Families, it sometimes seems, are just a vast web of potential embarrassments…interspersed, no doubt, with the occasional opportunity for pride.1 Honor and shame, as much as love or liking, are what bind us to our kith and kin. The teenager rolls her eyes as her mother gets up to dance at the wedding; grandparents flush when their friends ask about the grandson who just “came out” in Sunday school; a wife looks down disconsolately as her intoxicated husband rises to make the after-dinner speech. We can all evoke such moments.

As for the upside: remember Aunt Rose kvelling—that wonderful Yiddish word, derived from the German Quelle, a spring, which gives just the right sense of gushing with pleasure—over her nephew’s medical degree, or those “Proud Parents of an Honor Student” bumper stickers. You may not love or like, or even know, Mary-Jane, but her kinship, once avowed, can bring you a warm glow when she wins an Oscar. “She’s my cousin,” you say to anyone who will listen. (You may not reclaim her when the stories about her rehab turn up in the tabloids, but you feel a moment of panic when your coworkers gossip about her. Do they remember Oscar night?)

Still, in the United States, it’s easy to escape your wider family. Families have contracted; the claims of kin are increasingly optional. Ancestor hunting is one of the more harmless addictions enabled by the Internet, but many Americans still couldn’t give the maiden name of both their grandmothers. In much of the rest of the world—as for most of human history—the web of kinship is rather stickier. It doesn’t just tell you who shares your “blood”; it helps fix who you are and explain why you are the way you are.

In rural Africa, certainly, things are still pretty much as they used to be everywhere. People keep track of their significant relatives and ancestors, in accordance with local rules of kinship. In most African societies, the tracing is patrilineal, running, like surnames in England, through the paternal line. Of course, mostly the people who will listen to these family histories are already family, or contemplating marrying into it. For these stories to gain a wider audience, a relative would have to achieve something truly worth kvelling over.

The British documentary maker Peter Firstbrook stepped into one of these large patrilineal clans when he arrived in Kenya, in late November 2008, to scout materials for a film about the president-elect’s Kenyan background. As he got to know the relatives of the new leader of the free world, they told him who they were in the way that was most natural to them: by connecting themselves backward in time to their ancestors.

The Obamas are Luo, belonging to an ethnic group that is now centered in Nyanza, in Western Kenya, near the shores of Lake Victoria. In the Luo past, family history was oral history, but these days, the Obamas know, an important family should have its lineage recorded in print (as grand Europeans have studbooks like the Almanac de Gotha). So they were delighted when Firstbrook decided that the materials he was accumulating would make the most sense as a book. Which isn’t to say that his notions about family narrative were identical to theirs.

Many years ago, the Belgian anthropologist Johannes Fabian identified a tendency he called “the denial of coevalness.” “The history of our discipline,” he wrote, reveals the use of time for “distancing those who are observed from the Time of the observer.”2 But this isn’t just a professional deformation of anthropologists: presented with an African—and especially a rural African—setting, many in the West instinctively turn to thoughts of the ancient human past. Firstbrook is no exception here. He begins a timeline that appears toward the end of his book with this item:

2.4 million BC…. A manlike ape or hominid called Australopithecus africanus lives in East Africa

Is it fussy to observe that the Obamas have no special claim on A. africanus just because they happen to live on the continent where the species disappeared two million years ago? Although the book blessedly avoids extensive discussion of prehistory, it does insist on recounting—on the basis of academic historical and anthropological accounts—the migrations of the Nilotic ancestors of the modern Luo people. Firstbrook flies north from Kenya to Juba, in southern Sudan, in order to visit the vast swamp north of the Imatong Mountains called the Sudd. “Historians and anthropologists,” he tells us solemnly, “believe the southern part of the Sudd to be the ‘cradleland’ of Barack Obama’s ancestors.” As it turns out, though, they left in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. Imagine a book about Bill Clinton’s family that began with the migration of the Franks—apparently Clinton has Frankish ancestry—in the fourth century: “Historians believe the middle and lower Rhine valley to be the ‘cradleland’ of William Jefferson Clinton’s ancestors.”

Advertisement

Fortunately by the third chapter, we are in real family history, following the life of Opiyo, the President’s great-great-grandfather, who was born in the early 1830s in Kendu Bay, on the shores of Lake Victoria. Because Firstbrook was able to recover few specific details about him, he uses this chapter to introduce Luo traditions of birth, marriage, the building of family compounds, funerals, and so on. Opiyo is a name for a firstborn twin, and given that the Luo consider twins “a bad omen,” his life would have begun with the careful carrying out of rituals to keep away harm. Despite this, he “grew to be a strong and respected leader among the Luo of south Nyanza.”

