In The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, the first volume of Swedish writer Stieg Larsson’s trilogy Millennium, a disgraced journalist, Mikael Blomkvist, retires to the remote, fictional island village of Hedeby, three hours north of Stockholm, where an octogenarian industrialist, Henrik Vanger, has invited him to solve the mystery of his great-niece, who disappeared forty years before, aged sixteen. The key to the puzzle would appear to lie in five names and numbers that the girl, Harriet Vanger, wrote in her diary shortly before vanishing without trace:

Magda—32016

Sara—32109

R.J.—30112

R.L.—32027

Mari—32018

Since 32 and 30 are local area codes, it seems reasonable to suppose that these are phone numbers, yet the police found no correspondence between names and numbers. Perplexed, Blomkvist copies the list out and pins it up on the wall of the cabin where he is staying. After he has been on the island some months, his sixteen-year-old daughter turns up out of the blue. Blomkvist is divorced and rarely sees his daughter, who has hardly been mentioned to this point. She is heading for a Christian summer camp and though the island is very much out of the way it just happens to be on her way. Blomkvist isn’t happy about the girl’s religious inclinations and admits as the two say goodbye that he doesn’t believe in God; at which his daughter points out that nevertheless he reads the Bible: she “saw the quotes you had on the wall.” And she adds: “But why so gloomy and neurotic?”

Blomkvist doesn’t understand. The girl hurries off. Then it dawns on him: the first digit of the mysterious numbers indicates a book of the Bible, the second and third a chapter, the fourth and fifth a verse. Of course! Despite the fact that Blomkvist spends hours a day surfing the net on his computer, he now rushes off to find a Bible, strangely unaware that the holy book is freely available online in almost any language you care to mention. The digit 3 corresponds to Leviticus and he finds verses like:

If a woman approaches any beast and lies with it, you shall kill the woman and the beast; they shall be put to death, their blood is upon them.

And the daughter of any priest, if she profanes herself by playing the harlot, profanes her father; she shall be burned with fire.

Now at last it’s clear that the names Magda, Sara, etc. refer to the Jewish victims of a sexually perverted, anti-Semitic serial killer, something that would hardly surprise those reading the original Swedish and most European editions of the novel, which, in line with the author’s wishes, are more bluntly entitled Men Who Hate Women.

At this point, however, any half-awake reader is bound to object. First, since there are many more than ten books in the Bible, biblical references (book, chapter, verse) are never displayed with five-figure codes, so no one, however great their knowledge of the Bible, would assume them to be text references. Second, even imagining that the daughter made this connection, she would hardly be familiar with the content of these obscure verses from Leviticus; and even if she did make this connection and did recognize the verses, she would surely be concerned to inquire of her father why he was associating such disquieting material with specific girls’ names.

All this suggests that Larsson’s trilogy has not achieved its spectacular success thanks to the author’s impeccable skills as a detective story writer or any scrupulous attention to psychological realism. Loose ends and incongruities abound, lending the trilogy an endearingly amateurish feel, emphasized by a translation from the Swedish that, though for the most part fluent, occasionally treats us to decidedly muddled idiom (“He’s pulling the load of an ox and walking on eggshells”) or very curious register shifts, as for example when we have a young, uneducated punk Swede saying things like “you chaps” and “gad around.” From time to time, whether due to translation or otherwise, the imagery is plain comic; for example, Blomkvist remarks of the Leviticus murderer that “he was a cut and dried serial killer.”

Never mind. These failings pale to insignificance when one considers the sales figures. Published in 2005 in Sweden, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has now sold 50 million copies worldwide and was the first book to sell over a million on the Kindle. It has been on US best-seller lists for more than two years, and the other volumes of the trilogy show every sign of following suit. What is the attraction?

One character holds our attention throughout the trilogy and dominates discussion of the work: Lisbeth Salander. From the first pages, it’s evident that the journalist Mikael Blomkvist is an authorial alter ego. As Larsson once was, he is involved in running a left-wing magazine specializing in courageous investigative journalism; he is idealistic, committed, and of course in the novel he assumes the central, private detective’s role in a situation that sets him up to be a hero protecting vulnerable women from sadistic men. Not that Blomkvist is without his complications: he married and had a child with one woman while openly continuing an affair with another (his editorial partner Erika Berger), who in turn is happily married to a man who apparently has no problems with the arrangement. An experienced financial journalist, Blomkvist has the courage to take on big industry and as the story opens has just received a three-month prison sentence for libeling a major industrialist who deliberately fed him a false scoop in an attempt to destroy both him and his magazine.

