liu as saying, “to live in this time and this place—China. It may be difficult for us, but at least we do have a chance to make a very, very large difference. Most people in their lifetimes are not offered this kind of opportunity.”

—December 16, 2010

This Issue

January 13, 2011

-

1

English translations of both books are currently in preparation—by Stacy Mosher and Guo Jian for Mubei and by A.E. Clark for Ruyan, which will appear in March 2011 from Ragged Banner Press under the title Such Is This World@Sars.come. The translators of both books are in touch with the authors and are using authentic texts. ↩

-

2

See Ian Johnson’s interview with Yang Jisheng for the author’s own account of how he gained access to thousands of Communist Party archives and other documents, NYR Blog, December 20, 2010. ↩

-

3

Guan Wujun, “‘Tianjia’ weiwen bushi changjiu zhi ji” (Sky-High Stability Budgets Are Not a Long-Term Strategy), available at www.shekebao.com.cn/shekebao/node197/node206/userobject1ai2703.html. ↩