Firstbrook calls this man Opiyo Obama in the chapter’s heading…which would probably have come as news to Opiyo. According to the Luo naming system, he should have been known by the combination of his own personal name and that of his father, which was Obong’o.3 In fact, the President inherited the name Obama because it was the personal name of Opiyo’s son. When the President’s grandfather took the name Onyango Obama, he was simply following Luo tradition. “Onyango” was his personal name, “Obama” was his father’s. It wasn’t the name of a family.

The breach of naming traditions came in the generation that followed, when Onyango’s son Barack took the name Obama. In the colonial period, the father’s second name came to be treated like an English surname. The idea of an Obama family, defined by a shared family name passing from father to son, is a colonial innovation. Of course, the President’s patrilineal kin thought of themselves as a family. That’s why they had all this genealogical information. But they wouldn’t have thought they were linked by a name.

Breaking with tradition, in any case, got to be something of a habit among the President’s immediate ancestors. Onyango Obama, born in 1895, chose in his twenties to call himself Hussein, taking the name when he adopted Islam. His family, who had become Seventh-Day Adventists, were scandalized, and some speculated that he chose Islam because he thought “Muslim ladies” were more submissive. Others noted that Islam, like Luo tradition, permitted polygyny. Whatever Oyango’s reasons, the man, Firstbrook observes, “seems to have taken satisfaction in being different.”

His failure to conform may have had something to do with his service, during World War I, in the King’s African Rifles (KAR) Carrier Corps, where casualties were astonishingly high. Of 165,000 African porters, more than 50,000 died, a death rate higher than the average on Europe’s bloody western front. When he returned, he declined to reside in his father’s compound, but settled instead into an army-issue tent. “People thought he was crazy,” Firstbrook observes. Onyango’s personal style, too, was different from the rest of the family. Unlike them, he ate at a wooden table with a knife and fork, wore European clothes, and was obsessive about cleanliness. He admired the British, Firstbrook says, “especially their discipline and organization,” and by the mid-1920s, he was making a very good living as a cook for British families in and around Nairobi.

It was his fourth wife, Habiba Akumu, who first bore him children, including, in 1936, Barack Obama père. But Onyango had a notoriously violent temper, which he took out on the women and children of his household, and they soon drifted apart. In 1941, he married again, to Sarah Ogwel, who, as “Mama Sarah,” has become something of a family spokesperson and matriarch. Theirs was the longest lasting of Onyango’s marriages. “The difference between Mama Sarah and these other women,” her brother explained, “was that Sarah would not talk back to him.”

That Onyango ended up living not in Kendu Bay but in a village some fifty kilometers away called K’ogelo was the result of one of his legendary displays of temper. In 1943, two years after returning from a second stint in the KAR, Onyango was back in Kendu Bay working for a local British colonial officer. The officer suggested that Onyango organize a soccer competition and supplied a trophy. Onyango thought that the cup should be named for him; the local chief did not. A furious exchange of insults ensued, in which the chief called Onyango a jadak (settler), on the grounds that his great-great-grandfather, Obong’o, had been born elsewhere. Onyango, with magnificent pique, set off with his family back to that ancestral village.

Advertisement

Unsuprisingly, neither Akumu nor Sarah was delighted at the prospect of being uprooted from the only home they had known. Unsurprisingly, he took no notice of them. The move created the division in the family between the Muslims in K’ogelo and the Seventh-Day Adventists in K’obama. The division persists to this day; the soccer trophy seems to have been lost.

Not long after they arrived in K’ogelo, Onyango and Akumu had their last row. She felt in fear of her life, and walked back to Kendu Bay, leaving her children behind, to be raised by Sarah. Despite the fact that Sarah had two sons of her own, Barack was the son whose education became the family’s priority. His father went to considerable expense to send him to the Maseno boarding school, then (as now) one of the best schools in the country. But Barack left Maseno before his final year, having run afoul of a harsh headmaster. Onyango proved even harsher: he beat the returning prodigal with a stick and sent him away. “I will see how you enjoy yourself, earning your own meals,” he said.

By the mid-1950s, Barack was working for the Kenya Railway in Nairobi. While visiting his relatives in K’obama, he reconnected with Kezia Nyandega, a young woman he had known as a child in primary school. She recalls the first time they danced together at a Christmas party in Kendu Bay in 1956: “I thought, ‘Ohhh, wow!’ He was so lovely with his dancing. So handsome and so smart.” The attraction was apparently mutual and she became the first of Barack Obama Sr.’s four wives.