Advertisement

When Blomkvist decides to take time away from journalism to tackle the mystery of Harriet Vanger, we feel sure that he will be the book’s main focus of interest. Then Lisbeth Salander, the girl with the dragon tattoo, becomes his researcher and rapidly takes over both the inquiry and the trilogy. All the real energy of the book will now come from her, to the point that it is only Blomkvist’s interest in Salander that keeps us interested in him.

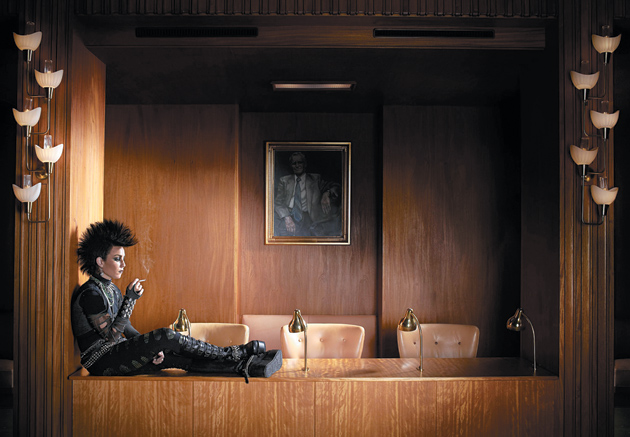

Lisbeth Salander is a pitifully thin young woman of twenty-four, not five feet tall, flat-chested, “a strange girl—fully grown but with an appearance that made her easily mistaken for a child.” When Blomkvist first meets her, he finds her “altogether odd”:

Long pauses in the middle of the conversation. Her apartment was messy, bordering on chaotic…. She had obviously spent half the night in a bar. She had love bites on her neck and she had clearly had company overnight. She had heaven knows how many tattoos and two piercings on her face and maybe in other places. She was weird.

How does Blomkvist know that Lisbeth maybe had piercings “in other places”? He doesn’t. But that is the kind of thing that Larsson’s alter ego likes to think. Blomkvist is, as we are frequently told, a ladies’ man.

Needless to say, a taciturn young woman of punk appearance flaunting aggressive, antisocial behavior must have had a traumatic childhood. So it is. For reasons unrevealed until the second part of the trilogy (though the reader has no difficulty guessing that male violence is involved), Lisbeth was locked in a psychiatric ward at age twelve and is still under the control of a legal guardian who disposes of her income. She is thus extremely vulnerable, a “perfect victim,” one character thinks of her. On the other hand she is also a “world class hacker,” a brilliant, self-taught mathematician, and “an information junkie with a delinquent child’s take on morals and ethics.”

Working freelance for a security firm that installs sophisticated alarm systems and carries out private investigations, Salander has a magical ability to get inside anyone’s computer at any time and find everything relevant there in just a few moments (something many of us can’t do on our own computers); she has a photographic memory, reads all she sees in a flash, and recalls it word for word; and, or so Blomkvist imagines, she also has “Asperger’s syndrome…. Or something like that. A talent for seeing patterns and understanding abstract reasoning where other people perceive only white noise.” Finally, when circumstances demand, Salander can be extremely violent, even sadistic. She is victim, superhero, and torturer. To emphasize this paradoxical, almost cartoonish aspect of her character, Larsson has the anorexic-looking girl wear T-shirts with aggressive slogans: I CAN BE A REGULAR BITCH, JUST TRY ME or KILL THEM ALL AND LET GOD SORT THEM OUT.

Salander’s dealings with her new guardian, Nils Erik Bjurman—which form the first novel’s main subplot—establish a pattern for the trilogy’s treatment of sexuality, which is arguably its central, if sometimes disguised, subject. Salander’s previous guardian, who generously gave her near-total freedom, has suffered a stroke and his substitute, Bjurman, a fifty-five-year-old lawyer, decides to take advantage of his new charge and satisfy a lust for domination: “[Salander] was the ideal plaything—grown-up, promiscuous, socially incompetent, and at his mercy…. She had no family, no friends: a true victim.”

Bjurman tells Salander that she can only have access to her income in return for sex. After forcing her to engage in oral sex in one encounter, at the next he handcuffs and brutally rapes her:

“So you don’t like anal sex,” he said.