Meanwhile, he was getting caught up in the whirlwind of independence activism. These were the years of Mau Mau and many Kenyans—Onyango among them—were subjected to the indignities of interrogation and detention. Barack, too, was arrested, at a meeting of a banned independence organization. He was released at the insistence of his white employer, who assured the police that Barack had nothing to do with Mau Mau. Oyango had declined to pay his son’s bail: he took Barack’s political activities to be yet another instance of his irresponsible ways.

Firstbrook describes clearly the wider historical background to the Obamas’ progress through twentieth-century Kenya. We see the arrival of British colonial rule in East Africa and the competition between British and German colonization efforts in East Africa, which World War I decided in Britain’s favor. We learn how the two world wars affected life in Kenya, uprooting men like Onyango Obama; we watch the emerging independence movement and the Mau Mau uprising, in which tens of thousands of Kenyan Africans, many of them children, were killed, as well as a relatively small number of European settlers.4 We see the coming of independence and the rising conflict between the leaders of the Kikuyu and Luo communities. Barack Sr. became a close friend of the leading Luo politician of the independence generation, Tom Mboya, and his destiny was tied, for the rest of his life, to the fate of the Luo political leadership.

In 1959, Tom Mboya announced the “Airlift Africa” program, with fund-raising assistance from African-American public figures such as Jackie Robinson, Harry Belafonte, and Sidney Poitier, as well as various white liberals. The aim was to allow future Kenyan leaders to study on American campuses. Obama, having left high school without doing his final exams, didn’t get one of these scholarships. But eventually he prepared for and took the exams, and, with the financial assistance of two American women who were living in Nairobi, he was able to study at the University of Hawaii, in Honolulu. Firstbrook adds, “The records of Barack’s move to the United States are incomplete, but it seems that he also received some funding from Jackie Robinson.”

In 1960, in his second year at the university, Barack met Ann Dunham, the daughter of a furniture salesman from Kansas who had lived in several American cities with his wife since World War II. The two young people began dating, and Barack evidently felt no need to mention his wife and two children back in Nairobi. Soon, Ann was pregnant, and—over Onyango’s long-distance objections—the two got married, with only her parents as witnesses. Six months later, she gave birth to her now-famous son.

Barack Obama Sr. graduated from the University of Hawaii in 1962 with a degree in economics, and took up the offer of graduate education at Harvard. Ann—who had dropped out early in their marriage—stayed in Honolulu and returned to college. In Cambridge, Barack was soon exploring new possibilities. As one of his Kenyan fellow graduate students put it: “The women liked this man.”

Of course, in the world from which he came, having a wife or two was not a reason to avoid other women. There is some uncertainty about whether Obama visited his American wife and child in Hawaii in the three years he was at Harvard: one of his friends from the period recalls him boasting about his son and visiting him “more than once.” In Dreams from My Father, his son remembers only one visit, years later, in 1971, when he was ten years old. In 1964, Ann Dunham filed for divorce. By then, Barack had taken up with Ruth Nidesand, a teacher of Lithuanian-Jewish ancestry who became his third wife. A year later, he gave up his doctoral studies and returned home.

The young Obama had left a colony. He returned to a country. Jomo Kenyatta was the president of independent Kenya, and Tom Mboya was minister of justice and constitutional affairs. Barack, who published a paper, “Problems Facing Our Socialism,” in 1965, focusing on the perpetuation of colonial-era inequality in the postcolonial nation, found a highly paid position in Kenya’s Central Bank.5 His very active social life included countless parties with some of the leading figures in the government, although, Firstbrook writes, he was keener on ordering rounds of drinks than paying for them.

Then, in 1969, Mboya was assassinated, and Nairobi exploded in ethnic rioting, amid suspicions that the killing was the work of Kenyatta and his Kikuyu supporters. Over the next six months, interethnic relations in Kenya deteriorated, culminating in an extraordinary speech by Kenyatta that referred to the Luo in his audience as “writhing little insects…who have dared to come here to speak dirty words.” There were more riots; police massacres brewed more enmity. And Obama suffered the fate of many Luo in the period. While Mboya had been alive and in power, he had had a protector. Now, he was going to have to fend for himself.

He did not have the habits or the temperament to succeed on his own. He was a party-loving, hard-drinking man—nicknamed “Mr. Double-Double” because he liked to order two double whiskies at once; his binges meant he didn’t always show up for work. He was a loud, frank critic of a government that had made it clear that it was not going to tolerate “dirty words.” And the first problem exacerbated the second, since he was especially prone to making verbal assaults on the government when he was in his cups.