Salander opened her mouth to scream. He grabbed her hair and stuffed the knickers in her mouth. She felt him putting something around her ankles, spread her legs apart and tie them so that she was lying there completely vulnerable…. Then she felt an excruciating pain as he forced something up her anus.

Salander, however, turns the tables. With access, through her work, to high-tech security equipment, she has placed a digital camera in her bag and pointed it at the bed where Bjurman rapes her. How easy, you would have thought, for her now to launch this on the Internet and destroy the man. But “Salander was not like any normal person,” Larsson tells us. She attends the next meeting with Bjurman as promised and when he tries to repeat the scene, she stuns him with a Taser, handcuffs him to the bed, and performs the same anal abuse on him; then she forces him to watch the video of the previous rape and spends a whole night tattooing on his chest in large letters “I AM A SADISTIC PIG, A PERVERT, AND A RAPIST.” From now on Bjurman must do exactly as she tells him, otherwise the video will be made public and he will be destroyed. “She had taken control,” thinks Bjurman in italics. “Impossible. He could do nothing to resist when Salander bent over and placed the anal plug between his buttocks. ‘So you’re a sadist,’ she said….”

Advertisement

There is an element of the graphic novel in all this, a feeling that we have stepped out of any feasible realism into a cartoon fantasy of ugly wish fulfillment. The same comic book tone returns whenever Salander takes retaliatory action:

Her teeth were bared like a beast of prey. Her eyes were glittering, black as coal. She moved with the lightning speed of a tarantula and seemed totally focused on her prey as she swung the club again….

Having investigated Blomkvist’s past for Henrik Vanger, the man who commissioned him to solve the mystery of the missing girl, Salander will eventually meet the journalist when he asks Vanger’s lawyer for a researcher to help him establish the identities of the victims in the strange list of biblical texts. Meanwhile, however, Salander’s unpleasant encounters with her guardian are intercut with a developing sexual adventure of Blomkvist’s. When the young Harriet Vanger disappeared forty years before, all the many members of the extended Vanger family had been on the island of Hedeby to attend a shareholder’s meeting of the company they jointly owned. Much aged, some of those members are still in residence and must of course be questioned as part of Blomkvist’s investigation.

Cecilia, a headmistress in her mid-fifties, abused in the past by her estranged husband, invites Blomkvist for coffee. When he turns up, she greets him in a bathrobe, is happy to talk about her need for an “occasional lover,” and props her bare foot on his knee. Very soon,

She sat astride him and kissed him on the mouth. Her hair was still wet and fragrant with shampoo. He fumbled with the buttons on her flannel shirt and pulled it down around her shoulders. She had no bra. She pressed against him when he kissed her breasts.

Their embraces become routine, but after Blomkvist is obliged to take time away from his investigation to serve his brief prison sentence, he learns on his return that Cecilia wants to end the affair because she is becoming too attached and losing control.

Shortly afterward, Lisbeth Salander is engaged to help Blomkvist with his research and comes to live with him in his cabin, sleeping in a spare room. After they have spent seven days gathering information about women raped, burned, bound, strangled, and mutilated over the last fifty years, Salander realizes that Blomkvist “had not once flirted with her.” For his part Blomkvist is concerned about being seen around with Salander because she looks “barely legal” and hence he might appear to be “a dirty old middle-aged man,” something that worries him greatly. Irritated because she knows the journalist likes women but has made no move on her, Salander goes to his bed and climbs in. Like Cecilia she sits on top. And she doesn’t mind that he has no condoms. What matters is that she has control. Again, like Cecilia, she prefers separate beds once the fun is over.

The reader is thus presented with quite an array of sexual behavior, all strictly divided into the grotesquely obscene and the charmingly promiscuous. On the one hand there are Bjurman’s anal sadism and the gruesome, sexually motivated murders, child abuse, and incest that lie at the heart of the investigation into Harriet’s disappearance (to which, in the later parts of the trilogy, will be added prostitution rackets and S&M pedophile porn). On the other hand, there are “transgressive” but harmless encounters between consenting individuals: Blomkvist with his married lover, Erika Berger (who, we hear, prefers sex with two men at a time), Blomkvist with Cecilia, Blomkvist with Salander, Salander with her lesbian lover, Mimmi (they play domination games), and so on. Notably, all sexual encounters in which men take the initiative are violent and pathological; all encounters in which women run the relationship (avoiding commitment) are okay. There is nothing in between and no space for the conventional, assertive male libido. One might say that the emphasized and elaborately fantasized ugliness of one kind of sex makes the softer variety the only one possible and permissible.