In the last decade of his life, Barack Obama Sr. slid slowly into the abyss. He was fired from a series of jobs. He had, as Firstbrook puts it, “a reputation for having a massive ego and a big mouth, both of which grew alarmingly when he started drinking.” He was also, according to Ruth’s son Mark, abusive to his wife and children, and Ruth eventually left him, taking her sons with him.

For all that, in 1981, he married a young Luo woman—apparently the women still liked this man—and in the summer of 1982, Kezia, the last of his wives, gave birth to George, the last of his sons. A few months later, Obama was dead in a car accident. He had set off home at the wheel after an evening spent drinking in a downtown bar in Nairobi and driven off the road into a tree.

This being Kenya, there were suspicions among his circle of friends that he was yet another Luo big man assassinated by the government. But Barack had a history of driving drunk and getting into accidents. Mama Sarah told Firstbrook, “We think there was foul play there.” Charles Oluoch—President Obama’s cousin—offered one family theory: his uncle had been poisoned in the bar: “They put something in your drink and they know you will be driving. At a certain point, you will lose control. It will look as if it was an accident.” Firstbrook passes this on as a “very serious accusation,” and you can see why the Obamas want to believe it. It makes the stupidity of death in the last of a series of alcohol-fueled accidents easier to accept: it also suggests that Barack Obama Sr.—a drunk who had talked himself out of one job after another—was still important enough to be worth killing.

Learning what President Obama’s father was like hardly makes one feel that our president would have been better off if Barack Obama Sr. had stuck around. Indeed, the son’s isolation from his father and grandfather—and his immersion in his mother’s happier and much more helpful family—must be part of what explains the contrasts between his persona and theirs. He is inclined to caution and self-restraint; they tended to be impulsive. He is slow to anger; they ignited like flash paper. They were men who desired many women and honored none; the President’s marriage seems a model of love and respect. What the three generations of Obama men have in common is intelligence, charm, ambition, and pride. But no doubt his Dunham ancestors could lay claim to those traits, too.

So don’t turn to The Obamas for enlightenment about the hidden motives of presidential policy making. The appeal of this book is, rather, like that of those centuries-spanning sagas that James Michener used to publish. At its best, Firstbrook’s book uses the glamour of the Obama name to invite readers to learn about a not-atypical East African family, and so gain insights into Kenyan history. The mistake would be to regard this family history as a fount of insight into our Obama.

The epigraph to Firstbrook’s prologue is the Luo proverb “Wat en wat,” which means (so he tells us) “Kinship is kinship.” Actually, though, things aren’t that straightforward. One Obama tradition the President has continued is of the son whose father provided a superfluity of reasons for embarrassment. Meanwhile, back in Kendu Bay, the Obamas take pride in their far-off kinsman. Barack Sr.’s sister Hawa Auma—who makes perhaps two dollars a day selling charcoal—may not be rich in the things of this world, but she can kvell over the fact that she is the aunt of the most powerful man in the world.

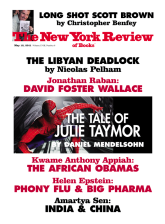

This Issue

May 12, 2011

-

1

Message to my own family: you are a splendid exception, of course. I am proud of every one of you. ↩

-

2

Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (Columbia University Press, 1983), p. 25. ↩

-

3

Firstbrook visited the grave of Opiyo’s son, whose headstone, which was added relatively recently, is reproduced in the book. There he is called “Obama K’Opiyo.” In his comment on the visit, Firstbrook appears to conflate the two men, since he refers to him both as the great-grandfather of the President and as having been born around 1830. But the family tree at the front of the book says it was great-great-grandfather Opiyo who was born around 1833. As a result of this confusion, when he takes up the life of Opiyo a few chapters later, a less than careful reader might lose track of the fact that it is the President’s great-great-grandfather that is under discussion. In other words, the man called, on the gravestone, Obama K’Opiyo is not the man Firstbrook calls Opiyo Obama, but his son. ↩

-

4

No one now believes the official British figures that 11,503 Kenyan Africans were killed; as Firstbrook writes, the death toll of thirty-two European settlers is widely accepted. Caroline Elkins in her controversial Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya (Henry Holt, 2005) estimates that more than a million Kenyans were detained and that a hundred thousand may have died. ↩

-

5

A more in-depth discussion of this work, and of this period in Barack Sr.’s life, can be found in Chapter 1 of David Remnick’s The Bridge: The Life and Rise of Barack Obama (Knopf, 2010). ↩