The Millenium trilogy offers much entertainment typical of genre fiction: the puzzle of the complex crime in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, the suspense of the police investigation in The Girl Who Played with Fire, the drama of the political thriller in The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest. None of this is remarkable. What is surprising is the novels’ energetic focus on ethical issues and in particular the question of retribution. Fear and courage, so often central to thrillers and suspense narratives, are hardly discussed or dramatized; nor does Larsson make more than token efforts to have us really worry for his characters. We feel he is going through the motions when he has Blomkvist with a noose around his neck at the end of part one, or when Salander is shot in the head and buried in a shallow grave at the end of part two. We know our heroes are in no real danger because Larsson is not interested in these predicaments and makes little effort to imagine them. They are comic strip material. His two main characters themselves seem aware of this and hence are quite fearless. Half choked, apparently about to die, Blomkvist has time to reflect of his torturer, who is explaining how his father abused him: “Good Lord, what a revoltingly sick family.”

What matters instead is the division of the world into good and evil, a division that begins with splitting sex into positive and negative experiences, then ripples out from that in fascinating ways. On the side of rape and abuse are Nazism and anti-Semitism (the Vanger family includes many Nazi sympathizers), every kind of large organization (which is always understood as conspiratorial and always at some point involved in preying on young women), government, the secret services, big business, fundamentalist religion, and so on.

Even families are potentially dangerous insofar as they impose a closed world in which abuse can take place, or even be taught: Martin Vanger, the missing Harriet’s brother, was initiated in sex crime by his father, who helped him to rape and strangle a girl when he was just sixteen. Of the hugely extended Vanger family we are repeatedly told that none of its members, however unhappily married, ever divorced, as if this were an indication of a deep malaise. Investigate sex abuse and you come across a sick family and a corrupt organization. Investigate a corrupt organization and invariably someone is involved in sex abuse. Every attempt by one person to control another is evil.

On the side of cheerful promiscuity is the free person, able to move in and out of relationships and maintain more than one in openness and honesty. Lending her apartment rent-free to her lover Mimmi, Salander says she would like to come around for sex from time to time, but that it is “not part of the contract”; Mimmi can always say no and still keep the apartment. “What Berger liked best about her relationship with Blomkvist,” we are told, “was the fact that he had no desire whatsoever to control her.” Reassuringly, he “had all manner of terminated relationships behind him, and he was still on friendly terms with most of the women involved.”

So concerned are the candid, free individuals when they hear of sexual exploitation or any abuse of power that they inevitably become involved in pursuing it. Indeed Blomkvist, Salander, and their author draw most of their energy and motivation from the abuses they hate, to the point that you can no more imagine them renouncing pursuit of a sex abuser than renouncing sex itself. So while the first book turns up a sexually perverted serial killer, the second, The Girl Who Played with Fire, starts with a freelance investigation into sex trafficking (bringing underage Eastern European girls into Sweden as prostitutes), revealing complicity in the highest places. “Girls—victims; boys—perpetrators…there is no other form of criminality in which the sex roles themselves are a precondition for the crime.” In this world male prostitutes do not exist.

But what power does the ordinary person have to right these wrongs? Blomkvist and his steady lover Berger use their magazine, Millennium, to draw attention to crime and invite the authorities to take action, often a frustrating strategy, particularly when it comes to sex trafficking, because “everybody likes a whore—prosecutors, judges, policemen, even an occasional member of parliament. Nobody was going to dig too deep to bring that business down.”

Salander, on the other hand, as the supreme victim (we are aghast when we discover the full list of what she has been through), is unimpressed by the “insufferable do-gooder” Blomkvist, who thinks he can “change everything with a book.” She takes the law into her own hands and has no qualms about using violence and inflicting pain. Blomkvist, speaking for the modern liberal conscience, can’t condone this; he is always ready to consider mitigating circumstances. “Martin didn’t have a chance,” he says of the serial killer who followed his father’s footsteps. Salander’s response is doggedly simplistic: “Martin had exactly the same opportunity as anyone else to strike back. He killed and raped because he liked doing it.” He deserves violent punishment.

The gratification that the trilogy offers comes when, mediated through Larsson’s and Blomkvist’s troubled but admiring contemplation, Salander exposes herself to every kind of risk in order to mete out retribution to monstrous criminals, a retribution all the more satisfying when, in fine Old Testament fashion, it resembles the crime: an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, an anal rape for an anal rape. The greatest monster of them all, it turns out, is Salander’s Russian father, who beat her mother savagely, was a key man in the Russian secret services and a sex and drug trafficker to boot. The moment when, still filthy with the soil that has been heaped on her, Salander drags herself and three bullet wounds from a shallow grave to take an axe to her perverted father’s head can serve as an image of the pervading spirit of the book.

However, Salander never actually kills. Not by herself. Once she has reduced a victim to total vulnerability, fastening his feet to the floor with a nail gun, for example, she will anonymously contact some rival criminal eager to finish the job. It might be hard for the reader, or more pertinently her creator, to love her and the violence she deals out if she became a killer. As it is, we are invited to admire her ingenuity and expertise.

Not all is lurid. Food is important. Shopping. Furniture. Domesticity. Larsson invites us to identify with his heroes by filling in the ordinary moments of their lives, the humdrum aloneness that makes colorful sexual encounters so desirable. A cookbook could be compiled from Blomkvist’s efforts in the kitchen in the first novel of the trilogy. Salander prefers to get herself pizza and Coke. Both of them are used to eating alone in front of a computer screen. As independent spirits, they prefer Apple to Microsoft. Both pay more attention to technical stats than nutritional value. Replacing her computer after an accident, Salander

set her sights on the best available alternative: the new Apple PowerBook G4/1.0 GHz in an aluminium case with a PowerPC 7451 processor with an AltiVec Velocity Engine, 960 MB Ram and a 60 GB hard drive. It had BlueTooth and built-in CD and DVD burners.

One is reminded of the frequently cited technical specs of guns in Mailer’s Why Are We in Vietnam? The computer is Salander’s weapon. Unlike firearms, however, this is a weapon every ordinary reader handles every day:

Best of all, it had the first 17-inch screen in the laptop world with NVIDIA graphics and a resolution of 1440 x 900 pixels, which shook the PC advocates and outranked everything else on the market.

It is through the computer screen that the free individual can hack into the evil world of the great corporation with its corrupt practices and pedophile porn rings and begin the duty or the fantasy of striking back. Not quite Alice in Through the Looking-Glass but not unrelated; when Salander goes online she is transformed, omnipotent.

Many novels have captured the global imagination by presenting modern man as in thrall to a vast international conspiracy; one thinks of Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum or Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. The hidden organization that conditions and controls us is the antithesis of individualism and its natural enemy, an evil extension of the potentially perilous family that wields such power over us from birth, or the traditional marriage that restricts our sexual encounters, or the incompetent if not nakedly evil state that tangles us in a web of bureaucracy and is always complicit with organized crime. From all these things, Salander shows us how to be free, with inspired use of our laptops.

It is the ingenuousness and sincerity of Larsson’s engagement with good and evil that give the trilogy its power to attract so many millions of people. There really is no suspicion in these books that his heroes’ obsessions might be morbid. Certainly the reader will not be invited to question his or her enjoyment in seeing sexual humiliation inflicted on evil rapists. That pleasure will not be spoiled. It’s not surprising, reading biographical notes, that as an adolescent Larsson witnessed a gang rape and despised himself for failing to intervene, or that in his twenties he spent time in Eritrea training guerrillas—women guerrillas, of course—and then much of his mature life investigating and denouncing neo-Nazis.

Indeed he was so active in these matters that he felt it wise not to make his address public, or even his relationship with Eva Gabrielsson, his partner of thirty years. The two didn’t marry, she has explained in an interview, because under Swedish law marriage would have required publication of their address. Nor did they have children. As a result, when Larsson died of a heart attack at fifty in 2004, shortly before the first part of the trilogy was published and without having made a will, his estate passed to his father and brother, to whom he was not particularly close, leaving Gabrielsson with none of the vast income that was about to accrue. A man with a better eye for plot, one feels, would not have allowed such a loose end to threaten his achievement; unless these are precisely the pitfalls of remaining a free individual outside any confining social system.

This Issue

June 9, 2011

Storm Over Syria

The Charms of Eleanor Roosevelt